A Death in the Family

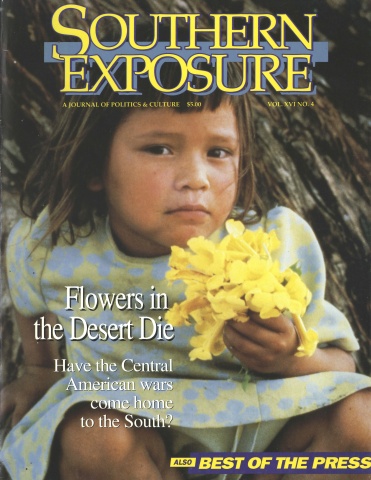

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 4, "Flowers in the Desert Die." Find more from that issue here.

Alabama has the highest infant death rate in the nation. In 1986, nearly 800 babies did not live to see their first birthday. Faced with those statistics, The Alabama Journal investigated the state’s infant-mortality crisis. More than 20 articles by Frank Bass, Emily Bentley, Susan Eggering, and Peggy Roberts appeared September 14-18, 1987. The project was a major undertaking for a small newspaper, requiring thousands of staff hours and a considerable financial commitment. In one story, Peggy Roberts examined how Medicaid woes contribute to the crisis.

Montgomery — Sixteen-year-old Terri’s voice shook as she described her ordeal since she discovered she was pregnant three months ago. “I’m overjoyed about it,” she said, obviously more sadly determined than happy. “Maybe it’ll change me. I was bad.”

A diminutive girl dressed in a Montgomery high school drill-team sweatshirt with her nickname on the back, Terri is facing more exasperating problems than the average pregnant teenager. When she applied for Medicaid to cover her prenatal care and delivery, Terri first was told she didn’t qualify. Although her mother, a single parent, has no work income, she wasn’t eligible because her younger sister collects Social Security benefits.

Even when she got Medicaid, she couldn’t find a doctor in Montgomery who would take her as a patient. With the number of delivering obstetricians in Alabama dwindling, it is getting tougher to find a doctor who will accept the minimal Medicaid payments. Medicaid in Alabama pays $450 to deliver a baby. That includes six prenatal visits and the doctor’s expenses in delivering the child. Doctors receive an average of $2,000 for a delivery paid for by the patient or by private insurance.

Terri was disgusted and confused over her predicament “I called every one of those doctors on the list they gave me, but nobody would take me,” she said, choking on her words. She doesn’t know if the obstetricians she called turned her down because she was too far along in her pregnancy or because there are too few obstetricians to care for the private patients willing to pay the entire fee.

She will continue to attend the Montgomery County Family Health Clinic, where she waits with 45 other women to see a volunteer doctor for a few moments. When Terri goes into labor, she’ll go to the emergency room and be delivered by an obstetrician who knows neither her nor her medical history.

Does Medicaid Aid?

Health experts are worried that Alabama’s Medicaid system is part of the reason infant mortality is so high. Each year, teenagers like Terri fail to receive proper prenatal care and lose their babies before the infants reach age one.

The Medicaid system is fast becoming one of the most hotly debated issues in the state. While experts can’t agree whether Medicaid reform is the answer to reducing the state’s high infant mortality rate, they do agree the system needs changing. ‘The Medicaid system isn’t helping many of those most in need,” said Dr. Earl Fox, the state’s health officer.

One option to expand Medicaid currently being considered in the legislature is participation in a federal program that would match three-to-one funds raised on the state level for the care of mothers and children. That suggestion, which has gained strong support among Alabama’s physicians, would allow pregnant women who earn more than the $1,416 annual limit allowed under the current Medicaid system to get medical benefits during their pregnancies and for the first year of the baby’s life.

For the present, however, to be eligible for Medicaid benefits in Alabama, a candidate must earn less than $118 a month, or 16 percent of the poverty level as set by the federal government. And even women who are eligible often fall through the cracks. Nineteen-year-old Debbie Edwards earned $75 a week as a waitress until she got too far along in her pregnancy to work. She had no health insurance, and although she took a leave of absence from her job, she isn’t sure the job will be open when she is ready to go back to work.

However, Debbie was ruled ineligible for Medicaid. She probably would have gotten Medicaid coverage if she’d simply said she wasn’t working. “You have to know how the system works to make it work for you,” remarked another woman at the Montgomery County clinic.

“I was four months along before I even knew I was pregnant,” Debbie said. She is receiving some prenatal care at the Montgomery County clinic, and when she is ready to have her baby, she’ll go to the emergency room. Then she plans to take on two jobs to pay the hospital bills.

The unemployed aren’t the only ones passed over when the Medicaid money is doled out. Faye and Randy Ford, a Chisolm couple, had their third baby in mid-December, just 10 months after their second child was born.

“Some people say she might have been premature because she was so soon after Taylor Michelle, but the doctor didn’t say for sure,” Faye explained. The new baby didn’t have extensive complications but was small and weak enough to require hospitalization for three weeks. When the Fords took their daughter home, they also took home a bill for $15,000.

Neither Randy’s job as a welder nor Faye’s job in a Montgomery factory offered health benefits, and Faye said they don’t earn enough to purchase a private insurance policy. “We had enough money saved to cover the cost of a regular delivery,” she said. Now they’re hoping to work out a monthly payment schedule that will allow them to pay their medical bills little by little, without devouring their total income. But it will take years.

A Silent Tragedy

Critics find little merit in the current system.

“It pays less than in any other state in the country,” said Dr. Robert Beshear, a Montgomery pediatrician who has been active in trying to draw lawmakers’ attention to the state’s infant mortality problem. “It actually penalizes a poor family in which the parents are making an effort but maybe only earning a minimum wage and receiving no health benefits,” he continued. “It seems to me that a system where a family who earns more than $118 per month can’t get assistance is tragic.”

Beshear is especially critical of state officials who haven’t made better mother and child health care a priority. “They have no long-term vision when they say we don’t need money for these programs,” he said. “It’s a great silent tragedy.”

Tags

Peggy Roberts

Alabama Journal (1987)