This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 1, "Unsettling Images: The Future of American Agriculture." Find more from that issue here.

It had been two weeks since the president of the Farm Bureau had gone on the Today show and told Jane Pauley that the farm crisis was over, but it was still the topic of much conversation down at the Lowry Livestock Feed Mill in Harmony, North Carolina. Farmers gathered around the big black heater in the comer, next to shelves lined with boxes of cattle dusting powder and swine wormer and udder wash, and talked about what an outrage it was.

“Did you hear him?” said George McAuley, a local dairy farmer. “He said the farm crisis is over, that the farm has turned the comer.”

Arnold Suther, another dairy farmer, let out a laugh. “Guess he hasn’t seen milk prices lately.”

“He’s in the hip pocket of Reagan,” McAuley said.

“They’re all in the hip pocket of Reagan,” Suther said. Then he looked concerned. “Don’t get us wrong,” he added. “We’re not anti-Farm Bureau. We just want the Farm Bureau to stand up on its hind legs and scream about how bad things are for the farmer. If the Farm Bureau wants a bill passed, it’ll pass.”

“So what?” Vic Crosby retired from farming a few years ago, but he still comes into the feed mill to talk with his neighbors. “They can take a bill that’s been passed into law and put it through the bureaucracy and completely nullify it. You want something done, you got to do more than pass a law.”

The farmers gathered at the feed mill know from painful experience that the farm crisis is far from over. One by one their friends and neighbors have lost their homes and their land. Nearly one out of every four farms in the state has disappeared since 1980, forced out of business in a national upheaval that has wiped out an estimated 600,000 farms and 70 million acres of farmland nationwide. Most were modest, family farms saddled with enormous debts and struggling to survive in a market dominated by huge corporate farms and food processors. In all, federal figures show, more than one million people have been driven off their farms in the past seven years. Today, for the first time this century, fewer than five million Americans live on farms.

Contrary to what the Farm Bureau might say, things are not getting much better. In fact, government studies show that the potential for farmers defaulting on their loans is actually increasing in the South, and that farmers nationwide are likely to default on $10 billion of loans in the next two years alone. Of the estimated 640,000 family farmers who remain, 120,000 will be forced to shut down within two years, and another 200,000 are on the verge of collapse.

George MeAuley and Arnold Suther and Vic Crosby and the other farmers at the feed mill know all this — and they are among the growing number of farmers who are organizing to put a stop to it. Across the country, farm groups have sprung up from the grassroots, groups like Groundswell in Minnesota, Iowa Farm Unity, the Dakota Resources Council, and the Kentucky Community Farmers Alliance.

Over the past few years, Southern farmers have been especially active building a low-key, grassroots campaign to save family farms threatened with extinction. It has been a quiet fight: There have been no boycotts, no armed confrontation, no talk of forming an independent political party. Instead, there have been lots of late-night meetings and small-town organizing and slow, steady pressure on Congress.

McAuley, Suther, and Crosby all belong to the United Farmers Organization (UFO), a group formed four years ago by farmers in North and South Carolina determined to put a stop to farm foreclosures. News of the new organization spread quickly across the Southeast, and before long 1,500 farm families in 83 counties throughout the Carolinas had joined the UFO.

“One farmer by himself probably thinks he’s the only one having trouble,” Crosby said. “You don’t share your troubles unless your back’s up against the wall. Each farmer himself can’t afford to go to Washington for a week to try to lobby, but a thousand of us can send one person up to do the job for us.”

McAuley nodded. “They’ll listen to three or four better than they’ll listen to one. And you get a politician in a crowd of 20 angry farmers, he’ll at least talk nice until he gets out of that crowd. Numbers are the only thing they listen to.”

“Politicians understand numbers,” Suther agreed. “One person doesn’t mean nothin’ to them.”

The Nickel Auction

Farm activism in the South dates back well over a century to the early 1870s, when the Grange established itself as the first national farm organization. With more than a million members, the Grange dedicated itself to fighting the bank and railroad monopolies that had dominated farm life.

By 1887, however, the Grange had been virtually overshadowed by the Farmers Alliance, a young organization that began in the South and sparked a popular movement across the Midwest and Great Lakes. The Alliance grew rapidly into a full-fledged agrarian revolt that drew millions of farmers into a struggle over who would control the land, banks, and railways that shaped almost every aspect of everyday life.

The group formed rural coalitions that cooperated to buy and sell farm goods, and contended that banks were run by the rich as a sort of private government controlling the national currency for the benefit of a wealthy few. Alliance members from Texas and Nebraska, from North Dakota and Georgia flocked to form the Populist Party in 1892, but by the turn of the century high freight costs and low prices for their goods had forced many farmers off their land and into the cities and factories to look for work. Many farmers who remained were forced into sharecropping, a second-class status that kept them in constant debt and perpetual poverty.

The defeat of the Populist movement set the tone for farm activism in this century. Farmers found themselves increasingly isolated from consumers, and their dwindling numbers made it difficult to organize effectively. Still, farmers continued to fight back. During the Great Depression members of the Farmers Holiday Association took to the streets to demand parity — laws guaranteeing farmers prices equal to their cost of production. Farmers blocked roads to markets and dumped food on the pavement to protest unfair prices. They halted farm foreclosures by disarming deputies, and in Iowa they stormed a courthouse and nearly lynched a judge who refused to put a moratorium on foreclosures. Afterwards the state declared martial law, and foreclosures were conducted at bayonet point.

Vic Crosby grew up in Iowa during the Depression, and he remembers going to a “nickel auction” where farmers put up a hangman’s noose and dared anyone to bid over a nickel for their neighbor’s farm. “No one bid more than a nickel, and the man got to keep his farm,” Crosby recalled. “There’s been a little of that kind of action this time around, but not so much as there was back then.”

Although the UFO hasn’t relied on the confrontations of the past, it owes much to the structure of earlier farm organizations. Like its predecessors, the UFO is a grassroots group built on a network of county chapters. It is also one of the few interracial farm groups in the South since the Populist movement with both blacks and women holding prominent leadership roles.

If the UFO has inherited the organizing legacy of earlier farm activists, it is also heir to many of their economic and political goals. Today, many of the issues are the same as those raised by the Farmers Alliance 100 years ago. The UFO has called for a halt to farm foreclosures, a fair price to cover the cost of production, and sweeping credit relief for farmers forced to borrow heavily to survive.

At the federal level, the UFO has already won legislation that protects family farmers who are deeply in debt and that permits borrowers to serve on local loan appeals committees. Now, the group is fighting for new laws that would replace federal farm subsidies with fair market prices and require borrowers and lenders to try and resolve their loan disputes through state mediation.

The UFO actually got its start with a telephone hotline organized by the Rural Advancement Fund (RAF), a farm advocacy group that grew out of the Great Depression. RAF began the hotline to give information and immediate relief to farmers struggling to survive. One of the first farmers to call was Edna Harris.

Lender of Last Resort

There is little about Edna Harris to suggest the stereotype of a hardened political activist. A great-grandmother at 61, she has lived on a North Carolina farm in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains since her father moved the family from West Virginia nearly 50 years ago. When he left to build barracks at Ft. Bragg shortly before World War II, Edna was 13 years old. She raised her brother and two sisters on her own until she finished school.

Edna eventually married and began sharecropping tobacco with her husband Lonnie. A federal loan enabled them to buy a small plot of land in 1964. The loans kept coming, and like other small farmers, Edna and Lonnie heeded the national push to grow, grow, grow. They built a hog parlor and bought more land and planted from fence row to fence row. And, like other small farmers, Edna and Lonnie nearly lost everything when overseas markets dried up and prices began falling in the late 1970s. To make matters worse, Lonnie had a heart attack in 1979 and has been disabled ever since, leaving Edna to run the farm.

From 1981 to 1984 Harris borrowed $106,000 from the Farmer’s Home Administration (FmHA) — the federal lender of last resort for farmers — just to pay the costs of operating the farm. “We paid every penny back, and we were not delinquent with any payments ever,” she says. After paying off the loans each year, “maybe you’d have $8,000 or $9,000 left for the family to live on.”

Then, in 1984, a FmHA official visited the farm and told Harris he was turning down their application for another loan. Even though she owed no money, he called her a “poor manager.”

“That was a blow below the belt,” Harris said. “That’s the term FmHA supervisors pin on everybody they want shut down. He knew that if we couldn’t get operating money for the next year we wouldn’t be able to live. He told us to sell some of our land, and we did, but it wasn’t enough.”

That was when Harris saw a magazine article about the RAF hotline. “It said don’t panic — call. So I did. It was a North Carolina number. If it hadn’t of been, I couldn’t have called.”

RAF helped Harris appeal her loan application all the way to the FmHA in Washington, and she began to talk to her neighbors about joining the newly-organized UFO. In 1985, 65 farmers attended a meeting in Iredell County, and nine joined the organization that night. The FmHA began to threaten farmers who joined, and one official told Edna’s neighbors that he would help them get loan money to buy her farm.

Then came the drought of 1986 — a disaster that proved to be a turning point for the new organization. There was no rain, none. Little farms were wiped out, and even big combines began to close. “The UFO said we should start at the grassroots” — Harris says the word the way she says soil or earth, as if it were a part of nature — “and where would the grassroots be but in the county? So we went to the county commissioners and got them to pass a moratorium on farm foreclosures.”

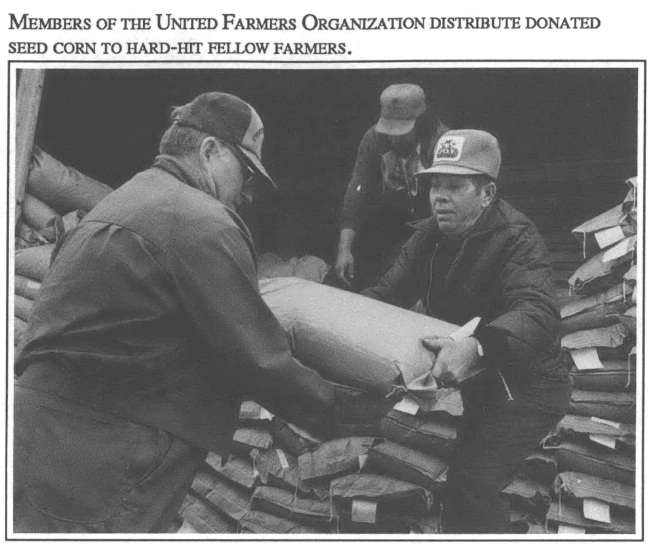

When Midwest farmers came to the aid of their Southern counterparts, Harris helped direct a haylift that distributed 30,000 bales of hay and $23,000 to farmers in her area. “We kindly united and helped one another,” she recalled. “We got hay and seed corn and gave it to those who needed it. If it hadn’t been for that corn, there would be a lot of us that would’ve been completely wiped out in 1987.”

The haylift drew more farmers into the UFO and proved that they could unite with other farmers to fend for themselves. “We didn’t just work with ourselves,” Harris said. “We kept on working our way right on up the ladder to Washington, D.C. We organized. We organized in committees, and we set out to get legislation that would help the family farmers.”

“One Common Bond”

Early in the mornings, before dawn, Harris would sit in the milk barn with a stubby pencil and scribble her thoughts on the backs of yellow Carnation Company Bulk Milk Pick-Up Records. The words came quickly. “We are all bound together with one common bond — survival,” she wrote. Or: “The farmer doesn’t want more credit, but equity for what we have to offer.” Or later: “Can we survive? Only if we unite and let the lawmakers hear our voices.”

“I just sat out there in the milk barn and wrote them things down,” she recalled, sitting at the dining room table where she answers the local UFO hotline until well past midnight every night. “I never had any idea I’d get up and say them.”

But she did get up and say them, at meeting after meeting, in county after county. She kept using the words “unite” and “survival” to anyone who would listen.

“Farming has been the backbone of this nation,” she said once, “and if you break a farmer’s back, you break the backbone of this nation, and it’s broken forever. When they do away with the family farmers, they’re going to find out that the American way of life has been crippled.”

Harris did whatever it took to get farmers to meetings. “Once I told a bunch of men, ‘Please don’t let me be the only farmer down there with all those politicians, and me a woman at that.’ And when the meeting started, sure enough there were 65 farmers there. They stuck together.”

Her granddaughter Jeannie chortled loudly at the memory. “And besides that, it would have made all those men look bad, you down there all by yourself,” she laughed.

As times grew tougher, so did the meetings. “I remember a man stood up at a meeting and told about how he had been going to kill himself, and the tears were just streaming down his face,” Harris said. “He said he’d rather be dead than to tell his wife and children that he was a failure, to tell his mother she was going to have to leave the farm where she was born and find another place to live. When you hear something like that, you can’t help but be changed.”

When asked why the UFO doesn’t follow in the footsteps of farm activists of the past, why farmers today don’t disarm deputies or put barricades on the roads to the market, Harris just shook her head. “Really, there’s no point for that If you have mandatory mediation, if you can get your lenders to listen and give you more time — that’s all we’re asking for. We’re not asking for blood. We’re not asking for war, for rebellion. We’re just asking for a fair chance.”

But later, driving through the rolling farmland and pointing to the fields where some of the best young farmers in the county have been driven out of business, Harris grew frustrated. She never raised her voice, but her faith was visibly shaken by the sight of so much land lying idle.

“You just don’t know how angry it does make us, and you don’t know how we feel when we find out our farm may be put on the block and sold. Now I have never been a vindictive person. I raised my boys, and I always told them, ‘You can be boys, but you don’t have to be mean. You can be decent and respect other humans.’ But when I heard we were going to be put on the block, I told my son Jim, I said, ‘Son, if it comes to that, if they put a notice in the paper and auction off our land, I’m gonna go to your house and get that gun of yours — I don’t even know what kind of gun it is — but I’m gonna get that big pistol of yours and I’ll swear I’ll go over to the Farmer’s Home office and let that man have it right in the face.’”

She stopped suddenly, and turned to look out the window. “That’s how desperate I was. And I regret I ever said it, because you know, my boy went out and bought a lock and put it on that gun. He said, ‘Momma, you scared me, and I’m not gonna let you do it. It’s not worth it. You taught me that hurting people was wrong, and now I’m gonna teach you something.’”

“A Hurtful Thing”

Edna Harris is not the only woman who has taken a leadership role in the UFO. Indeed, one of the most striking things about the group is its emphasis on encouraging men and women, black farmers and white farmers to work side by side to change the way America does business.

Another woman who was instrumental in the early days of the UFO was Annie Mae Chavis, a black farmer in Cumberland County, North Carolina. Like Harris, she runs her own farm and organizes for the UFO. “It gets tough,” she said, sitting in the small home she and her husband built 25 years ago. “I have to figure out my papers. I have to get my fertilizer. I have to drive a tractor from Monday morning to Saturday night. I have to run my house. And I have to do everything I do with the RAF and the UFO. It’s hard, but I do it because I’m sick and tired of farmers losing what they all worked the better part of their days for. That’s a hurtful thing. A hurtful thing.”

Black farmers like Chavis have been especially hard hit by the farm crisis of the 1980s. Black-owned farms are generally a fourth the size of the national average, and 79 percent sell less than $10,000 of agricultural products a year. What’s more, black farmers have always had a tougher time than whites getting federal loans, making it hard to get through a bad season. As a result, blacks have been losing land at a rate two and a half times that of whites. At their peak in 1920, black farm owners numbered almost a million. By 1982,only 33,000 remained.

Steps to the Farm Crisis

1. From the late 1960s to late 1970s, the future seems bright for U.S. farmers. When the value of the dollar falls in 1971, U.S. grain becomes a good buy abroad. In the next decade, farm exports jump from $7.9 billion to $43.7 billion.

2. Expansion becomes the buzzword of the decade. The U.S. government pushes farmers to plant “fence row to fence row” and encourages them to use the soaring value of their land to borrow heavily to buy more land and equipment.

3. In 1977, warning signals begin to appear. The bottom starts to fall out of overseas markets. Many countries become debtor nations and begin producing their own food to cut costs. Interest rates and inflation in the U.S. soar.

4. From 1981 to 1982, bumper crops overflow silos after the U.S. bans grain sales to the U.S.S.R. Farmers take on more debt to stay in business, but prices for farm goods fall below the cost of production.

5. From 1984 to 1986, high loan costs and falling prices for food and land combine with a series of devastating droughts to wipe out many farmers. Banks seize the land of those who can’t repay their loans. In 1985 alone, an estimated 400,000 are forced to give up farming. As family farms close, profits continue to rise for lenders, large corporate farms, and giant food processors.

“I’m just thankful I can borrow money and keep farming,” Chavis said. “I’ve always had a harder time than whites when I went to borrow money. I’d be sitting there at the FmHA desk with all my papers, and a white farmer would just walk in and walk out with the money he needed. But when you boil it down to now, this present day, I’m glad I couldn’t borrow the money they could borrow. If I had borrowed as much as they borrowed, I wouldn’t have my farm.”

Chavis began organizing for the UFO in 1984, going from farm to farm, sometimes from sunup to sundown to tell farmers about the organization. She found organizing to be harder than she had expected.

“If I had a meeting in my own home in my own neighborhood right now, I’d be lucky if three people came,” she said. “It’s the hardest thing to get people organized to try to do some good or help the community. I might go and talk to 100 people, and if five would be at the meeting, I’d be smiling. You might get a little bit more if you promise to feed ’em free. That’s off the record, now.”

After years of work, however, her efforts finally paid off. Two nights earlier, 23 farmers had come to a meeting and formed the first UFO chapter in the county. One man donated $100 so the group could open a bank account and pay for a meeting place every month.

“If it hadn’t been for the UFO and the RAF, a lot of people would have lost everything they had, but people still seem reluctant to join sometimes,” Chavis said. “You know, I never seen so many doors close — stores, banks, land laying idle, buildings falling down, factories closing down, tractors standing still. That might have something to do with it. People are losing faith in government. They don’t want to get involved, because they don’t think it will make no difference.”

The group has made a difference, though — especially when it comes to uniting white and black farmers. Someday, Chavis said, the UFO might grow strong enough to build on the efforts of the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

“It perhaps will be thataway if it lasts long enough,” she said. “Because we honestly sticks together good. We feels for one another. But the blacks can’t make it by themselves, and the whites can’t make it by themselves. So we got to unite, and we got to stick together if we want to get anywhere. I don’t like an organization that’s all black, and I don’t like an organization that’s all white. Because then we never get together and learn from one another. Being by yourself, you’ll never get nowhere.”

For herself, Chavis wants only to farm tobacco long enough to retire. “I hope one day we can live happy, even if I don’t have to farm no more. I hope one day we can just quit farming and live in peace. I sacrifice a whole lot today so that maybe tomorrow we’ll be out of debt. If tomorrow ever comes.”

For the UFO, Chavis wants an organization strong enough to allow all farmers to live in peace. “The UFO opened doors and cracks where we can stick our head in and fix to walk in. Pretty soon we won’t have to peep in the door — we’ll walk through the door,” she said. “As you organize you get stronger and stronger. The politicians listen more to 500 people than they would one. So I consider that a good thing, not just for the farmer, but for everyone concerned. I knows we have some power in Washington, D.C. now, and that’s a good thing.”

Credit and Price

The power that farmers like Harris and Chavis have helped organize paid off on January 6, when the Agricultural Credit Act became law. The UFO lobbied hard to make sure the law included sweeping new rights for farmers, and every member of the North and South Carolina congressional delegations voted for the bill.

“This is the first significant credit relief farmers have ever had,” said Benny Bunting, a North Carolina hog farmer who chairs the UFO legislative committee. “The law contains a mouthful of new borrower’s rights we’ve never had before.”

Among the new rights for farmers contained in the measure are provisions that:

— force federal agencies to restructure a farmer’s debt if the new loans would bring more money than selling the farm.

— guarantee farmers access to federal appraisals of their land.

— provide farmers the first option to buy or lease their land if it is being sold by federal agencies.

— establish a loan appeals process independent of the FmHA and give borrowers the right to sit on the appeals board.

Although Bunting worked hard to make sure the new law protects the rights of family farmers, he said “our main job now is to watchdog it to make sure the regulations they come up with will enforce the new law.”

He also said the UFO will now turn its attention to the issue that has eluded farmers for 100 years: fair prices for what they produce. “We basically have the credit side of the problem passed now, and it’s a big win. But if we don’t take care of the prices to go along with that, it’s going to be a short-term fix.”

When family farmers in the UFO talk about prices, they are talking about nothing short of completely revamping the way the economy works. Despite spiraling food prices, most family farmers actually pay more to grow their crops than they get at the market. Their own cost of production has risen — seed, feed, fertilizer, tractors, gas and oil — but today the prices they receive for their products are only half what they were in 1981 when adjusted for inflation. What they want is what peanut and tobacco growers already have — a system of supply management that allows the Secretary of Agriculture to allot quotas for farm products based on the domestic and export needs. By controlling how much is produced, the government can ensure that prices remain above the cost of production.

“Right now, grain is subsidized by the government,” Bunting noted. “Farmers sell their grain in the marketplace, and the government makes up the difference. We want to get our money from the marketplace. It would only mean pennies per item to consumers, but it would mean billions of dollars to farmers and would eliminate a lot of government spending that consumers are already paying for in taxes. People think raising farm costs means raising the price they pay for food, but the farm cost is just not a big factor in the consumer price. The retail price of a loaf of Wonder Bread has gone up six cents since 1981, but the price farmers get for that same loaf has actually gone down 1.5 cents in the same period.”

The problem, Bunting said, is who controls the prices. “Right now the big corporations are very much in control — that’s what much of the trouble is. We don’t have any control over the prices, and the consumer doesn’t have any control over the prices. That’s why we’re working to get good laws passed. I think the corporations now are so huge that the only thing that stands a chance with them is something else huge—and that’s government. There’s no other way for us to get at ’em. We’d be squashed completely without the government’s assistance.”

Power and Political Decisions

To further strengthen farmers against the combined power of corporate giants, the UFO has forged links with farmers in the Midwest. The emergency haylift during the drought of 1986 had farmers flying back and forth across the country to share their stories and hammer out a common agenda. Today, Bunting serves as president of the National Save the Family Farm Coalition, an organization representing 43 groups in 30 states.

“It’s really been interesting to go into these meetings with farmers from all over the country,” Bunting said. “You have to realize that farming is different in every region. We’ve just been building a relationship where we understand their problems and they understand ours. They’re fighting the same corporate domination we’re fighting.”

UFO President Tom Trantham also speaks of corporate domination — he calls it “the strong taking from the weak.” Trantham was struggling on his 92-acre farm in South Carolina during the drought two years ago when Pete Owenson, an Iowa farmer, heard his plea for help on the TV show Nightline. Owenson offered to lend a hand, and the biggest haylift in history began. Before it ended, train and truck caravans had delivered thousands of bales of hay and 54,000 bushels of seed corn to Southern farmers, and Trantham found himself speaking to standing ovations throughout the Midwest.

“Those Yankees come to me, and you would have thought I was their brother,” he said. “It’s already made a tremendous difference. We meet all over the country and we don’t argue any more — we know we have a common problem. I’ve met with farmers in Montana, Vermont, New York, Iowa, Illinois, and Indiana, and we are taking on the handful of men who run this country.”

Fighting for legislative reform, Trantham said, has changed the way he looks at politics. “You know, 10 phone calls to a senator makes a difference. Did you know that? Before I got involved in this, I would have thought it would take 5,000 or 10,000 phone calls to change a vote. Now I know how it’s done.”

That new awareness — knowing how it’s done, knowing how those in power play the game and how people can unite and bring about change — may be the single biggest achievement of the United Farmers Organization. Out of its accomplishments and cooperation has come a sense that it is possible to organize, that it is possible to take on big corporations and win.

On her farm in the Piedmont region of North Carolina, Edna Harris looked through the congressional testimony and farm bills and newspaper clippings scattered on her dining room table. She shook her head in disbelief and said, “I still can’t believe that things have went like it has. For somebody like me to just be out here on a farm — and I ain’t never been in politics or nothin’. I was a Sunday school teacher, but that was years ago. . . .

“But the UFO changed things right plenty, for me and for everybody. Ask the farmers who they’re going to vote for, they’ll say I’m going to vote for the man who will control the price of bread and milk and butter. That’s another thing the UFO has done. Farmers are more aware of what they need to do in politics, of how they need to get the legislature to work. It’s really made a lot of them more aware of the political situation. That’s how we got in the situation we’re in — we let other people do what we should have been doing, making decisions about our lives. Now we’re organized. Now we’re learning to make decisions about our own lives.”

For more information on the UFO, contact Tom Trantham, president, Rt. 2, Box 244, Pelzer, SC 29669, phone: (803) 243-4801. To learn more about the programs of RAF, contact Kathryn Waller, executive director, 2124 Commonwealth Ave., Charlotte, NC 28205, phone (704) 334-3051.

Net Change in Number of Farms, 1980–1987

Small Farms Medium Farms Large Farms

(Less than ($20,000) ($20,000–$99,000*) ($100,000*)

Down 3% Down 25% Up 5%

% gross annual sales

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.