Boys Will Be Girls

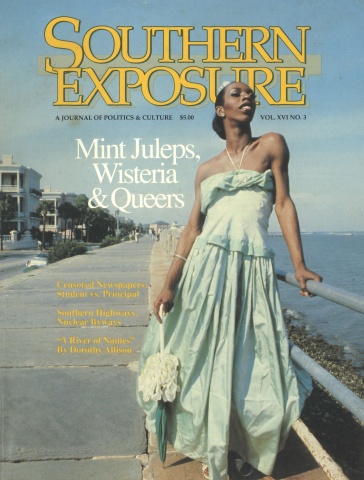

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 3, "Mint Juleps, Wisteria, and Queers." Find more from that issue here.

The scene: a dressing room in a bar in the Deep South. Time: Sunday evening. The music from the disco outside sends a muffled thump against the walls. Inside, in a room lined with mirrors, an 18- year-old man dressed in jeans, sneakers, and a knit shirt begins to undress and start a two-hour transformation. He will change sexes — not literally, but in thought, manner, attitude, and, most of all, in looks. His mother sits nearby, watching as her son pulls on pantyhose and then begins to apply mascara to his eyelashes.

“Are you wearing the blonde wig tonight?” she asks.

“Yes, but I wanted to wear that green dress of yours, too.”

“Now you’re not wearing my best green dress. I’ll not have you ruining it in some show!” Then she adds: “You know, I’d seen drag shows, but I never thought I’d see the day when I’d be helping my teenage son get ready for one!”

The scene is not that odd in the South these days. Almost every small- to middle-sized city from San Antonio to Washington regularly offers female impersonation at the local gay bar, and shows that once played only to gay audiences now draw heterosexual clientele too, at least on show nights.

Indeed, today “drag,” or female impersonation, is far more popular and more prevalent in the South than in San Francisco, New York, or Boston. Drag shows, once limited mostly to convention cities like New Orleans or San Francisco, are now a regular staple in places like Longview, Little Rock, Shreveport, Baton Rouge, Lafayette, Jackson, Biloxi, Mobile, Montgomery, Birmingham, Memphis, Knoxville, Nashville, Chattanooga, and Johnson City. It is big in Oklahoma, widespread in the Carolinas, and down home in Georgia.

Most of today’s impersonators pantomime recorded music over big sound systems, appearing under feminine stage names as colorful and varied as their costumes. Some are alliterative: Michelle Michaels, Daisy Dalton, or Angel Austin. Others try to capture style or personality, like Lady Grace or Hot Chocolate. And still others aim at sexy sophistication or the clever innuendo: Lauren Hart, Vanessa Diane, Toni Lenoir, or Shayla Kruz. There’s even one impersonator named for his car, Gran Prix.

For Shayla Kruz, a 29-year-old impersonator from Monroe, Louisiana, drag is weekend travel, entertainment, and fun. Kruz appears frequently in Texas, Mississippi, and Louisiana, and like most drags who perform today, he books his own appearances.

Trick or Treat

The joy of “dressing up” and performing for crowds is the initial attraction for many female impersonators. In Jackson, Mississippi, two Southern boys discussed how they came to do “drag.”

Angel Austin, 25, had been in the business less than a year. But he recalled how, in the seventh grade, “We used to get dressed up to go trick-or-treating” in his small Mississippi hometown. “We got eggs thrown at us!” He also remembered junior high field day events where, along with potato sack races, there was a “Boys-Dressed-like-Girls” contest.

Angel, who started doing drag shows while working as a house painter, explained: “I always had a sense of how I thought girls ought to look. I’d tell my girl friends in high school how to dress, do their hair, and fix their make-up so they’d look their best.”

Lauren Hart, who appears in Jackson with Angel in a trio known as the Emerald City Dream Girls, and also as a solo performer, said he “had been dressing up in female clothes since age six.” A onetime junior high football player and later a track runner, he said his first experience in female clothes was when his mother made him a Little Red Riding Hood costume for Halloween. After that, “I lived for it.”

He won his first prize for female costumes ($5) at a Methodist Church-sponsored Halloween costume event in the fifth grade. “I’d wear my aunt’s clothes and my grandmother’s jewelry.” After such early success, he admitted, he was hooked: “I’d just get ready to do my annual show.”

So why does the South as a region have such a fascination with drag? A gay writer who lives in New Orleans sat in the French Market coffee house and mused on the subject: “Why, drag is just a continuation of the ‘dress up’ we in the South all played as kids. I can remember my mother used to yell at me: ‘What are you doing in my high heels. Haven’t I told you time and again not to put on my clothes?’” He smiled at the recollection.

Indeed, the roots of sexual role reversal for private and public amusement run deep in Southern culture. Even in Protestant rural areas of the Deep South, one can still find small country churches that stage “womanless weddings” as fundraising events. An entire wedding ceremony is staged, all with men, to the great amusement of the congregation, who pay admission to the event.

In addition, annual “Womanless Beauty Pageants” are still put on at Southern campuses by college students who, for the most part, would be reluctant to recognize the events for what they are.

The Good Old Days

Today’s drag shows often draw critical fire from old-timers in the business who remember the days when female impersonation meant live singing with piano or band accompaniment. One such critic is 65-year-old Gene Lamarr, who began doing female impersonation in the 1940s and worked at it for over 30 years. A singer, he criticized the modem trend toward pantomiming to records.

Lamarr, who once worked at the now-defunct My O’ My Club in New Orleans, a drag landmark from the late 1940s to the early 1970s, spoke of an era when impersonators “had talent.” Unlike most performers of his own era, Lamarr sang operatic arias instead of pop or jazz music.

“I think I was the only one who ever sang opera,” he said. “I was billed as ‘the only true male soprano in America.’” Lamarr recalled how, when performing as a female soprano, he would stop in an aria just before hitting some very high notes, turn to the audience, and say in his husky masculine voice, “Don’t worry, I’ll make it!” and then go back to his high voice to hit the final notes. “The women in the audience would gasp in disbelief,” he said, smiling at the memory.

“You don’t have any talent when all you do is use records,” he declared. “Anybody can get up in front of a stage and pantomime. To have a talent of your own is unique. I still sing,” he added, launching into “Ritoma Vicitor” from Aida, right there in his apartment.

Billy Schreiber was a professional drag in the 1950s. “The problem with today’s younger drag queens is that they overdo everything,” he said. “Too much jewelry and too much make-up.” According to Schreiber, who today runs a nostalgia clothing store in New Orleans, “A real woman doesn’t go out looking that way. The idea of female beauty has always been to do as little as possible so as to emphasize what you already have.”

Schreiber took up impersonation at age 18 after returning from army service in Germany. “Back in the ’50s, it was simply worse to be thought homosexual than it was if you were thought, somehow, to be a woman. If you were small and pretty in those days, you took a lot of harassment. There was a lot of guilt too, particularly if you were Catholic, as I was. I was going with a boy who did drag, and one night he talked me into trying on everything. I kept telling him, ‘I’m not feminine. I have a masculine body,’ but when I got it all on and looked at myself in the mirror, I was amazed.”

Soon, he said, he was doing shows at the Harbor Club on Staten Island, New York and later at the Club 82 on Second Avenue. At first he was billed as “Midnight Blue,” later as “Little Billie.”

Making a Living

Former drags aren’t the only gays who have little appreciation for female impersonation today. Many gay men who have adopted hypermasculine gay images, particularly in large urban centers, also dislike drag for its feminine elements.

“Sometimes the reaction’s been negative,” Angel said. “I was reluctant for a while to tell other gay men I do drag. I guess I was just insecure at first, but it’s all an art with me . . . a job I try to do professionally.”

That view was echoed by 35-ycar-old Rick Carter of Charlotte, North Carolina, who does a comic drag act as “Boom-Boom LaTour” and has been in the business for more than 13 years.

“All of my friends who used to do drag are now pumping iron,” Carter said with a laugh. Carter, who has worked widely — Chicago, Florida, and Georgia, as well as in the Carolinas and Virginia — spoke of the “fun and excitement” of drag, but said he never once thought of himself “as a woman.”

Whatever the underlying reasons for the widespread appeal of drag in the South, the majority of those interviewed — from Texas to Virginia — made it clear that they do not identify themselves as women.

A now retired, long-time impersonator in the South summed it up best. “I never thought of myself as a woman, and I worked in the business for 30 years,” he said. “I was never one of those people who sleep at home in a nightgown. For me, it was a way to make a living.”

Tags

Jere Real

Jere Real is a freelance writer living in Lynchburg, Virginia. (1988)