This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 3, "Mint Juleps, Wisteria, and Queers." Find more from that issue here.

The young marine, dressed in civvies and thankful for the lift, got out of the car at the Fast Fare, glanced around carefully, and made his way quickly through the adjacent dirt parking lot to the unmarked building sitting unobtrusively off a major thoroughfare in town near the base. Inside, he relaxed, grateful he had once more made it through the parking lot without seeing an Onslow County Sheriff's car. Now he could enjoy himself for a few hours — at least until he’d have to leave and the fear would return again.

Two hours later, the word passed through the bar: they're there again. Military personnel shouldn’t go outside.

Closing time. The sheriff’s car remained. Brandy Alexander — legal name: Danny Leonard — made up his mind. He wasn’t going to let the dozens of Marines in his bar run the risk of court-martial. He asked friends with vans to pull up to the bar out of sight of the sheriff’s car. He herded the Marines in, saw them off, and closed for the night.

That evening five years ago was the beginning of a long, hard fight for Leonard and soldiers at the Friends Lounge near Camp Lejeune Marine Base in Jacksonville, North Carolina. Because the lounge is the only gay bar in the country that is officially off-limits for military personnel, Marines who are caught there find their careers abruptly jeopardized.

Bars have always been an important meeting place for gays and lesbians in the South, one of the few public places they could go to dance and meet others and relax in safety. Now, at the Friends Lounge, gays have discovered that a place that serves as the center of their social lives also offers them a chance to organize politically and create a supportive family of friends.

Led by Leonard, customers resisted the military campaign of harassment — and won temporary victory. For almost two years, gay soldiers who frequented the bar enjoyed a tenuous peace. Business thrived. On Saturday nights, more than 200 people came through the door, up from the 25 or so who braved being seen when harassment by military officials was at its peak.

Then, on August 5, Naval Investigative Service officers — chauffeured by an Onslow County Sheriff’s deputy — resumed their campaign of harassment, stopping customers who looked like Marines going in and out of Friends Lounge.

The officers stopped at least two carloads of bar patrons and took two men to the sheriff’s office. One, a civilian, was released. The other, a Marine with only 11 days left in his enlistment, was detained.

The gay community in Jacksonville is raising hell, rallying around Leonard and the Friends Lounge. Many say the sheriff should be able to find better things to do than harassing soldiers in a city with the eighth highest crime rate in the nation.

“We’re making lots of contact with people on the base, legislative people, and city council people," said local gay activist Don Davis. “There is a new commanding general on base, and that may or may not have something to do with this.”

“Now that it’s started happening again, I can use all the help I can get,” Leonard said. “Not so much for me — I can always go back into hair — but for the military boys. Nobody knows the kind of bullshit military gay people have to put up with.”

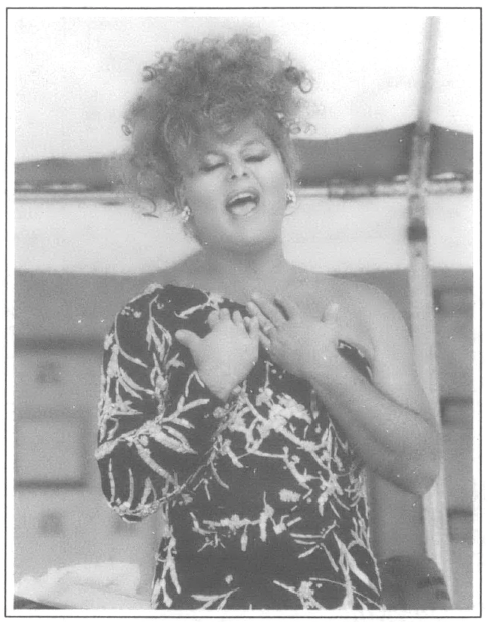

Leonard, a popular female impersonator throughout the South for 24 years, has become one of the best known gay activists in the region. He has helped organize benefits that have raised more than $350,000 to support people with AIDS — more than the entire state of North Carolina has contributed to fight the epidemic.

Leonard was appearing at the Miss Gay America Pageant in Charlotte, North Carolina in 1982 when the owner of the Friends Lounge asked if he wanted to buy it. He did — not realizing the consequences of operating a gay bar next to the largest Marine base in the world.

In the Brig

In 1983, the harassment really started.

The sheriff’s department and MPs decided they’d start something called a Community Service Patrol. They’d put Naval Investigative Service people in sheriff’s cars, drive around to off-limits establishments, look for military stickers on cars, and turn in sticker identification to base officers. If a Marine’s car was reported parked at my place, their pay was busted, their rank was reduced, and they’d be investigated for being gay. They could get up to seven years in prison and dishonorable discharge.

I raised so much hell with them about coming onto my property that they started parking at the Fast Fare. If they saw any of the boys walking off my property, they’d ask for a military ID, turn them over to NIS, and they’d be put in the brig.

This just went on and on and on. One Saturday night, the sheriff’s car was there, and I got on the mike and told anybody in the military to stay. We had about 125 boys stay in the bar that night.

We’ve had people crawl out in the woods to change clothes and leave. We’ve put them in car trunks. We’ve put them in vans.

One boy who was caught had been fighting for his country for three years and had only two months left. Another man had served almost 30 years and wasn’t even gay. They pulled him on his way off my property, court-martialed him, kicked him out of the service, and took all his benefits just because he was in an off-limits place.

One night, five boys walked off my property toward the Fast Fare. The people in the sheriff’s car stopped them. I walked out and asked why they were bothering my customers. They told me to get the hell back or they’d bust me, too.

I finally told my military customers to keep their cars off my property, to call the bar and we’d go get them.

I called the N.C. Human Rights Fund and it wasn’t something they could help with. I called the ACLU and Lambda Legal Defense Fund and kept getting the run-around. I couldn’t afford to hire a lawyer.

“I Couldn’t Leave”

It got so bad. I wrote a letter to the county commissioners, to the sheriff, to the newspapers and TV and radio stations in Jacksonville, New Bern, and Wilmington. Two radio stations and three TV stations interviewed me.

After the publicity, they backed off and left me alone for almost a year. Then election time came and they started again sporadically, but it wasn’t as serious.

The media have been on my side. They’ve been very professional. They couldn’t figure out why we had been singled out for discrimination. We’ve donated $2,000 to the Beirut Memorial Fund — more than any other private business in town. We’ve done public benefits and Christmas Cheer and Toys for Tots. We raised almost $4,000 in October for AIDS.

The media asked why the sheriff was using money from Onslow County taxpayers to monitor Marines going into and out of a bar. And the sheriff stuttered something about it being his department’s job to help out the military.

When I was doing drag in Florida in 1964, we were pulled out of bars and beaten by cops with billy clubs. I’ve been put in jail probably 50 times. They’d pull paddy wagons up and put all the female impersonators and owners in, then fine us for being in women’s clothes. They used to make us strip down, and we had to have three items of male clothing. So we’d wear three pairs of jockey shorts under our dresses.

What was going on in Jacksonville reminded me of that. Bars have changed an awful lot since then. There are more of them, they’re more open. I don’t want to see these kids go through what I went through.

I’ve withstood this because — well, I wish you could meet these boys. They’re proud to be Marines, proud to be fighting for their country.

I couldn’t leave. You can’t know how it is to get a phone call and the person says, ‘Four years ago, I came to your bar and I want you to know I love you.’ When these kids come back home, they have a place to go. There’s no way I could turn my back on them.

Tags

Don King

Don King is news editor of The Front Page, a newspaper for gay men and lesbians in North and South Carolina. (1988)