This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 3, "Mint Juleps, Wisteria, and Queers." Find more from that issue here.

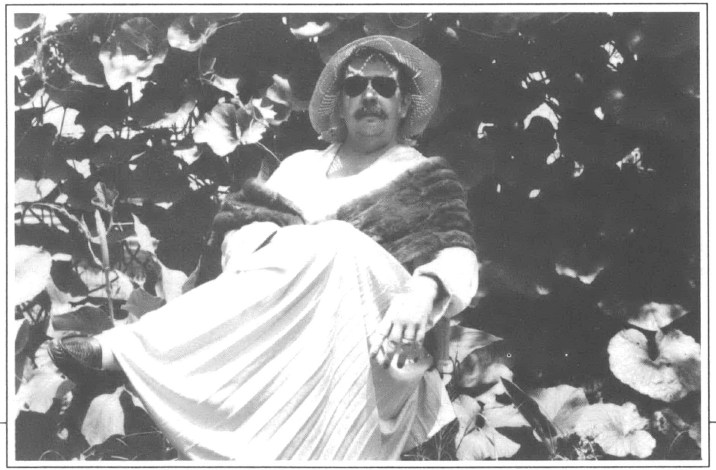

The new Empress of Short Mountain wore royal purple to the coronation: a billowing ankle-length dress made from yards and yards and yards of polyester. On his head he wore a wig of rainbow-colored shredded tinfoil; on his feet, brown sandals. (“I didn’t have purple pumps,” he recalls.) No jewelry or makeup, because “I didn’t want to be too outrageous.”

The outgoing Empress, who didn’t want to give up the crown, tried to delay the coronation as long as possible. But as the afternoon wore on, the 50 men gathered at Short Mountain that weekend grew impatient and began donning their dresses and tiaras. Finally a critical mass was reached, and — ready or not — the festivities began.

The procession wound from the front porch of the 145-year-old house, down the goat-shit-covered path to the knoll. The paraders rang bells and chimes, shook tambourines and gourds, beat drums, and carried wind socks. Along the way, they stopped to pick up the new Empress, 47-year-old Gabby Haze, and his purple-clad attendants. Laughing, dishing, shmoozing and making minstrel sounds, they paraded down to Short Mountain’s outhouse, where the coronation was to begin.

“It was almost as if we were trapped in a Monty Python film,” recalls Raphael Sabatini, a visitor from Louisiana that weekend.

At the outhouse (also known as the “chapel”), the wind mercifully blew in the right direction. Outgoing Empress Stevie sat on the throne, a high-pointed oak bishop’s chair. Gabby knelt at Stevie’s feet. After confessing that he really didn’t want to relinquish power, Stevie finally gave up his crown and wand. Gabby ascended the throne. Cameras clicked. People cheered. A new Empress reigned over Short Mountain Sanctuary, the greatest (and only) faerie community in all of Middle Tennessee.

Beyond the Bars

Across the South, there is a network of rural sanctuaries where gay men gather, far from the bars and the tension of the city. Some are communities where people live in groups year-round; others are stewarded by one or two people when gatherings are not in progress.

They run from Running Water and Willow Hollow in North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains, westward to Short Mountain in Tennessee, down to Manitwo Farm in the Ozarks of Arkansas. They include Briarpatch in the pine forests of central Louisiana, all the way to Gray Lady Place near Dallas, Texas.

Together they make up the South’s faerie community, “a network,” in the words of one manifesto, “of workers, artists, drag queens, political activists, magickians, rural and urban dwellers who see gays and lesbians as a separate and distinct people with our own culture . . . and spirituality.”

Some faeries live in the countryside and say rural living is a necessary part of faeriedom. Others live in the city, escaping occasionally to pay homage to Mother Earth. Some are pagans, some are stockbrokers. Some believe crossdressing is an important way to explore one’s feminine side; a few wouldn’t be caught dead in a dress. Some practice alternative medicine such as acupuncture. Almost all believe there is magic and healing energy to be gleaned from the earth, the trees, and the rituals created by gay men gathering in the woods on a dark night.

Gabby Haze, the Empress of Short Mountain, likens faerie culture to weaving. “When you do weaving,” he says. “you’ve got threads that run up and down. And through them, you weave your colors back and forth.

“I think the thread running up and down is our being gay men. And all these other things — pagan worship, love of the land, drag, ecology — are the colors we weave back and forth that binds us all together.”

But the biggest draw of faerie culture — what brings men to gatherings year after year — is the sense of brotherhood and family that rarely exists in the bars of Memphis or the streets of New Orleans. Gay men flock to gatherings at places like Running Water and Short Mountain with the expectation that they won’t be judged for being unfashionable or fat, for hugging other men or crying in public, for dressing silly or howling at the moon. They know that if it’s their first visit, there’ll be friends to welcome them; if they get sick, there will be people to nurture them.

“The first thing I noticed [at my first gathering at] Manitwo Farm was that there was such a rallying support for each other,” says Skip Ward of Pineville, Louisiana. “People were asking: How can we care for each other? How can we create a culture for ourselves outside the bar?” At that gathering, Ward — who was 61 at the time — went into the field, picked vines and wildflowers and made for himself a crown and g-string to wear to dinner. “I felt like a little woodland creature,” he says.

Southern Magic

Faeriedom is not an exclusively Southern phenomenon; there are gatherings and communities across the country. But the history — and present reality — of faeriedom is inextricably tied to the South.

The South is home to at least a half-dozen rural sanctuaries, as well as an urban faerie circle in Atlanta. New Orleans once served as the home to one of the nation’s most radical faerie organizations, LaSIS (Louisiana Sissies in Struggle). RFD, the country’s best known faerie journal, is located at Running Water and will soon move to Short Mountain.

In fact, RFD Managing Editor Ron Lambe has observed a “Faerie Belt” that runs along the 36th parallel from Virginia’s Tidewater area, through North Carolina, Tennessee and Arkansas, as far west as Taos, New Mexico. Along that latitude lie many of the movement’s long-established sanctuaries, as well as towns and cities which historically have had strong faerie communities.

Even before gay leader Harry Hay issued a call for the official first “National Spiritual Gathering of Radical Faeries” in Arizona in 1979, gay men were gathering in the rural South to create safe space for themselves and ritual for their communities. Rural land was cheap in the South; the back-to-the-land movement was strong; and the gay movement was at a juncture.

“Gay liberation had reached a certain point,” says Franklin Abbott, an Atlanta therapist and poet. “A lot of us could never quite identify with the assimilationist point of view: that we’re just like everybody else except we suck dick. It just didn’t feel right.” In the late 1970s, gay men began to gather for weekends at Running Water Farm, trying to carve out their own identity — to discover the ways in which they weren’t just like everybody else.

“As gay men, we realized early on in our lives that the [expectations] of society don’t fit,” says Ron Lambe. That knowledge helps faerie men break out of the “straightjacket of society” — to discover the magic of ritual and nature and brotherhood. “That magical, romantic, back-to-nature mystique resonates with gay men,” he says.

One of the events that coalesced the Southern faerie network was the relocation of RFD, the quarterly faerie journal, to Running Water in 1980. (For most of its early life, RFD was based in the Northwest.) Completely reader written, RFD is an amalgam of radical gay philosophy, homesteading advice, recipes, poetry, erotic fiction, notes on Chinese medicine, announcements of gatherings, and letters from readers looking for friends and lovers. “Having RFD here gives us a regional focus, something to come together around,” says Abbott.

RFD Managing Editor Lambe says it’s no accident that the South has nurtured faerie culture. “Maybe the intense alienation from the rest of society that we felt in the South has given us the impetus,” he says. “For us, getting together and sharing and holding each other is so important because it’s so hurtful, so alienating out there.”

At the same time, he says, faerie culture incorporates an important element of mainstream Southern society: an emphasis on the ritual, care and structure that families provide. “Families are small incubator cultures,” Lambe says. “Family is important to Southerners, and for faeries, family is what it’s all about.”

Fire, Water, and Trust

At Manitwo Farm, on the shore of Table Rock Lake near the Arkansas-Missouri border, 50 men stand naked around a bonfire sharing stories of painful experiences and ultimate triumphs. A basket is passed, and everyone puts his bad memories in the basket. Once it makes its way around the circle, the basket is ceremoniously tossed into the flames.

At Running Water, a dozen men sit in a primitive sweat lodge, breathing in herbed steam and chanting the names of pagan goddesses: Isis, Astarte, Diana, Hecate, Demeter, Kali, Inana. More herbs are thrown on the fire, more singing — and when the sweat lodge gets too hot, they run out to a frigid waterfall. One by one, each man stands under the water, his pores flying open as he lets out a scream that pierces the quiet afternoon.

At Briarpatch, 30 acres near Dry Prong, Louisiana, a procession winds its way to an old beech tree, where a short play is performed. Then, one by one, each man removes his clothes and becomes a “living maypole.” Someone lifts his shoulders, someone lifts his back, then his legs, until he is completely airborne, depending completely on his trust of his fellow faeries.

Safe Spirits

Medical reality has intruded on the faerie movement in recent years. Just off the footpath to the house at Running Water lies a memorial grove, encircled with hand-carved stones commemorating men who have died — most of AIDS. At the gathering there this summer, little beepers went off continually — reminders to the four or five AIDS patients there to take their AZT.

Because of the epidemic, “gatherings are more necessary, because people need the love and emotional support and the exchange of information about treatments,” says Milo Guthrie, one of Short Mountain Sanctuary’s founders.

At the summer gathering, Franklin Abbott conducted a healing circle, similar to the ones he conducts at home in Atlanta. About two dozen men paired up, with one member of each couple resting his head in his partner’s lap. Then Abbott talked through a meditation for each couple to visualize, evoking a warm current of healing energy coming from deep within the lungs of one partner and flowing into the body of the other.

As Abbott talked through the healing images, his own partner — a man with AIDS — sobbed, thrashing on his back uncontrollably. “Let it out,” Abbott quietly told him. “Let it all out.”

“I think we have the capacity to provide healing space, whether that’s on our land or in our urban circles — a place where people who are sick or weary or scared can go and be recharged,” Abbott says. Faerie culture, he says, “is the magic that has sustained our spirits.” Even when our bodies are dying, our spirits can stay alive and safe.

Tags

Barry Yeoman

Barry Yeoman is senior staff writer for The Independent in Durham, North Carolina. (1996)

Barry Yeoman is associate editor of The Independent newsweekly in Durham, North Carolina. (1994)