This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 1, "Unsettling Images: The Future of American Agriculture." Find more from that issue here.

My grandmother was the keeper of the farming traditions. She ran the family farm, actually a collection of small farms accumulated by her father, who, I’m told, gave her a shotgun one Christmas when he gave dolls to his two other daughters. Evidently he had high hopes for my grandmother. But blessed with just one daughter — not the shotgun totin’ or farming type — my grandmother was left with me, her only grandson, to concentrate on as she neared eighty. “Don’t you think you might want to be a farmer?” she asked over and over — probably because I never gave the correct answer.

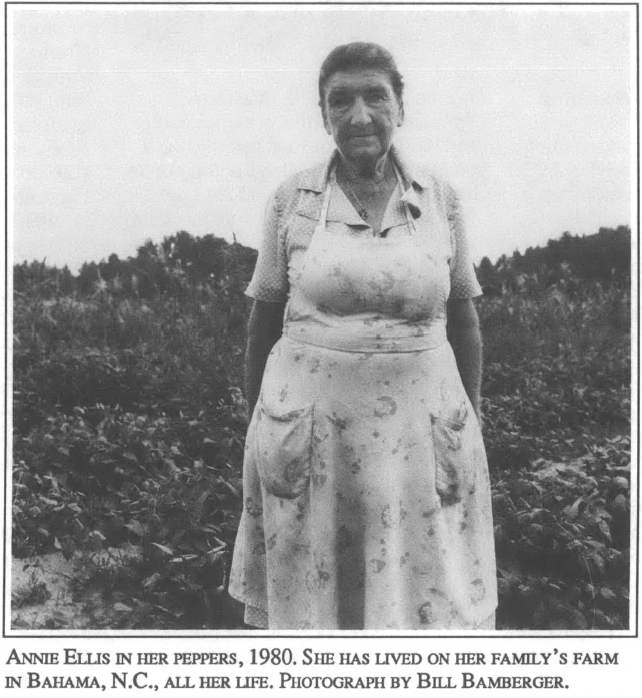

She persisted. In her ’57 Ford we spent many an hour driving along dusty back roads surveying fields and crops. Each field was a little different and she gave a running commentary on the nature and quality of the soil in each, sometimes slowing down or stopping to point out differences within a single field. She’d tell me that this field would produce good corn, but the one across the road was slightly better. She’d rarely tell me exactly why. Some things are learned more intimately if you don’t approach them too intellectually. To this day, I think I know something about the soils of Madison County, Tennessee. My grandmother taught me about them.

But my grandmother’s efforts were in vain. I was not to be a farmer. Still, in her efforts can be seen the optimism that guides all farmers. In what must be humanity’s ultimate act of faith and optimism, farmers sow their seeds every spring not knowing if the rains will come or if pests or disease will strike down their crops. The farm is no place for a pessimist.

The family farm produces not just crops, but farmers. As if by instinct, as a cow nudges its newborn calf to the nipple, the farmer seeks to pass his or her life on to the next generation. Yet it was not to be with me. And increasingly it is not to be with a whole generation of young people coming up on the farm. Educated to be farmers, these children are inheriting the accumulated wisdom, the rich legacy of experiences their family and community have had in farming for generations. But they will not become farmers.

Most of today’s farmers would still become farmers if they had it to do over again. But in a recent survey by North Carolina State University, a majority said their own future in farming was doubtful. And a resounding two-thirds responded that they did not see farming as a “real option” for the next generation.

Today’s farmer is a producer of raw materials and a consumer of manufactured goods. It is a position not unlike that of Third World countries and their peasantry. In the modem supermarket there is an aisle for fruits and vegetables and an aisle for meats. And there are a dozen or more aisles for processed goods. Here you can find dollar loaves of bread with four cents worth of wheat, and potatoes for $2 a pound in the form of potato chips.

The money to be made in food is not made in growing it — growing food is just one procedure on the long assembly line, the grower of the food is just one more worker in the American food factory. The money is in the processing, packaging, retailing, and advertising of food. The transformation of the neighborhood Mom and Pop grocery store into national supermarket chains has given the processors and retailers enormous power over the individual, unorganized farmer. The “local” supermarket doesn’t want to deal with the local farmer and a pick-up full of tomatoes.

The tomatoes stocked on the shelf are not there because they won a taste contest. Nor are they cheaper. No, they’ve arrived in town because the local manager knows it is easier to order all fruits and vegetables from a single source that can supply them year-round than to deal with the area’s farmers. So most farmers learn to specialize by growing only a couple of crops and marketing them to middlemen. As early as the 1950s this trend was evident even in the kitchens of farm families — not since the fifties have farm families grown as much as half of the food they themselves consume.

As consumers, farmers have the biggest impact on the multibillion dollar farm supply business. But in recent years interest on farm debt has become almost as big an expense as that for machinery, fertilizer, and pesticides. Since 1977, prices received by farmers have increased 28 percent. But prices paid out by farmers have risen 63 percent. While the assets of farmers have tumbled, debt has risen. To our concern about Third World debt might be added the growing problem of farm debt — $205 billion in 1985.

Today’s family farmer is on the way to becoming a sharecropper. The farmer may own the land, but the farmer does not control the land. The boss-man has become a big corporation. The farmer, like the sharecropper of the ’30s, produces crops for the boss-man, and buys from the boss-man at the boss-man’s prices. And like the sharecropper of old, today’s farmer has lots of debts, little power, and few alternatives.

The family farm struggles to survive by doing what it does best — producing food most efficiently. That’s right. Every USDA study I know of over the past 25 years has shown that the family farm is the most efficient size unit in American agriculture. Texas Agriculture Commissioner Jim Hightower put his finger on the problem of large-scale farming years ago when he asked, “Who will sit up with the corporate sow?”

Efficient farming is not 9-to-5 farming. Efficient farming starts with the lessons parents and grandparents give to the young ones. They are lessons about how to read the soils, how to treat the livestock, how to repair the tractor and how to be a good neighbor. By shaking our faith in the future, the new sharecropping system emerging in this country attacks the agriculture that is educating the next generation of farmers. What will happen to future generations who try to farm without the knowledge and wisdom of today’s farmers? How will we learn that farms are not factories and in any case that farmers cannot be trained to be farmers as factory workers might be trained on the assembly line? What kind of crisis will it take?

The farmer expecting to be run out of business, and the farmer who cannot in good conscience promise the kids a future in agriculture, becomes a poor and ultimately dangerous farmer — one who tries to “get by” without planting cover crops, repairing the fences, worming the animals. Too often the work of the farmer is determined not by the needs of the land or community, but by the dictates of politics and the requirements of High Finance for whom the farmer sharecrops. It is, in fact, becoming increasingly difficult to be a “good” farmer.

When I drive past the mobile homes and sagging barns so commonplace in my native South, I wonder if we plan on staying here very long. It doesn’t look like it. I don’t get the feeling we are treating agriculture as though it must be permanent, as though we must “do right” by it today in order to have it tomorrow. Perhaps a little “manifest destiny” lingers in our blood telling us that once again we can do horrible things to the land and people without paying a price.

Before she died, my grandmother pointed to her land and told my mother and me that we’d live to see the day it was worth $1,000 an acre. We thought she was crazy. Now a big highway runs along the edge, and there are factories, car dealerships, subdivisions. The land is probably worth $5,000 an acre today — that is, if you are willing to see it paved.

Unfortunately, we have no mechanisms for setting the true long-term value of such land and certainly no way of placing a value on the worth of the family that farms that land — on what they really contribute to the well-being of the community. In our economy, that which is priceless becomes valueless. Today’s price tag becomes the chief planning instrument of the future. Literally, we get what we pay for. My grandmother understood that the value of the land was greater than the price. If agriculture is ever again to prosper, it will take more farmers like her. Just as important, it will require non-farmers adopting some of her attitudes to strengthen the all-important relationship between farmer and society. Until then, agriculture will suffer.

Evidence of agriculture’s decline can now be found in eroded fields, falling barns and foreclosure sales. But in a sense, these are the effects of the loss of optimism, the loss of control over the future, the loss of the “culture” in agriculture. It is the result of agriculture becoming agribusiness. Knowing that the children will graduate from high school and leave the farm permanently, the farmer makes rational, businesslike decisions. Things slide. Farmers know they can take care of society, but many no longer believe society will care for them — or their descendants. In the past decade we have lost hundreds of thousands of farms — farms gobbled up, paved over or just plain abandoned. Can the nation afford such a loss without injury to its future? Perhaps it is our descendants who should worry.

Farming has always been a uniquely cultural activity, highly influenced by the farmer’s sense of time and place. And, as always, its wise practice depends on the existence of strong ties with the past, with our ancestors, and a solid bond with the future — our children. It rests on the strength of relationships, complex relationships which are revealed in the Manifest Destiny exhibition. In the photographs presented here, we see that farming is not so simple as sowing and reaping. And in the policy statements from the Rural Advancement Fund that follow below, we see that practical solutions that address fundamental flaws in these delicate, complex relationships are within our grasp.

Tags

Cary Fowler

Program Director, Rural Advancement Fund (1988)