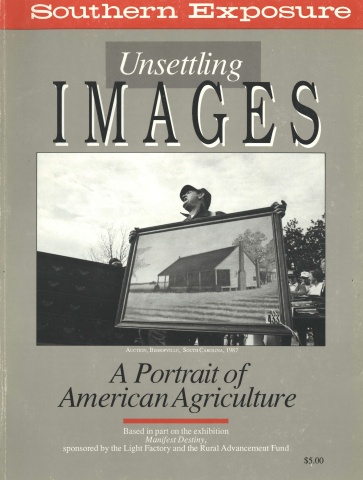

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 1, "Unsettling Images: The Future of American Agriculture." Find more from that issue here.

On May 8,1987, the Rural Advancement Fund of the National Sharecroppers Fund sponsored a Citizens’ Forum in Washington, DC to commemorate the 50th anniversary of an initiative which would be incorporated as the National Sharecroppers Fund. An overflow crowd of friends, supporters, and media representatives packed the U.S. House of Representatives’ Agricultural Committee Hearing Room as Forum participants discussed three issues central to the past and present work of RAF/NSF — family farms, farm labor, and biotechnology.

These seemingly diverse topics are linked by more than their relevance to the RAF/NSF program. Increasingly, farmers and farmworkers — once viewed as adversaries — are finding themselves on the same side of the fence, locked outside the policy councils and corporate boardrooms where crucial decisions affecting agriculture are made.

The Forum highlighted the need for a partnership between these two groups to define and pursue public policies that will give them a fair share of the abundance which their labor brings to our tables. In recent months several groups, most notably members of the Rural Coalition, are rising to meet the challenge of exploring ways in which such a partnership may be forged.

Biotechnology, the “gene revolution,” has grave implications for farmers, farmworkers, and consumers alike. While the Green Revolution affected only major grain crops, biotech products promise to impact every area in the future production of food and medicine. Biotechnology cannot simply be labeled “good" or “bad” — it is here and there’s no turning back. But it is imperative that as citizens we ensure that its development be oriented to meet real and basic needs of society. For example, as Jack Doyle told the Forum panel, “Through genetic engineering, we can develop pest-resistant crops (and thereby reduce our dependency on chemical herbicides) or we can produce new pesticide-resistant crops that increase the marketing of pesticides."

The recent patenting of an animal has grave implications for all of us. Who will own the rights to patented living organisms, and to their offspring? Who will decide what characteristics to add or delete from the genetic code of life? Who will play God?

The substance of the Forum was talk, but its purpose was to spark action — action now, while we still have choices. Implicit in all the testimony and response was the need for each of us, as citizens, to make decisions. As Texas Agriculture Commissioner Jim Hightower, who chaired the Citizens’ Forum, said in his summary of the day’s testimony:

“It seems to me that a common theme running through all of this is that we’re not talking about technical issues here. . . . We’re dealing with moral issues, matters of justice. We’re really talking about stealing. They’re stealing our farms; they’re stealing the labor of our people; and perhaps now they’re trying to steal our future. And ‘they’ are not the outlaws. ‘They’ are the officials — corporate, academic, and governmental officialdom.”

Action is needed in all these arenas, action informed by the moral perspective and humane policies conveyed through this testimony and the Forum overviews reprinted on pages 12 to 14.

— Kathryn Waller Executive Director, RAF/NSF

Members of the Citizens‘ Forum included (top row, left to right) J. Benton Rhoades, executive director for the Committee on Agricultural Missions of the National Council of Churches; the Most Rev. L.T. Matthiesen, Catholic Bishop of Amarillo; Helen Vinton, a rural specialist with the Louisiana-based Southern Mutual Help Association and RAF/ NSF board member; Hubert E. Sapp, executive director of the Highlander Research and Education Center in Tennessee; Dan Pollitt, law professor at the University of North Carolina and RAF/NSF board member; Jim Hightower, Texas Commissioner of Agriculture and presiding chair for the hearing; Barbara Bode, director of the National Agenda for Community Foundations; and Baldemar Velasquez, farmworker-founder of the Ohio-based Farm Labor Organizing Committee.

RAF/NSF board members seated below the panel are: Rowland Watts, retired attorney and Workers Defense League co-founder; Gonze L. Twitty, South Carolina saw mill owner and president of the Southern Cooperative Development Fund; Dr. Charles Ratliff, Jr., economics professor at Davidson College in North Carolina; Rev. A. H. VandenBosche, retired Presbyterian minister and National Farm Worker Ministry board member; Robert Miles, Mississippi farmer and civil-rights activist; and Fay Bennett, NSF/RAF executive director from 1952 to 1970.

The Family Farm

The first panel of witnesses provided a sobering analysis and a moving personal portrait of the state of family farm agriculture today.

Helen Waller, Montana grain farmer and president of the National Save the Family Farm Coalition:

The family farm system of agriculture is threatened with extinction in America. More than 2,000 farm families are being forced off the land every week. Communities which once bustled with activity are being boarded up, with schools and churches no longer able to function for lack of people and money. The wealth of these communities has dried up because of national farm policy which allows farm production to be purchased by grain merchandisers at far below the cost of production, with deficiency payments to farmers failing to make up the difference.

The administration’s market-oriented policy with its goal of getting the government out of farming is the blueprint for delivering our food-producing land into the hands of insurance companies, speculators, and the landed elite.

The assumption that there will ever be a “free market” for the transaction of grain commodities is a myth. In reality, it makes no difference to what facility a load of grain is delivered — local elevator, flour mill, or barge loading point. In each case, the price paid the farmer by the grain handler comes from a quotation off the Chicago Board of Trade, with an adjustment for transportation. There is no competition out there for our product. At this point, only the price support established in farm legislation can force the grain trade to bid up in order to get our grain. That price support gives us the option of borrowing against the value of our commodity from the federal CCC [Commodity Credit Corporation] at whatever price level the legislation dictates.

The loan level for wheat was set at $3.30 a bushel at the time John Block was Secretary of Agriculture. But the 1985 farm bill gave him the authority to drop that rate. And right before he left, he did just that — he dropped the loan rate to $2.40. So the market price set by the grain trade immediately fell to meet that level. Traditionally, the loan rate set by the government sets the market price because that’s their only competition.

So when it dropped from $3.30 to $2.40, that left us with a 90-cent deficit that had to come from the taxpayers’ pockets [through “deficiency payments” provided in farm legislation]. And that’s what made the farm program so extremely expensive. Instead of forcing the grain purchasers to pay $3.30 a bushel, it shifted the burden directly on the taxpayers. And I’m saying that’s wrong. Let the grain trade pay the value of the commodity, not the taxpayer. The taxpayers are now subsidizing grain processors.

Some say, “We have to export more grain.” The present administration has consistently lowered loan rates — and consequently the market price — in an effort to be more competitive on the world market. But despite the low prices, foreign producers sell on the world market at just below whatever price the U.S. establishes.

What has this accomplished for U.S. grain farmers? Economic disaster. Since 1980, under a program of lowering loan rates, the United States has lost 50 percent of its export market, which represents a 58 percent drop in value. The present farm program of lower commodity prices is working counter to what the administration had anticipated, and at the same time is driving family farmers off the land.

This activity denounces one of the most basic principles on which this country was founded — the widely dispersed ownership of land. America will be weaker if farm operators are no longer owners of the land they work.

The only way to reverse this trend is to replace the failing farm policy with a plan to restore economic and social justice in rural America. This plan has been formulated, beginning with hearings throughout the countryside where farmers have spoken out for price supports, supply management through farmer referenda, and parity — the return of the cost of production plus a reasonable profit at the farm level. This is the Family Farm Act, introduced by Congressman Dick Gephardt and Senator Tom Harkin.

Let me just add that I have a 20-year-old son who is now looking toward a future on the farm. The only way to reverse the outward flow of the farmer is to bring profitability back to the farm sector at the production level, at the level of the individual small farmer. When that happens, there will be plenty of incentive for young people to again enter the farming business. One of the bigger national tragedies we have now is the outward flow of some of the most educated, most efficient farmers on this land. And we will not, as a nation, be able to replace those people overnight. They won’t come from the textbook setting of economists with their flowery speech about how the farm should be farmed. These will have to be dirt farmers that know the land and understand what it means to plant that seed and nurture that crop to maturity.

Tom Trantham, dairy farmer from Pelzer, South Carolina, and president of the United Farmers Organization:

The family farmer is the man in the community who may go to town in a beat-up truck, but will have the most beautiful cows or a corn field with rows straight as an arrow. This is our pride, our quality, our Cadillac.

Farmers are working too hard, and not telling you — the American people — the real problems we’ve got. But now we have to. I’m ashamed to be here, and I’m ashamed to let you know what my financial situation is. I’ve worked all my life. I’ve condemned people that had financial situations like my own now. A few years ago, I had $200,000 equity in my small family farm. Today, I’m $200,000 in the hole. I can’t walk into a bank, much less borrow any money from one. And I’m ashamed of that.

Just a couple of months ago [February 1987], I received the first check from the 1986 drought relief that the federal government put through. Ladies and gentlemen, my cows had only three weeks of feed left in July 1986. I had made the decision to part with my farm. I could not see my cows starving. In the drought of ’83, a friend of mine tried to hold on — and his cows actually died on his farm. I made a promise to myself after seeing his cows that I would never let that happen.

In the drought of ’86, I was ready to disperse our farm, and my family and I would have been packing our bags to leave our home. But the American people — not the government — turned that around. They brought salvation to my farm. Through the “farmer-to-farmer haylift” (see page 9), they brought what it took for us to survive. Today my cows are doing well. We’re now harvesting South Carolina feed. It’s a great pleasure to have fed them corn and hay from Iowa, Michigan, and Illinois — and the cows enjoyed it. But today we’re feeding them South Carolina feed, and it’s quite a pleasure.

Now then, that federal program money is going to help. It’s going to help me buy the feed and seed to plant this year’s crop and to continue on. But there was no way I could have survived the drought with my own resources or waited for the federal check that was due several months down the road.

If parity was at the farm level, we would have lost the crop of ’86, but there would have been a profit in ’85. There would have been a little nest egg, a savings account, or at least credit for us to fall back on. You can always tell a good year — a farmer will go out and buy a new pickup. And they will wear it out over the next five years, because the next five may not be too good. We’re used to that. We can live with that kind of life.

Give me parity at the farm level, and I may buy a new pickup once in a while, but if a drought comes or the army worms hit my crop, I will be able to live through that. I think that says that God won’t put more on us than we can bear — but I don’t know about the government.

American agriculture is very profitable the instant it leaves the farm, but not a minute before. While farmers were helping farmers survive the most severe drought in 100 years, Cargill rolled up a 66 percent profit increase. The president of my own dairy co-op received a $50,000 raise during the same time we were struggling to feed our cows.

Four years ago you paid $1.89 for a gallon of milk and I received $1.23. Today you pay $2.43 per gallon and I receive $1.14.

Each year the supply goes up, but the price goes down. So our only alternative is to increase production again and again. Farmers can survive natural disasters, army worms, droughts, and boll weevils easier than they can survive federal policies aimed at putting us off the land. We have been forced to farm beyond our facilities and abilities. For instance, in the early 1980s I expanded my herd from 80 cows to 120, and believe me I went broke. My facilities are only capable of handling 80 cows. Increasing to 120 cows reduced my efficiency tremendously. My production dropped from 18,000 pounds of milk per year to 15,000 pounds.

George Ammons, a turkey farmer from Duplin County, North Carolina, and member of the United Farmers Organization:

I grew up on a farm, and now operate my own farm. It has proven to be a disastrous feat for me and my family. I inherited 150 acres free and clear. In order to make a living, I mortgaged the land to build four turkey houses. Like other black farmers, I could never get a limited-resource loan or any other low-interest loan, because we black farmers were not informed of the programs that were there for our benefit. Black farmers in the rural South have been in a continuous crisis for the past 50 years, like while farmers are in now. We not only have faced the general decline in farm economy, but also neglect, racial discrimination, and economic exploitation.

When we did learn of our rights and opportunities and asked for them, the loan officers would always find excuses to refuse our applications. Those of us who were able to get loans were forced to take them at the highest interest rates. Most black farmers could not get loans at all and operated on just what cash they had or could get from family or friends. We have had to lease enough acreage to make a living. Many black farmers have been unable to add to the 25 or 40 acres they inherited in the 1800s.

I testified before the U.S. House Subcommittee on Civil Rights in 1984. Their own report documents an unequal distribution of agricultural credit and the denial of due process in obtaining farm ownership and operating loans. A report by the U.S. Civil Rights Commission in 1982 warned that unless lending policies at the Agriculture Department were changed, there would be no black farmers in the U.S. by the year 2000. That trend has not slowed because lending policies have not changed.

Experts agree that blacks are losing land at an annual rate of 500,000 acres. This is 2.5 times faster than white farmers. Black farmers once owned over 15 million acres of farmland in the U.S. but today we own less than 3.2 million acres according to the 1982 U.S. Civil Rights Commission. In Duplin County there are 232 black farmers who operate over 7000 acres of land and most of these farmers are on the brink of disaster. And at the same time, there are only 181 black farmers under the age of 25 in the United States. If this current trend continues, blacks will be a landless people within the next 10 years. The loss of its land base will be devastating to Black America.

Like all family farmers we are the victims of low prices, high interest, tight credit, and natural disasters. And while fair prices and sensible farm policies would help us just as it would others, we do face extra problems due to years of discrimination. The research has already been done. We need to go ahead and solve the problems now. I recommend that:

— FmHA should be required to use its limited-resource, lower interest loan funds to provide operating and ownership loans to blacks and other truly limited-resource farmers as it was intended to do. Or a new special fund should be set up for this purpose.

— The Farm Credit System should also establish a special low-interest loan fund for blacks before any bailout occurs.

— A special watch-dog commission to oversee all USDA programs should be set up. This commission should have the power to collect data and to publicize regularly on a county-by-county basis the distribution of benefits of USDA programs by race. It should have the authority to investigate violations and discrimination on site rather than in Washington.

— More blacks should be hired, promoted and appointed to important decision-making committees within USDA.

— Special extension agents for each county with the sole responsibility of assisting black and other limited-resource farmers should be funded. This includes enlarging the current 1890 land grant college small farmers programs.

— Any time limits are set on the amount of debt or equity a farmer must have to qualify for programs, the situation of black and other small-acreage or low-equity farmers should be taken into account. For example, the 1985 Farm Bill set a minimum of $40,000 per year in sales for a borrower to qualify for FmHA protections. This leaves out many black and small farmers.

— As thousands of acres of farmland are taken into inventory by Farmers Home and the Farm Credit System, this land could be redistributed to blacks after the previous owners have had first chance to buy or lease back the land. A priority should be set on giving blacks opportunities to acquire this land and thus offset some of the devastating land loss.

As taxpayers, we have paid our fair share for USDA programs, but we have not received our fair share of the benefits.

Wendell Berry, Kentucky farmer, author, and poet:

It is not just the needs of the farm people that should determine agricultural policy, but also the needs of the farm land. A wise agricultural policy would seek out and foster those accommodations by which the interests of farm land and the interests of farm people cease to be competitive interests and become the same. If these two interests are reconciled, then the legitimate agricultural interests of urban people — permanent, healthy supplies of food and water — will be met as well.

Much of the farmland of the United States is extremely vulnerable to erosion, and it therefore requires extraordinary concern and skill of its users. In general, the more marginal and vulnerable the land, the less it has repaid care, and the less care it has received. At present, almost none of the farmland in our country is paying its users enough to take proper care of it. The result is serious and sometimes severe soil loss and soil degradation.

A related problem is the pollution of our soil and water by agricultural chemicals. In terms of land use and land-use policy, these substances must be understood as labor substitutes or labor replacers. The evils of erosion and pollution signal the decline of the farming population, both in numbers and in the necessary devotion and skill.

Almost every agricultural problem that we have is either caused or made worse by overproduction. Overproduction, in turn, is caused by the economic individualism, the wide dispersal, and the disarray of the farm population, abetted by advances in plant breeding and in chemical and mechanical technology. Overproduction is now widely recognized as a destroyer of farm families and communities; that it is equally destructive of land has, so far, been less noticed or less acknowledged. Production control, of course, is the obvious and the proper solution, and production control is properly the work of the federal government, since that is the only organization that includes all potential competitors.

The goal of a sound agricultural policy would be to increase gradually the number of family livelihoods in farming until we have enough people on the land, not only to make it produce, but to give it the good care that it needs and deserves. To divide the usable land among as many owners as possible, given the requirements that the use of land implies an inescapable necessity to care for it, would be good for agriculture, good for the people, good for democracy, good for the land, and good for consumers.

To such an agricultural policy there will be three objections: (1) that it would impose checks and corrections upon the working of the free market; (2) that it would obstruct the further development of large-scale industrial agriculture, which has long been the chief aim of the agribusiness corporations, the agricultural bureaucracy, and the colleges of agriculture; and (3) that it would increase the cost of food.

The answer to the first objection is that the so-called free market is responsive only to the most immediate economic objectives. It cannot define or respond to the long-term requirements of the land, the users of the land, or of the consumers of the land’s products. It cannot, that is, define or enforce the requirements of a responsible land stewardship.

The answer to the second objection is that large-scale industrial agriculture, with its industrial aims and standards, is the chief cause of the present problems in rural America. Large-scale industrial agriculture has failed, and its failure is written incontrovertibly in the statistics of soil erosion, soil pollution, ground water pollution, aquifer depletion, bankruptcy, family failure, and community death.

The answer to the third objection is that it will not increase the cost of food in the grocery store by much, and that it will greatly reduce its environmental and human costs. “Cheap food” is not cheap when it is paid for by the ruin of land, families, and communities. The food industry, in the midst even of the present farm depression, remains enormously profitable to agricultural suppliers, and to the transporters, processors, advertisers, and marketers of food. In view of this, is it not more than bad faith to object to a decent increase of earnings to food producers?

Betty Bailey, director of RAF’s Farm Survival Project and author of the policy statement on page 12, summarized the choice confronting every citizen of this country regarding the fate of the family farm:

We can continue present government programs which reward greed and worship excess, exploiting family farmers, taxpayers, and consumers while encouraging the destruction of our precious soil and water resources; or we can implement policies to support and enlarge our pool of small and mid-size independent farmers, providing incentives for competitive and innovative family farm entrepreneurs. We have a choice.

The Farmworkers

The testimony of the second set of witnesses shifted the hearing’s focus from the family farmer to the thousands of farmworkers who spend their lives harvesting many of the foods that appear each day on American tables and whose lives are still threatened by unjust, hazardous, even lethal, working conditions.

Roger C. Rosenthal, executive director of the Washington-based Migrant Legal Action Program (MLAP):

There have been changes for the better for migrant farmworkers in the 50 years since the National Sharecroppers Fund was established. There have been some positive changes even in the past 25 years. But that does not take away one bit from the fact that the present status of migrant farmworkers is still abysmal. It is, in fact, a national disgrace.

I have seen the small one-room shack in Orange County, New York, one hour from New York City, which stands, unattached and unanchored, on stone pilings and which literally lifts off those pilings, tilting to one side, when the worker who lives there moves from one end of the room to the other. I have heard the story of the public health nurse who worked with farmworkers in labor camps in North Carolina, a woman who thought she had lost her capacity for shock, having found terrible medical conditions among her patients including active cases of tuberculosis. One day she had to change her scheduled visit to a particular labor camp. She arrived, unannounced, early in the morning just in time to see the camp crewleader put the guard dogs away. She had not known that her patients were literally held captive at night in their labor camp.

Well, you might say, there are federal laws to protect these workers. But let us take a moment to look at some of these laws.

The Fair Labor Standards Act which mandates a minimum wage and prohibits child labor was passed by the Congress in 1938 — but it took 30 more years for farmworkers to be covered by the law. Even so, two-thirds of all farmworkers are still not covered because threshold requirements make it applicable only to larger employers. It took ten more years, until 1977, for farmworkers to obtain the same minimum wage level as other workers. And in spite of the fact that farmworkers toil long hours in the fields, sometimes 12 hours or more a day, they are still not entitled to overtime. Moreover, the extent to which employers do not comply with the minimum wage is shocking; so is the sorry enforcement record by the U.S. Department of Labor.

Working conditions covered by federal statutes are also not enforced. Crew leaders routinely misrepresent the conditions of employment, which workers only discover after being taken hundreds of miles from home. There are also problems of housing, transportation, pesticides, and safety that come up daily throughout the country.

The National Labor Relations Act, which covers more than 40 million workers across this nation, does not apply to farmworkers. Therefore, the struggles of all worker groups to achieve contracts and union recognition from employers are truly modern-day versions of the tale of David and Goliath. The successes of these worker groups against the huge corporate interests in agriculture are successes against absolutely overwhelming odds.

And then there is the story of field sanitation — the 15-year fight to obtain the right to a toilet, handwashing facilities, and potable drinking water in the fields. In principle, the Occupational Safety and Health Act protects farmworkers’ rights along with non-agricultural employees. Yet in the early ’70s, the Department of Labor failed to act on a petition by farmworkers to promulgate a field sanitation standard. That standard, which was finally issued one week ago on May 1, took 15 years to obtain, including a full trial and several appeals to the U.S. Court of Appeals which finally ordered the Department of Labor to issue the standard immediately. And yet the standard, due to Congressional restrictions, still does not cover 80 percent of farmworkers. These workers remain unprotected, subjected to the daily indignities of squatting in the fields, dehydration, and exposure to toxic pesticides without the ability to wash them off.

To make matters worse, the current federal administration has targeted farmworker programs for massive cuts or extinction. In budgets submitted to the Congress, it has requested substantial cuts in the Chapter 1 migrant education program, substantial cuts in the FmHA farm labor housing program, and extinction of the tiny but important High School Equivalency and College Assistance Migrant Programs.

The presidentially appointed board of the Legal Services Corporation has specifically targeted migrant legal services programs for large cuts or extinction. My agency, the Migrant Legal Action Program, has just fought off an attempt by the Legal Services Corporation to defund our program. The Corporation has threatened to cut the Texas farmworker program by threequarters, despite the fact that its figures show a three-fold increase in migrant farmworkers and dependents over the past ten years.

Another serious problem on the horizon is the impact of the new immigration law on farmworkers. Domestic U.S. workers, in as yet untold numbers, may lose their jobs to imported foreign workers. And the actions of the Immigration and Naturalization Service and the U.S. Department of Labor in implementing the new statute are extremely discouraging to farmworker advocates.

A lot of people don’t understand that migrant farmworkers don’t seek government help and don’t come to our offices as clients in an urban setting do. Legal Services paralegals and attorneys have to go out to the labor camps to let people know their services are available.

Because of the lack of control that farmworkers feel about their lives and their economic situation, they are very afraid of rattling the cage or of seeking assistance. They know that if they do, they may not get the job the next year, and even though it doesn’t pay them the minimum wage, it’s the difference between their children having clothes and starving. They don’t want to lose the little that they have.

Farmworkers must be brought out from the shadows into the light of day. This country must confront its obligations to help people who are the key to our economy and our well being. We must not turn our backs on those who are poisoned by pesticides, denied decent housing and who suffer the indignity of terrible wages and working conditions. We must rededicate ourselves to sustaining the hard-working men, women, and children who sustain us through picking the food we serve on our table every day.

Sister Evelyn Mattern, representing 25 denominations within the North Carolina Council of Churches:

North Carolina, where I come from, has the third largest number of farmworkers in the country. There are approximately 100,000 seasonal farmworkers who live in our state year-round, and another 60,000 migrants who come from Florida, Texas, or the larger East Coast cities to help with the planting or picking of tobacco, sweet potatoes, cucumbers, peppers, and other vegetables. Seasonal workers in North Carolina tend to be black American families; migrant farmworkers are generally single black males traveling in crews or Hispanic families traveling in extended family groups. There are also smaller numbers of Haitians, Cubans, and Central Americans.

Unlike the very large migrant labor camps one sees in other parts of the country, farmworkers in North Carolina typically live in small cinder block camps, groups of trailers, old pack houses, tenant shacks on the farmer’s land, old tobacco barns, and — increasingly — in independent housing that they find in the towns near where they work.

The treatment of farmworkers in North Carolina is best understood by remembering that we are a former slave state. There have indeed been ten slavery convictions against crew leaders in our state in the last six years, and I myself have taken men from camps who tried to escape and were bloodied and beaten in the attempt. As a measure of altitudes that persist, our state legislature declined to pass a state anti-slavery law in 1983, largely because of intense lobbying against it by the North Carolina Farm Bureau.

Nevertheless, it may be that the most pervasive and persistent slavery today is not the kind that relies on guns and whips and vicious dogs. Economic slavery destroys as much human potential from generation to generation as did the legalized slavery of the Old South. Economic slavery is based on piece work and “debt peonage,” whereby half of every dollar earned goes to the crew leader, who then deducts further exorbitant amounts for travel, housing, meals, cigarettes, alcohol, and (now, increasingly) drugs. By the end of the season, the soul of a whole family may be owned, as Tennessee Ernie Ford sang it, by the “company store.”

Much of this economic slavery is legal. In our state farmworkers have no rights to worker’s compensation, overtime pay, collective bargaining, freedom from invasion by pesticides, or even visitors in their employer-owned housing. Because of lack of enforcement of laws that do exist, farmworkers are practically excluded from minimum-wage laws, unemployment insurance, social security benefits, and alcohol, drugs, and firearms laws, and child labor laws. Agriculture is the third most dangerous occupation in our country, and farmworkers have twice the rate of hospitalization as the general public. But the “agricultural community” — in our state, defined solely as farmers — remains unique in deferring the entire cost of medical care for farmworkers onto the taxpayer. Our state legislature is right now in the process of vigorously rejecting inclusion of farmworkers in worker’s compensation laws because the costs of such coverage would be, as one legislator said to me, “the last spike in the farmer’s coffin.”

In the Old South, although the entire economy depended on the labor of slaves, their reality as persons was denied. They had to be invisible for the system to survive. It is the same with farmworkers today. The makeshift tobacco barns, tenant houses, and trailers that serve for their shelter are far from the main roads. Health inspectors can’t find them, and sheriffs don’t want to.

Agencies don’t have data on farmworkers. Try to find out how many there are, where they are living, which farmers use them, what pesticides they are exposed to, what injuries have been sustained, what the various agencies define a farmworker to be. You end up agreeing with Truman Moore who wrote in 1965 in “The Slaves We Rent” that our government knows more about migrating birds than migrating farmworkers.

This failure to keep accurate records of migrants and their living conditions is no accident. Right now, the North Carolina Council of Churches — for which I work — is suing the Farmers Home Administration over this issue. That agency has unspent money for farmworker housing programs, and our state has ten counties designated by the agency as areas of high need for these programs. When we applied for some of that money, we were told that there was no need and no demand. We are outraged, but we realize that the reason we have been denied is that we had the temerity to buy a piece of land for housing that is on a main road, near a town, with access to grocery stores, school bus stops, and middle-class white people.

To break this modem system of slavery, I recommend the development of:

— comprehensive federal and state policies that include farmworkers in agricultural programs, rather than the current proliferation of federal and state agencies using too little money to work in fragmented ways;

— far-reaching agricultural policies that encourage small-scale farming, local markets for farm products, and the drastically reduced use of herbicides and pesticides;

— full coverage of all farmworkers in state and federal labor, health and safety, insurance, and housing laws, and vigorous enforcement of these laws;

— church and privately sponsored programs that put attorneys, organizers, and leadership development trainers into the field to assist farmworkers, much as the church has done in support of migrant social workers; and

— a hemispheric economic policy that invests U.S. dollars in small-scale development projects in Mexico and the rest of Latin America. As long as U.S. foreign policy dollars in the region go primarily to support repression, we will continue to see a flow of people from there to here. You can’t build walls high enough, nor man enough guns, to stop hungry people who have nothing to lose.

Biotechnology

The third area focused on by the Citizens’ Forum represents a new presence in agriculture — biotechnology or the engineering of living organisms to make or modify products. But, as Jim Hightower said in introducing the witnesses, this new technology hinges in many ways on “an old issue of the preeminence of science, bureaucracies, and corporate systems over people and human institutions.”

Jeremy Rifkin, founder and director of the Foundation on Economic Trends in Washington, DC:

Let me try to place this biotechnology revolution in context. The world economy is making a long-term transition out of petrochemical-based resources into biological resources. Similarly, we’re moving out of industrial-based technologies into biotechnologies. There is a very big question mark about how we’ll organize the Age of Biology as we move into the twenty-first century.

There are two broad philosophical and technological options. On the one side, we have ecologically based technologies, a science based on empathy with the environment and stewardship of our natural resources. On the other side, we have a reductionist-based technology that intervenes in the genetic code and the blueprints of living things.

I can best express it by way of two images. If you open up a chemical trade magazine, you will see envisioned there twenty-first century farms where animals are chemical factories, where the chemical and pharmaceutical companies control the entire process, and where agriculture is reduced to industrial technology and industrial terminology.

I saw another image of the farm future eloquently expressed in the Washington Post a few months ago. It was a news article about a Midwestern farm which, in the 1970s, had gone over from petrochemically based agriculture to organic agriculture. It had diversified its crops, it had moist soil, and was doing well. Surrounding that farm were farms that looked like they were embedded in poison, with chemicals, pesticides, and fertilizers. The one farm was doing quite well with minimum energy inputs and was producing quality crops while the farms around it were going out of business.

I think it’s naive and disingenuous for the chemical industry to say we have only one future — biotechnology. I do not believe that biotechnology is a fait accompli for us in the twenty-first century. It will depend on the will and vision of citizens around the world as to what kind of future they want.

Let me go into several aspects of biotechnology which dramatically illustrate the problems we face; but let me also preface this by saying that the basic assumptions of biotechnology exacerbate all the problems of the Green Revolution: We’re going to have increased monoculturing and loss of gene diversity because, by its very nature, genetic engineering is designed to streamline plant and animal species more quickly than classical breeding techniques can. And we will see the loss of soil nutrients. Biotechnology aims to imprint efficiency into the genetic codes of plants and animals so we can grow more in less time. But from nonequilibrium thermodynamics we know there’s no such thing as a free lunch. You cannot continue to accelerate the production of biologically useful utilities without depleting the nutrient base.

Let me give you three examples of problem areas. First, there is the regulation of genetically engineered organisms that will be placed on our farmland on a massive scale. You probably know that the first genetically engineered microbe was released recently in a plot of California land after a four-year regulatory and court struggle. The chemical, pharmaceutical, and biotech companies are talking about introducing scores, then hundreds, then thousands of genetically engineered viruses, bacteria, plant strains and animal breeds into our commercial agricultural system. That’s the scale we’re talking about. Dupont is to set up a $200 million life science complex and Monsanto a $150 million complex. Right now we introduce thousands of chemical products each year, and not all of them are safe. Imagine introducing thousands of genetically engineered bacteria and viruses. It strains the imagination to believe they will all be safe.

Next, we have the Bovine Growth Hormone (BGH), a classic example of the problems with this technology. We’re producing too much milk in this country, yet the chemical companies come up with the BGH which will increase milk production, throw thousands of farmers out of business, and further degrade the rural communities of this country — just so there can be some profits for Upjohn, Eli Lilly, Monsanto and some other companies. But we don’t believe that the BGH is a fait accompli either. We have a coalition building here and in Europe; we plan a nationwide and international boycott in the next year. We’re going to ask families all over the world whether they want to have milk from cows injected with the BGH.

Finally, let me raise one more issue — animal patenting. About a week and a half ago the U.S. Patent Office said that all forms of animals short of homo sapiens can now be patented, even animals with human genes functioning in their genetic codes. This has tremendous ethical implications. Here’s a handful of government bureaucrats who have arbitrarily redefined life. They said in their patent decision that living things are “manufactured products” and “compositions of matter” indistinguishable, for all intents and purposes, from toasters and tennis balls.

The impact on animal husbandry is going to be devastating. Imagine a new form of tenant farmer in the coming decades — not only are they going to be leasing their land, they’re going to be leasing their animals, too. And every time a patented animal gives birth, they’re going to have to pay a royalty. When they sell their herds, they’re going to have to pay royalties. If you’re a dairy or hog farmer or a cattleman, this is the kiss of death.

One last point: Opposition to genetic engineering is building and it cuts across traditional ideological boundaries. This isn’t a rightwing-leftwing question. It poses a whole new spectrum — sacredness and respect for life versus utilitarianism. We have animal welfare organizations joining with national farmer groups against the patenting of animal life. In the Baby M case and other issues, feminists are finding themselves sharing some sentiments with people in the right-to-life movement. We have conservative Christians joining with environmentalists. I think the Age of Biology is creating new alignments where constituencies can come together regardless of old wounds and old histories.

This is a particularly strong international effort as well. Over 140 organizations from all over the Asian continent recently came together for a conference in Malaysia. Among other things, they passed a resolution advocating a total moratorium on all genetic engineering until a risk-assessment science can be developed. And they said they don’t want any dumping of genetically engineered products in the Third World. Instead, their resolution called for research and study for sustainable agriculture futures. I think that we in this hemisphere have to move together with our European, African, and Asian friends and develop a worldwide movement to oppose aspects of genetic engineering technology and to favor new organic approaches to agriculture for the next century.

Jack Doyle of the Washington-based Environmental Policy Institute:

The definition of biotechnology that farmers, farmworkers, and others should insist upon is the broadest one possible; one that embraces what I call “common sense genetics.” We should not become so enamored of agricultural biotechnology that we go out of our way for a high-tech solution when a common-sense alternative is right in front of us.

If we use this new biology only to divide up the natural world into its smallest possible commercial parts — that is, if we use this knowledge only to patent the genes of nitrogen fixation or photosynthesis to make products, rather than improve our ability to work with the biological realm — we may only create further economic and environmental problems for the future.

But biotechnology does provide us with some new tools and some new opportunities. Let me offer you one possibility: I believe it would be possible to drastically reduce, if not totally eliminate, the use of pesticides in agriculture by “building-in” disease and insect resistance into crops and livestock with the help of biotechnology.

Certainly, we have increasing public concern over the use of pesticides in agriculture, pesticide residues in food, groundwater pollution, and farmer/farmworker poisonings. Why not use the opportunity of biotechnology to call for a major national program in disease and insect resistance research that would eliminate the need for pesticides in agriculture? One could look at this as a kind of “preventative medicine” or a pro-active public health strategy.

I believe such a program would elicit widespread public support and accomplish several things simultaneously. First, it would reduce public, farmer, and farmworker exposure to pesticides. Second, it would reduce the cost of production for farmers and thereby improve farm income and profitability. Third, it should improve consumer faith in the agricultural system and possibly reduce prices once all associated “pesticide costs” were reduced through the system. And fourth, it could provide a powerful basis for rejuvenating the land grant universities and agricultural experiment stations.

Part of the reluctance to pursue this kind of research in a major way dates to the discovery and widespread use of cheap and abundant pesticides, antibiotics, and animal drugs that became available at the end of World War II. In this country, we were doing a lot of good disease and insect resistance research at the turn of the century and on into the 1930s. But there was a powerful disincentive to continue this research as the chemical and pharmaceutical approaches gained precedence and the genetics of yield became the exclusive focus. While the new biology has the potential to move us out of the chemical pesticide era, some troubling developments may preclude society from pursuing this opportunity.

We know, for example, that there are more than 30 companies exploring ways to give crops the genetic wherewithal to resist chemicals, not pests — and thus subject them to the application of more herbicides. U.S. Forest Service researchers are exploring ways to make forest trees resistant to herbicides. Others are considering ways to give honeybees genes to make them resistant to the side effects of certain insecticides. And still others are exploring ways to make chemical growth regulators serve as prompts or signals for turning genes on or off in crops and livestock.

The net effect of such research will be to further entrench the chemical and supplement approaches in agriculture. Such approaches will likely prove to be increasingly expensive, inefficient, and environmentally damaging when compared to using “built in” genetic resistances and other common-sense biological strategies. To prolong the old and outdated chemical and supplement approaches in agriculture with biotechnology is, I believe, going the long way around the barn. Today’s new biology gives us a chance to be smarter and safer.

The potential for biotechnology to broaden agricultural opportunity and improve public health and safety will be eclipsed if the technology only becomes a vehicle for further economic consolidation. Quite simply, genes are becoming a substitute for labor and resources in agriculture, and thereby a powerful ingredient for economic consolidation throughout the food system. The Congressional Office of Technology Assessment prepared a report last March which says the net effect of biotechnology will be to cut in half the number of farmers we now have. “Of all the technologies coming to agriculture,” the report says, “the biotechnologies will have the greatest impact because they will enable agricultural production to become more centralized and vertically integrated.”

The old lines that separated chemical, pharmaceutical, seed, and energy companies are becoming obsolete in this new age because DNA, the genetic code of life, is the common raw material in all their undertakings. A handful of companies now control the world’s chemical crop industry; these are also the major pharmaceutical firms, and the plant breeding companies. They are the companies that will be the leading biotechnology companies. These are life science corporations using DNA as their raw material.

How do you make a technology like this — one that can be lodged in so few hands — accountable? We must insist that this technology is accessible and broadly available — and that involves a strong public sector presence. That is why pursuing projects like disease and insect resistance research are in the broad public interest and serve as a spur to, and a check upon, the private sector.

Dr. Susan Wright of the University of Michigan illuminated the military applications of biotechnology:

It would be a tragic reversal if the agricultural pests which farmers and farmworkers have worked so hard to control are given new life by the military establishment as weapons to destroy crops. Biological weapons are organisms — viruses, bacteria, fungi — that are used to cause death or disease in people, animals, or plants. During and after the second world war, extensive research and development efforts in many countries, including the United States and the Soviet Union, transformed biological weapons from crude instruments of sabotage into weapons of mass destruction. Fortunately, biological weapons have not been extensively assimilated into military systems, but specialized uses against economic or other strategic targets like agricultural crops or forests may be envisaged. The monocultures of modem agriculture are particularly vulnerable to biological warfare.

As a result of strong international and domestic opposition to the development of chemical and biological weapons in the 1960s, recourse to biological warfare is prohibited by an extensive international legal regime. The 1972 Biological Weapons Convention — the most extensive disarmament treaty in existence — prohibits development, production, and stockpiling of biological and toxin weapons. The 1925 Geneva Protocol prohibits use of biological as well as chemical weapons. The United States, the Soviet Union, and most other major states are parties to these treaties.

In theory, then, the threat of biological warfare should have been eliminated. However, in recent years, particularly since 1980, there have been renewed grounds for concern.

First, biotechnology provides the means not only for enhanced control over the behavior of living things but also the ability to construct novel organisms and substances. A Pentagon report released last year claimed that exotic new bioweapons are now within reach of industrialized nations and even those that are less developed.

Second, since 1980, the Reagan Administration has repeatedly accused the Soviet Union of violations of the biological warfare legal regime. In each instance, however, the evidence for these charges has turned out to be tenuous. For example, the “yellow rain” claimed by George Schultz as a “lethal toxin weapon” developed by the Soviet Union for use by the Vietnamese turned out to be nothing other than the feces of Southeast Asian honeybees. The Reagan Administration has not received support for its allegations from any other nation, but these charges have helped persuade Congress to increase appropriations for chemical and biological warfare programs.

Third, since 1980, there have been steep increases in spending on the Chemical Warfare and Biological Defense programs. The request for fiscal year 1987 of $1.44 billion is 554 percent of 1980’s level. Support for research and development for these programs is projected at $220.4 million — an increase of 400 percent over FY 1980. In real terms, spending now exceeds the highest levels of the 1960s when an active chemical and biological warfare program was being pursued.

Many of these new military research dollars have a heavy emphasis on biotechnology. Eighteen government laboratories and over 100 universities and corporations are involved in this work. In 1984, there were over 100 projects in biotechnology sponsored by the chemical warfare and biological defense program.

Most of this research is “defensive” in the sense that the results — e.g. vaccines, detection systems — cannot be applied directly to the construction of new biological weapons. However, there are also “gray” areas where defensive interests and offensive interests coincide. In particular, the Department of Defense has announced plans to construct a new high-containment facility at its chemical and biological warfare test site at Dugway Proving Ground, Utah, for the purpose of testing aerosols of lethal pathogens and toxins. For the immediate future, the Department intends to test “conventional” biological warfare agents such as anthrax, but the overall rationale for this facility suggests it anticipates testing genetically engineered pathogens as well.

The biological warfare program proposed for Dugway Proving Ground is unnecessary, provocative, and destabilizing. If pursued, this program will almost certainly stimulate neutralizing measures by adversary nations and a spiraling interaction of research and counter-research, eroding the Biological Weapons Convention to the point where it is no longer effective. Instead of deterrence, the U.S. program will cause the nation and the world to be more threatened by relatively cheap, easily emulated biological arsenals.

In summary, crucial choices concerning the military use of biotechnology will be made in the near future. Much can be done now to strengthen the biological warfare legal regime and ensure that biotechnology is never used for the development of novel weapons.

Pat Mooney, a Canadian member of the RAF International staff:

One of the things that got RAF/NSF involved in biotechnology and genetic engineering was the understanding that the corn leaf blight which hit Southern farmers in 1970 came first from the Philippines and then hopped through Mexico to the United States. It was effective as a disease because there are 160 kinds of corn growing in the fields, but all of them are almost genetically identical and all are vulnerable to the same disease.

The world’s common bowl of food is a very small group of plants — about 30 of them — which give us about 95 percent of everything we eat. So we are all together vulnerable to the same kinds of problems and same kinds of diseases. The gene pool for these crops is important to all of us wherever we live today.

With genetic engineering and biotechnology — the control of genes — the ability to patent genes and control the future of crops boils down to control over the whole food system. Biotechnology has wonderful possibilities. The danger is partly the regulation of the technology and partly the direction the research is going.

It’s a technology which could, on the one hand, reduce the costs of family farm production and increase profits; on the other hand, it could be used to increase overproduction of commodities and wipe out the family farm. It can go either way; it’s for us to decide which way it does go.

It’s a technology which could help us save endangered species, making it possible for us to have greater diversity in plant and animal life, or it could simply give us super cows and super bulls locked together in an eternal embrace, producing millions upon millions of genetically identical offspring. These are our options.

It’s a technology which could increase the nutritional quality of food available to consumers at a fair price or which could simply increase the shelf-life of grocery store commodities. The choice as to which way it’s going to go depends entirely upon us citizens, as voters.

And at this stage, it’s clear we’re not making those decisions. We’re prepared to sit back and let the companies make those decisions for us. And by the nature of the technology itself, those decisions will have far-reaching life-changing consequences.

This magnifies the question of where the ownership of this technology lies. There’s one very important distinction between the Green Revolution which affected us all a few decades back, especially the Third World, and the Gene Revolution which is affecting us all right now. The Green Revolution was, by and large, a public, non-profit enterprise; the Gene Revolution is entirely in the hands of the private sector. There are very few controls by the public sector, very little government involvement in this technology.

The patenting and private monopolization of plant species, the monopolization of higher-order animal species and now even the possibility of the patenting of “human traits” — these developments pose questions for legislators, of course. But they pose much wider questions for the whole society. It’s time, finally, for the religious institutions to get involved. They can no longer stand back from the discussion; they must deeply immerse themselves in the questions of what life really is and who owns it.

Who has the right to make decisions about the genetic make-up, about life itself? Who’s got the right to say that a gene that’s been cultivated by Third World farmers for ten thousand years can be endowed with intellectual property rights and monopolized by private companies when that genetic material moves from the Third World to gene banks in the industrialized nations? The fact is that most of the breeding stock we use for plants and animals is based upon germ plasm from the developing countries.

The problems can be summed up in one particular situation that happened a couple of years ago. In the summer of 1985, Ciba-Geigy, one of the leading pharmaceutical companies also involved in biotechnology and crop chemicals, came to Ethiopia during the famine to sell a hybrid sorghum variety they owned. That sorghum seed came wrapped in three chemicals — two for disease protection and one to protect against Ciba-Geigy’s leading herbicide, Dual. The whole package was there, in fact, to extend the sales of the herbicide rather than to help the Ethiopian farmers. These farmers couldn’t afford the seed in the first place; in the second place, they couldn’t afford hybrid seed that would yield no seed for future plantings; and finally, they couldn’t afford the chemical package that came with it.

Worse than all that is the fact that Ciba-Geigy and most other companies use a strain of sorghum called zera-zera as the basic breeding stock for their hybrids, a strain that comes from Ethiopia in the first place. It is a strain which has been essentially extinct in that country since 1982. So now they’re selling the strain back to the same country which gave it away freely in the first place. And that raises some morality questions for all of us as to who controls life and who has the right to benefit from life.

A few weeks ago, in a Rome meeting of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, it was proposed that the world work together through a commission on genetic resources to save germ plasm and to see to its free exchange among countries. This commission would establish a world gene fund financed by a tax of perhaps one percent on the retail price of seeds, to be paid by the seed companies. This tax would then be paid back, in a sense, to the Third World through the gene fund so that all the countries could save seed together and have mutual control over germ plasm resources. The United States is one of the few countries which opposes this proposal. We have a lot of work to do in that area.

In the end we’re talking about the control of the entire food chain, not just the first link in that chain. And the prayer, “Give us this day our daily bread,” should not be a prayer to a Ciba- Geigy or a Dupont or a Shell Oil.