This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 3, "Mint Juleps, Wisteria, and Queers." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

The following article contains anti-gay slurs.

On Route 48 the directions blow out the window. I call R. from a MacDonald’s somewhere. I’m late so he tells me about a shortcut. Take the second or third Summerton exit. Turn back under the highway; there may be a sign. After so far, turn right. Cross fishing creek twice. Eight to ten miles. Top of hill. Pecan trees. No, no landmarks. Everybody knows me, if you get lost.

Tobacco’s turning bright yellow. The heavy air smells like grape Nehi — kudzu must be blooming. His vague instructions, the haphazard distances, would apply in most any direction. He could be 30 miles back the other way by now.

Justus Seed Farm Road. Half Acre School Road. A worn farm town at a crossroads. A jumble of dusty rockers and pitchforks fills one window of the general store. Seems like he could have mentioned road names, or towns. Somebody’s lettered a sign that says “RABBITS” in a yard where bottle-gourd birdhouses hang way up on crooked crossbranches.

Ahead something black unfolds, spreads out, lifts off and soars. Buzzard. The grinding sound from the left front wheel’s getting worse. Down a hill. Across some creek.

“Godforsaken wildernesse!” bellows a European adventurer as his horse sinks up to the saddlebags. I imagine R. sitting at home, smiling slightly. What, after all, are transitory towns and road signs when your people have been here since time began? “Everybody knows me,” he says as I pass houses where brown, impassive families sit in the shade.

At the top of a long rise, a colonnade of pecan trees watches over an old house. I holler through the screen door: my voice hangs in the dark parlor. Here and there are signs, finally. This is his place after all.

Next door, an old sprightly Indian woman, R.’s mother, chats at the kitchen table with a big rough-hewn black woman. We exchange pleasantries and they resume their talk of family in voices strange to my ear. R. and I put together a lunch— fried chicken, thick soup, butter beans, sweet potato pie, watermelon, ice tea—and then we walk back through the pecan grove and settle in his parlor.

“Whooooooeeeeee!” he squeals, tasting the soup. “Take somebody mean to grow peppers that hot!” I start with the pie myself, and surmise that his mamma must be infinitely kind.

“There were all sorts of landmarks, and those roads do have names.”

“Why confuse you with details?” he asks loftily over a chicken leg. His dark eyes are laughing.

This afternoon we aim to record R.’s stories as a gay man native to this place. Where shall we begin?

Naming. That seems a good place to start. Straightaway R. chooses Rabbit. “I’ll be Rabbit!” he laughs, raring back in his sawed-off straight-back chair. Rabbit the trickster, the sly joker. And I’ll be the credulous European in a new and ancient world.

Rabbit’s people will be the Birds. Through all the open windows come their soft chirps and sweet whistling.

Very few people can say, “I am where my ancestors have been before the memory of man runneth to the contrary.” We get all these white theories about the Bering Straits, Polynesia, the Vikings, all that silliness, but we know we’ve been here forever.

Being nature and being a part of nature — a natural spirituality, a natural harmony — that’s what is essentially Indian for me. And also it’s about family. There’s an immediate, present sense of your own identity because everybody else in the family and in the tribe is a clone of yourself. So you look at yourself, everywhere you go, you look at yourself.

There’s a drawing that John White did around 1585. It’s called “The Flyer” — probably a conjurer, a shaman, homoerotic. He’s almost naked, with a dried bluebird attached to the side of his head, and he’s literally in the air, dancing, flying. An Algonquin ancestor. He looks just like a boy up in the community, a cousin. Every time I see him I tease him about being the flyer or the conjurer.

One tiling about pre-Columbian America was the virgin forest — climax-formation forest. The sweetgum and pines are the first trees to come back after a fire. Then the oaks force the pines out and form a canopy over the forest floor, and you get the dogwoods and hollies and ferns. It’s nothing like the savage wilderness that the white folks described when they came here. The oak trees are a cathedral with the sun shafting down through them.

So it was a Sunday night. I took some acid maybe around seven o’clock and I finally got out of the house around ten. I went to Elora; there was nothing happening there. And I drove to Mayhew, it was a little bigger, but there was nothing happening there, so I decided to come back to the disco in Pleasant Hill, where the families are. My great-great-grandfather’s house is on one side, and my uncle’s house is on that side, and my granddaddy’s house on this side. It’s on a knoll right in the middle of the community, on top of ancestral ground.

The two brothers who run the place were closing up. I mentioned to one of them I wanted some firewood. He said, “Well, hang around. We can talk about it.” There were about six or seven guys still there. The older brother was high and when he realized I was tripping he went and turned the sound system back on, and when he did the light system came on too, and the spotlights came shafting down through the dark of the empty dance hall.

I was halfway conscious of the song he kept playing over and over — “You so fine. You got style, you got grace . . .” Over and over, so I get up and start dancing, with the light shafting down onto the dance floor in the semidarkness. Suddenly I flip into the world of the virgin forest, with the sun shafting down through the oak trees. Climax-formation forest. I strip naked and I’m dancing native. “You so fine. You got grace.” Naked, dancing. Ancestral ground. And then everybody else was naked, and we were having an orgy!

Here in the community people know that I’m Indian, of course; but I go anywhere else, they assume I’m black. You see it just goes to show we all niggers in America, unless you’re white.

In the early ’60s, when I first went to college, there were nine of us. We were these nine “others,” these nine niggers, right? There was a restaurant outside of town that wouldn’t let black folk in. It didn’t matter whether you Indian or black, they wouldn’t let niggers in. So we go out there — nonviolence, right? “Go limp.” So we going limp and this big white woman pulls up her dress and starts to piss on me, saying, “This, nigger, is the closest you gonna get to white pussy!” And I look at her — it’s such an irony because I’m a faggot, and I don’t want no white pussy!

Years later, up north, this dark man automatically assumes that I’m a mulatto. He don’t know that I’ve been pissed on in civil rights, protesting a segregated restaurant. He spits in my face! Says, “You probably love having all that white blood.” And you know, I’m speechless! Now I’d sock the shit out of him first, but I say, “Goddamn, I been out there fighting for your ass and you’ve got the stupidity to spit in my face!”

You get a lot of that still — how homosexuality is a form of genocide against blacks, and that the only reason you find black guys sleeping with faggots is that they were trying to make some money to survive, to get bread for their babies. They say that AIDS is something that the white boy put on black folk, right?

Rabbit slumps down in his chair. The room is quiet, except for the ice in a glass of tea. We look away from each other. Bird songs embroider the late afternoon.

The curing season . . . Hear that?

I hear a machine’s persistent hum from across the road.

That is a gas-fired, bulk tobacco-burning barn. Ruins the night. You be out there listening to the cicadas and the crickets, the stars like moons, so bright and beautiful, and then there’s this fucking bulk-barn blower.

When I was a kid, the tobacco barn had one of these molehill furnaces, and you had to cut firewood to feed up into the stone furnace, which cured the tobacco inside. You had a hammock and you had to sleep down there, to stoke the fire every hour. You’d go down with your daddy and you’d just sit and watch the fire, not saying a word. Listening to the night. Curing. And the wonderful smell of tobacco in the air. That’s how you knew the curing season was on.

When he was a boy, my uncle came up unawares on my great-granddaddy one night. My great-grandma happened to be down there in the hammock with my great-granddaddy and they were fucking. So my uncle just stayed in the dark and listened and watched. My family has always been educated and propertied and very respectable, but there is Great-Granddaddy in the hammock fucking Great-Grandma! And she’s saying, “Oh, Mr. Bird! It’s so good, Mr. Bird! Ohh, ohhh, OHHH, Mr. Bird! Mr. Bird! Mr. Bird!” And Rabbit hunkers back and howls in ecstasy and claps his hands. Aaah, the curing season.

Did I ever tell you the story about my uncle and this white boy who had the local grocery store, where they sold on credit, and at the end of the year you had such a bill you never could pay up and then you started the whole shit over again the next year. He and this white boy would sit around the store joking about who had the biggest dick. So finally one day he say, “I’m getting sick of you telling them lies about your tiny white dick!” “And I’m sick of you, nigger, telling about your big dick!” “All right, let’s have a contest!”

So the white boy says, “Go bring me a gallon fruit jar! I’ll show you my dick is so big it won’t fit into the mouth of a gallon fruit jar!” So my uncle says, “Go bring me a pickle jar! Show you my dick is so big it won’t get into the mouth of a pickle jar!”

Well, years later my uncle’s in the hospital and he’s lying there in one of those hospital gowns, a big-boned, beautiful man with straight black hair. I had wanted to do this all my life, because when I was a child he would come and he would grab my knee, and he would squeeze it real hard, and look me right in the eye, and I was like a deer flashlighted at night, mesmerized — and being the faggot that I was, loving it!

So to get back at him for squeezing my knee all those years, I grabbed his dick and squeezed it! It was a shock! If it had been a heart problem he would have had a heart attack. And then he burst out grinning! He grinned and he grinned, and I grinned. I shook that thing! It was like squeezing a big Coke bottle!

I was a sharecropper’s son. We’d start in January, clearing the tobacco bed, preparing it to plant. Then we’d break land as soon as the rains stopped. And then once you got the tobacco growing, you plowed and chopped and plowed again. I walked a hundred miles a day behind those two mules.

I’d go to school maybe the first couple of days, register and get my books, and then I’d stay out and help finish priming the tobacco, and tying it up at night to get it to the market.

But there was time for pleasure, too. Rabbit enjoyed the company of the older boy across the road, and two cousins. They carried on “with impunity” in the back of the neighbor’s daddy’s car, circle-jerking and sucking. From age 10 or 11 on, though, his true love was Jimmy, the son of a black lumberjack. Their family lived a feral existence far from the road. The hulking lumberjack skirted through the pasture, dreading Rabbit’s grandmother’s chickens, and the littlest boy would take off for the woods running when Rabbit approached.

Jimmy was always around. I don’t think he ever had gone to school. We made love everywhere. Even in the curing barn one time, with the furnaces going and maybe 130 degrees heat. I was 13 or 14, hanging from the rafters, and we were fucking and sweating and every time we come together we be sloshing and the sweat would fly everywhere and you’d hear this deep “slush” sound. Whap! Whap! Whap!

My daddy had a ’59 Impala Chevrolet, and I just hated that goddamned car because I had to learn to drive on it. I’m a country boy, right, and they make you parallel park. You know how big a 1959 Impala Chevrolet is? Took me five or six times to get my license. So, I’d be sitting in there, playing like I’m shifting the gears. And he’d be standing outside and he’d get a hard that would go down his pants. And he’d take it out, and we’d play with one another, and the family would be sitting right there on the porch, unaware.

It was what got me through adolescence really, that friendship. After that, I suppressed everything, sublimated into studying and trying to get away from the farm, being valedictorian and getting a scholarship and getting off the farm. I be damned if I was going to be a sharecropper.

During my sophomore year in college, I was home and Jimmy’s little brother came to visit. “How’s Jimmy?” I asked him.

“Haven’t you heard?”

“Heard what?”

“Well, his woman shot him.”

He was married and had kids, but it turned out he was living with this other woman. I think she lived with her mother, and he was staying there with them. He had made some comment at dinner about her mother, and then he went to take a bath. She came in and said, “Do you still mean what you said about my ma?” He said, “You damn right!” And she shot him, dead.

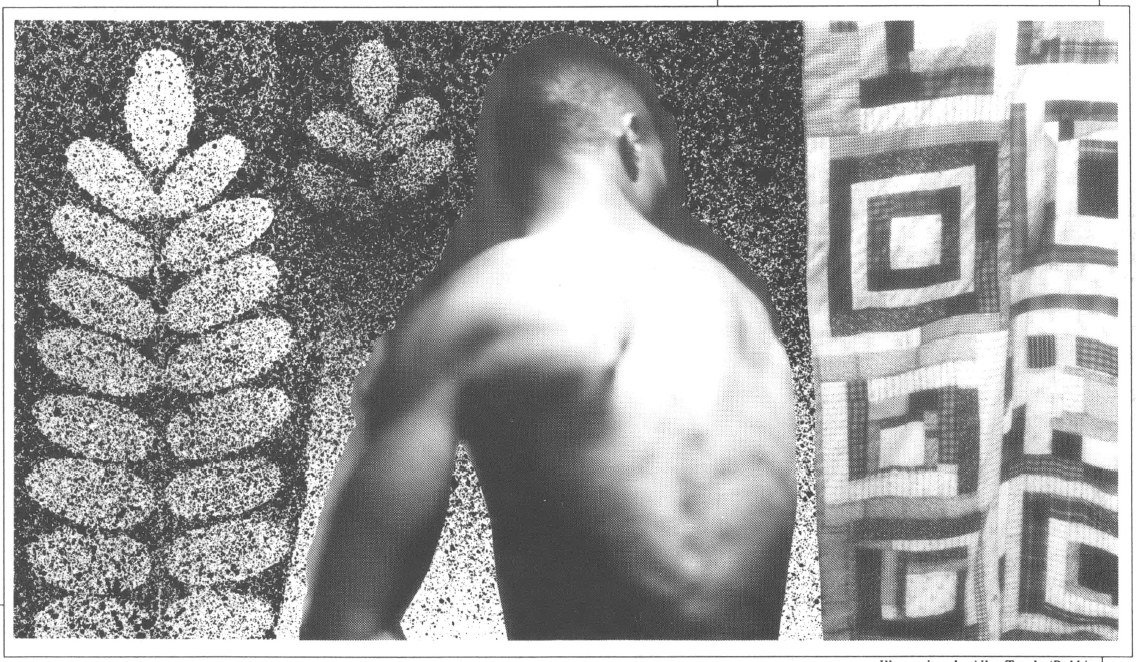

In the backyard, a little brown rabbit watches while I pee. Then, all weightless nerve and muscle, ear and whisker, it arcs away. Rabbit dreams sometimes of Indian youths setting off on vision quests in emblematic quilts. I ask him, what of his own experience?

Well, there was the quilt his grandmother made when he left for college, and there were epiphanies along the way, as he became student, poet, lawyer, art collector. Far away, in a three-piece suit, he found himself walking down 5th Avenue after lunch, playing spoons. Clickety clickety click. Waiting for “wait” to change to “walk.” Clickety click. The next day he told the office he had another job, somewhere else. Soon he was home. All his aunts gave him quilts for his new life, on ancestral ground.

Rabbit has never told his family he’s gay. “I don’t think it’s necessary,” he says, “because it’s understood.” He’s sure his daddy knows because he rescued Rabbit once from a couple of men he’d brought home — rough trade who were getting mean. And his mother doesn’t pressure him to get married or to find a woman. “You need a friend,” she suggested a while back. Rabbit shook his head and said, “You damn right I need a friend.”

What of his search for friendship? And what about Indianness and blackness along the way?

“I’m an Indian,” Rabbit says. “I deal with blacks. I deal with Indians. I don’t deal with whites. Is that what you mean?”

In its blunt way, I reckon it is.

By happenstance, Rabbit’s early partners for sex were black. In an apartheid world which reinforced the closeness of blacks and Indians—Rabbit’s birth certificate reads “Colored” rather than “Indian” — Rabbit’s light skin was sometimes a sign of the sissy, while “the real men, the athletes, were these black guys, the so-called ‘mandingo’ types.”

I started first grade in a four-room schoolhouse. “The Pleasant Hill Julius Rosenwald School” it said above the portico. It had pot-bellied stoves, and of course it had an outdoor john. The students when they took a leak stood around this circular well-casing and pissed in front of one another. And I loved it.

In retrospect you wonder, how did you get away with all these things that you now know were connected with your sexuality and sexual interest? Like raising your hand, saying, “Teacher, may I be excused?” to go every hour on the hour to check out the pissoir. At the time there were poor boys who had to stay out to work, 16, 18 years old. They’d come the first day and then they’d come back when it snowed or rained. And I loved it, these huge mandingos, mature farm men, pissing right in front of me!

In my sixth-grade year, after integration, the county said, “We don’t want you, but we gonna give y’all the best facilities so y’all can’t say that you not equal.” So we got brick schools and central heat and indoor toilets! And they tore the pissoir down!”

“Anthrophilologist.” That’s what Rabbit calls himself. A significant part of his fieldwork has been conducted in and around the pool halls nearby. Watching, listening, “trying to absorb the scene.”

It’s the only thing in town, right? A funky jukebox, a couple of pool tables, guys standing around the wall watching. Too broke to play or to buy beer. Just hanging out because there ain’t nowhere else to go. You have to learn the signals: “You can wink at me and I can follow you out, but you better not speak to me, and I definitely ain’t gonna speak to you.”

But if you get them around the corner, then you can deal. You say, “Hey! What’s happening? Want to smoke a joint?”

“I know what the deal is,” he’ll say. Which means he understands that we can get together and have sex. And the second aspect of that is, “The deal is that we can deal. You make me an offer and I’ll think about it.” There’s a quid pro quo. It’s not hard and fast, but there has to be something.

It could be, “Why don’t you buy me a pack of cigarettes, man. Yeah, we can deal.” Or, “Hey man, you know, I need a couple of bucks to get me a haircut. You know what the deal is.”

Or it can be more outrageous. “Hey man, I need a new pair of sneakers. I can’t come see you if I can’t get no sneakers to walk on, man. You know the deal.”

And part of that deal in a third sense is, “You’re the sissy, and I’m the man. I fuck you, you suck my dick, but I ain’t gonna do none of that shit. You know the deal.” It’s a way of doing what you want to do, maybe getting something out of it in a financial sense, and preserving your macho.

Or, “Hey man, I got a wife, I got a girlfriend. What am I gonna get out of this deal? I’m not gonna enjoy this. If I wanted to get off, I’d go and fuck my old lady!” And I say to myself, “Well shit, why ain’t you at home fucking your old lady?” He probably doesn’t even have an old lady, which is also part of the deal, right?

It may be that people have to sell their bodies out of economic circumstances, but I think that’s de minimis in terms of the attraction of men to one another. There has to be a homoerotic element to that tum-on.

Well, anyway, it was March 1985, and this man walked up to me at the pool hall and he says, “Hey, how did those pictures come out?”

(For years Rabbit has used his camera as a lure, introducing himself as an amateur photographer and asking guys to model for him.)

I just looked at him. Didn’t know who he was. I said, “What? What?” And then I remembered him.

About six months earlier I had been riding from Pleasant Hill to Wisdom and I saw him walking down the highway in nothing but a pair of cutoff jeans. I was zooming to get to someplace, and then as I got down far enough to where he was in my rearview mirror, I picked up that he was standing in the middle of the road, looking, facing in the direction I was going, which was the opposite he was going. So I said, “Well, damn! I should go back.” So, I had my camera and I went back and said, “Let me take a picture of you.” He said, “Sure.” So he stood there in the middle of the road while I took a couple of shots, and I moved on.

At the pool hall, I thought he must be trying to cause trouble. He said, “What’s happening? Let’s do something.” I said, “I’m just hanging out. Just needed to get out of the house and have me a beer.” But he wouldn’t be put off, so finally I said, “Look, let me finish my beer and I’ll think about it, maybe.”

So he wanders off and I forget about it and maybe a half an hour later he comes back around. “Haven’t you finished that beer yet?” I said, “Damn, I need to deal with this man and see what he’s about.” So we walk out of the place together, and everybody knows. I had been going there for years. He knew what the deal was.

He says, “Of course this is going to cost you.” I said, “I’ll take you home. Where do you live?” And he said, “All right, I’ll treat you tonight.” I said, “Whatever you want. Because I can take you home.” He said, “No. Go on.”

And so we get out here, and we spend the night, and it’s wonderful.

His name was Anthony and Rabbit didn’t see him again for several months. Then one Sunday afternoon he came back.

He wandered around the house and he saw a chessboard that a friend of mine had given me 20 years ago. He spread it out on the daybed, set it up as a checkers game and said, “Come on man, let’s play checkers.” So we played checkers with my chess set all afternoon, and the more and more we played, the more I fell in love with him.

I had had this fantasy since childhood, since playing with the black dude across the road, of having a local, farm black man as a lover. I felt like this fantasy had just walked up to me.

At first, as Rabbit and Anthony negotiated their quid pro quo, there were steak dinners on Tuesdays and Thursdays at a stcakhouse decorated with a mural of the Matterhorn, Saturday afternoons getting high, naked, watching the baseball game, and trips to the beach.

Then the deal escalated. “He was less and less giving, and I was totally in love.” Rabbit sold his art collection, so they dined at the Rainbow Room and the Top of the World, and they discoed all night. “It was the only place that he would dance with me, in New York.”

At sea, on the fishing boat he rented just for the two of them, Rabbit vomited for four hours and Anthony caught two sharks. Rabbit shows me a snapshot from that outing. A dark, young, powerful head stares off to the horizon. Blue-green ocean, blood-red tee shirt.

“In January of ’87 he tells me, ‘Hey man, my girlfriend just had a baby.’ Turns out the boy’s 16 years old and he’s got a girlfriend and a baby! Triple shock!”

The girlfriend dropped out of school, moved into Anthony’s bedroom, and they were man and wife. “I would call and the baby would be crying in the background. Or she would take the phone and demand, ‘Who’s this? Who’s this?’”

One phone call, Anthony told him, “Hey man, I’m about to get on the busfor New York to go live with this dude.”

When I called back, I got his mother. I always felt terrible in terms of the mother, because if I were a parent and I had some man calling there for my 16, 17-year-old son, I would want to shoot him.

So I said, “May I speak to Anthony?”

“He’s not here.”

“You expect him?”

“No.”

“I understand he went to New York.”

“Yes.”

So I said goodbye.

(I had asked him about rabbits, what he recalled. As “a child of nature” he would come upon their nests in the fields, filled with tiny balls of fur. Then he paused.

You know what a rabbit gun is? It’s like a long wooden box with a trap door. You lure the rabbit in with onion or apple inside. And once he gets in deep enough, he trips a little stick that’s in the middle of the gun, and the door collapses on him.

I’m sure it’s native. What they did was they burned out logs to use, before boards and European tools. My daddy still sets out four or five of them.)

My grandmother’s room off the parlor was a quiet reserve, and in the evening she would usually be sitting there in her large armchair, reading her Bible.

We didn’t talk that much. Sometimes, when I was younger, I might ask some silly kid question, but when you grow up in an extended family, before long you know everything. She wore her long grey hair in a chignon, and at night she would pull the tortoise-shell combs out and let her hair down to her waist. Then, with a dramatic gesture, she would bend over, put her hands behind her neck, and flip her hair over her head. She looked ghostly with her long hair covering her head, when she bent over like that.

She would brush it over and over again, from the back to the front. Such a laborious thing to do, to keep brushing and brushing her long hair.

In her room there was a sense that time really didn’t change. The present was no different from the past, and the future, more than likely, wouldn’t be different either.

That was what her room was like. Timeless. Outside of the house. It was this eternal world where you suspended disbelief. The world where art exists.

She was an untouchable fairy godmother, and I said, “I can go into this world. I’m coming in.”

I’ve always taken risks.

Tags

Allan Troxler

The author lives and works in Durham, North Carolina. His interview with Robert Lynch, entitled “Rabbit," appeared in the Fall 1988 issue of Southern Exposure. (1988)

Allan Troxler is a dancer and artist in Durham, North Carolina. (1988)

Allan Troxler is a staff member of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1979)