This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 2, "On the Map: New Views of the Early South." Find more from that issue here.

The boat moved steadily in freezing rain through the waters of the Pamlico River in eastern North Carolina. Etles Henries Jr. held the helm and craned his neck out of the pilothouse to see how Jimmy Linson was doing with the nets. It was an icy cold Sunday in January with record low temperatures on the coast.

You couldn’t pay Henries and Linson to trade their lives for landlocked security.

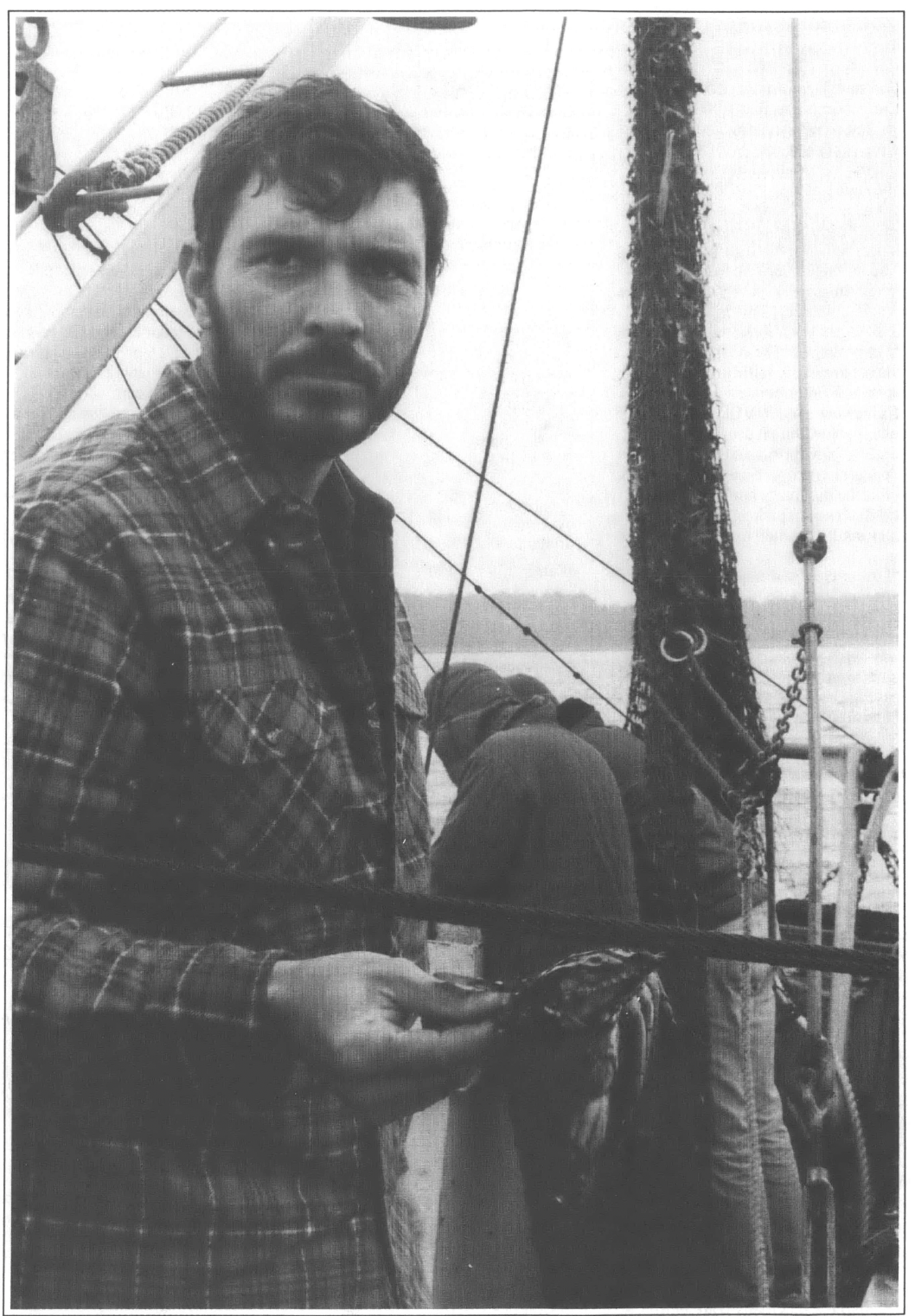

“Fishing gets in your damn blood,” Linson said. “After it’s all over you get in a warm spot and get thawed out a bit and laugh about it.” He wears a paint-spattered, olive green, quilted jumpsuit, an olive hat with furry earflaps, and white rubber boots. The crow’s-feet around the deep-set blue eyes in his full face crinkle when he grins. “Not fishing drives you up the wall,” Linson said, gesturing with his pipe.

But that day they didn’t catch much. A flounder. A baby menhaden, dead — with one of those red sores that plague almost every species in the estuary.

“It looks like cancer,” Linson said. “You see a fish swimming in a circle. You look at its belly with the guts hanging out and it’s still fighting for its life. It’s like watching someone laying down in the country to clean up its act. in bed to die.”

Each dead fish Linson finds is like hearing his own death knell. He loves his work but may have no choice but to leave it. He has a family to feed and a mortgage to meet, and he can’t survive if the fishing and crabbing he does on the Pamlico gets much worse. Last summer the catch was down by a third, and more than half the commercial fishers went out of business. Linson works as a part-time security guard and chops wood on the side as it is.

“Jimmy is just hanging on by the seat of his britches,” said Henries, who runs the crab-packing plant his father started 25 years ago. “If he doesn’t have a decent year, he’ll be gone.”

As if the fish disease weren’t bad enough, Linson has found holes eating away at the eye sockets and backs of hard shell crabs. “It was the first time I’ve ever seen something eat the shell of a hard crab except a human being,” he said. “And we’re scared. If that’s what it does to the shell, what does it do to human skin? I ain’t going to eat anything that’s going to eat me back.”

The dead fish and rotting crabs scare many people beyond the coastal fisheries where Linson and Henries make their living. The Pamlico River basin covers a staggering 2,900 square miles — an area larger than the state of Delaware — and supports a coastal fishing industry worth $500 million a year. Its waters produce more seafood than any estuary in the continental United States except the Chesapeake Bay, and most of that food goes to market without ever being tested for poisons and disease.

Ed Noga, a fish disease specialist at the North Carolina School of Veterinary Medicine in Raleigh, has studied the growing number of fish afflicted with red sores, known as ulcerative myscosis. He calls the Pamlico “a mess. The lesions were just so massive. There were huge chunks of tissue missing. I don’t know what’s going on in that river but it’s pretty bad news.”

Taking on Texasgulf

What’s going on in the Pamlico River basin is pollution, and more of the pollution comes from one company than from any other single source — Texasgulf, operator of the biggest phosphate mine in the country. Every day Texasgulf pumps up to 67 million gallons of water out of the ground, uses it to mine ore and make fertilizer, and dumps almost all of the remaining waste directly into the river. The firm consumes as much water each day as the entire city of Charlotte, the largest city in North Carolina.

The waste from Texasgulf contains low levels of arsenic and uranium, tons of potentially toxic fluoride, and phosphorous, a nutrient that can deplete the oxygen in the river and disrupt the food chain. The company claims its pollution has little effect on the river, that the real culprits are municipal sewage, farmland runoff, and waste from other factories. Nevertheless, by its own admission, Texasgulf accounts for nearly all of the fluoride and 25 percent of the phosphorous dumped in the Pamlico. The state attributes more than 40 percent of the phosphorous to the firm.

For years, local fishers have accused Texasgulf of killing the river, but state officials and the media refused to listen. No one in power wanted to take on Texasgulf, a subsidiary of the French multinational corporation Elf Aquitaine, the sixth largest company in Europe. The firm is the fifteenth largest landowner in North Carolina, and it seldom hesitates to use its economic clout and political connections to get its way.

Take, for example, the waste water discharge permit that TG is required by law to have. Its permit expired in 1984, but state regulators have been reluctant to issue and enforce a new one because, as one official privately admitted, “there are too many jobs at risk to close that place down.” In another instance, years earlier, Texasgulf lobbyists singlehandedly quashed a bill in the state legislature that would have taxed all minerals taken from the earth — a victory that has saved the company millions of dollars.

Now, however, local residents who live and work in the poor, isolated area that surrounds Texasgulf’s giant operation are beginning to make themselves heard. Commercial fishers and environmentalists, overcoming years of mistrust, have teamed up to protect one of the most important estuaries in the country from a company the size of Dow Chemical and Coca-Cola combined — and they have started to win. The state has cited Texasgulf with 1,724 air quality violations and slapped it with a $5.7 million fine, the biggest environmental penalty in North Carolina history. And in January, Texasgulf agreed to recycle its contaminated waste water rather than dump it in the Pamlico.

Such changes have not come easily, though, and recycling is still years away. For now, Texasgulf continues to flush 3,000 pounds of phosphorous into the Pamlico every day. Pressuring the company to clean up its act has been a long, slow struggle, say local citizens — and one that is far from over.

The South of France

The roads of Beaufort County traverse corn and soybean fields. They intersect infrequently at quiet crossroads, home to small, weathered grocery stores that double as meeting places. Farm buildings and trailers, churches and shacks, and an occasional white-pillared house dot the low-lying landscape.

Here the waters, not the roads, reign. Tributaries of the three-mile-wide Pamlico flow throughout the county, gradually joining the sea in an elaborate pattern of interlocking creeks, rivers, sounds, and inlets. This estuary, sheltered from the ocean by the string of narrow barrier islands called the Outer Banks, provides the brackish mixture of fresh water and salt water necessary for the spawning of fish and shellfish. Its shallow bays and marshes serve as the nursery for much of the East Coast’s fisheries.

Texasgulf sits on the southern bank of the Pamlico near the small town of Aurora. Begun as a Texas sulfur mine in 1909, the company came to Beaufort County in 1958 when prospectors found phosphate ore under and around Aurora. They were hailed as saviors — the impoverished region’s ticket to the twentieth century. By the beginning of this decade, Texasgulf was reporting record sales of $662.5 million, most of it from the Aurora operation. The company estimated its 54,000 acres in Beaufort County contained 2.2 billion tons of phosphate reserves.

But on February 11, 1981, chairman of the board Charles Fogarty and eight TG officers and employees were killed when a company plane crashed during a storm. Within four months the company was the target of a takeover by Societe Nationale Elf Aquitaine, a French government-owned conglomerate eager to expand into the United States. When the farm crisis hit and American fertilizer companies went bankrupt, Texasgulf emerged as what Elf’s former vice chairman Gino Giusti called “the top of a lousy industry.”

Elf’s 44-story headquarters glitters in the sunlight at La Defense, an ultra-modem industrial park on the outskirts of Paris. Despite its whimsical name, there’s nothing elfin about Europe’s third-largest oil company: The firm earns $50 million in worldwide sales every week. In addition to its gas stations and petroleum products, Elf is a major producer of natural gas, chemicals, minerals, and health products. The little word is everywhere in France; Elf is as constant in French life as McDonald’s is in the states. But, until the 1981 takeover, it was virtually unknown in eastern North Carolina.

Texasgulf’s 3,000-acre plant site in Beaufort County includes belching smokestacks and huge tanks full of acid and fertilizer. Gray gypsum mountains stretch along the horizon. Twenty-five-story cranes pivot next to huge open pits. Then there are the clay slime ponds, surrounded by earthen dikes. Inside the plants, TG workers have to wear synthetic jeans on the job; the corrosive atmosphere eats holes in cotton, and in cars parked at the plant lot.

Texasgulf’s executive offices, in a building known as the White House, afford a nice view of the river. All that separates them is the spot where Lee Creek once flowed — until the company dredged it for ore, filled it with waste from other mines, and paved it to create a convenient private airstrip.

Most folks needing to get from one side of the Pamlico to the other take the free ferry. Day and night, the state ferry crisscrosses the river, carrying cars and trucks. Passengers on the 11 p.m. ferry to the south shore are invariably going to work the night shift at Texasgulf. They see the Lee Creek plant long before donning hard hats at the gate. From the ferry slip, TG glows in the distance like a strange metropolis.

In contrast to the never-sleeping industry, Aurora is almost a ghost town. A rusty, graying sign greets visitors: “We promote diversified & clean industry.” If you drive through town, make a U-tum, and go back the way you came, which takes about five minutes, the sign bids you farewell: “You are leaving a growing and prosperous town . . . y’all come back soon.”

In the early 1960s Aurora had three restaurants. Today there are none. There were seven local grocery stores, which stayed open late on Saturday evenings as people mingled up and down the streets. Now there is only one supermarket near the highway.

Main Street’s one downtown block is home to stray dogs and six abandoned stores which once housed a thrift shop, W.B. Thompson Nitrogen Fertilizer, Nellie’s Bingo Beach, the Brothers Lodge (steam-heated rooms, hunting and fishing), a school of martial arts, and Aurora Seafood. The buildings currently in use include La Ladies Shop, the Aurora Fossil Museum, the Church of God, the Church of United Methodists, a tiny library, the town hall, and Frank T. Bonner Insurance.

Apple Pie and Chevrolets

One thing hasn’t changed in Aurora in over two decades: the mayor’s last name. Grace Bonner has been mayor since 1973. Her husband Frank Bonner was mayor for eight years before that. Three years ago Texasgulf flew the couple to Paris for free. “They had extra seats on the plane. They left us in Paris and then went to Africa to some of their gold mines,” the mayor said. “We kept calling in to the Aquifane [sic] offices to find out when the plane was coming in.”

“Mayor Grace” is a tall woman partial to makeup, with coiffed brown hair. In a small town where most people wear work clothes, she sports a white silk shirt, white embroidered jacket, white pearl belt, white skirt below the knee, white high-heeled boots, diamond earrings and rings. Frank Bonner, who calls his wife the “female Mayor” and “darling,” is a little heavy and wears non-descript clothes. Their immaculate, over-decorated suburban ranch home squats resolutely on a lot with a circular driveway and landscaped shrubs.

“Texasgulf has done real well for us,” the mayor said. Her husband agreed. Before the company arrived, Frank Bonner’s insurance business only handled Aurora residents. “Now Texasgulf employees from Bath and Washington come to me for their insurance,” he said. The Bonners, who still own 349 acres, said they sold about 800 acres to Texasgulf.

“I don’t think Texasgulf’s damaged the river as much as they’re accused of,” Frank Bonner said. The commercial fishermen and environmentalists, he added, “would fight apple pie and Chevrolets. They would oppose everything. They don’t have any proof. I’m not anti-environmentalist. I’m not loving them either.”

As far as the mayor is concerned, TG isn’t doing the river any harm. “I’d like to see the river stay clean and pretty and I’m sure Texasgulf would too,” Mayor Bonner said cheerfully. “They keep us informed of everything that’s going on down there so we don’t have to read about it in the newspaper.”

Even if the mayor did have to read the local paper for news of Texasgulf, she wouldn’t find much information about TG’s poor environmental record. The Washington Daily News has been an unabashed supporter of Texasgulf since the phosphate prospectors opened their first mine more than 20 years ago, and publisher emeritus Ashley Futrell Sr.’s defense of the company has earned his paper the nickname “The Voice of Texasgulf” among many local residents.

Futrell urged landowners to sell their phosphate-rich land to Texasgulf. “It will never be mined until the people determine in their hearts and minds that phosphate is the secret to our economic greatness here in Beaufort County,” he editorialized. “If the land is not made available then the phosphate will lie sleeping there just as it has been doing for thousands of years doing no one any good.”

More recently, Futrell offered this glowing summation of the firm’s contribution to the community: “Texasgulf participates in every civic project in the county. It bailed the Salvation Army out at Christmas time and just gave 10 acres of land to the county for a landfill. Texasgulf is a tremendous economic factor in this county. If you took them out, we’d be ruined. If you took TG away from Aurora you might as well take away Aurora. They and Weyerhauser [a lumber company] own half the county, I reckon.”

Texasgulf is actually the second largest landowner in the county, right behind Weyerhauser. All told, it owns or leases mineral rights to 80,000 acres — nearly one of every six acres in the entire county. Together, Texasgulf and nine other landowners control 42 percent of the county.

The company wields pervasive influence in the community. It pays a third of all county property taxes. Its annual payroll is over $31 million. It employs 1,200 people. Yet Beaufort has a higher poverty rate than half the counties in the state. “There are no jobs locally if you don’t go into fishing,” explained Etles Henries Jr. “You can’t go into farming. Can’t go into forestry. What else is there left to do? The only thing is TG.”

Dirty Water, Dirty Tricks

At first, Texasgulfs tremendous economic power made local residents reluctant to fight the company. At least 1,600 people in Beaufort County fish or process seafood for a living. Since fishers and packers are scattered about on boats and in small plants, they have traditionally been slow to organize themselves and wary of conservationists.

But all that began to change in 1981, when a local environmental group called the Pamlico-Tar River Foundation (PTRF) successfully led resistance to a proposal by county commissioners that would have allowed Texasgulf to mine the riverbed. PTRF and commercial fishers also joined forces with a constellation of conservation groups, including the Coastal Federation and the North Carolina Wildlife Federation, to block large-scale peat mining of local wetlands (see “The Peat Wars,” SE Vol. XIV, No. 2). By 1984, when massive fish kills became a chronic problem up and down the Pamlico and dead fish covered with red sores washed up on both banks of the river, fishers and environmentalists were ready. With PTRF leading the way, citizens now began turning their attention more and more to Texasgulf.

This unusual coalition got its first real test of strength against Texasgulf in February 1986, when the company tried to downplay a massive spill. An underwater slime pipe ruptured, dumping 114,000 cubic yards of contaminated clay slime over a 26-acre area of South Creek. The company told a television reporter the spill was minor, but the evidence could not be concealed.

“We took her down there and showed her the three-foot sand bar where 13 feet of water should have been,” Henries said. “She said, ‘They lied to me again,’ and got a shot of a boy holding up a paddle with what looked like concrete on it.”

“The spill was caused by the lack of human concern,” added his father, Etles Henries Sr. “There were no inspections, no monitoring, no flow meters. You can’t use a metal pipe indefinitely. That pipe was under the creek 20 years.”

Because it was so highly visible, the spill galvanized commercial fishers and PTRF to hold a barbecue pig pickin’ to discuss what Texasgulf was doing to the Pamlico. That wasn’t an easy task. For one thing, most people have relatives who work at TG, and everyone knows everyone else in Beaufort County. “I’m classified as a rebel,” said Henries Jr., who put up the money for the pig. “People think I’m the worst thing there’s ever been.”

Several fishers who stood on the back of a pickup truck at the pig pickin’ and talked about their troubles on the river were shouted down by TG representatives. Insiders say Texasgulf paid several employees who crab part-time to defend the company at the meeting; others, they say, were frightened away from attending.

The “speak out” ended early, and the atmosphere was tense as fishers broke up into small groups to discuss what had happened. Things were tough for those who had spoken up. “A lot of people around Aurora called us liars and a lot of other nice things,” recalled Jimmy Linson. No one believed how bad things were, so Linson kept a few diseased fish in his freezer at home as proof.

Despite Texasgulf s efforts to undermine local discussions, citizens continued to serve as watchdogs. They complained to state officials, solicited help from conservation groups across North Carolina, and wrote letters to newspapers. PTRF launched an aggressive campaign to recruit new members, and within a year membership in the group leaped from 250 to 1,200.

One of those who joined was Lynda Oden, a no-nonsense tobacco farmer who lives across the river from TG near the historic town of Bath. Oden was in high school when Texasgulf arrived in Beaufort County. “We had big meetings in the school cafeteria about how great it was going to be,” she recalled. “We were all going to be nice bustling towns. Bath was supposed to grow to 10,000 in 10 years. They’re up to 200 now.”

“We were undeveloped and they snowed us,” Oden said. “The area had no idea of the implications of the plant. We ate it up. And the state didn’t look out for us.”

Oden has no economic stake in the controversy. She neither works at Texasgulf nor in the fishing industry. She does keep careful notes documenting the company’s visible impact on her community. With intelligent gray eyes and short, wavy, graying hair framing a thin face, Oden speaks her mind. “These creeks used to didn’t smell like they do now,” she said. “A lot of the trees are dead or dying. People who don’t care about TG notice the dieback of vegetation.”

Her Texasgulf file, complete with letters to politicians and scientists, has grown to fill a dresser drawer in the “old house done over” where she lives with her parents. “I hate the fact that I can’t go out and breathe the air outside my own house,” she said. When the wind blows from the south, hydrogen sulfide wafts over from the plant. “It smells like burnt oyster shells and you can see it, like a fog. It irritates the sinuses directly.”

Dead Ducks

As local citizens like Oden pressed for stricter control of TG’s pollution, the company kept breaking the law. Six months after the South Creek spill, a second major event occurred that was too blatant for the state to ignore and too obvious for Texasgulf to blame on someone else. In August 1986, agents with the state Division of Marine Fisheries were doing routine monitoring on the Pamlico three miles away from the Texasgulf plant when they were “overcome” by ammonia fumes. “They were debilitated, wheezing and coughing,” said Paul Wilms, director of the state Division of Environmental Management (DEM).

Rumor has it that someone inside the company later tipped off the state that Texasgulf had removed the plastic packing from a scrubber in a smokestack. The state requires companies to use the packing material to prevent high levels of fluoride from escaping into the atmosphere. Fluoride can kill vegetation and make human bones brittle.

“It was clearly intentional,” Wilms said. “They had clogging problems. A decision was made not to put the packing inside and not to report it.” That December, after a detailed review of TG’s records and equipment, the state fined the firm $5.7 million, citing four years of flagrant and willful violations of air quality regulations.

The heat was on, and Texasgulf was starting to sweat. It challenged the fine in court, but it also replaced seven of its top 12 plant managers. It set up a 24-hour toll-free hotline for complaints, acted concerned and friendly at public meetings, and told everyone that the company cared about the Pamlico.

To many observers, though, it looked like Texasgulf was more worried about its public image than about the river. As the public outcry increased, the company bought lots of ads heralding its employees as a new breed of “worker-conservationists.” One ad depicted mallards swimming in the plant’s slime pond. “If we didn’t care about the environment,” the ad read, “these guys would be dead ducks.”

But while TG was praising itself, the river was getting worse. The red sore epidemic peaked in June 1987, when the state trawled 40,000 dead fish off the bottom of the Pamlico. “Texasgulf tries to mislead the people that everything is fine when indeed we’re going down hill like a snowball headed for hell,” said Etles Henries Sr.

In fact, that same month, Texasgulf president Thomas Wright wrote a letter to state legislators in which he refused to take any blame for the wretched state of the Pamlico — even though a hotly debated legislative ban on household detergents containing phosphates had recently spotlighted the mineral’s devastating effect on the state’s water quality.

“Some environmental groups and writers have suggested that the Pamlico River has severe problems,” Wright wrote. “It has been implied that our Phosphate Operations on the south bank of the Pamlico River may be part of the problem.” Overstating the preliminary findings of a scientist under contract with TG, Wright continued, “Dr. Stanley of East Carolina University concludes that there have been no significant changes in water quality in the Pamlico River over the past 20 years.”

By that time, however, a new constituency had noticed the problems on the Pamlico and was demanding answers. Stories of the toxic fumes and dead fish worried tourists who vacation on the Pamlico, and the state’s metropolitan press began to take notice. Not a week went by that summer without reporters from the state’s inland Piedmont region turning up at the crabhouse run by Etles Henries Jr. “I didn’t realize the power of the press,” Henries said that August. “The people in the Piedmont, where the power is in North Carolina, are getting interested.”

Frank Tursi, a reporter for the Winston-Salem Journal, wrote 34 stories on the Pamlico in one year — and Winston- Salem is 300 miles from the coast. Tursi’s articles helped make Texasgulf a front-page story in every major daily in the state. “It was going to take an outsider,” Tursi said, “because local papers [in Beaufort County] are weak, and local politicians won’t take a hard look at TG.”

Enforcing the Law

Meanwhile, the controversy over the renewal of Texasgulf’s water discharge permit was coming to a head. Early last year, the state finally released a “draft permit” for public comment, but conservation groups questioned whether it was tough enough. Jim Kennedy, a former DEM employee turned full-time environmental scientist with the Coastal Federation, conducted a sophisticated analysis of TG’s pollution levels over a six-year period that suggested the firm had not conformed to its original permit.

But then Kennedy made an even more surprising discovery. While digging through mounds of files and documents detailing the background of the federal Clean Water Act, Kennedy unearthed a section explaining that the law requires fertilizer manufacturers to operate with zero discharge — in other words, to recycle all their waste.

This was the legal weapon opponents of Texasgulf had been looking for. Kennedy’s discovery made it clear that the waste TG was dumping was not only dangerous, it was illegal — and because the state administers federal water quality laws, it was required to do something to stop the dumping. In short, according to the law, the state didn’t have to produce scientific data to show that the pollution from Texasgulf was harming the river — the company was forbidden by law to dump its waste in the first place.

Kennedy took his discovery to state DEM director Wilms. “I just read Wilms specific sections buried in the massive regulations,” Kennedy said. “He needed to hear two or three of those paragraphs. In a case like this, it takes a Paul Wilms to mastermind a policy decision to recycle. He understands the law better than anybody else at DEM.”

Armed with the federal regulation, Wilms visited Texasgulf president Wright last December to discuss issuing a new draft permit for the firm. At the meeting, Wilms made a startling proposal: The new permit would require the company to install a closed loop system to recycle all contaminated wastes rather than dump them in the Pamlico.

More startling still, Wright soon emerged from a series of high-level meetings and agreed to set up the closed loop. “We have to improve or get in trouble, with respect to permits and public opinion,” he said at the time. “If you do nothing, the interest groups start talking about it. That leads to the confrontational thing, which has intangible costs. The company gets a reputation as the bad apple.”

Though DEM engineers say the closed loop will look like a plate of spaghetti, its result will have a certain simplicity. “The beauty of the closed system is that no discharge to the river is easy to grasp,” Wright said. “It eliminates Texasgulf from the debate of what’s impacting the water quality on the Pamlico.”

Wright admits, however, that convincing the public and TG workers that the company has changed may be tough. “The employees look at the management changes like the public does,” he said. “They think, ‘Are they just telling me that? After we’ve been discharging for all these years? You want to spend that kind of money when you’re always after me for wasting gloves?’”

“Don’t Tell Me — Show Me”

David Fritzler, an electrical instruments planner for the firm, is convinced the company has changed. He is particularly impressed with Tom Regan, the new vice president for phosphate production at Texasgulf. “Regan says, ‘Look, we’ve done things wrong. Not any more. We’re going to do them right.’”

As a result, Fritzler said, it’s now easier to fend off criticism from neighbors. “It’s hell to go down to the grocery store. People say, ‘You work at Texasgulf? You’re polluting our river.’ Regan has made us proud to work there. He is concerned with our public image. This is the first plant manager we believe in.”

Fritzler blames the state as much as Texasgulf for the environmental infractions. “We weren’t responsible about what we put in the water and the air, but the state let us,” he said. “It was like the highway patrol telling you you can go 75 miles per hour. Now we’re trying to go 55.”

Some Texasgulf workers have even harsher things to say about what the state has let the company do to the Pamlico. “It’s a shame that a big company can get away with what they get away with,” said one employee who asked not to be identified. “The state allows them through incompetence. If they’d pay me what TG pays me, I’d work for the state and burn TG’s ass. All it takes is willpower and know-how.”

Paul Wilms insists that both the state and Texasgulf have changed their approach to the environment. “Historically, their attitude toward environmental compliance was abysmal,” he said. “Today they would do things differently. They know we are not hesitant to enforce the regulations. They know the state is not going to tolerate that behavior and when we find out something they’re going to pay.”

Environmentalists and commercial fishers are a bit more skeptical, however, and some question whether the state is truly prepared to make Texasgulf obey the law. When the state issued another draft permit for the firm earlier this year, it only required the company to study the feasibility of recycling its waste. At a public hearing in May, environmentalists proposed tougher language that would require the firm to actually install a closed loop system. Texasgulf accepted the language, but state officials did not promise to include it in the permit.

Actually, if you read the company’s own promotional material, you would think Texasgulf already recycles its waste. In a glossy brochure entitled “An Environmental Commitment,” the company claims it “operates a totally closed process waste water system that has become a model for the entire phosphate industry and insures that no contaminated water is released into the Pamlico River.” A caption under a full-color photo of the plant glowing in the night reads, “Texasgulf insures that no contaminated water is released into the Pamlico.”

Whenever the recycling system is finally installed, no one says ending TG’s discharge will restore the Pamlico’s water quality. “The problems have been 50 years in the making and we would be fooling ourselves if we said it would take less than several decades to improve it,” Wilms said. “It’s better than the Chesapeake, Puget Sound, and San Francisco Bay, but now is the time to act.”

On the coast, Etles Henries Jr. is optimistic, but wary. “I think Texasgulf is getting better,” he said as his boat entered the mouth of South Creek. “They’re more cautious than they were, but the pressure has to stay up.”

As for the recycling loop, Henries hasn’t made up his mind yet. “Can I say I believe them? Not altogether,” he said with a shrug. “Anything will help, if they can keep some of their discharge out of the river. There’s no way they can stop all of the spills, but if they can cut them down then we’re in good shape,” he added, expertly docking his boat at Carolina Seafood.

“It’s to the point now where I say don’t tell me. Show me.”

Tags

Robin Epstein

Robin Epstein is a freelance writer in Louisville. (1991)