This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 2, "On the Map: New Views of the Early South." Find more from that issue here.

In 1502, on his fourth and last voyage to the West, Christopher Columbus waylaid a Mayan trading canoe carrying an old man. The European admiral still believed he was near the Indies, and he always described such local inhabitants as Indians — a term which has stuck ever since. The Mayan, whose geographical outlook was very different, knew exactly where he was and drew charts of the Honduran Coast to prove it.

As subsequent foreign explorers probed the New World, time and again they called upon the expertise of indigenous mapmakers in an effort to get the lay of the land. In 1703, two centuries after Columbus, Baron De Lahontan told how northeastern Indians kept maps “drawn upon the Rind of your Birch Tree; and when the Old Men hold a Council about War or Hunting, they’re always sure to consult them.”

By this time, after generations of contact, some Indians had adopted certain conventions of Old World mapmaking, such as the European practice of putting North at the top of the map. According to the Frenchman:

they draw the most exact Maps imaginable of the Countries they’re acquainted with, for there’s nothing wanting in them but the Longitude and Latitude of Places. They set down the True North according to the Pole Star; the Ports, Harbours, Rivers, Creeks and Coasts of the Lakes; the Roads, Mountains, Wood, Marshes, Meadows, etc. counting the distances by Journeys and Half-Journeys of the Warriors and allowing every Journey Five Leagues.

What was true elsewhere in North America can now be documented explicitly in the South. Little-known records make clear that the ability to draw maps was widespread among Southern Indians during the colonial era. What’s more, the few surviving copies of Indian maps from that period also provide insights into how native Southerners organized their societies and perceived their world. They were not the separate and peripheral “tribes” conceptualized by European colonizers and perpetuated over the generations in our history books and popular culture.

Nicety and False Reports

Early evidence for the mental maps of Southern Indians was noted by the English colonists who settled at Jamestown in 1607. They inform us that local members of Chief Powhatan’s confederacy produced maps on several occasions. One simple chart showed the course of the James River, while a more ambitious map depicted their place at the center of a flat world, with England represented by a pile of sticks near the edge.

During ensuing years, early colonizers found native Southerners to be proficient cartographers whose geographical knowledge greatly expedited the first European explorations of the region. Only rarely, however, did the newcomers express any interest in how the Indians viewed the world; their curiosity generally was limited to immediate practical matters, such as the locations of rivers, paths, and settlements (not to mention possible mines). When entering totally unfamiliar terrain, these geographical pointers from the Indians proved invaluable to hundreds of Spanish, English, and French explorers seeking new lands to exploit.

“They will draw Maps very exactly of all the Rivers, Towns, Mountains and Roads, or what you shall enquire of them,” reported John Lawson, who travelled through the Carolinas at the start of the 18th century. “These Maps they will draw in the Ashes of the Fire, and sometimes upon a Mat or piece of Bark. I have put a Pen and Ink into a Savage’s Hand,” Lawson wrote, “and he has drawn me the Rivers, Bays, and other Parts of a Country, which afterwards I have found to agree with a great deal of Nicety.”

“But you must be very much in their Favor,” Lawson added, “otherwise they will never make these Discoveries to you, especially if it be in their own Quarters.” He realized the Indians were quite clear about the value of geographic information to newcomers, so they sometimes provided false reports or withheld significant details. “And as for Mines of Silver and other Metals,” Lawson concluded:

Now, say they, if we should discover these Minerals to the English, they would settle at or near these Mountains, and bereave us of the best Hunting- Quarters we have, as they have already done wherever they have inhabited; so by that means we shall be driven to some unknown Country, to live, hunt, and get our Bread in. These are the Reasons that the Savages give for not making known what they are acquainted withal of that Nature.

But on the whole, geographically uninformed Europeans were seldom disappointed in their hundreds of requests for Indian maps of the Southern terrain. For several centuries, information imparted by means of ephemeral charts scratched in the sand, sketched with charcoal on bark, or painted on deerskin, was incorporated directly into European colonial maps, usually enhancing their accuracy.

“I have not rested satisfied with the verbal Discretion of the Country from the Indians,” Governor James Glen of South Carolina wrote in 1754, “but have often made them trace the Rivers on the floor with Chalk, and also on Paper.” Impressed by such drawings, Glen added patronizingly, “it is surprizing how near they approach to our best Maps.”

One Indian mapmaking tradition of the colonial period, as described by Lawson, Glen, and others, did indeed involve approximations of European maps, as geographic information became another commodity in intercultural trade, along with deerskins, ginseng roots, and Indian slaves. In fact, it was an Indian slave who provided one of the most intriguing examples of this kind of detailed, geographic travel map.

Lamhatty’s Journey

In 1708 Colonel John Walker of Virginia sent the governor a map drawn by a Towasa Indian named Lamhatty. Though the original is lost, colonial officials preserved a contemporary copy of the map which still survives in the Virginia Historical Society, along with two accompanying accounts by Walker and Robert Beverley, a prominent English settler. (See map, page 25.) From these shreds of evidence, a strange story emerges.

Following the Christmas holidays of 1707 a single Indian, “naked & unarmed,” approached the frontier home of Andrew Clark, an English settler on the Mattaponi River in eastern Virginia. According to the letters, he appeared there on Saturday, January 3, “in very bad weather.” Unsure of his whereabouts, the wanderer had entered the upper reaches of King and Queen County, north of the new capitol at Williamsburg.

More pitiful than dangerous, the stranger willingly “surendered himself to the people.” Nevertheless, they were frightened by his sudden appearance and “Seized upon him violently & tyed him tho’ he made no manner of Resistance but shed tears & shewed them how his hands were galled and swelled by being tyed before; where upon they used him gentler & tyed the string onely by one arme,” as they set out downstream with their captive.

On Sunday they reached the estate of Colonel Walker, who took matters into Photo from Ashmolean Museum, Oxford his own hands. Reporting the Indian’s presence to the governor in Williamsburg, Walker wrote that, “at first I put him in irons, and would have brought him to yor Honr, but the extremity of the weather prevented any passage over Yorke River. After three dayes, finding him of a seeming good humour, I let him at liberty about the house where he still continues.” Perhaps seeing an opportunity for an additional slave or a backcountry guide, Walker concluded, “he seems very desirous to stay, if I might have yor: Honrs: leave to keep him.”

Meanwhile, Walker reported, the newcomer “at all times seemd verey inclinable to be understood, and was verey forward to talk.” Though his language was unfamiliar to local translators, bits and pieces of his story got through the communication barrier and can be linked with what is known of events taking place at this time.

The young man was Lamhatty, age 26, a Towasa Indian from the Gulf Coast region of north Florida. His home had been just above the fall line on the Chippola River, between modern-day Panama City and Tallahassee. He had been south to the coast and seen the Gulf of Mexico, stretching like a great salt lake, “whose waves he describes to tumble and roar like a sea.”

Lamhatty, it appears, was one of several thousand local Indian inhabitants who fell victim to the fierce slave wars being sponsored by the English. Within a generation of settling Carolina in 1670, Englishmen began leading raids against Spanish missions in the Apalachee region of northwest Florida. The newcomers realized they could export enslaved Indians (more valuable elsewhere, since they could not escape home) and use the proceeds to import black slaves from the West Indies or Africa. By attacking the Spanish missions, the English hoped to cripple the Catholic powers and their Indian allies along the Gulf Coast, create new prospects for Western expansion, and secure profitable slaves all at the same time.

The strategy worked. Colonel James Moore of South Carolina and his private army destroyed several missions in northern Florida in 1703 and 1704, killing or enslaving several thousand Indians. Moore later boasted that these brutal forays cost him fewer than 20 men “and without one Penny charge to the Publick.”

Indian refugees from the missions fled to nearby Towasa villages, but before long these towns also came under attack from Creek Indians allied with the English. Lamhatty was among those taken captive in the spring of 1707 and bound with rawhide cords.

The map Lamhatty drew for Walker details his remarkable journey as a slave, covering more than 600 miles in nine months. During his captivity he was first taken to a number of Creek towns indicated on the map “where they made him worke in the ground between 3 & 4 months.”

Eventually, Lamhatty was traded by his Creek captors to one of the bands of Shawnees living on the upper Savannah River. He traveled north with a small group made up of “6 men 2 women & 3 children, he continewed with them about 6 weeks, & they pitched thier Camp on the branches of Rapahan: River where they pierce the mountains.” Then on Christmas day, 1707, “he ran away from them” and headed east and south until he reached the English settlements on the Mattaponi River, where frightened settlers bound him again.

Lamhatty was not alone in his fate. Others from his village were probably among the Indian slaves brought into Charleston (then called Charlestown) by the Savannahs in 1707, and some of them may even have been sold into Virginia. According to a postscript written by Robert Beverley, “some of his Country folks were found servants” in the area, and after that Lamhatty himself “was sometimes ill used by Walker.” As the winter continued, Lamhatty soon “became very melancholly after fasting & crying several days together sometimes useing little Conjuration.” Finally, “when warme weather came he went away & was never more heard of,” leaving only his map behind.

The surviving copy of his map provides a rare personal glimpse into the colonial South nearly three centuries ago. Lamhatty displayed a knack for cartography, although his detailed geographical knowledge seems to have been limited to the Gulf Coast region where he grew up. His names and locations for rivers seem accurate in the southern reaches but become progressively distorted further north. While being led into the interior, he crossed rivers that he mistakenly equated with those flowing through Towasa territory, but such errors are understandable for a disoriented prisoner in unfamiliar country. Even his imperfect knowledge undoubtedly exceeded that held by Colonel Walker and others in Virginia.

The British Are Square

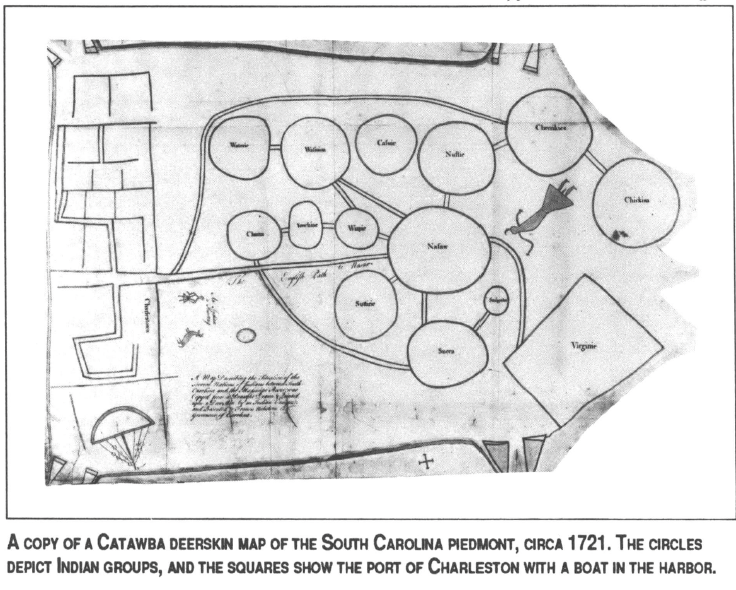

In contrast to Lamhatty’s personal depiction, drawn in response to English inquiries while he was in servitude, consider several extraordinary maps created two decades later and preserved by Francis Nicholson, Governor of South Carolina from 1721 to 1725. They were marked out on deerskin, and the apparent authors were a Catawba Indian from the South Carolina piedmont and a Chickasaw cartographer from what is now northern Mississippi.

Together with several similar maps from the same era, they represent a second, more independent Indian mapmaking tradition. Each provides a schematic rendering that shows relative positions and important interconnections for an informed mapreader — much the way bus or subway diagrams condense complex information into a limited space for city dwellers who know roughly where they want to go.

As was customary upon the appointment of a new colonial governor, Indian leaders from each of the major tribes were summoned to Charleston in 1721 to meet Nicholson. Among those invited were Creeks, Cherokees, and Catawbas: “A Head man out of each Town of each Nation to come down.” The Catawbas were a loose confederation of Siouan-speaking peoples settled near one another for protection in the South Carolina piedmont.

Nicholson probably took this opportunity to solicit a map, painted on deerskin, from a leader of one of the small Catawba groups. The original chart is lost, but two similar copies survive in London, drawn in red ink on paper cut in the shape of a deerskin. At the comers are pairs of triangles, presumably representing deer hooves, and there are several striking features, such as a man with a musket facing a buck, captioned “An Indian a Hunting.”

The central features are 13 circles labeled with Indian names and connected by an intricate network of double lines representing paths. Along the left side of the map is “Charlestown” with a boat in harbor, pennants flying. (Could it be the ship on which Nicholson had just arrived?) The distinctive grid may represent the rectangular street pattern of Charleston, or the low-country rice fields and irrigation channels then under construction, or both. Clearly the Indians associated straight lines and square comers with the newly arrived English, for in the lower right comer is a large rectangle marked “Virginie.”

By manipulating distance the mapmaker suggested the proper spatial ordering of map elements within the irregular confines of a deerskin, conveying a great deal of information regarding the Siouan groups and their surroundings. He showed that upon leaving Charleston, a separate trail branched off to the west, going beyond the piedmont groups to the Cherokees in southern Appalachia and beyond them to the Chickasaws in northern Mississippi. But he gave disproportionate space to the Catawba groups, almost like a larger blow-up in the midst of a small-scale regional map.

Such enlargement of the piedmont region suggests a Catawba-centered worldview, similar to modem caricature maps of “A New Yorker’s View of America” or “The World as Seen from Texas.” But it also underscores the importance of the Catawbas at the center of a regional trading network with numerous towns and trails familiar to the mapmaker.

He highlighted, with a large central circle, the significance attached to Nasaw (or “Nauvasa”), a principal town linked to the English in South Carolina and Virginia by direct trading paths. In 1728 William Byrd, traveling from Virginia, noted in his diary that after leaving Crane Creek, North Carolina, “About three-score Miles more bring you to the first Town of the Catawbas, call’d Nauvasa, situated on the banks of Santee river. Besides this Town there are five Others belonging to the same Nation, lying all on the same Stream, within a Distance of 20 miles.”

A Cacique Composite

Sometime during his brief tenure as governor, Nicholson received another Indian chart on a far grander scale — the Chickasaw deerskin map shown on the opposite page. This map, with its extraordinarily comprehensive view of the “Greater Southeast,” was drafted by a Chickasaw headman who probably had access to information accumulated by other tribe members. In other words, the great breadth of geographical knowledge indicated by this map, ranging as it does from Texas and Kansas in the west to New York and Florida in the east, may represent the collective knowledge of the Chickasaws in 1723, even if no individual Chickasaw had ever travelled so widely.

Such maps, drawn by caciques or headmen, can provide insights into the ways Southern Indians perceived their environment. They depict self-contained and ethnocentric worlds. Rivers arise and flow to their outlet within the confines of the maps, and paths end at the most distant villages or tribal domains. In each case, the cartographer has placed his native group near the map center with paths radiating outward from the focus of attention in a concentric, hierarchical organization of social space. The mapmaker’s village or tribe occupies the exclusive innermost position, while all others are relegated to an outlying ring. (This is not unlike American world maps of today, which are always oriented to place the United States in the upper center.)

The single most widely shared feature of early Southern Indian maps, however, is the use of circles to represent human social groups. In this context, the basic symbol of the circle probably represents the social cohesion of the group, mirroring the village plan common to many Southern native societies of the period. The Catawba mapmaker expanded the metaphor of the social circle when he drew a rectangular grid plan of Charleston and a square representing Virginia.

This dichotomy carried the clear message that diverse Indian groups were alike in being circular people, in contrast to the square English. Other symbolic oppositions, either implied or explicit, occur throughout these maps. In the concentric structure of some maps, we see an inherent opposition between we and they, the center and the fringes of the world. In other cases color draws the contrast, as in the use of black paint to indicate allies and red to identify enemies, or continuous trails to note peaceful trade and “broken” paths to signify war.

By recognizing and attempting to interpret the symbolic content of the maps, we begin to understand that they are indeed political documents, graphic depictions of the balance of power among Southern Indians. The visual messages encoded on these maps are still only partially decipherable, because our ignorance of this lost world remains so great. But, with time, we may yet appreciate more fully these few remarkable documents by native Southerners and the complex vision of the region that they contain.