The Color of Money

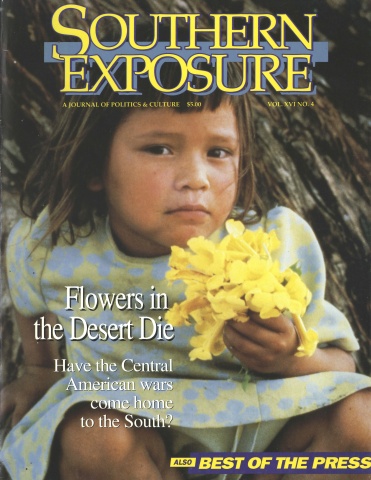

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 4, "Flowers in the Desert Die." Find more from that issue here.

Atlanta Journal-Constitution writer Bill Dedman showed that the city’s largest banks and savings and loan associations were not making home loans in predominantly black neighborhoods. The series, which appeared May 1-4, 1988, was one impetus for Georgia’s first county-sponsored fair-housing ordinance. In addition, Atlanta’s largest banks announced they would provide $65 million in low-interest loans for home purchases and home improvements, targeting Atlanta’s mostly black Southside. The city’s black ministers, deeming this insufficient, are campaigning to shift black deposits to black institutions.

Atlanta — Whites receive five times as many home loans from Atlanta’s banks as blacks of the same income — and that gap has been widening each year, an Atlanta Journal-Constitution study of $6.2 billion in lending shows. Race — not home value — consistently determines the lending patterns of metro Atlanta’s largest financial institutions.

Among stable neighborhoods of the same income, white neighborhoods always received the most bank loans per 1,000 single-family homes. Integrated neighborhoods always received fewer. Black neighborhoods — including the mayor’s — always received the fewest.

“The numbers you have are damning. Those numbers are mind-boggling,” said Frank Burke, chief executive officer of Bank South. “You can prove by the numbers that the Atlanta bankers are discriminating against the central city.”

As part of a five-month study, the Journal-Constitution used lenders’ reports to track home-purchase and home-improvement loans made by every bank and savings and loan association (S&L) in metro Atlanta from 1981 through 1986 — 100,000 loans. In the white areas, lenders made five times as many loans per 1,000 households as in black areas. With banks largely absent, home finance in metro Atlanta’s black areas has become the province of unregulated mortgage companies and finance companies, which commonly charge higher interest rates.

Among the other findings of the Journal-Constitution’s examination of home finance:

♦ Banks and S&Ls return an estimated nine cents of each dollar deposited by blacks in home loans to black neighborhoods. They return 15 cents of each dollar deposited by whites in home loans to white neighborhoods.

♦ The offices where Atlanta’s largest banking institutions accept home-loan applications are almost all located in predominantly white areas. Most S&Ls have no offices in black areas.

♦ Several banks have closed branches in areas that shifted from white to black. Some banks are open fewer hours in black areas than in white areas.

♦ According to information volunteered by two of the largest lenders, black applicants are rejected about four times as often as whites.

♦ A black-owned Atlanta bank, which makes home loans almost exclusively in black neighborhoods, has the lowest default rate on real-estate loans of any bank its size in the country.

The difference in bank lending to whites and blacks in metro Atlanta did not surprise some government observers. “I think it’s obvious that some areas of Atlanta have more trouble than others getting credit,” said Robert Warwick, vice president of the Federal Home Loan Bank of Atlanta, which regulates savings institutions.

“It’s institutional racism,” said city council president Marvin Arrington. “While we are patting each other on the back about being a great city and a city too busy to hate, they’re still redlining.” Redlining is an illegal practice of refusing to lend in certain neighborhoods on the basis of race, ethnic composition, or any standards other than credit-worthiness. The term comes from the practice of drawing a red line on a map around certain neighborhoods to designate them as off-limits.

Measuring Race

The impact of race on lending patterns was easier to measure in metro Atlanta than in some other cities, since housing patterns almost always follow racial lines here and since Atlanta has a substantial and identifiable black middle class. The study focused mainly on 64 middle-income neighborhoods: 39 white, 14 black, and 11 integrated. Middle income was defined as between $ 12,849 and $22,393 in 1979, the base year for the 1980 census. The study was controlled to ensure that neighborhoods were comparable in income and housing growth. All judgments about which data to include were made conservatively.

Even with these controls, distinct and growing differences appeared. Banks and S&Ls made 4.0 times as many loans per 1,000 single-family structures in white neighborhoods as in comparable black neighborhoods in 1984, 4.7 times as many in 1985, and 5.4 times in 1986.

Banking officials, while not questioning the accuracy of the figures, offered a variety of explanations. Some cited the aging of structures in the city. “Much of the housing in predominantly black areas is substandard, requiring rehabilitation to qualify for mortgage lending,” said Willis Johnson, spokesman for Trust Company Bank. “As a result, this cannot be handled through conventional mortgage lending channels.”

Officials at Atlanta’s black-owned bank disagreed. “I have difficulty believing that most of the housing in black neighborhoods is substandard,” said Ed Wood, executive vice president of Citizens Trust. “People who come from outside are amazed: ‘Black folks got these kinds of houses here?’”

Several banking officials said the differences might be caused by more home sales in white areas. The bankers were partly right. To check the demand, the newspaper analyzed real-estate records of all home sales in 1986 in 16 of the 64 middle-income neighborhoods. Homes did sell twice as often in white areas as in black areas. But of the homes that were sold, banks and S&Ls financed four times as many in the white areas as in the black areas. In white areas, banks and S&Ls made 35 percent of the home loans. In black areas, banks and S&Ls made nine percent.

Even lower-income white neighborhoods received more of their loans from banks than did upper-middle-income black neighborhoods. Lower-income white neighborhoods received 31 percent of their loans from banks and S&Ls. Upper-middle-income black neighborhoods received 17 percent.

In Cascade Heights, where Mayor Andrew Young and other prominent blacks live, 20 home-purchase loans were made in 1986. Of those, two were made by banks and S&Ls and two by mortgage companies owned by banks. The rest were made by unaffiliated mortgage companies.

If sales differences do not account for most of the lending pattern, banking officials said, then the number of applications probably would. While federal law does not require financial institutions to make public the number of applicants of each race, nor the number from each area, two of the 88 institutions in the study agreed to divulge application figures by race. These figures, from the largest savings institutions in Georgia, suggest blacks submitted proportionately fewer loan applications than whites, but they also show that black applicants for home-purchase loans are rejected four times as often as whites.

In 1987 Georgia Federal rejected 241 of 4,990 white applicants — 5 percent — but 51 of 238 black applicants — 21 percent. From 1985 through 1987, Fulton Federal Savings and Loan rejected 1,301 of 12,543 white applicants —10 percent — but 363 of 1,022 black applicants —36 percent.

It’s the Law

Equitable lending practices are required under the Community Reinvestment Act, which says banks and S&Ls have “continuing and affirmative obligations to help meet the credit needs of their local communities, including low- and moderate-income neighborhoods, consistent with safe and sound operation.” The law strives for a balance. Banks and S&Ls should protect the money of depositors and make a profit for shareholders, but it also says they should seek that profit in every neighborhood. Federal appeals courts have said banking is so “intimately connected with the public interest that the Congress may prohibit it altogether or prescribe conditions under which it may be carried on.”

Bankers said they bend over backward to obey the laws, and some said they are eager to make more money in black areas. “If I could make $10 million or $20 million in these loans, I’d make them,” said Thomas Boland, vice-chair of First Atlanta. “I don’t think a black borrower brings me any more risk per se.” But First Atlanta placed last in the Journal-Constitution’s ranking of 17 banks and S&Ls based on the percentage of home loans made to minority and lower-income neighborhoods. It placed 12th of 14 institutions based on lending to comparable middle-income black and white areas.

Only the city’s two black-owned financial institutions, Citizens Trust Bank and Mutual Federal Savings and Loan, made more home loans in black areas than white. These institutions, although small, appeared not to be suffering for lending mostly to blacks. Citizens Trust had a lower default rate on real-estate loans than the six largest banks in the city and the lowest of any bank its size in the country in 1986, according to the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, a government agency that produces reports for bank examiners. “I don’t see our default ratio being any higher because we’re working in the black community,” said Wood of Citizens Trust “I wouldn’t be in banking if I gave money away.”

On the other hand, several institutions that ranked poorly in the lending study capture the largest share of black customers, according to a 1986 study for the Journal-Constitution. First Atlanta, Trust Company, Citizens and Southern (C&S), and First American accounted for more than half the black customers.

In all, metro Atlanta’s blacks have an estimated $765 million deposited in financial institutions. That estimate is made by multiplying the number of nonwhite households in a 15-county metro area (204,802, according to the U.S. Census Bureau) by national black households’ average balance at financial institutions ($3,734, according to a 1984 Census Bureau survey).

The banks and S&Ls appear to invest little of black deposits in home loans to black neighborhoods. In middle-income black neighborhoods, each single-family home received an average of $339.27 in home-purchase loans from banks and S&Ls in 1986. Using the census estimate of $3,734 in deposits per black household, that’s an estimated 9.1 cents loaned on each deposited dollar.

In middle-income white neighborhoods surveyed, each single-family structure received an average of$2,432.82 in home-purchase loans. That’s an estimated 13.7 cents on the dollar in lending.

“We’re talking about disinvestment, capital flight from the Southside,” said Sherman Golden, assistant director of the Fulton County Department of Planning and Economic Development. “Southside residents put money in the bank and pay taxes, but their money is spent on the Northside.”

Hurting the Poor

Although the study focused on middle-income neighborhoods, the results concern groups working to solve Atlanta’s shortage of decent housing for the working class and the poor, regardless of race. “As long as they won’t lend in Cascade Heights, I don’t know how we’ll get them to lend in Cabbagetown or Ormewood Park or Pittsburgh or South Atlanta,” said Lynn Brazen, a director of the Georgia Housing Coalition. “We’re not asking the banks to do anything that’s not banking. We just want them to make money on the Southside, too,” Brazen said.

“It takes money to make money. The problem we have in the black community is there is no base with which to make money,” said the Reverend Craig Taylor, a white Methodist minister and Southside housing developer.

Neighborhoods say they need investment by financial institutions more than ever because federal housing aid is rapidly dwindling — from $33 billion in 1980 to less than $8 billion in 1987, according to the National Association of Realtors. Atlanta’s share of federal housing and community development money dropped from $8 million in 1983 to $4 million last year. The city earmarked half of that money for its tourist-entertainment complex, Underground Atlanta.

Without equal access to credit, community leaders say they watch their neighborhoods slide. When people cannot borrow money to buy or fix up houses, property values decline. Real-estate agents direct their best prospects elsewhere. Appraisers hedge their bets by undervaluing property. Businesses close. Home owners sell to speculators.

Redlining and disinvestment were hot issues in the mid-1970s, when Congress approved disclosure laws and the Community Reinvestment Act. A decade later, activists claim red lines are being redrawn, and Congress is considering legislation to enhance enforcement of the law. “Let’s face it: redlining hasn’t disappeared,” said Senator William Proxmire (D-Wisconsin), chairman of the Senate Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee. “Neighborhoods are still starving for credit.”

Tags

Bill Dedman

Atlanta Journal-Constitution (1988)