Censored

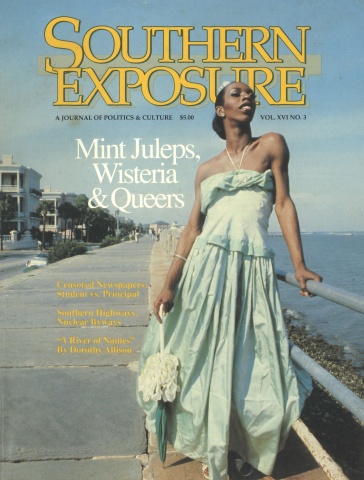

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 3, "Mint Juleps, Wisteria, and Queers." Find more from that issue here.

The Supreme Court says principals can censor school papers, but Southern students are fighting for freedom of the press.

Earlier this year the staff of the Devil’s Advocate, the student newspaper at Stanton College Preparatory School in Jacksonville, Florida, researched and wrote a two-page section on teenage sexuality to coincide with Valentine’s Day. They investigated the growing number of sexually-transmitted diseases among teenagers and quoted statistics on unplanned pregnancies from Newsweek and Seventeen magazines.

Despite the careful research, the articles never appeared in the paper. The school principal, Dr. Veronica Valentine, deemed the stories “inappropriate for publication,” saying they were too sexually explicit for seventh graders at the school. She invoked a school board policy that prohibits discussion of abortion, masturbation, and homosexuality in the school curriculum, even though none of the banned topics was mentioned in the Advocate.

Dr. Valentine also criticized Ingrid Sloth, an English teacher and faculty advisor to the Advocate staff, for failing to submit the articles for approval prior to publication. Although no review policy existed at the time, Valentine said Sloth should have cleared the “controversial” articles with school officials.

Sloth and her staff were confused. They felt their articles were well written and researched and that there was no reason to exclude them from the paper, especially since life-threatening diseases like AIDS make it essential for students to discuss sex openly and honestly. As their censored introduction stated: “The Devil’s Advocate has elected to present the following articles on teen sex because Stanton students are not immune. . . .”

Anna-Liza Bella, the student who edited the section, said Valentine had minimized the importance of the articles by censoring them. “There was a lot of work put into it, and I felt it was not right for her to take it away.”

Sloth and her students were also concerned by Valentine’s stipulation that future “controversial” articles must be approved by the principal before publication. Who had become the editor?

“I didn’t press (the issue) for fear of job security,” Sloth commented. “But my staff will continue to seek out and research subjects that are important to teenage students.”

The Word from on High

What happened to the students on the staff of the Advocate took place only a few weeks after the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a decision in Hazelwood School District v. Kulmeier giving high school administrators the right to censor any articles they deem inappropriate for a student publication. In a 5-3 ruling, the court upheld a 1983 move by the principal of Hazlewood East High School in St. Louis to censor student articles on teen pregnancy and divorce.

It was the first time the court ever ruled on a First Amendment case involving a school-sponsored newspaper — and the Advocate case appears to be the first indication of how some school principals intend to use the ruling to censor students. As a result, many students and faculty advisors say they now fear a new wave of government-sanctioned censorship in public schools.

Until now, school officials could only censor articles that would actually disrupt school activities or invade the rights of others. But under Hazelwood, officials only need what the Supreme Court called a “valid educational purpose” to censor newspapers that are produced as part of the school curriculum. What’s more, they can also censor any other school-related activity that is “not a forum for public expression,” including student plays, art shows, science fairs, debates, research projects, and even cheerleading squads.

In essence, the Hazelwood decision says that the rights of public high school students are not the same as those of adults. The ruling has virtually stripped students of their First Amendment right to free expression and given administrators total authority to censor any articles they don’t like.

Censorship of school newspapers took place long before Hazelwood, but it was constantly being challenged and debated and sometimes overpowered by free-thinking students. In the South, students often took on the censors and won:

• In 1985, student journalists fought back when the school board in Patrick County, Virginia censored an ad in the Cougar Review that urged students who were thinking about enlisting in the military “to find out what you’re getting into.” The school board backed down when the ACLU called the censorship “a blatant violation of required constitutional standards.”

• In 1987 a district judge in Texas issued an injunction against Bryan High School after principal Jerry Kirby suspended student editor Karl Evans for distributing an alternative newspaper containing articles that criticized school officials. In an out-of-court settlement the school agreed to pay Evans an undisclosed sum for the wrongful suspension and to establish a written policy for school publications.

• Last year more than 80 high school students in Arlington, Virginia wore armbands and staged demonstrations when Principal Mark Frankel censored a survey about drugs and alcohol in the school yearbook. School officials finally gave in and agreed to form a publications board composed of students, faculty, and administrators to decide cases involving controversial articles.

Since the Hazelwood ruling, however, student journalists are discovering that what the ACLU once called “blatant violations” are now considered legal. Instances of censorship have exploded across the nation — and the South has not been immune.

A Shooting and a Cover-Up

Last February, less than a month after the Hazelwood ruling, high school students in Pinellas Park, Florida were preparing to print the Powder Horn Press when gunfire broke out in the halls. Two assistant principals had attempted to disarm two students carrying guns, and two shots had been fired. One shot injured Assistant Principal Nancy Blackwelder. The other killed Assistant Principal Richard Allen.

Students on the staff of the Powder Horn Press worked all afternoon to cover the shooting. They redid the front page with a story and photo, designed a graphic for the back page, and raced the paper to the printer by midnight. The paper was printed the next day, but when the students took the articles to Principal Marilyn Hemminger for her approval, she forbid them to distribute the paper.

Hemminger cited Pinellas Park guidelines which state that anything obscene, libelous, or potentially disruptive must be approved by the principal before distribution. Five days later, she ordered students to reprint the first and last pages to eliminate all coverage of the shooting.

Carol Jackson, spokeswoman for Pinellas Park schools, said the story was pulled even after local media had covered the shooting because the back-page graphic slightly misplaced the location of the surviving assistant principal. “Parents know professional press and accept that it has errors,” Jackson said, “but the school press is the official word.”

Jackson said officials killed the story to “calm the frenzy” in the school, adding that it would have created too much chaos to allow the paper to be distributed in the aftermath of the shooting.

Others disagreed. Susan Early, faculty advisor to the Powder Horn Press, said the principal banned the article even though the students’ coverage was more precise than that of the professional press. “We are not afraid to cover things like this,” Early said. “Under the circumstances, we felt this was the best thing to do.” She said students were told they could appeal the decision, but were forewarned that the school superintendent would back the principal.

The decision was never appealed. The Power Horn Press was reprinted without any coverage of the shooting, and an important viewpoint was censored.

Ironically, the front page of the censored issue also featured extensive coverage of the Hazelwood ruling, including reactions from students and professional journalists. In an article headlined “Student journalists denied rights in school,” Principal Marilyn Hemminger was quoted as saying that she “has never censored an article.”

Sex and Santa Claus

Incidents of censorship like this one, following close on the heels of the Hazelwood ruling, have alarmed students and their faculty advisors. The Student Press Law Center, a non-profit group in Washington, D.C. that fights for the rights of student journalists, reported receiving 500 phone calls in the first three weeks after the ruling.

According to many observers, Hazelwood sets student journalism back almost 20 years. In effect, the ruling weakens the standards established in the 1969 Supreme Court decision in Tinker V. Des Moines Independent Community School District. In that case, the court ruled that school administrators could not suspend students who wore black armbands to protest the Vietnam War unless they could show the situation would disrupt school activities.

Alan Levine, a lawyer specializing in student rights and co-author of the book The Rights of Students, said he expects the student press to face more censorship now. “Before Hazelwood school officials lacked the power to censor,” he said. Now, they have the legal ability to monitor the voice of an entire student body.

Part of the problem, advocates for student rights say, is that the Supreme Court ruling allows school officials to censor articles they don’t like simply by deeming them “inappropriate.” In Lexington, Kentucky, officials censored an editorial about sexual activity written by a student at Lafayette High School. The reason? According to Assistant Principal Robert Murray, the editorial gave the impression that “students themselves, regardless of age, make the decision on sex.”

What issues are too sensitive for a student publication? The court gave examples of potentially inappropriate topics, including articles that question “the existence of Santa Claus in an elementary school setting,” or “speech that might be reasonably perceived to advocate drug or alcohol use, irresponsible sex, or conduct otherwise inconsistent with the ‘shared values of a civilized social order.’”

Shared social values? Inconsistent conduct? Free speech advocates say the list is disconcerting because of its vagueness and length. It opens many doors for legal thought-monitoring and censorship in public schools.

But there is hope.

In Dade County, Florida, the fourth largest school district in the nation, students take part in a four-year-old program that grants one high school student a non-voting seat on the school board. That way, when issues of censorship or student rights come up, students are always represented in the discussion.

Sherry Glass, the current student on the school board, said that the seat ensures a student voice in policy decisions. “It’s important for students to have a say in the process that is there for them,” she said. “Too often, students are excluded from the decision-making process and school board members lose the student perspective.” The Dade County plan enables the school to settle issues fairly by including faculty, staff, administrators, and students in the discussion. “I’m there to put the student voice back,” Glass said.

With students on the school board, Dade County has developed a model policy that limits the power of officials to censor student newspapers. The county was also the only school system in the country to file a friend-of-the-court brief in the Hazelwood case supporting the rights of the student press.

Southern students like Glass are supported by teachers who also hope to keep alive the enthusiasm and journalistic liberties that were evident before the Hazelwood decision gave schools the legal right to censor. Ingrid Sloth, the advisor to the Devil’s Advocate, said the Supreme Court ruling made many educators realize that they must fight for the rights of students.

“The big reality that came home to us is that we are living in a very conservative community,” Sloth commented. “As innocuous as these articles are getting every day, it’s disconcerting to realize the politics of the whole thing.”

Nevertheless, educators and free speech advocates insist that the Hazelwood ruling has not killed high school journalism. Students are continuing to struggle to write openly about the issues that concern them, and to convince school administrators that students can never learn journalistic responsibility unless they are freed from the constant threat of censorship.

“No school is required to censor as a result of the Hazelwood decision,” noted Mark Goodman, director of the Student Press Law Center. “Schools that want high quality student publications and a vital educational environment will eventually realize that censorship prevents them from ever reaching those goals.”

Tags

Jacob Cooley

Jacob Cooley wrote this article as an Antioch College intern at the Institute for Southern Studies. He is currently a student at the University of Georgia. (1988)