A Portrait of American Agriculture — A Look into the Future

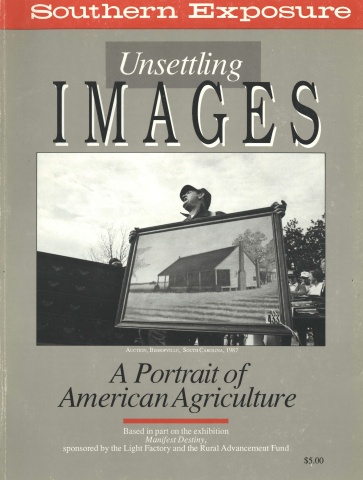

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 1, "Unsettling Images: The Future of American Agriculture." Find more from that issue here.

This edition of Southern Exposure draws heavily on the farm advocacy work of the Rural Advancement Fund, especially a photographic exhibition called “Manifest Destiny” and a citizens forum on agricultural issues held in honor of the organization’s 50th anniversary. Like the settling of America through the doctrine of manifest destiny, the unsettling of the family farm is neither accident nor act of God. It is the result of purposeful policies that favor food wholesalers, cotton brokers, grain merchants, and financial middlemen over the individual producer.

Farmers of late have won significant credit relief measures that, if implemented, could ease their immediate financial burdens. But the Farm Crisis, as discovered and now lost by the mainstream media, is far from over. Even the Economic Research Section (ERS) of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, a fountain of cheery news for high-tech farming, admitted in late 1987 that “approximately 100,000 commercial-size farms [those with sales of $40,000 or more] could face potential losses of an estimated $6.3 billion” in the next year.

For the South, the forecast is particularly grim. “The Southern Plains, Delta, and Southeast are the only regions where the problem of potential loan defaults is getting worse,” writes ERS economist Gregory Hanson. “The average size of loan loss per Southern farm stands to be the highest in the nation.”

As members of the United Farmers Organization attest herein, regional distinctions pale compared to the larger problem. The crisis is national in scope and goes far beyond the need for debt restructuring; it goes to the heart of our images and attitudes about the people who till the earth and put food on our tables.

From plantation master Thomas Jefferson to hobby rancher Ronald Reagan, the yeoman farmer has been at once romanticized and vilified. They are praised for their independence, their work ethic, their democratic instincts. Yet for more than a century, government policy has considered them expendable, like so many stick figures and country hicks — too dumb to know what’s good for them, better unseen and removed from the centers of power and commerce.

Expendable farmers are the byproduct of a policy preoccupied with increasing productivity rather than sound land use, quality food, humane labor practices, and parity — the concept that farmers should receive enough to cover their production costs. Ponder the fate of Edna Harris (page 4). Even though she paid off her farm debts and netted just enough to support her family, a federal agent denied her request for a new production loan because her income-to-assets ratio didn’t meet his image of “a well-managed farm.” When she planted corn seed donated by Midwestern farmers, the state college experts warned it would fail because the seed didn’t conform to their pretreated standard.

Most of us are afflicted with our own distorted notions of agriculture. As long as our supermarket’s shelves are well stocked, the troubles of the average farmer seem a distant tragedy. We ignore the fact that federal farm programs push farmers to get bigger or get out so larger profits can go to food processors like Ralston-Purina, RJR Nabisco, and Tyson Foods. Small farm advocates like the Rural Advancement Fund have protested this injustice for decades. We should have listened. Even the New Deal wound up promoting automated agriculture while abandoning hundreds of thousands of small landowners, tenant farmers, and sharecroppers. The cotton South withered and California agribusiness took root during the last farm depression. The outcome this time around could be worse.

Back then, the Southern Tenant Farmers Union organized the displaced and created a national fundraising campaign to dramatize their struggle. The annual National Sharecroppers Week, begun in 1937, soon attracted prominent supporters like Upton Sinclair, A. Philip Randolph, and Eleanor Roosevelt. In 1943 it became the National Sharecroppers Fund, which in turn set up the Rural Advancement Fund to operate tax-exempt programs. Over the years, NSF/RAF took up the cause of Louisiana sugarcane cutters, Mexican immigrants (which led to Cesar Chavez’s UFW), Tennessee sharecroppers evicted for registering to vote, migrant children, and small farmers experimenting with organic farming.

In recent years, RAF (as the organization is now generally known) has launched a minority voter education program and a project to monitor the criminal justice system in rural counties, but its chief focus remains agriculture. It combines a grassroots organizing effort to save small farmers with an international research and advocacy program to preserve seed diversity and block the complete corporate takeover of world agriculture through biotechnology and genetic engineering.

It’s time the rest of us realized that french fries come from potato farmers, not McDonald’s, before it’s too late. Family farmers don’t want our nostalgic sympathy; they want us to evaluate the consequences of their demise and become selfish advocates for a better future.