Almost Broke, West Virginia

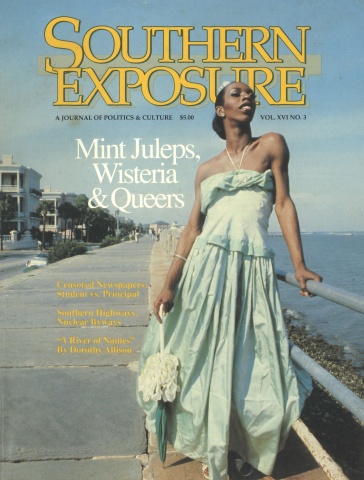

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 3, "Mint Juleps, Wisteria, and Queers." Find more from that issue here.

West Virginia never had much fat to spare. So when Ronald Reagan first started chopping federal dollars from state budgets in 1981, state politicians went scrambling. West Virginia’s entire state budget was only $2.2 billion, so that first $63 million whack sliced deep into existing state programs.

Some states could absorb those first cuts easily. With large reserves, they could live off their fat while they decided what to do. States with big tax bases and comparatively wealthy populations could raise state taxes without undue hardship. Not West Virginia. It had a small tax base and no financial cushion. Seven years and many federal cuts later, the state is awash in red ink.

“In many instances, we have not been able to adjust,” said Assistant State Treasurer Arnold Margolin. “We’ve simply had to discontinue programs, forgo building projects, not buy the books for local libraries. You just don’t buy the books. You don’t build the sewer. You don’t repair the bridge. You don’t have the financial aid, so someone doesn’t go to college. How do you quantify that?”

Between 1981 and 1987, federal support to West Virginia dropped from 32 percent of the state budget to 26 percent. If the percentage had stayed the same, Margolin said, West Virginia would have received $200 million more federal dollars in 1987 alone.

Two hundred million a year isn’t much in federal terms. It would buy one MX missile. But $200 million is approximately six percent of the entire West Virginia budget, enough to spell the difference between red or black ink for a small rural state.

This year, signs of financial distress crop up almost every week in state newspapers:

♦ The public schools sued the state for falling $72 million behind in support payments. Without that money, schools struggled to pay teachers and buy basic supplies.

♦ In June, the state owed health care providers over $100 million in Medicaid payments. Hospitals and doctors now routinely refuse to take state insurance and ask state employees to pay up front.

♦ People who sold the state items like office equipment and toilet paper or provided legal services in 1987 still haven’t been paid. The legislature recently passed a law that says the state has a “moral obligation” to pay them.

♦ Last spring, the highway commissioner warned that about 40 percent of the state’s bridges are unsafe, and the state can’t afford to fix them.

In all, legislative leaders estimate that the state owed between $240 million and $400 million in outstanding bills at the end of June. “If we were a business, we’d be declaring Chapter 11 bankruptcy,” said George Farley, finance chairman of the House of Delegates.

Problem? What Problem?

In the midst of all this alarming news, Republican governor Arch Moore and his lieutenants constantly paint rosy pictures of the state budget. The governor’s re-election ads proclaim that the state has “turned the comer” and is recovering. In July, Moore actually told the press that the state had finished fiscal year 1988 in the black. Astounded, the auditor and legislative leaders immediately contradicted him, citing evidence of a mounting economic crisis.

Nobody says federal cuts caused all of West Virginia’s problems. Coal employment, the foundation of the state economy, has been in a slump since the late 1970s. The state has lost an estimated 62,000 jobs in mining and manufacturing, and most of the 34,000 jobs it has gained have been low-paying service jobs. In 1985, a huge flood hit the state, disrupting state services and small businesses in 29 counties.

Democratic state leaders do say the state could have weathered those setbacks if the federal government had not also pulled the plug on them. “Without the federal cuts, our nose would not be where it is now, underwater,” Farley said.

Republicans disagree. “There are no federal cuts,” Finance and Administration Commissioner John McCuskey said flatly. “West Virginia actually received more federal dollars in 1987 than it got in 1981. So how can anybody talk about federal cuts?”

Assistant Treasurer Margolin, the Democrat who held McCuskey’s office from 1976 to 1984, said his successor is mixing apples and oranges. Yes, the actual number of federal dollars to the state has gone up, Margolin said. But after seven years of inflation, the federal aid West Virginia received in fiscal year 1987 was actually worth 16 percent less than the money the state received in fiscal year 1980.

Moreover, Margolin said overall federal dollars have increased because the worsening economy has forced more people to sign up for public assistance. The new federal dollars are due to sharp increases in programs like food stamps, Medicaid, and Aid to Families with Dependent Children accounts; so the increase is actually one more distress signal.

Margolin noted that those additional public assistance dollars actually cost the state money. The state must put up matching dollars to get the federal aid, but the federal dollars go to clients or doctors and other care providers, not the state. So the state loses money it could have used to ease the strain on other state programs.

Unable to replace direct federal cuts, the state has significantly reduced or eliminated many essential services for children, the elderly, the mentally ill, and the disabled. Federal funds for badly needed sewers are gone. Local health, library, and elderly programs have also been severely reduced.

Survival of the Richest

“I think West Virginia is part of a handful of states that are more dependent on a federal-state partnership, to continue the strides that we made in the ’60s and ’70s,” said Margolin. “The rules of that partnership changed dramatically in 1980, and have continued to this day. And we’ve had a very difficult time under the new rules.”

Farley, the House finance chairman, said the formula for getting federal dollars discriminates against less wealthy states. “West Virginia can’t even afford to get all the federal dollars we’re entitled to, because we can’t afford to put up all the match.” Under the rules of Reagan’s new federalism, West Virginia has to pay the same match as a wealthy state does, even though it has less money and needs the federal aid more. Medicaid is now the only major federal program based on a state’s ability to pay.

“That’s the real problem I see in the new federal-state relationship,” said Margolin. “Many of their policies are based on the mistaken assumption that every state has the same ability to pay. Maybe it’s easier at the federal level to do it uniformly, but it causes inequities to continue and makes it harder for poor states to catch up.”

Again, state Republican leaders deny the problem exists. “To my knowledge, West Virginia is getting just about every federal dollar it can get,” said McCuskey.

“That’s an amazing statement,” Farley said, pointing out that the state couldn’t even afford to match the Medicaid dollars it needed to pay hospital bills last spring. The state has actually contracted with two consulting firms to find ways to get more federal dollars.

Nobody from the Reagan administration has expressed concern about West Virginia’s difficulties, Farley said. “They’ve never offered to help and never even acknowledged that problems exist,” he said. “But maybe it’s awkward for them to offer help when the governor says the problems don’t exist.”

Washington’s silence frustrates many who remember the War on Poverty and the federal commitment to Appalachia during the Kennedy-Johnson years. “Sometimes I think maybe we should announce a communist insurgency out here, so they’d pay attention to what’s happening to us,” said Perry Bryant of the West Virginia Education Association. “It’s pretty tough watching Reagan push Congress to send hundreds of millions to Central America’s military, knowing what’s happening to us. What about the problems in our country? What about us?”

Problems have trickled down until the local level is swamped. In 1986, Reagan cut off federal revenue sharing funds. Many West Virginia counties depended on those funds for as much as a third of their budgets, using the money to pay for basic services like police, fire, ambulance, prenatal care, nutrition, and libraries. In fiscal year 1988, the state doled out leftover interest on the funds, but this year the well is dry.

Ironically, Richard Nixon established revenue sharing back in 1972 to send federal dollars back to the states. Tax dollars came from the states, he said, so the feds should send back more dollars, with fewer strings. Reagan has reversed that relationship. Today it’s less support, more strings.

“It really kills me to hear the feds talk like that money belongs to them, like they’d been giving it to us as charity,” said Perry Bryant. “But it was always our tax money. Now we’re taxed higher, and they’ve just decided to keep it, while we hang out to dry.”

More Taxes, Less Service

Reagan took office promising to cut federal taxes as he withdrew aid. Most Americans never got the tax cuts. Instead, the money was absorbed by interest on the national debt, huge federal corporate tax breaks, and the military budget. As a result, most West Virginians now pay higher federal and state taxes and get less service than they did before Reagan was elected.

Nobody can say West Virginia hasn’t tried to cope. Since 1981, the state’s tax effort has increased to 47 percent of the gross state product, according to House finance figures. Although West Virginians rank 49th in per capita income, they now pay taxes slightly above the national average.

Most other states have been in financial hot water at some time since the early ’80s, especially energy and farm states. Twenty-nine states ended fiscal year 1987 with general fund reserves smaller than the five percent considered prudent, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). Small buffers leave states vulnerable to unexpected downswings. Fifteen states had less than one percent reserves. Eight were Southern states: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Texas, and West Virginia.

“Without the federal support, what happens is, you become so much more vulnerable to an economic shock that you previously could absorb or weather,” Margolin said. “Now it’s much harder to deal with any kind of unforeseen economic downturn.”

As West Virginia lost federal funds and the coal economy faltered, courts also ordered the state to improve its prison, education, health, and mental health systems. To cope, West Virginia raised taxes, slapped on spending freezes and cuts, and reduced or eliminated services. According to the NCSL, 21 other states also substantially raised taxes in 1982, the first year after federal cuts hit the states. In 1983, more than two-thirds of the states raised at least one tax, for a record $7.5 billion in new state taxes.

West Virginia also conducted a statewide property reappraisal which still hasn’t gone on the books. Taxpayer groups say it would raise residential taxes and lower corporate taxes.

Financial desperation has provided a favorable breeding ground for other “solutions” likely to shift the load onto the average citizen: (1) lowering business taxes, and (2) kicking the problem downstairs to local government.

Business lobbyists traditionally argue that lower business taxes attract new business, despite studies to the contrary. In 1987, desperate for new jobs, West Virginia included some rather large loopholes in its new business tax law. The changeover cost the state about $30 million in fiscal year 1988, providing more incentive to kick problems downstairs to local government whenever possible.

The Locals Get Clobbered

So far, West Virginia has forced local government to pay for items like orphan roads, state prisoners, sophisticated computer systems, and certain property tax reappraisal costs. The state has withheld tax money that belongs to the counties, and owes tens of thousands of dollars to some counties for items like the rental of magistrate offices.

After losing revenue sharing, many West Virginia counties can’t pay all their employees, much less pick up the tab for state or federal responsibilities. It is not the best atmosphere in which to raise local fees or taxes. Still, faced with the loss of basic services, local leaders must either raise money or cut programs people need and want.

In several counties, sheriffs or assessors have sued county commissioners for cutting their budgets. They contend that, since the law requires them to perform certain duties, commissioners must give them enough money to do so. Enough money isn’t there. So commissioners have cut items they have no legal responsibility to fund, like health departments and libraries, to pay for mandated services like law enforcement.

“After the fat’s gone, you cut into muscle, and that’s when it gets tough,” said Gene Elkins, executive director of the West Virginia Association of County Officials. Observers predict that within a few years, both local and state governments will be under all manner of court orders they can’t afford to carry out.

Faced with this no-win dilemma, an unusual number of experienced local leaders decided not to run for office this year. “They say it’s just not worth the hassle,” said Elkins.

Clay County Commissioner Don Samples decided not to run for re-election when the county lost its federal revenue sharing. “The voters don’t blame the federal government,” he said. “They just blame whoever’s in office.”

Some local leaders, desperate for money, are now more open to options they wouldn’t consider before. In rural Tucker County, for instance, county commissioners faced with the loss of their emergency dispatch service voted to allow an Alabama county to dump hundreds of thousands of tons of out-of-state garbage in the county landfill, for a fee.

Angry Tucker County citizens forced a cancellation of the contract. Now the commissioners still have to find money to fund the ambulance dispatch service. And the health department. And the sheriff. And the library. And the senior citizens programs. With little hope of help from the state.

A Vicious Circle

Barbara Bayes, director of the Charleston Legal Aid Society, can list federal policy changes since 1981 that have made it harder for low-income people to get off welfare. The feds now take your medical card soon after you start a job, she says. They have made it tougher to get child care while you work. Drastic cuts in low-cost housing. Drastic reductions in student loans. And so forth.

Such policies have hurt the state budget too. Every person on public assistance costs the state money. When it’s harder for people to get back on their feet, it’s harder for the state to get back on its feet.

Even the ripple effect of Reagan’s federal policies has trapped states like West Virginia in a downward spiral:

♦ When federal dollars go down, state borrowing goes up. High unemployment forced West Virginia to borrow almost $250 million from the feds to cover unemployment checks. The state sold bonds to pay the feds back.

♦ Delays cost money. After losing Appalachian highway funds and sewer funds, West Virginians watched with dismay as construction costs soared. “By the time we get the money to build the sewers, we won’t be able to afford them,” Margolin said.

♦ With less money to invest, the state generates less interest on state funds. In 1986, Margolin oversaw a rate of return of 13 percent on state funds. Now he gets only about eight percent.

♦ As people move away in search of jobs, federal aid based on population drops even further. West Virginia has lost almost 2.7 percent of its population since 1980, the biggest loss in the nation. As the tax base shrinks, fewer children enroll in school, and the state is eligible for fewer federal education dollars. The vicious circle keeps rolling.

Republicans like Commissioner McCuskey say negative thinking is hurting the state. “The governor didn’t make up those 34,000 [new] jobs,” he said. “Everybody isn’t leaving the state on the hillbilly highway. Sure, they’re not coal mining jobs, but service industry jobs are still good jobs. And that’s the way it’s going in the whole country, not just West Virginia.”

Perry Bryant of the education association said he longs for more reason to think positively. “There was such a feeling of hope here in the ’60s and ’70s. If you didn’t have much, you still felt you could do something for yourself if you worked hard enough. It’s not like that now, but I hope it will be again. I want that feeling back.”

Meanwhile, history repeats itself. In the ’40s and ’50s, millions of Appalachian people had to leave home to find jobs in Northern cities. People joked about “the three R’s: readin’, writin’, and the road to Akron.” On weekends, thousands of West Virginians traveled south to go home to the mountains they loved.

Nothing has changed about the way West Virginians love their state. Today the newspapers report that on Fridays, thousands of West Virginians travel north from Southern cities like Charlotte, going home for the weekend.

Tags

Kate Long

Kate Long, a West Virginia native, is president of the board and a lobbyist for West Virginia Citizen Action Group. She is the author of Johnny's Such a Bright Boy, What a Shame He's Retarded (Houghton-Mifflin, 1977). (1984)