This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 1, "Unsettling Images: The Future of American Agriculture." Find more from that issue here.

Fifty years have come between us and America’s most popular tale of national crisis,, whereby failure in the financial house of cards and abuse of the fertile plain laid waste to lives, and hands across the land lay idle.

Photographers from the Farm Security Administration were mobilized to record the tragedy. They, along with journalists, film makers, essayists, econo mists and a multitude of artists, went into the interior passionately looking for unpolished truth. It was felt that a good close look into the face of the displaced might so enrage the visceral genius of people that they would be moved to transform society. But bureaucratic objectives prevailed. Government programs were designed to get people back to work, to reestablish the economy. The image-makers provided “evidence” and the photographs were taken at face value.

Photographs no longer carry such authority. New media, more media, and college-trained image-makers bear down hard upon the truth that documentary images pose. Questions of context and rightful voice of the subject may have complicated the innocent assumption that the documentary photograph is evidence of fact, but old habits die hard. When it comes to rural America, image is still predicated upon the notion that prototypal Man breaks the horizon with his feet on the ground and his head in the sky. We like to think of farmers as taking up nature’s gauntlet with grit in their teeth; how then can we imagine the complex truth of their struggle with repayments on overextended obligations?

It remains impossible to determine the voice of rural America from a few photographs and some selected quotes. And yet in the documentary project Manifest Destiny, we have several photographers, a farm advocacy organization, and an arts organization collaborating to promote a greater understanding of the challenges facing America’s food producers. The intent, as seen in the sample of photographs beginning on page 17, is a fresher, perhaps truer vision that awakens audiences to the deeper complexity of life on America’s farms.

Vast difficulties arose in creating the exhibition. Photographers struggled against one kind of mythmaking — and effectively perpetuated the process. In wanting to show how vulnerable and critically balanced the economics and process of food production is — how interdependent we are as a nation regarding the role of the food producer and the consumer — photographers resorted to personalizing the situation. Amidst the romanticized yet very real battling of the elements, the farmer is still confronted with the falling value of his labor against the reality of the new, capital intensive farm — a system predicated on cheap food prices to support consumer demand, pitting the farmer-producer against the system.

Complicating the issue is the diversity of players in the field: migrants, sharecroppers, and tenants, as well as big family farmers attached to collectivized agribusiness, monocultures, and an intervening government bureaucracy. With such unsettling economic relationships, one wonders how the photographer is supposed to take on imaging the problems. On top of this lies the challenge for the photographer in making a meaningful image at all. Today there is so much associated cultural baggage that no image is free to be an “accurate” neutral document.

The photographer must not only recognize the degree to which any image is coded, but also acknowledge that at the instant of its manufacture, a photograph has historicized the situation. As the photographer looks into the face of the farmer, although the subject may face forward, the photographer sees into the past, across the field — the field behind the subject. The subject faces the future, the photographer the past. Here is a rather fundamental difference between nostalgia and optimism.

In its apparent distillation, the context of the event will be further sublimated by gesture, symbol, metaphor and likeness — never continuity. Without the before and after shot, or serial composite, only text may complete the story. To their credit, most of the photographers contributing to Manifest Destiny presented careful documentation. But any text may be applied providing any number of possible meanings. Credibility is tenuous at best. Since most of the photographers selected for the exhibition have been involved with their subjects for long periods of time, their claims to credibility are based on having been accepted by their subjects.

Faced with a wide range of challenges, including understanding his or her own role as producer of consumable images, the photographer must guess against the judgment of the audience. Together they have a compact that trades on an uncompromising demand — to be convincing. Underlying this compact is the unspoken, assumed narrative — a tradition to which the images must refer as if each image were but an episode in an epic drama.

The story begins with humanity cast from the garden — the loss of innocence for which humankind must suffer. In the case of Manifest Destiny, the photographers are also addressing the possible loss of the American garden. As the photographers are challenged, they are also subject to being seduced by their own desire for sentiment, their desire for truth, their desire for meaning. Unbalanced equations have become lore. But no one player has a monopoly on waste and imbalance, or a loss of innocence. Farm folks have been known to spill their milk over a drop in prices. Everyone participates in the system, but the roles are not equal — and the history is not convenient. The people whose lives are currently disrupted are caught in the same process of expansionism that displaced the native American population — in many cases by their pioneer parents.

Encased within the exhibition’s mix of photographic images are symbols of inner conflicts, symbols of a tension between rural and urban, artist and farmer, present and past, male and female, purity and defilement, myth and fact. With such material for the photographer-chroniclers of the current condition of agrarian America, it is no wonder they are compelled to take a stand.

Sponsors of Manifest Destiny

Non-profit organizations interested in hosting the Manifest Destiny exhibition should contact Leslee Samuelson at the Southern Arts Federation, Suite 122, 1401 Peachtree Street, NE, Atlanta, Georgia 30309, phone 404-874-7244. The exhibit includes 50 photographs and requires 167 feet of linear display space.

For more information about the programs of the exhibition’s sponsoring organizations, contact Ken Bloom, executive director, The Light Factory, 119 E. Seventh Street, Charlotte, NC 28202, phone 704-333-9755; and Kathryn Waller, executive director, The Rural Advancement Fund, 2124 Commonwealth Avenue, Charlotte, NC 28205, phone 704-334-3051.

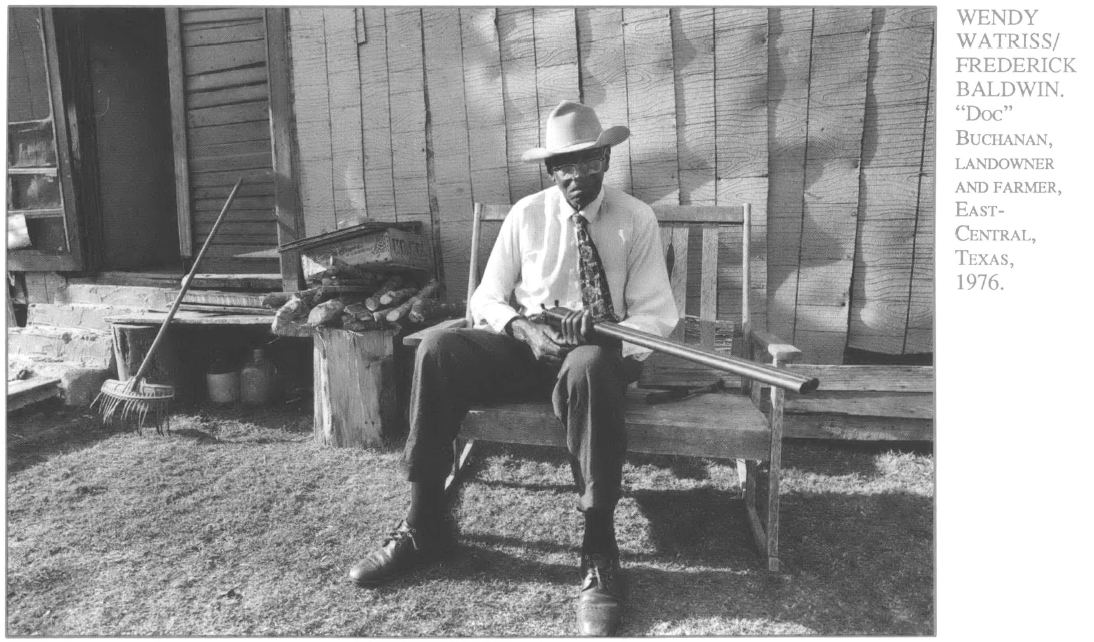

The photographers featured in Manifest Destiny are: Robert Amberg, Durham, NC; Thomas Frederick Arndt, Minneapolis, MN; Margot Balboni, Brookline, MA; Bill Bam¬ berger, Cedar Grove, NC; Tim Barnwell, Asheville, NC; Joseph Bartscherer, Seattle, WA; Stephen M. Dahl, Minneapolis, MN; Robert Dawson, San Francisco, CA; Herman LeRoy Emmet, New York, NY; Carl Fleischhauer, Washington, DC; Bill Gillette, Ames, IA; Frank P. Herrera, Martinsburg, WV; Karen E. Johnson, Brooklyn, NY; Stephen Johnson, San Francisco, CA; Sue Kyllonen, Minneapolis, MN; Les LeVeque, New York, NY; Ken Light, Vallejo, CA; Rhondal McKinney, Normal, IL; Andrea Modica, Oneonta, NY; John Moses, Durham, NC; Thomas Neff, Baton Rouge, LA; Sarah Putnam, Cambridge, MA; Phil Reid, Staunton, VA; Jim Richardson, Denver, CO; Arty Schronce, Raleigh, NC; Stephen Shames, Philadelphia, PA; William Strode, Louisville, KY; Wendy Watriss & Frederick Baldwin, Houston, TX; and Lyle Alan White, Wichita, KS.

The exhibition is made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts through the Southern Arts Federation of which the NC Arts Council is a member.

Tags

Ken Bloom

Exhibition Curator and Director of the Light Factory (1988)