This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 2, "On the Map: New Views of the Early South." Find more from that issue here.

It has been almost five centuries since Spanish conquistadors first brought enslaved Africans to the New World, but archaeologists have only recently begun studying what life was really like for the early slaves. Investigators were slow to recognize that if they wanted to deepen their understanding of European settlements in the New World, they would have to expand their research to include the places where slaves once lived and worked. In the South, slaves played a large and critical role in shaping plantation life for more than two centuries.

Now, by carefully sifting the dirt at excavation sites across the South, archaeologists are coming up with new artifacts from the past — a comb here, a pottery fragment there, remnants of mortar, burnt bones. Slender bits of evidence, to be sure, but such small items speak volumes in the hands of specialists. With a variety of new-found objects before them, these experts are starting to build a better image of the slaves who shared life in the South with their European owners and their native American predecessors.

The findings are striking. Archaeologists have unearthed firearms, pieces of graphite for writing, trenches for walls, cooking equipment, and food remains from slave quarters. These artifacts clearly suggest that the earliest slaves used guns for hunting, built their own dwellings, occasionally learned to read and write, and prepared their own meals to suit their tastes — even though written records show that slaveholders forbade their slaves to practice these activities. In short, the wealth of buried treasure being brought to light every day reveals that Southern slaves actively sought to improve their material conditions whenever possible. In doing so, they exerted a strong and creative influence on life in the early South.

Out of Africa

The primary target of the archaeologist’s shovel has been the coastal fringes and interior flatlands of Georgia and South Carolina, where one of the heaviest concentrations of blacks in the nation once lived in relative isolation from whites. These first “low-country” or “sea-island” blacks came to the region from the West Indies when an English colony was founded in 1670.

When the planters initiated large-scale production of labor-intensive crops (rice in the 1690s and indigo in the 1740s), it required an enormous work force. Neither captured Indians from the interior nor indentured servants from Europe could meet the rising demand, and soon enslaved workers were being imported directly from West Africa by the thousands. Historian George Rogers has calculated that in the decades between 1706 and the Declaration of Independence, 93,843 Africans entered the New World through Charleston Harbor. In coastal rice-growing districts, blacks soon outnumbered whites by as many as 10 to 1.

Historian Peter Wood, in his book Black Majority, has shown that these slaves provided more than labor; they played an integral role in the settling of the frontier colony. They functioned as cultural agents, helping their European owners adapt to the new environment. Many of these Africans brought with them skilled knowledge of rice-growing, cattle-raising, woodworking, and boating. Their familiarity with rice-growing — a pursuit outside the experience of the English — literally made possible this plantation society.

African culture was thoroughly woven into the daily lives of South Carolinians. Some of the most striking evidence in support of this little-known fact is emerging from excavations at 18th-century sites such as Curriboo and Yaughan in Berkeley County, South Carolina. Digs at each plantation have revealed what may have been African-styled dwellings designed and built by slaves between 1740 and 1790. These slave quarters consisted of mud walls, presumably covered with thatched roofs made of palmetto leaves, similar to thatched-roof houses in many parts of Africa.

Although no standing walls exist, archaeologists have found wall trenches containing a mortar-like clay. Significantly, there is no evidence of other building materials at the sites. If wood had been used, for example, archaeologists would expect to find a distinctive color in the soil indicating where a post or foundation had rotted.

Since this discovery, a careful examination of written records has revealed references to slave-built, mud-wall structures. Indeed, previously unnoticed written descriptions seem to suggest that these African-styled houses may have been commonplace. W.E.B. DuBois offered a description of palmetto-leaf construction in his 1908 survey of African and African-American houses. “The dwellings of slaves were palmetto huts,” he wrote, “built by themselves of stakes and poles, with the palmetto leaf. The door, when they had any, was generally of the same materials, sometimes boards found on the beach. They had no floors, no separate apartments, except the Guinea Negroes built themselves after task on Sundays.”

African slaves also appear to have shaped material life in the colonial South by making their own pottery and preparing their own food. Clay pots known as colonoware are common finds at South Carolina plantation sites. Such low-fired earthenware, which was used to prepare and store food, often comprises 80 to 90 percent of all ceramics found at sites occupied by slaves in the 1700s. It also accounts for a significant portion — sometimes more than half — of the ceramics used in planter households. This suggests that enslaved Africans not only prepared their own meals in their cabins, but may have fixed food for planter families using their traditional culinary techniques, thus influencing local white Southern cuisine.

Until the past decade, archaeologists thought that only native Americans had produced colonoware, and it still seems likely that Indians created certain European-styled vessels such as shallow plates and bowls with ring feet which English settlers would have valued. But now most scholars agree that African slaves produced a great deal of this hand-built pottery, because much of it has been found at sites that date long after the demise of coastal Indian groups.

The first real clue that blacks made their own pottery came when some pottery fragments turned up that appeared to have been fired on the premises of Drayton Hall, a plantation located west of Charleston, South Carolina. Further research by Leland Ferguson, a historical archaeologist at the University of South Carolina, has shown that this colonoware resembles pottery still made in parts of West Africa today. Accumulating evidence thus supports the notion that colonoware is a tri-cultural product, fashioned from the collective traditions of Africans, native Americans, and Europeans.

Burning Down the House

After the Revolutionary War, however, this African-textured culture began to disappear. Homemade pots eventually gave way to mass-produced wares imported from England, and mud-wall dwellings were replaced by European-styled frame houses. As the slave trade was interrupted by war and then ended by law, the percentage of African-born immigrants in the labor force declined, as did the overall ratio of blacks to whites. Inevitably, the strong influence that African newcomers exerted on coastal life gradually came to an end.

It is easier to say with certainty that these changes took place than to say why they happened. One driving force behind the changes was the abolition of the slave trade in 1807. With the labor supply cut to a smuggled trickle, planters had an economic incentive to improve the health — and thereby the reproductive capacity — of the slaves they already owned. The changes were further fueled by the ideology developed by the proslavery reform movement, which was aimed at revising slave codes to make them more humane and “to rid slavery of its attendant evils.”

One way planters sought to improve both the physical and spiritual wellbeing of slaves was to improve housing — a change slaveowners equated with imposing European standards. The makeshift slave housing that prevailed in the colonial era soon gave way to more permanent dwellings. The mud-wall dwellings at the Yaughan and Curriboo plantations were replaced with frame houses around 1790, and the new structures were occupied until the plantations closed in 1820.

By 1830, the recommended standard for each slave family was a dwelling measuring 16 by 18 feet, raised on piers, with planked floors and a large fireplace. Although many slave quarters fell short of this stated ideal, photographs and standing ruins from the period reveal that most slaves of the 1800s lived in European-styled housing.

The standardization of slave housing gradually led to the suppression of African-influenced architecture, as proslavery reformers pushed to “elevate” the Africans to European ways. One often-cited case involved Okra, a slave from Cannon’s Point Plantation on the island of St. Simons, Georgia. When Okra built an African mud-walled hut, his owner ordered that it be burned down. The owner said that he did not want an African hut on his property. Digs at Cannon’s Point have revealed that Okra’s owner preferred a European-styled, two-family cabin.

As owners forbade slaves to build their own homes according to African traditions, colonoware pottery and other homemade possessions also began disappearing from slave quarters. England’s Industrial Revolution made inexpensive, mass-produced goods readily available, and slaves substituted imported ceramics for their own pottery. It is not known whether they made the switch by choice, because owners supplied them with cast-off European housewares, or because African traditions for shaping and firing their own pots were gradually lost.

Despite the switch from local pottery to overseas ceramics, food preparation on plantations may have continued much as it had in the 1700s. Leland Ferguson has noted that many of the mass-produced ceramics served the same function as the colonoware they replaced. For example, the most common slave-made serving vessels, small bowls, were replaced with small, mass-produced serving bowls in the 1800s.

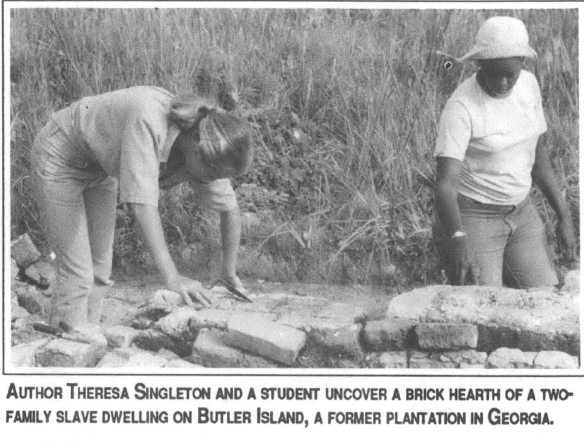

Although excavations at later plantation sites have revealed little about how blacks may have drawn on African traditions in their use of mass-produced objects, the digs do present a clearer picture of how slaves survived the rigors of day-to-day life. One of the most extensive digs took place at Butler Island, a large rice plantation off the coast of Georgia. Those of us who worked on the dig found ourselves serving as historical detectives, relying on the slimmest of clues to deduce how slaves lived.

From the Ground Up

Before we lifted a single shovel on Butler Island, we studied historical maps, deeds, plantation records, and aerial photographs to decide where to dig. Sketches drawn by an overseer of the plantation in the 1830s indicated the location of slave villages, structures used to store and process rice, and a pre- Columbian site he identified as “Indian shell.”

As archaeological sleuths, we also relied on informants. Workers at a nearby waterfowl refuge pointed out areas where they had unearthed artifacts, and former tenant farmers recalled places where they had seen ruins of the plantation.

Once everything above ground was carefully mapped and recorded, we began to dig. Each site was measured into squares forming a grid, and the exact position of every significant find was reproduced on paper.

Most of the structures we located were slave cabins. Slaves on Butler Island lived in dwellings measuring roughly 24 by 28 feet, made from cypress planks, with fireplaces that measured eight feet across. The fires in the fireplaces burned very hot at times, a fact attested to by the buckling and separation of the hearths from the outer chimney walls and by findings of food bone burnt to a whitish-blue color.

When we located building hardware such as hinges, locks, and shutter pintles, we were able to work out the placement of doors and windows. And when we found no windowpane fragments, we deduced that the windows were not glassed.

Outside the cabins, we used clues uncovered just below the top layer of soil to spot areas where slaves washed clothes, tilled gardens, burned trash, and penned pigs and chickens.

Inside the cabin outlines, stoneware fragments indicated that the typical slave household possessed only two or three stoneware crocks used to store molasses, cornmeal, and salted meats — foods frequently rationed to slaves by planters. Bottle fragments, clay pipes, and medicine vials documented that slaves sometimes received rations of tobacco, pipes, patent medicines, and alcohol.

Hunting and fishing gear, cooking equipment, and the remains of plants and animals all provided evidence of what slaves ate. Food bones indicated that beef and pork contributed most of the animal protein to their diet, but slaves supplemented these rations by hunting and fishing — adding ducks, fish, raccoon, opossum, turtles, and shellfish to the menu.

Who Studies the Past?

Such findings are significant. Because slaves recorded almost nothing about how they lived — and because so many aspects of their daily lives were dictated by European owners — the study of African-styled dwellings and pottery can give us a better understanding of how Southern slaves viewed their own lives.

It appears, for example, that the use of colonoware to prepare and serve food enabled slaves to maintain their old culinary practices and social customs or establish new ones. In addition, blacks continued to exercise their creativity in building design and the use of space whenever possible. Unusually small, 10-foot-square cabins suggest the recurrent use of an African floor plan. In this subtle way an African perception of space may have been perpetuated until fairly recent times.

Such observations demonstrate how rapidly slave archaeology has grown from modest beginnings into a specialized interest. Early studies offered little more than an embellishment of written sources, but recent excavations provide physical proof of the existence of slave-made pottery and African-styled buildings, as well as the household equipment, personal possessions, and family diets of early generations of black Southerners.

Yet despite such findings, most of the archaeological treasures being unearthed have been stockpiled away from public view. Specialists share their research with one another, but rarely with ordinary citizens. And black participation in this specialty remains scant. Of several hundred professional archaeologists in the country, fewer than 10 are black, and only four of these have been involved in investigating plantation sites. It is interesting to speculate about what might happen if more young black students were to equip themselves to search for their own past by studying the objects their ancestors left behind. Such participation is crucial for the study not only of African-American life, but of Southern society as a whole.

Tags

Theresa A. Singleton

Dr. Theresa A. Singleton is an archaeologist with the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. She is the editor of The Archaeology of Slavery and Plantation Life, Academic Press, 1985. (1988)