The Dictator’s Tomb

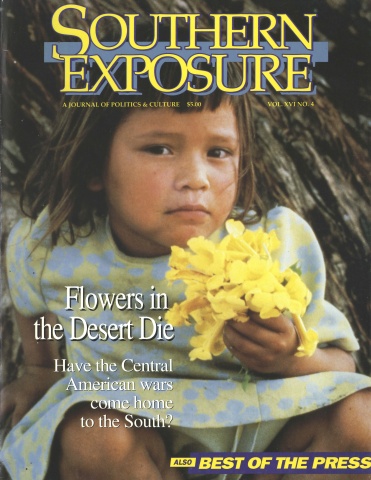

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 4, "Flowers in the Desert Die." Find more from that issue here.

In late 1985, the Nicaraguan newspaper Barricada sent writer Guillermo Cortes Dominguez to Miami to report on the community of contras and other Somocistas — the guards and officials of dictator Anastasio Somoza — who had fled to the United States when Somoza was overthrown in 1979. Miami is the center of the Nicaraguan exile community; an estimated 100,000 Nicaraguans live in the city. Most are refugees from a country devastated by war, but Miami also serves as the headquarters for the contras and relatives of Somoza eager to return to power. Cortes turned in a week-long series, beginning his tale at the tomb of Somoza. The excerpts below represent the first English translation of Cortes’ work.

Miami, Fla. — The king of the miasma was right there, under my feet, worm-eaten, inevitably decayed. The almighty god of Nicaragua’s darkness doesn’t rest in peace in this, the largest cemetery in Miami. He is simply dead.

The burial plot in Miami was already bought, but his family members did not decide until the last minute to bury him here; they hurriedly had a square, white mausoleum built, like some of those in Managua’s General Cemetery.

The remains of his blown-apart body were brought here from Paraguay and were carefully watched over in a mortuary called “The Gentlemen,” a name whose delicate irony seemed to take one final jab at the tyrant.

Svelte ex-soldiers, showing off their gala uniforms, silently stood guard at the entrance to the chapel. Somoza was dead and his family was afraid. The Nicaraguan guards let no stranger in.

Some Cubans own the funeral home, and the cemetery is located on 8th Street, in the anti-communist sector of Miami known as “Little Havana.” Several Cubans attended the wake, including various members of Assault Brigade 2506, humiliated at the Bay of Pigs, along with the owners of the anti-revolutionary radio station WQBA, “La Cubanisima,” the contras’ principal means of propaganda in this city.

Only a few months before the overthrow of the dictatorship, representatives from both the brigade and the radio station had been in Managua to express their support to the trapped tyrant.

Day of the Dead

Nothing suggests that the tomb might be his. It could only have occurred to my companion to bring me to this cemetery at night, and precisely on Halloween, the eve of El Dia de los Muertos — All Souls Day, or literally, the Day of the Dead.

Among the fenced-in plots, tombstones, images, shadows, crosses, and a timid moon veiled by black clouds, we quickly stole across the cemetery until we arrived trembling at his unmarked tomb. And he was frightening even in the grave. I foolishly thought he might arise from the dead.

We crossed the grass surrounding the mausoleum and descended to the crypt, nervously supporting our feet on those cold and eternal stairs that took us to the vault.

I don’t know if there was any light or if it was my sinister companion’s flashlight that permitted us to orient ourselves, now inside, alone with “the General.”

He lay to the left of the stairs, in an encrusted drawer in the wall. There he was, magnificently dead.

As if chased by his shadow, we ran, terrified, out of that cursed cemetery.

The Return

The wife of a former soldier told me that one of Somoza’s personal aides, Colonel Victoriano Lara, is buried in the white mausoleum, right beside the tyrant. Anastasio Somoza Portocarrero, the son of the dictator, commented that Lara and his father would be together “until we return” to power in Nicaragua. And he wasn’t kidding.

That is the golden dream of the Somocistas. “The Return” is a fixation, an obsession. Their parties, their gatherings, and even informal conversations are unavoidably charged with their nostalgia for power. They even invent pinata parties for the kids, but those serve as pretexts to get together, to see each other, and to chew the fat about their memories. The Return is more than an aim, more than a goal, it is almost a diseased sentiment.

Their conversations are always the same. They talk about what they were, about their privileges, their power, and they even brag morbidly about the tortures and assassinations that they committed. After a few drinks, they elaborate their ideas of what they’ll do to the Sandinistas when they return to Nicaragua. Although the top Sandinista leaders occupy a special place in their meditations, they basically think about killing everything that even “smells” Sandinista.

When they’re more “toasted,” they brag even more and imagine themselves victorious in combat, conquering city after city, the siege of Managua, and finally their glorious entrance to the capital. They dream of celebrating The Return at Los Ranchos Restaurant.

They also speak of revenge. A bloody orgy is anchored in their brains. I don’t know if they are aware of just how many Nicaraguans participated in the Revolution. Carrying out their desire for revenge, then, would mean assassinating hundreds of thousands of people.

The guards still salute each other militarily at their gatherings. They call each other Commandante. They raise their hands to their foreheads, accompanying the gesture by clicking their heels. If someone doesn’t show on time for an appointment, another will phone him up, saying: “Commandante, you’re wanted at Headquarters. Report immediately or you will be restricted for six months. Bring all the grenades — beers — that you can.”

The old bloody stories that the guards never get tired of repeating now mesh with the new “feats” recounted by the “freedom fighters” who occasionally come from Honduras to rest on Miami’s paradisiacal beaches. A sort of “vacation program” exists for “well-behaved guards,” coordinated in Tegucigalpa, so that there are seasons in which Miami Beach fills with Somocistas who, after “resting up,” return to their bases along the Honduran border with Nicaragua.

On July 17, 1979, the day the dictator and his closest aides arrived at Miami Airport, he told them that they would stay for a few weeks, six months at the most. That promise is still a bitter memory for ex-Colonel Luis Alberto Luna, the journalist’s terror, who had casually ordered the termination of the radio news program where I began my career as a reporter.

A Cadillac awaited the tyrant at the airport, while the rest of the guards and officials took a bus. “We cry a little,” Luna later confessed to a journalist from the Miami News. After several years of repairing radios, of trying unsuccessfully to sell real estate, and of working in a printing shop, Luna finally arrived at a brilliant conclusion: “I lost my paradise.”

Five-Star Service

The Return is like an illness manifested in multiple forms, as illustrated by the “prologue” of the menu at the exclusive Los Ranchos Restaurant, owned by Somoza’s nephew Luis: “Every aspect of our restaurant, from its ambience to its decor, steeps us in an atmosphere of nostalgia for our land “ Ministers, vice-ministers, and other high-ranking officials meet here to build “castles in the air.”

Behind Los Ranchos, located at 125 Southwest 107 Avenue in the Commercial Center of Sweetwater, there is another restaurant called “El Taquito,” for the “less important” soldiers. There they have hung up a map to follow the supposed military operations of the contras with arrows, colors, and indicators. According to those carefully marked movements, the Somocistas are on the edge of taking over Nicaragua.

With a great deal of reserve, not to mention fear, I accepted an invitation from a Nicaraguan woman residing in Miami to eat dinner at Los Ranchos, where I saw Guillermo Rivas Cuadra, an infamous Somocista judge; to my surprise, he was working as a cashier.

The place is excellent, first class. It is an international five-star restaurant and the service is enviable. The waiters are super-efficient, friendly, and at times bothersome, because they seem to scrutinize you constantly. If you’re going to light a cigarette, one of them appears like an arrow with his lighter lit before you can even begin to light it yourself.

The personnel is Somocista, many of them former guards, particularly the waiters. An unavoidable question is how these assassins have managed to refine their manners and be so attentive and helpful. It was difficult to eat meat without thinking of all the people they had butchered in Nicaragua.

Trash for Honduras

Both drug and arms traffic and personal ambitions divide Somocistas in Miami and Honduras. Corruption is so pervasive that nobody trusts anybody.

During these six and a half years, the corruption, intrigue, and crime that had reached the highest levels in Nicaragua under Somoza inevitably moved to Miami. The arms and drugs business, like the friction and open disputes that sometimes end in tragedy, are the order of the day.

They fight over the aid that the Reagan administration provides to the contras. The thirst for U.S. dollars, for power, are among their incurable evils.

Even the Somocista ex-colonels sarcastically admit that the majority of the funds and equipment destined for the contras in Honduras stays in Miami, filtered through an intricate web of banks, real estate offices, restaurants, supermarkets, and medical clinics. “We send the trash to Honduras,” commented one of them. Contra leaders like ex-colonel Enrique Bermudez and Adolfo Calero would surely like to know his name.

Perhaps such leaders are the ones diverting a great part of the funds to bank accounts in various North American cities; the disloyal ex-colonel must have been irritated because his share is proportionately insignificant. But if his bosses realized that he is stealing their money, it wouldn’t matter to him. He would be dead.

Phone Wars

When contra leaders first began arriving in Miami, the CIA gave them a secret telephone access code of 12 numbers to call people in Nicaragua who could give them daily information to use for propaganda. The agency’s director William Casey could not have imagined that the move would provoke a scandal involving millions of dollars.

The access code spread like a plague. Somocistas gave it out to friends and relatives, or simply sold it to the highest bidder. Thus began an entire business.

“Telephonism” gripped the Somocista exiles. A previously unknown passion was born and developed in a few days, and the deluge of calls congested international lines. The contras communicated day and night with Managua and other cities and incredibly, they would call China or Japan just to be able to use the “magic” number, even though they couldn’t understand the person speaking on the other end of the line.

The codes were changed weekly, but the new number would spread in a few hours. The contras and their friends reportedly ran up an unauthorized phone bill of $160 million.

The “telephone war” provoked a scandal. The CIA scolded the Somocistas and demanded complete discretion in their use of the card. Moreover, the number of authorized users was drastically reduced.

Gone But Not Forgotten

Outside of this communications fever, the Somocista exiles live their sleepy lives in apartment blocks and duplexes. Little by little, they continue to lose the powerful confidence they initially had of returning to Nicaragua “in six months,” as the tyrant told them on the day they arrived in Miami in 1979.

Those six months have already become six years. The stolen money has dried up. The honorable ministers, generals, and other officials have really had to work — even their wives, who care for children and old people. Others sell pork tamales, like the mother of Dinora Sampson, Somoza’s mistress.

The Return not only projects itself in their gatherings and dreams, but also in other things: the Mercedes Benzes of the “big shots” have been exchanged for less pretentious vehicles, because here they can’t afford the upkeep. But they haven’t lost the last license plates extended by Somoza, and they put them on the very front of their now modest cars to make them feel at home.

Gone is the enthusiasm produced by the installation of training camps in the Everglade swamps outside of Miami. Somocista practices there were carnivalesque. Guards and civilians arrived with tents and thermoses, but there was more drinking than military exercises. The show, organized chiefly by Cuban anti-communists, attracted many unwary people who dished out respectable sums of U.S. dollars for the cause of “liberty.”

But a little beyond this place, about 40 minutes from Miami, also within the Everglades, a comparable number of ex-Nicaraguan soldiers did train seriously. They were later shipped to Honduras.

So, after six and a half years, the helpless anguish of the Somocistas is giving way to a torturous resignation that only momentarily disappears with a vibrant speech from Reagan against the Sandinistas, but returns like a painful boomerang with the disastrous military defeats of the new Somocista army, the contras.

On the outside of the tyrant’s square, white mausoleum, on a small note hanging from a plastic flower, I read: “General, your beloved guard won’t forget you.”

The whole U.S.A. seems to be a mausoleum.

And Miami is like a gigantic tomb of Somoza.