The Big Thirst

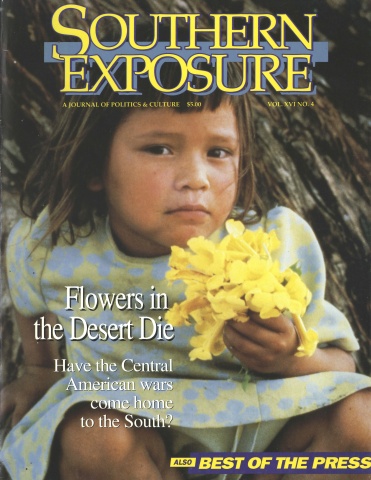

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 4, "Flowers in the Desert Die." Find more from that issue here.

For its six-part series on water issues, the El Paso Herald-Post conducted research and interviews in Texas, New Mexico, and Chihuahua, Mexico. “The Big Thirst” appeared April 18-23, 1988.

El Paso — A devastating man-made drought awaits El Paso’s entry into the 21st century. Unless more water is found, the drought will occur with the depletion of the city’s main source of fresh water by 2032 — or sooner.

The fear of a waterless future already embroils El Paso and New Mexico in a desperate, decade-old water war, and there’s no retreat or victory in sight for either side. In addition, a hidden battle for water under the arid Southwestern desert — documented and encouraged by the U.S. State Department — rages between El Paso and Juarez, Mexico. Both cities are pumping their main water supplies out of the same underground source.

The deep Hueco Bolson, situated between the Franklin and Hueco mountains, was hailed as a 200-year water supply 30 years ago. But it may not last another 30 years at the present rate of furious pumping by El Paso and Juarez, some experts say. “Right now, it’s a battle of turbine pumps,” says Albert Utton, a law professor at the University of New Mexico and editor of the Natural Resources Journal.

In Juarez, children die of dehydration each summer. It is a tragedy that is accepted as routine in areas where minimal needs for sanitary drinking water and sanitary sewer systems surge far ahead of the ability of the Mexican government to meet the needs. “Up until 1986, diseases due to dehydration and sanitation problems were the number one cause of pediatric and adult deaths,” says Dr. Emmanuel Apodaca, a physician with the Pan American Health Organization.

In El Paso, water consumption is about 190 gallons a person daily. That’s four times more than the per-person amount for Juarez, and despite looming dramatic conservation efforts in El Paso, the gap is expected to widen.

However, disease and the deterioration of El Paso’s quality of life are not deflected by international or municipal boundaries, say state and local health officials, who point out that epidemics result from polluted drinking water sources and supplies. The threat to health clearly exists among the swelling number of poor people who live just beyond the El Paso city limits.

Water Wars

“Whiskey’s fer drinkin’ — water’s fer fightin’.” So goes an old saying that over-romanticizes the bitter water feuds of the Old West. One feud led to the unsolved murder a hundred years ago of the harmless hermit Francois Jean Rochas, who homesteaded beneath the wild and rocky crags of Dog Canyon, 80 miles north of El Paso. The little Frenchman sparingly watered his cattle and small orchards from a tiny stream that still trickles down the canyon. Rochas’ envious neighbor was the powerful rancher and future New Mexico political giant Oliver Lee. Law officers never solved the Rochas murder; Lee eventually got his water.

Water wars escalated in the 20th century, and like armed conflicts, they produce not only casualties but also a variety of allies and activists. In this generation’s water war, El Paso is fighting New Mexico. Mexico opposes the United States. U.S. farmers are fighting urban encroachment. Health officials oppose industrialists. Opponents of growth are fighting promoters of growth. Environmentalists fight regulations they consider to be lenient, while developers fight the same regulations as too rigid.

Former El Paso Mayor Fred Hervey, credited with creating in 1952 the Public Service Board that oversees the water supply, thinks the crisis centers on quality and not quantity. “There’s plenty of different kinds of water underground. It’s enough to last 200 or 300 years. But it depends on how you treat it,” Hervey says.

If El Paso loses the fight for New Mexico water, the city may be forced to begin expensive desalting of poorer-quality ground water. That would mean the next generation of El Pasoans will pay water bills at least 10 times higher than today’s bills. Losing the fight would also drastically change the way El Pasoans live.

The Public Service Board already is preparing for that possibility, says board member Marshall St. John. “You’ll see very strict water-conservation regulations and penalties for violating those rules,” he predicts. “You will also see laws that require desert landscaping everywhere in town to cut down on water use. It will be drastic.”

That is just the beginning. Economists and political scientists say that although the board boasts of providing water to El Pasoans at a “cheap” rate, the rate is a false one. “The next generation will have to pay much higher water bills to make up for the ‘cheap’ rates the board provides today to make the city attractive to growth and development,” says Dr. Helen Ingram, a University of Arizona water politics expert. “It’s a vicious circle: populations are doubling and tripling. There is accommodation for growth and development. Demands for water double and triple, and then it starts all over again.”

Along with numerous other experts, Ingram testified during recent hearings in New Mexico against the Public Service Board’s applications to drill 287 wells across the state line. The board’s main water expert, Dr. Lee Wilson of Santa Fe, New Mexico, agreed with New Mexico’s experts about the predicted demise of the Hueco Bolson in 2032. Wilson’s research about groundwater pumping by El Paso and Juarez was presented to justify El Paso’s need for New Mexico’s groundwater.

Wilson says the pumping of the Hueco could be occurring up to 50 times faster than the bolson can be refilled. The Hueco is refilled by nature and with treated sewage water from the board’s state-of-the-art plant in northeast El Paso. “So, it becomes real obvious what is going to happen,” Wilson says. “You’re going to run out of water.”

Actually, the major target of El Paso’s continuing court duel with New Mexico isn’t the Hueco Bolson but rather the untapped Mesilla Bolson, which runs north-south from New Mexico into Mexico on the west side of the Franklin Mountains. Various U.S. water experts predict Mexico will beat El Paso and New Mexico to heavy pumping of the bolson.

Law professor Utton and others warn of “disastrous” consequences of two situations: runaway groundwater pumping of the Mesilla and the lack of groundwater treaties between the United States and Mexico. “El Paso’s water needs are accelerating, and Juarez needs more and more, and they need it now,” says Professor Ryan Barilleaux, a former University of Texas-El Paso political scientist.

“They [Mexico] will soon begin drilling in the Mesilla Bolson. It’s going to suck it out from under New Mexico real fast,” Barilleaux says. “The same thing is going to happen in the Hueco Bolson. So in a few years, El Paso is going to cease to exist if it doesn’t find a way to get some more water. It’s not going to be easy. It’s not like things are going to get better all of a sudden.”

Tags

Peter Brock

El Paso Herald-Post (1988)