The Bayou Budget Battle

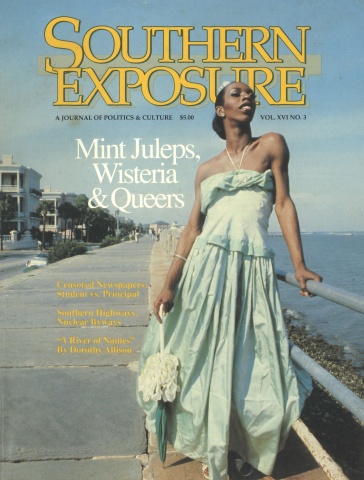

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 3, "Mint Juleps, Wisteria, and Queers." Find more from that issue here.

A huge bronze statue atop Huey Long’s grave dominates the view from the steps of the state Capitol in downtown Baton Rouge, a constant reminder to lawmakers and bureaucrats of the fiery politician who brought about a revolution in Louisiana in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Five decades after his death, the spectre of Huey Long still holds sway over government in the Bayou State. An assassin’s gun may have cut short Long’s meteoric rise to power, but his populist philosophy has survived that bullet.

Some 43 years after Long’s bullet-ridden body fell to the floor of the capitol building he constructed, those marble halls are witnessing another erstwhile revolution. A bright young politician with a gift of oratory every bit as brilliant as Long’s has promised to remake the face of Louisiana state government. Newly-elected Governor Buddy Roemer has completed his first legislative session — and in just three months he won sweeping changes in the areas of economic development, labor-management relations, campaign finance, and education.

But while Roemer has made revolution look easy in Louisiana during his first seven months in office, his progress in the area of state fiscal planning has been somewhat slower. He has managed to bring the state budget into balance, no mean feat given the economic problems the state faces. But he is still at the very beginning stages of his effort to restructure and redirect the way Louisiana government spends its money.

Remaking the face of government in the state poses a tricky dilemma, because populism in Louisiana has two faces. One is the face of activist government, of human services for the poor and fair taxation of business and industry. The other is the face of corruption, of cynical politicians who use populist rhetoric as a smokescreen while they staff agencies with their cronies and feather the nests of their allies with lucrative consulting contracts.

Today, many in the state remain suspicious of Roemer and his calls for reform. Progressives say they have little sympathy for a reform movement whose hidden agenda seems less the rationalization of services than a retreat from a historical commitment to the poor. When reformers talk of tax restructuring, they are not as concerned with creating a stable and growth-oriented base as with reducing the revenue burden on business and industry.

Which side will Buddy Roemer ally himself with as he attempts to shake the foundations of Louisiana government? Will his Roemer Revolution be a bayou version of the Reagan Revolution — making life better for those at the top end of the economic scale at the expense of those at the bottom? Or will he bring a measure of competence to the management of state government — cutting the cronyism and sleaze without sacrificing compassion and quality in human services?

The Kingfish Legacy

Buddy Roemer is not the first governor to attempt to eradicate the influence of Huey Long from state budget policy. Generations of reformers have chipped away at his legacy during brief periods when they controlled the governor’s office or the legislature. But the political heirs of the man who called himself the Kingfish have always out-smarted, out-politicked, and outlasted the foes of populism.

Well into the 1980s, Louisiana government still operated according to the principles articulated by Huey Long when he and his army of sharecroppers, workers, and yeoman farmers seized power from the state’s Bourbon aristocracy in 1928. The central tenets of that philosophy were:

♦ A centralized state government dominated by a powerful governor.

♦ A comprehensive program of government action to provide road construction, education, and social services for the poor and sick.

♦ Paying for it with heavy taxes on business, particularly the oil and gas industry which has flourished in the state since the turn of the century.

From 1977 to 1982, severance taxes in Louisiana (which include revenues from natural gas production) increased from $492 million to $980 million annually. Additionally, the royalties, rentals, and bonuses which the government earned from production of oil and gas on state-owned lands increased from $205.6 million to $653.4 million.

The revenues from mineral extraction were a politician’s dream. They financed a massive program of public works construction and human services with no pain for ordinary citizens. Energy companies merely passed along severance taxes to consumers in other parts of the country, and Louisiana residents pay almost no sales or properly taxes.

But in mid-1982, the boom went to bust. International overproduction glutted energy markets, and prices began to fall. As exploration and drilling for new energy slacked off, Louisiana companies which provided services and products for the oil and gas industry began to lay off workers.

State mineral revenues fell almost as dramatically as they had risen. By the end of fiscal year 1987, the combined total of severance taxes and royalties was down to $714 million, a decrease of almost 150 percent from the high point of 1982.

Republican Dave Treen, who was governor when the bottom fell out, ostensibly believed in reform, but he did not command the political resources to cope with the dramatic turnaround in the state’s fortunes. Edwin Edwards, who beat Treen in 1983, was a philosophical populist unwilling to change patterns of taxation and spending. The result was a state budget that was literally out of control.

On top of that, Edwards was twice indicted on charges that he used his influence to steer state hospital business to some of his cronies and rake in $10 million in the process. Efforts at fiscal reform were stymied. By mid-1987, with its image again tarnished in the national media, Louisiana was teetering on the brink of bankruptcy.

Out of the wreckage of the Edwards administration emerged a governor unlike any who had preceded him in the last 50 years. As a U.S. Representative from northwest Louisiana, Buddy Roemer had been a card-carrying Boll Weevil Democrat who supported Ronald Reagan’s conservative tax and budget policies. But his pedigree was somewhat at odds with the political position he staked out in the 1980s.

Roemer to the Rescue

Buddy Roemer is the son of Charles Roemer II, who served as administrative strongman for Edwin Edwards during his first two terms in office. As commissioner of administration, the elder Roemer controlled the state budget and presided over the collection and dispersion of billions of dollars in revenues.

By the time he entered the governor’s race last year as a dark-horse candidate, Buddy Roemer had long since split politically from his father, who was convicted in 1980 of accepting a bribe from an FBI informant posing as an insurance executive in the federal sting operation known as Brilab. The younger Roemer called for a Louisiana revolution against the politics of the past. He racked up political capital by calling the state budget a “joke” and promising to “scrub” away wasteful and unnecessary spending. He picked on a variety of politically unpopular state programs as he talked about ways to cut the budget by $300 million. He almost made it sound easy.

Trailing in fifth place for most of the race, Roemer’s tough talk finally caught on in the fall. His candidacy was ignited by a series of newspaper endorsements across the state as he jumped into the lead in the last week of the campaign. An exhausted and out-foxed Edwards withdrew from the race after running second in the primary, and Roemer was declared the winner. Edwards then invited the governor-elect to put his own team in immediate control of the state budget. The revolution against the past was under way. Reformers looked eagerly toward the dismantling of the Long legacy in Louisiana.

But since getting his scrub brush on the budget last December, Roemer has found that it will take Some pretty strong soap to clean things up. He discovered immediately that the stain of red ink was much more pernicious than he thought during the campaign. His administrative team found bills going unpaid, dedicated funds being raided for general operational expenses, and barely enough cash to make payroll each week.

By the time he took office on March 15, Roemer was claiming, with some hyperbole, that the state faced a deficit of $2 billion — including accumulated shortfalls of $1.3 billion from the Treen and Edwards administrations. “The problems were much larger than we expected them to be,” said Chief of Staff Steve Cochran, an architect of the governor’s budget strategy.

Despite the surprises, Roemer hung tough on the need to break with Louisiana spending tradition. “Now is not the time to talk taxes, but rather is a once in a lifetime opportunity to debate essential spending levels and priorities,” Roemer said.

That debate was joined during three months of stormy committee meetings and floor wrangling over Roemer’s spending plans. Now, the eloquent governor’s heated rhetoric has been translated into the cold numbers of a budget document with his name on it.

Beyond the Rhetoric

How close did he come to achieving the idealistic goals he set out in his public statements? Roemer officials are putting an optimistic spin on the budget, but the imprint of fiscal reform on the new document is very faint. Roemer did manage to cut spending by $500 million. But he was also forced to raise over $500 million in taxes and fees to help retire the accumulated debt and bring the $7.9 billion budget into balance.

Where those cuts will be made is still unclear. Even Roemer admirers charge that the new budget is a very vague document which spells out few specifics. That ambiguity would have drawn severe criticism if Edwin Edwards had tried to foist it off on the legislature, but independent-minded legislators who might have protested were silent.

“The budget that we had this year was very general. It was not nearly as detailed as it should have been. There was not enough information . . . from a programmatic point of view,” said Mark Drennen, president of the Public Affairs Research Council, a leading voice for change in Louisiana. “A lot of those of us who wanted to cut the budget are getting the results that we wanted. But the process that we wanted to get there is not being used. We are relying on the good graces of the governor.”

Cochran says the bulk of spending reductions will come in the area of personnel — the budget calls for slicing the state’s 73,457 government jobs by 7,000 positions. Exactly what positions will be cut will be left up to those who run state agencies. “The best way to do it was to give them this mandate: ‘Here’s how much money you have to run your department,’” said Cochran. “We did try and provide as much flexibility for managers as we can.’”

The new budget eliminates few services outright — only two stale police troops, a number of driver’s license bureaus, and several miscellaneous state agencies will be closed. “We didn’t do away with any programs. We didn’t merge anything,” said state Representative Raymond Laborde, a member and former chairman of the House Appropriations Committee. “[Roemer] found out that the budget had been cut a lot already. The campaign rhetoric was gone.”

Hand-to-Hand Combat

Beyond the short-term efforts to deal with the current crisis, Roemer has made only halting first steps toward permanently redirecting the way Louisiana spends its money. In three critical areas, which account for well over 50 percent of state spending, he has had little success in achieving the goals which budget reformers have talked about for years.

Health Care. Programs and facilities which care for the poor and sick are a frequent battleground between populists and fiscal reformers. Health care and social services account for about a quarter of state spending annually, but such programs were virtually untouched by the budget.

While a demonstrable concern for the less fortunate is a legacy of the Huey Long years, his heirs have often used the system for less altruistic reasons. The poor often become pawns in a game of power politics: services are provided and then retracted in an attempt to mobilize large blocks of voters. A popular gambit of past governors confronted by a budget-cutting legislature was to close down a popular program such as kidney dialysis, knowing the outcry that would result.

Support for the poor has also served as a cover for actions which benefited business interests at the expense of taxpayers. For example, legislators have long resisted efforts to allow generic drugs to be prescribed for indigent patients covered by the Medicaid program. Their purported reason was concern for quality — but in reality many were motivated by the entreaties of pharmaceutical manufacturers interested in the high profits which name-brand drugs generate.

The Charity Hospital system is another good case in point. Louisiana operates a huge network of full-service health care institutions which provide free treatment for the state’s poor. The origins of the system can be traced back to colonial times, but its expansion began under Huey Long and has continued under populist governors that succeeded him. In recent years, as the Reagan administration has cut federal aid to the state, charity hospitals have been an important safety net for the working poor — individuals who have no private insurance but make too much money to qualify for Medicaid programs.

But political support for charity hospitals often stems not from the services they provide the poor, but from the jobs they provide constituents. Some legislators have resisted health care innovations, fearing that more efficient services would lead to layoffs in their districts.

Many Roemer supporters — especially conservatives and business interests — have used these flaws to whip up opposition to the charity hospitals, and to the human services program as a whole. They suggested that the sprawling Department of Health and Human Resources bureaucracy be targeted as a prime starting point for budget cuts. Roemer responded with a two-pronged proposal to close or shift control of several hospitals, and to privatize others on an experimental basis. Both plans failed.

Roemer proposed closing a charity hospital in Tangipahoa Parish. But the facility happened to be located in the district of the powerful chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, a key figure in Roomer’s effort to pass his legislative program. That senator exercised his considerable clout, and funding for the hospital reappeared in the final budget — albeit with a warning that the hospital had to increase its efficiency.

Roemer also wanted to turn another charity hospital in Lake Charles over to a regional governing board. But the governor backed away from the plan after opponents called it the first step towards withdrawing state support for the hospital.

The administration also had little luck in privatizing state services. Some Roemer backers argued that private firms could run charity hospitals and other facilities more efficiently than the state, but no legislation was passed to try the approach. “We got our butt handed to us on that,” admitted Cochran.

Higher Education. Louisiana operates a far-flung system of colleges and universities which often duplicate programs and dilute financial resources. But in Roemer’s first budget, funding for the higher education system came in for little scrutiny other than a failed attempt to merge all state campuses under one board. Roemer’s initial spending plan would have closed two junior colleges in Shreveport and New Orleans, but those terminations were revoked after some political maneuvering.

The future of higher education in Louisiana is now inextricably linked to a federal court order which calls for integrating state colleges and universities. Roemer apparently plans to use the ruling to revive his plan to consolidate all governing of higher education under one board. Once control is achieved, Roemer hopes to revamp funding for state campuses.

Elementary and Secondary Education. Roemer officials point to this area as their biggest success in restructuring the relationship between state and local government. Historically, Baton Rouge has provided most of Louisiana’s education spending, paying for a large percentage of teacher salaries as well as non-instructional items like school buses and food services.

Roemer’s initial budget completely eliminated state support for such items. He eventually agreed to fund them for one year at a slightly reduced level, after which responsibility for the services would shift to local school boards.

“Our fundamental belief is that an educational system ought to be done at a local level,” Cochran said. “I think we have made great strides in implementing this philosophy and having the budget reflect what we are trying to accomplish.”

Although local boards understand that they are on their own after this year, knowing that buses and food services are up to them and actually paying for them are two different things. “They are aware of it, but they say, ‘How are we going to do it? We don’t have the money,”’ state Representative Laborde said.

The Next Challenge

Roemer’s flair for the dramatic and tremendous self-confidence have raised new hope among budget reformers that he will be able to dismantle the worst of the Long legacy in Louisiana. But after his first major legislative tests, he has yet to repudiate that inheritance.

♦ Roemer shows no signs of diminishing the power of the executive branch. Indeed, he has asked for and received tremendous authority over fiscal matters, prompting comparisons in some quarters with the Kingfish himself.

♦ Roemer must still design a legislative package which restructures how state government provides human services. His attempts during the first session encountered tremendous political obstacles.

♦ To be sure, Roemer is confronting Louisiana’s tax system: a massive program to shift the burden of taxation from businesses to individuals was scheduled to be presented to a special session of the legislature in October. The proposed legislation would cut state sales taxes, raise personal income taxes, and gradually increase property taxes on homes valued at under $75,000. But passage will require a two-thirds vote from the legislature and support from voters in a statewide referendum, tentatively scheduled for December. That remains a dicey proposition.

So far, most veteran budget reformers are impressed with the quality of the administration’s effort to bring state spending under control. “What he has achieved in the short time in office has truly been remarkable,” said former state Representative Jock Scott, who fought a frustrating and ultimately losing battle to restructure the state budget during the Edwards administration.

Although Roemer has made great strides in his first seven months in office, he has yet to address some serious underlying issues of state budgetary policy. Nor has he staked out a middle ground between politicians who want to preserve the present inefficient system of human services at all costs and fiscal conservatives who have uncontrolled budget-slashing as their hidden agenda. Still to be answered by Roemer, in conjunction with the legislature, are such questions as:

Should we care for the indigent and treat the mentally and physically handicapped primarily through large institutions, or should we decentralize those functions and provide services at the community level?

Will turning services over to private companies compromise the quality of care and reduce the level of state commitment?

How can the state give all citizens an equal opportunity to attend college, but still allow some campuses to pursue more advanced missions such as primary research and education of gifted students? How many colleges do we actually need to get the most bang for our higher education buck?

If financing of elementary and secondary education is best provided at the local level, how do we ensure that poor parishes do not fall irretrievably behind more affluent urban areas?

How do we maximize revenues from the extraction of minerals — a depicting, non-renewable resource — without becoming overly dependent on this form of taxation as we have done in the past?

Buddy Roemer is in a unique position to force this debate. While he has clearly thrown in his lot with fiscal conservatives in state politics, he has paid at least lip service to the need for compassion and concern for the less fortunate. He has begun to address, if tentatively, some of the questions posed above.

But to negotiate successfully the tightrope between the populists and fiscal conservative elements in Louisiana, Roemer must commit much more of his political capital to the effort. Restructuring the budget is the most complex issue Roemer faces — and the most important issue to the future of the state. The real trial by fire of his governing skills is yet to commence.

Tags

Richard Baudouin

Richard Baudouin is editor of The Times of Acadiana in Lafayette, Louisiana. (1988)