Would You Let Us Starve To Death: Textile Workers in Search of a New Deal

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 15 No. 2, "Worth Fighting For." Find more from that issue here.

The New Deal brought hope to thousands of textile workers weary of laboring 12 hours a day for less than 25 cents an hour. The National Industrial Recovery Act, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on June 16,1933 (the 99th of his famous First 100 Days), promised a 40-hour work week at no less than $12 pay ($13 in the North) and an end to child labor.

Unfortunately, the driving force behind the Textile Code authorized by the Act came more from the textile industry than from an organized workforce. The United Textile Workers of America represented less than three percent of the nation’s textile workers; it praised the new law’s recognition of collective bargaining and adroitly used Roosevelt’s encouragement of labor organizing to its advantage. But the Cotton Textile Institute, an association of the largest employers, literally wrote the Textile Code’s wage and hour standards in a vain effort to reduce production at smaller mills and thereby drive up the price of textile goods.

The poorly enforced law wound up encouraging the infamous stretch-out system everywhere — the same system of forcing fewer workers to produce more cloth that had spawned a series of rankand- file walkouts in the late 1920s and thereafter. Workers took to heart Roosevelt’s appeals for cooperation with the Blue Eagle recovery plan, and they responded to “Code chiselers” with an outpouring of letters to him and to Hugh S. Johnson, head of the National Recovery Administration. “You ask us over the Radio to write to you if we see where the N.R.A. do not help us Textile workers,” began a typical letter detailing instances of overwork and underpay.

Membership in the United Textile Workers (UTW) also soared — from 15,000 in early 1933 to 270,000 by August 1934 — and when the national union failed to confront the lawbreakers, workers took action themselves. In July 1934, 40 Alabama locals walked off the job. A majority of the 600 new locals voted to join them, and a reluctant UTW leadership finally called a general strike for September 1, 1934 (Labor Day). At the peak of its three-week duration, over 400,000 workers from New England to the Deep South had left their mills, making it the largest strike in the nation’s history.

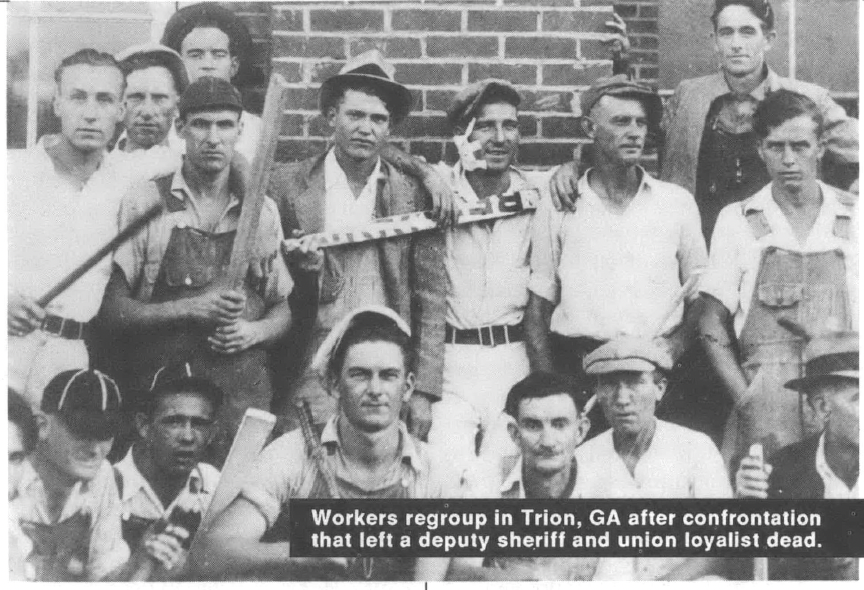

“Flying squadrons” — caravans of itinerant picketers — peacefully closed down dozens of mills until the industry and its allies responded with brute force. The governors of South and North Carolina mobilized the National Guard. On September 15, three days after winning a landslide primary election, Governor Eugene Talmadge ordered Georgia’s Guard to roundup “vagrant” workers and place them in virtual concentration camps. At least 13 Southerners were killed and many more wounded. Martial law reigned from Rhode Island to Pennsylvania to Georgia, and Roosevelt formed a special commission to negotiate a settlement.

Beaten by “force and hunger,” the union accepted the commission’s vague recommendations for Code enforcement and government study of the stretch-out system, and the strike ended. Inside the mills, virtually nothing changed. In some communities, the strikers’ solidarity created the basis for further organizing, but in most parts of the region, the UTW’s false claim of victory left a deep skepticism of labor unions.

Much of the workers’ struggle for a genuine new deal is recorded in a remarkable collection of letters now found in the National Recovery Administration’s papers at the National Archives in Washington. A moving book, with a lengthy chapter drawing on these letters written to government officials, will be published by the University of North Carolina Press this winter. Entitled Like A Family: The Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World, it is the product of several years of research by UNC’s Southern Oral History Program and is authored by Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, James Leloudis, Bob Korstad, Mary Murphy, LuAnn Jones, and Christopher Daly. We thank them and Larry Boyette for bringing these letters to our attention.

The “Research Consortium on the 1934 General Textile Strike” would appreciate obtaining other letters, photographs, interviews and similar materials related to this historic event. Contact Vera Rony, Labor Studies, Room 4310, State University of New York, Stony Brook, NY 11794; phone: (516) 246-6785.

THE LETTERS

7/19/33

Columbia, South Carolina

Mr. President:

Would you let the people in the Pacific Mills starve to death? That’s exactly what is going to happen if something is not done about it. They are being cut off big droves. They say if you aren’t equal to $12.00 per week they will not work you. They cut off the people and stretched out the work so they can do $12.00 worth a week. I had a regular job in the spinning room running 9 sides — that’s not a full set but it’s all that I could run. I haven’t been working in the mill long enough to run 16 sides. They taken my 9 and put them on the other spinners, put me on a cleanup job and I don’t know anything about it. I have got to learn, and they told me they couldn’t pay me a penny for learning.

It’s just several more in my fix too and others depending on us for support. It’s terrible. We can’t live to save our life under such conditions. I don’t mind working — I love to work — but I think the Mill Company should at least consider us as being human.

We hope that you will consider what I have said and do something for the good of the people. Mr. President, they could at least take the stretch-out system off and let us run as many sides as we can and pay us according to the sides we run. When we was working 10 hours a day, I ran 9 sides in the spinning room and worked the whole week, which was 50 hours, and made $4.65 and now I don’t make anything. It was a poor do at that, but I did get by some how.

I’m glad that you have got the hours down and the pay raised, and please do something to put us back on the pay roll. I’m just a girl of 19 years old and have a long time I hope before me to work. Please hold my name and do not publish it.

—Miss Veannah Timmons

8/26/33?

Gastonia, North Carolina

Mr. Hugh S. Johnson

Dear Sir:

I am writing you this letter to let you know just how we poor Negroes are being treated here at Manville Jenckes Co. Loray Mill. There are some who work 8 hours, some 10,11, or 12 hours a day, and all [who work] from 8 to 12 hours make only 20 cents per hour. Our boss man, T.A. Graham tell us the new Code law don’t cover us Negroes for $12 dollars a week— it is just for white peoples. Will you please, Sir, look after this and do something for us poor Negroes?

A white man told me to write you about it. He is a man [who] works in the timekeeping office who said we Negroes were all rated in the main office at 8 hours a day and 30 cents per hour and 12 dollars a week. And when a N.R.A. inspector come, they just show him a fake time sheet and go on. And he said the way you catch them, you send a man here on Friday — that is pay day — and let him go with the pay man and see every Negro paycheck.

Please Sir, Mr. Johnson, do something for me. I work 8 hours. Only make 8 dollars a week. I have 5 in family and I can’t buy food enough to last me from one pay day to another. At the price of food, I can’t have dry bread. Please do something for us or we will starve. Please Sir, come to our aid for we poor Negroes can’t help ourselves. Please put this letter in the newspaper. I am a Negro and work at Manville Jenckes Corp., Loray Mills, Gastonia, N.C.

—Name withheld

2/14/34

Greenville, South Carolina

Dear Mr. Roosevelt,

The American Spinning Co. went on strike Monday, February 11,1934. The weavers walked out and then stopped all others from their work. They are all for the right thing and are only asking for the right things. This mill still has the stretch-out system. Instead of putting more people to work they are laying them off and are working the people to death. This mill has got a minute man that has caused the stretch-out and the supt has got the whole mill speeded up until they are working the people to death and are not making anything. They are not going by your code at all.

This mill is running 9 hours a day instead of 8 hours. Your rule were 8 hours and if you don’t believe it, you send a man here to investigate and he will learn a plenty.... and the hands are doing as much work in 8 hours as they used to do in 12 hours. The supt has got the whole mill tore up and in a mess and are treating the people worse than convicts.

They used to have three stairways to get out of the mill and he has tore some of them away and in case of fire it is dangerous, and have got a fence all around the mill and keep the gates lock. And when you are sick and want out, you have got to walk nearly a mile to hunt the gate man. Got ten gates and one man to watch them all. They could put two more men to work there.

The people ain’t struck for higher wages, but they want a new supt and to get rid of the minute man and to be treated like human beings and not like slaves and they want the stretch-out taken off of them. In the cloth room the superintendent won’t let the hands speak to each other. Mr. Roosevelt, ever one know you have done a great part by the people and we are asking you help. There are men here on starvation that has family and can’t get work any where. May God’s richest blessing rest upon you and that we may all be happier thru the coming future.

Yours truly,

—Miss Dorothy Taylor

Please don’t mention my name. They won’t never work me any more and will make me move.

1/14/35

Hogansville, Georgia

Mr. Eugene Talmadge

Atlanta, Georgia

As I see it Dishonorable Governor:

I wish I could conscientiously say as I once thought as you as Honorable Eugene Talmadge but you have proved to my mind a Tyrant in every sense of the word and an enemy to the poor working people.... Your method and plan when people organize to better their conditions and try to get fair treatment and to protect themselves against the extortionate hoggish Mill Officers who own the controlling interest in these mills, is to send out National Guards and put the workers in prison, herd them up in a pen like a bunch of cattle.

It seems to me that your plans are to herd the men and women that are trying to better their conditions up in a bam or Detention Camp and let someone else who is almost ready to starve take their jobs at starvation wages because they are made to believe they must do this. And you sending out guards tends to create violence and I believe that you know your only motive as I see it is to mislead the workers.

I was not in favor of violence in my life until you sent the guards to Newnan, Georgia and I was arrested and carried to Atlanta, where we were herded in a pen like cows, not because we had committed any violence but because as I see it you wished to break the strike and help the mill owners to keep the workers in slavery and such tactics as you are using will eventually bring about a Revolution. I am not an educated expert but you are using damn poor judgment.

... remember what you said before you were elected Governor, that you were the best friend that labor had ever had and was in favor of organized labor. You said this was why the Big Four Railway Union was supporting you. You said, as long as we, the strikers, committed no violence we had a friend in the Governor’s chair and I believed then that you meant it and I supported you, using all the influence I could among my friends to vote for you for Governor.

I spent my own money and used my own car to help elect you to your office and for my trouble and expense you had my daughter and myself herded into a bam and penned up like cows, not because we had committed any crime or any violence but because you wished to keep us in slavery. My daughter and I helped to close several mills and had no trouble. Not even a lick was passed between the strikers and scabs. We did not go out to make trouble, we went to help the workers close the mills until the owners of the mills decided to give us better working conditions and cut out the Damnable Stretch-out System but you want us to work for just as little as can be paid. Isn’t that true?

I wish you had to work for 50 [cents] a day until you learned how to treat working people.

If you can answer this letter and explain your position, I would be pleased to receive an answer but if you cannot do this, I don’t care to hear from you. My address is, International Street, Hogansville, Georgia.

—J. M. Zimmerman

10/19/34

Greenville, South Carolina

Dear Mr. President:

I don’t know what the textile strike is all about. But I do know all about the life of the cotton mill worker. I have been employed in the mill since I was twelve years old. I was bom and raised in a mill village. My parents were mill employees.

The life of the average textile worker is a Tragic thing. I wish you would come down south to Greenville, and just stand at the gates and watch the Hungry depressed desperate faces of the employees. They are underfed, ragged and unkept. I have heard people say that there was no necessity for cotton mill workers to be dirty and unkept. My friends, let me tell you the work is stretched and heaped on our workers until where they do get off, they fall in the nearest chair, bed or any place at all to rest their aching bones.

I am not speaking as a union sympathizer. I do not belong to any union. I am supposed to be a free white American citizen, but am I? No, I don’t dare call my soul my own. I don’t dare speak my opinion in this strike situation.

I have gone through sleet and snow winter after winter without shoes or half enough clothing to keep me warm. My children are doing the same thing. My own pathetic childhood is being repeated in my own children.... It was the dream of my childhood that I could some day attend school like other children. But my father was a cotton mill worker and the father of a large family and he was never able to let us go to school. So each child was brought up in the mill instead, going to work at ten or twelve years of age.... I want my children to have some kind of chance. I like thousands of others did not strike with the union because we knew we would lose our jobs like thousands of others have done before us....

I am speaking facts from my heart that can be proven to you. I am speaking for the human lives around me.

It is true that every textile worker in the South would walk out of the mill today if they were not afraid of starvation. I don’t believe that God intended people to suffer as we have suffered and shall go on suffering until some terrible things happens to release us from our balls and chains....

I do wish you could don a false mustache and view the situation for yourself. Oh yes, you would have to come unannounced other wise it would be fixed so that the work would be running smoothly. And one would think we were only a pack of ungrateful selfish human beings....

Just a laborer begging for justice for my fellow citizens. For my children and for my invalid husband, for the free? White people around me.

— Name withheld