No More Back Seat

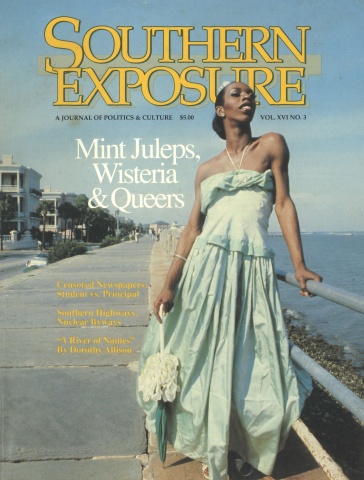

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 3, "Mint Juleps, Wisteria, and Queers." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

Bayard Rustin was a long-time civil rights activist known as a skilled organizer with a passion for details. He was chief organizer of the 1963 March on Washington, which drew more than 200,000 people and was credited with pressuring Congress to pass the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

A self-acknowledged homosexual since the early ’60s, he was also, in his later years, an outspoken advocate of gay rights. “We have got to get gay people to do now what blacks did in the ’60s,’’ he once said. “Until they come out and get into political action, we are in trouble.”

Rustin died on August 24, 1987 at the age of 77.

Veteran civil rights activist Bayard Rustin discovered gay pride one day in the 1940s on a bus in a Southern town. It was a revelation that would change his public and private lives for many decades to come.

“I was prepared to do what I’d always done in the South,” Rustin recalled, “and take a seat in the rear.” But as he walked down the aisle, a small, white child playfully grabbed for his red necktie. The child’s mother quickly reprimanded, “Don’t touch a nigger!”

“Something happened,” Rustin said in an interview in his New York office. “I thought, ‘If I go and sit quietly in the back of the bus now, that child . . . is going to end up saying, ‘They like it back there. I’ve never seen anybody in the South protest against it.’ That’s what people in the South said.”

When Rustin realized that his acquiescence to prejudice made him a party to it, it was a double epiphany. Not only did he stay in the front of the bus for that trip, but shortly afterwards, he told each of his friends that he was gay. “The only way I could be a free, whole person was to face the shit,” Rustin said.

As a young man, Rustin had always been tough. He loved sports and won four varsity letters in school. He already knew he was gay then.

“It was all extremely romantic,” he said, “but the consequences of being gay didn’t really strike me until I got to college.” There, he said, he felt so much conflict that he quit college after a year and a half and never got his degree. “I must have 25 or 30 honorary degrees,” Rustin chuckled, “but no earned one.”

After that, Rustin, a wiry and energetic man, often faced and fought prejudice against him for being gay as well as black. Most famous was the attempt by Republican Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina to discredit the 1963 March on Washington, which Rustin coordinated, by gay- and red-baiting the activist in a public tirade before the Senate. But the sponsors of the historic march stood behind Rustin.

“Nobody should have to earn the right to be defended,” noted the veteran of human rights campaigns in South Africa, Southeast Asia, Central America, and the United States. “But the reality is, if you defend the rights of others, they will almost automatically defend your rights.”

Despite his commitment to solidarity, Rustin was “dumped” by Martin Luther King Jr. because of fears among civil rights strategists that then-FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover would use Rustin’s homosexuality to discredit King.

“Hoover began circulating all kinds of stories about King, one of them hinting that there might be a homosexual relationship between us,” Rustin said. Although King would steadfastly support Rustin after Thurmond’s tirade, “I just wish he had showed that strength in ’62. It was painful, I will admit it,” Rustin said. But, he quickly added, “It didn’t hurt our friendship.”

Rustin’s experience on that Southern bus had another major effect on his life. After telling his friends he was gay at age 35, Rustin’s life opened up to having more serious relationships.

“There was a period when I was promiscuous,” he said with a slight smile. “I don’t mean I was running out every night, but I had a series of one-night stands. Not until I declared myself could I build these associations,” he said. “If you are hiding things, you can’t get too close to people, even gay people. Therefore you set up false relationships.”

Rustin said it was hard to meet other gay men in those days, especially because those involved in the civil rights movement were in the closet.

“I found out later that many of the people I’d known over the years were in fact gay,” Rustin said, shaking his head. “That’s the reason I want as many young gay people to declare themselves. Although it’s going to make problems, those problems are not so dangerous as the problems of lying to yourself, to your friends, and missing many opportunities.”

Although Rustin found it difficult to make what he called “appropriate friends” for many years, he eventually came to know many gay people who were leaders in organizations like the Urban League, the NAACP, and 100 Black Men. And while in his 60s, he fell in love with a man with whom he lived until his death last year.

His lover, Walter Naegle, worked closely with him, traveling along as Rustin’s work took him to all parts of the globe. Rustin said he had met more of gay society through Naegle, and the two even went out dancing at an upper West Side bar once in a while.

“Until this last relationship, which is now going into its tenth year,” Rustin said with obvious pleasure, “I didn’t really know what it was to have a relationship . . . with absolute, total confidence, no lies, no pretenses, no defenses.” Smiling again, he added, “It takes time to do that, and it took more time with me than with most, I hope.”

Rustin’s civil rights efforts never slowed down. At age 76, he no sooner returned from a meeting in India than he was off again to Trinidad or South Africa. He claimed the variety of his projects was “rejuvenating.” And although a talented guitar player and tenor in his pre-activist days (he performed with Leadbelly in New York’s Cafe Society), Rustin showed no regret over his vigorous path in life.

“Once in a while, when I hear Segovia or a classical guitar, I wish I kept on,” Rustin said, admitting that life as a musician would have kept him in much gayer company over the years. “But it passes with the next trip to Africa,” he laughed.

Tags

Peg Byron

Peg Byron is a reporter for United Press International in New York. This profile originally appeared in the Washington Blade. (1988)