This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 3, "Mint Juleps, Wisteria, and Queers." Find more from that issue here.

Here, in a nutshell, is what the federal government plans to do with the plutonium waste left over from its nuclear bomb factories in South Carolina and Tennessee:

First, put the waste in plastic bags. Like garbage bags. Then twist the bags shut. Next, put the bags in 55-gallon steel drums, put the drums in newly-designed casks, load the casks onto tractor trailers, and truck the casks 2,000 miles across eight Southern states. No guards, no special routes. Basically stick to the interstate highways, drive the stuff right past Atlanta and Memphis, Nashville and Birmingham, Dallas and Fort Worth. Drive it all the way to the salt beds of New Mexico. And then bury it.

That’s the plan. Thousands of barrels filled with plutonium-contaminated waste will soon be trucked thousands of miles across the South each year, if the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) succeeds in opening the nation’s first underground nuclear waste dump near Carlsbad Caverns National Park in New Mexico.

DOE officials say the nuclear shipments could start before the end of the year if the military salt mine, known as the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP), opens on schedule this fall.

Although citizens have had little say in the plan, the proposed defense shipments have already come under fire from Southerners who don’t think much of the idea of holding a 2,000-mile funeral procession for nuclear wastes destined for burial in a New Mexico graveyard.

Critics — including noted scientists, grassroots activists, and elected officials — say they fear a major disaster in the making. They say the DOE casks are untested and unsafe, state and local officials are unprepared for nuclear accidents along major Southern highways, and the WIPP site itself is already leaking.

“Just because it’s convenient for the nuclear industry to release radioactivity to the environment doesn’t mean we have to put up with this,” said Dr. Jack Neff, professor emeritus of molecular biology at Vanderbilt University. “I think you have to be terribly conservative in medicine and in protecting ourselves and the whole human gene pool. If they can’t do it without increasing radiation exposure, then they oughtn’t to do it.”

Go West, Old Waste

The opening of WIPP will launch the biggest wave of nuclear waste shipments in U.S. history. According to DOE estimates, at least 4,533 trucks carrying almost 200,000 barrels of nuclear waste will traverse the South by the year 2013.

Aboard those trucks will be discarded machinery, tools, rags, paper, clothes, gloves, sheet metal, glass, and dried sludge — the radioactive byproducts of nuclear weapons production. Such wastes are called “transuranic” (TRU) because they contain plutonium or other radioactive elements heavier than uranium. Most TRU wastes emit relatively low levels of radiation, but some remain extremely dangerous for as long as 240,000 years. If inhaled, ingested, or absorbed into the body through an open wound, they can cause cancer, birth defects, permanent genetic damage, and even death.

In the South, most of the waste will come from nuclear bomb factories and waste recycling centers at Oak Ridge, Tennessee and Savannah River, South Carolina. From Tennessee, the waste will most likely follow I-40 west through Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. From South Carolina it will probably follow I-20 through Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas.

Jim Tollison, the DOE manager overseeing the TRUPACT casks being designed to ship the military waste, insists that radiation from the shipments poses no health threat to the public — assuming, that is, that the casks don’t leak.

“Assuming no leaks, along the route with the hottest [most radioactive] shipments, the dose would be inconsequential to any member of the public,” Tollison said. “If you would hug a drum for 15 minutes, the dose you’d get would be one chest X-ray. You can’t even get that dose as this thing drives by, or even if you walked around it. The dose is very minimal, not even worth mentioning. The TRUPACT doesn’t even contain shielding. Workers can just walk up and carry these barrels.”

Still, accidents do happen — and as the number of nuclear shipments increases over the years, so will the chances of a major mishap. DOE officials say they expect 25 accidents in the next 25 years, but they insist that none of the accidents will cause “significant” radiation to leak from the TRUPACT casks.

“We do not expect any significant release of radioactive materials from transportation during the 25-year lifetime of WIPP,” Tollison said. “We do not expect, statistically, in that time, an accident severe enough to breach the package.” Although there will be accidents, he added, none “would require extensive cleanup.”

When accidents do occur, then, the safety of the public and the environment will depend on the safety of the TRUPACT casks. If the casks break, or leak, or explode, millions of citizens in large Southern cities could be exposed to potentially lethal radiation. “The hazard of this stuff is plutonium,” said Dr. Marvin Resnikoff, a physicist with the New York-based Radioactive Waste Campaign. “If there’s a fire or other accident, you don’t need much plutonium to get out to have a major catastrophe.”

Dr. Neff agreed. “My point of view is very simple. There is no dose of ionizing radiation that is ‘safe.’ Any dose can cause genetic damage in future generations, or cancers in present generations.”

Neff added that DOE standards only set “maximum permissible radiation doses. That doesn’t say they’re safe. That says, ‘This is an arbitrary limit we set up.’ Even with biological repair mechanisms, every bit of ionizing radiation has the potential to do damage.”

How Safe Is Safe?

So how safe are the casks? The truth is, no one knows for sure. Unlike containers used to transport irradiated fuel from commercial nuclear reactors, DOE containers for defense waste are not usually subject to approval by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC). Instead, the DOE is generally allowed to establish its own standards and certify its own casks.

Nevertheless, energy officials agreed to submit the casks for NRC approval last year after angry citizens wrote scores of letters protesting the lack of oversight. “I believe the DOE threw up its hands and agreed to NRC licensing when Southerners got involved,” said Janet Hoyle, director of the Blue Ridge Environmental Defense League in North Carolina.

Generally, the standards DOE had set for itself have proved to be considerably lower than the safety levels demanded by the NRC — and the regulatory agency hasn’t exactly established a reputation as a particularly tough watch dog. One study done for the state of Nebraska, for example, found at least 10 instances where spent fuel casks self-certified by the DOE were unable to pass NRC muster. Reportedly, the energy department continued to use some of those casks after the NRC refused to certify them.

In fact, the first design for the TRUPACT cask had two major flaws that made NRC approval unlikely. First, it contained only one layer of protective shielding instead of two. Second, it contained outlets to permit continuous venting of potentially explosive gases.

“So what did DOE do?” asked Caroline Petti, a Washington lobbyist for the New Mexico-based Southwest Research and Information Center. “Did they try to upgrade the design of the cask? No. They tried instead to get the standards lowered. DOE petitioned the Department of Transportation (DOT) to modify its regulations to permit NRC certification of the TRUPACT design. Fortunately, public outrage was sufficient to convince DOT to reject DOE’s petition for the time being.”

To their credit, Petti said, DOE officials agreed to redesign the TRUPACT container to meet NRC standards, eliminating the valves and vents included in the original design. “The cask will be certified by the NRC or it won’t be used,” emphasized DOE spokesman Dave Jackson.

Despite such assurances, DOE officials don’t deny that they would have preferred lowering the standards rather than upgrading the cask’s safety. “We had a very good design before, but it didn’t meet regulations,” said Tollison. “We could change the design or change the regulations. We changed the design because we didn’t have time to change the regulations.”

Test to the Max

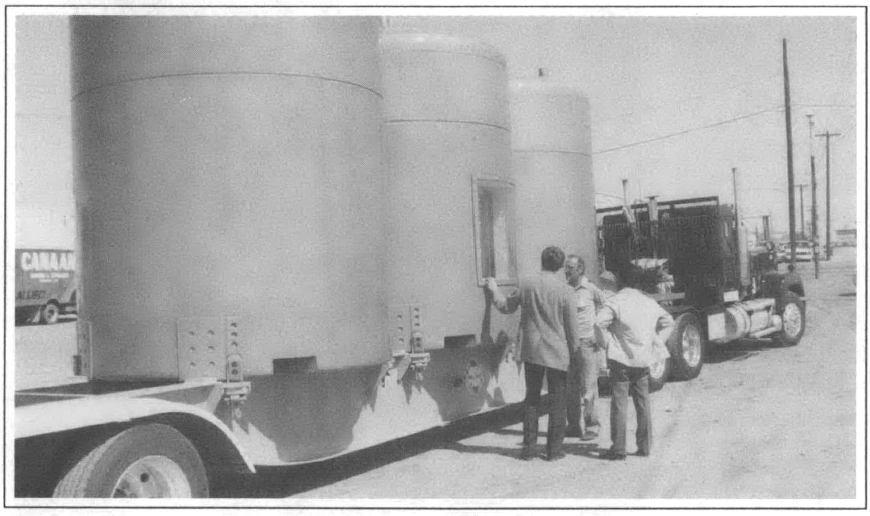

The new cask, known as TRUPACT-2, is 10 feet tall and will weigh 17,000 pounds when loaded with 14 drums full of waste. NRC certification may once again be hard to obtain, however, if initial tests are any indication. Designers have given the new cask a second layer of shielding required by the NRC and have removed outlets that would have vented radioactive gas into the atmosphere. Without the vents, however, those gases threaten to build up inside the cask and explode.

According to Melinda Kassen of the Environmental Defense Fund in Colorado, the redesigned cask has also developed faulty O-ring seals similar to those that destroyed the space shuttle Challenger in 1986. “The first set of O-rings on TRUPACT-2 were not sealing at very low temperatures,” Kassen said.

Tollison, who worked on the NASA Apollo program before joining the energy department staff, said the cask design is being corrected. “We tested the O-rings in the seals on the TRUPACT cask at low temperatures, and we changed the O-ring material to butyl rubber to maintain a leak-tight seal to minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit, which is what the regulations require.”

DOE spokesman Jackson said that until the tests are over, “There simply is no data that there are, or are not, problems with the new O-rings at low temperatures.

“If we find a problem, we will find a solution for it. We have to, or the damn thing won’t be certified.”

Leon Lowery doesn’t believe such assurances. A Tennessee environmentalist, Lowery has been working to strengthen laws governing nuclear waste transportation. “Since the TRUPACT-2 design isn’t totally finalized yet, and testing is not complete, I don’t see how anyone can express confidence in them,” he said. “It’s impossible to have confidence in a cask unless you have confidence in the process by which it was designed, built, and tested. The TRUPACT-2 process has been so haphazard, and so pushed by schedule, that you can’t have any confidence in it.”

Part of the problem, scientists say, is that NRC tests don’t actually simulate true-to-life accident conditions. Dr. Neff, the Vanderbilt biologist, said government tests only expose the casks to temperatures of 1,475 degrees Fahrenheit. Propane and diesel fuel (which the casks may actually encounter on the highway) burn at temperatures approaching 3,000 degrees.

“Having met up with these DOE guys, they’re about as tunnel-visioned and hard-headed as I’ve ever seen,” Neff said. “They are not paying sufficient attention to the safety of the casks. They don’t consider that any accident that they could imagine would result in the loss of damaging amounts of radioactive material to the environment.

Neff maintains that the DOE “ought to test these casks to the limit, to the worst possible accidents. This has not been done. Don’t use an arbitrary limit — burn it with diesel fuel.”

Asked about Neff’s “test-to-the-max” proposal, Tollison said the energy department will do only the testing required by law. “We are going to meet the federal regulations,” he said. “That’s what we’re required to do, and that’s what we’re going to do. Those regulations have stood the test of time, and if they change, we’re going to adjust to meet them.”

Coming, Ready or Not

Questions about the safety of the casks aren’t the only ones that remain unanswered. Environmentalists are also concerned about whether state and local governments are prepared for the possibility of accidents involving trucks loaded with radioactive military wastes.

Again, the DOE maintains that all is well. According to Tollison, the energy department will offer emergency training to every state the waste will pass through. “Training will include radiation protection and measurement,” he said. “Save lives first.”

A few months before shipments were scheduled to begin, however, most Southern officials still didn’t know when, where, or how much waste would be shipped through their states. Auburn Mitchell of the Texas Nuclear Waste Programs Office said state agencies were still waiting to be briefed by the DOE in August. “They’re talking about commencing shipments next year,” he said.

“It’s something we want to get more specific information on. We’re looking forward to the briefing to get more specific information on quantities, routes, et cetera.”

Petti, of Southwest Research, said previous accidents involving hazardous wastes have shown that state and local emergency response teams are often ill-equipped, disorganized, and inadequately trained to protect the public. She also said the DOE has done very little to train or equip officials in any states along WIPP shipping routes.

Many Southerners also say the DOE is not providing enough training. In fact, in many states the department has scheduled only one training session for emergency response teams — hardly enough, residents say, to teach local fire fighters and police officers how to respond to nuclear waste accidents.

“We’re being the pushover of the Western world on radioactive and hazardous waste,” said Bob Guild, a lawyer who works on nuclear waste issues in Columbia, South Carolina. “We need to stiffen the backbone of some of these elected officials.”

Tim Johnson of the Campaign for a Prosperous Georgia lives near a major WIPP transportation route. He questioned the safety of transporting any nuclear waste by truck. “They’ll be going through heavily populated areas on their way to less-populated areas. It doesn’t make sense to ship waste anywhere, especially through heavily populated places like Atlanta.”

DOE records show that department trucks have been involved in a total of 173 accidents since 1975, 72 of them in the South. According to Deadly Defense, a citizen’s guide to military waste landfills published by the Radioactive Waste Campaign, all of the accidents were run-of-the-mill — tired drivers, speeding, snow and ice, and deer on the highway at night. In some cases, the trucks lacked snow tires under winter driving conditions.

There are no records of any accidents involving radiation leaks. According to DOE spokesman Dave Jackson, “There has never been an accident involving the transport of radioactive materials in which anyone has been harmed by the content. Ever. And I can prove it.”

Melinda Kassen of the Environmental Defense Fund said the fact that there hasn’t been a serious accident yet doesn’t mean there won’t be one in the future. “We feel the DOE is sitting where NASA was in December 1985. ‘Never had an accident.’ Bragging on it. You know what happened.”

The End of the Road

As if transporting radioactive wastes 2,000 miles across country weren’t dangerous enough, the safety of the WIPP site itself has been called into question. A National Academy of Sciences panel recently concluded that the DOE should conduct further tests before dumping any waste in New Mexico. The panel also criticized the government for failing to thoroughly study problems at the site.

WIPP consists of an enormous cavern dug into salt deposits 2,150 feet beneath the desert and big enough to hold 1.1 million barrels of waste. The idea was that the radioactive military wastes would slumber in the salt beds for tens of thousands of years, secure and dry beneath their protective geological blanket. The salt would eventually corrode the barrels, but it would also contain the waste.

In January, however, a group of 11 independent scientists from New Mexico reported that water from cavern walls and a ventilation shaft is leaking into the cavern and could effectively render the waste dump useless. The highly corrosive brine could react with the barrels, the scientists said, allowing the wastes to leak into the Pecos River or other major water supplies. According to DOE documents obtained by the scientists, water is leaking into the cavern at 1.5 gallons a minute, enough to fill it in the 25-year life of the site. Engineers have so far been unable to stop the leaks.

DOE officials say the leaks should not delay dumping at the site. They call WIPP an “experiment” and promise to remove all the waste from the cavern if anything goes wrong in the first five years, even though they have no back-up plan for how to move the waste or where to take it if trouble develops.

“This approach defies common sense,” said Caroline Petti. “If DOE finds out after the fact that WIPP isn’t safe, they’ll have to retrieve the waste and ship it back to the original storage sites. Transport corridor states will get it coming and going. It’s in everybody’s interest to establish whether WIPP is safe before loading it up.”

Such concerns don’t bother local WIPP supporters like Mayor Robert Forrest of Carlsbad, New Mexico. To the mayor, nuclear waste means money and “good jobs” for an area fraught with low wages and high unemployment — an estimated $700 million and 685 jobs to date. Besides, he said, WIPP is better than other government nuclear facilities.

“If the public knew what went on at Los Alamos, Rocky Flats, Sandia, those mountains behind Albuquerque that had the warheads in them, if they’d have had to pass the tests we had, they’d have never got the door open,” Forrest said.

Not everyone who has lived in the area agrees with the mayor. Lois Fuller, an environmental activist in North Carolina, spent her first 35 years in New Mexico and organized opposition to WIPP in the 1970s. “We were very concerned about the transportation to WIPP,” she recalled. “We were concerned with all the logistics involved in creating something 2,000 miles away from where it would be stored.”

A Legislative Roadblock

The final roadblock WIPP must surmount is congressional approval: Congress must give the final go-ahead before the DOE can begin waste shipments. Land withdrawal bills pending before both houses would transfer permanent control of thousands of acres of federal land in New Mexico to the DOE.

Many senators and representatives remain skeptical of the WIPP plan, and it remains uncertain whether Congress will transfer the land to the DOE. “Why are they trucking waste around when they don’t even know if their site will hold it?” asked one Southern congressional source.

Some lawmakers, like Democratic Rep. Bill Richardson of New Mexico, say Congress should withhold approval until the DOE trains and equips emergency response teams along waste transit routes, builds by-passes around major population centers, and proves that WIPP can meet federal limits on the amount of radiation that can be released into the air and water. Activists like Caroline Petti say legislators should also establish an independent safety board to oversee DOE operations at WIPP and other nuclear facilities.

Tennessee activist Leon Lowery stresses that citizens concerned about the environment should push their states to pass stronger laws governing nuclear waste transportation. “Whoever owns or is carrying the waste should pay the real cost of emergency training, equipment, and all the other costs of waste transportation,” Lowery said. He is lobbying for a Tennessee bill that would require the DOE to notify states of upcoming military waste shipments, pay a $1,000 fee per shipment, and let states have a say in deciding what routes the waste will travel.

In the end, what happens on Southern highways will depend on how extensively citizens get involved in the controversy over what to do with radioactive military wastes. So far, few citizens have actively demonstrated against WIPP or the corporations that stand to profit from the waste-transportation business; most of the opposition has focused on pressuring state and federal lawmakers to enact tougher controls on how nuclear wastes are handled. In the meantime, the DOE is moving ahead with its plans to truck nuclear weapons wastes through hundreds of Southern communities, even though few Southerners have had a say in decisions that will directly affect their lives.

“The greatest danger is to people being exposed along the transportation routes,” said Melinda Kassen of the Environmental Defense Fund. “We think the citizens who’ll be on the road with this waste should have the chance to comment on it and make the DOE justify it.”

For more information about WIPP, contact the Southwest Research and Information Center in New Mexico at (505) 262-1862, or write the US. Department of Energy, P.O. Box 2078, Carlsbad, New Mexico 88221.

Tags

Wells Eddleman

Wells Eddleman is an energy and environmental consultant in Durham, North Carolina. He has been active in nuclear waste issues for over a decade. (1988)