This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 15 No. 2, "Worth Fighting For." Find more from that issue here.

What can you do when state officials announce plans for a highway through your neighborhood, or when an out-of-state corporation says it wants to put a hazardous waste treatment facility a few miles from your home? Where can you turn for help if real estate developers with close ties to local politicians decide to build a condominium and shopping complex in a sensitive watershed area? How much energy should you devote to door-to-door organizing, or soliciting help from the media, or researching your opposition, or getting involved in electoral politics?

For the past two years, the Institute for Southern Studies has been conducting an investigation of environmental and land-related issues in one state, North Carolina. In a remarkable number of cases, local citizens groups — even those in relatively isolated rural areas—have won significant victories against impressive odds. They have forced state policy makers to change regulations, enact new laws, and enforce existing environmental standards. They have built ad hoc coalitions and enduring organizations, occasionally across race lines, more often across class and cultural divisions within the white community. And they have moved from crisis-oriented, hit-and-miss organizing to sophisticated political lobbying and effective electoral activism.

Many of the key ingredients identified in these successful campaigns are discussed in the following essay, which is adapted from the introduction of a new book being published by the Institute. The book, entitled Environmental Politics: Lessons from the Grassroots, features 10 case studies highlighting the experiences of citizens involved in conservation struggles all across the state. It is available for $7 from the Institute at Box 531, Durham, NC 27702. And as this article by project coordinator Bob Hall illustrates, the location may be North Carolina, but the lessons are useful to people throughout the South and beyond.

North Carolinians view their environment with a special pride. “If this isn't the Southern part of Heaven,” goes a popular saying in Chapel Hill, “then why is the sky Tar Heel blue?” In the western mountains (one-fifth of the state’s counties) and in the eastern coastal plain (one-third of the state), a majority of people depend on an economy directly linked to the quality, productivity, and attractiveness of the environment — to family farming, timbering, and fishing, and increasingly to the tourist industry. In the remaining part of the state — the central piedmont — an economy built around low-wage textile and furniture factories in dozens of mill villages has meant many North Carolinians supplement their income from “public” jobs with gardening, hunting, fishing, and part-time farming. Although the state is the tenth most populous in the nation, nearly one-half of its 6,200,000 people still live in communities of under 2,500 residents; in 1984, only one in five lived in a city with a population of over 40,000.

Demographics and economics conspire with North Carolina’s alluring physical charms to reinforce its citizens’ appreciation of its natural uniqueness and vulnerability. Fully one-half of North Carolina adults say they regularly enjoy outdoor recreational activities. In the same survey, commissioned in 1983 by Friends of the Earth, 70 percent of the respondents say the state’s natural environment was equal to or better than any other in the United States. A poll conducted the next year by the state’s Office of Budget and Management found that 75 percent of North Carolinians rate their environment as “good” or “excellent” and half want the state to take stronger measures to protect it.

Large numbers of transplanted Yankees in the piedmont, mountains, and several coastal counties are working with natives to make control of growth a major issue in local politics. The state ranks in the top five nationally in the growth of in-migrating retirees, people who place a high premium on the natural and built environment. But it is important to recognize that the population’s overall strong feelings on the environment flow less from a romantic love of nature or an intellectual understanding of ecosystems than from the state’s peculiar history and its people’s everyday lifestyles. To a remarkable extent, the political economy and social traditions of North Carolina remain closely tied to the land. The Farm Bureau is one of the most potent lobbies in a General Assembly still dominated by rural legislators. Hunters and fishers make the North Carolina Wildlife Federation, with over 40,000 members, the largest “environmental” organization in the state. And politicians, preachers, editorialists, and songwriters routinely extol the virtues of North Carolina’s countryside, along with a plea for the preservation of traditional rural values.

Strategically, this living legacy means issues related to land use and the environment can be explosive, generating intense public reaction for better or worse. For example, more than 1,700 letters flooded the U.S. Forest Service in the five months following the revelation that its “50 Year Plan” called for increased clear-cutting and reduced hunting on the government forests that cover 42 percent of western North Carolina. And more than 3,000 people turned out for a public hearing in tiny Pembroke to protest the siting of a hazardous waste facility in the Sandhills area.

On the other hand, a majority of North Carolina counties still lack land-use plans or zoning, and proposals for such plans frequently meet vigorous opposition from the same people who oppose toxic dumps but who cherish the outdated belief that “nobody should be able to tell me what I can or can’t do with my land.” Like many Southerners, North Carolinians are protective of their environment — and defensive of their rights to use it in time-honored ways. Jim Hunt, considered a “pro-environment governor” by the Sierra Club and other such groups, was still unwilling to pursue a statewide land-use planning effort begun by his predecessor for fear it would alienate the agricultural community. It was this predecessor, a Republican governor with relatively few ties to the rural establishment, who pushed through the Coastal Area Management Act that has become one of the strongest weapons in the evolution of environmental policy in the state.

Tactically, this rural-oriented political culture means that anyone organizing around an environmental (or any other) issue must take into consideration the best ways to reach, educate, and motivate people. A pig-picking rather than a rally or march may be the best way to get a crowd together to hear speeches. A gospel “sing” can be an effective fundraiser, a place to recruit volunteers for a voter registration drive, and an event that can, with the right choice of choirs/groups, integrate an otherwise segregated “constituency” for an organizing campaign. Outsiders are not so much mistrusted as they are scrutinized for their sincerity, humility, credibility, and genuine helpfulness. The church is still a central place for sharing information and giving leadership on a wide range of issues. And one’s choice of words is often crucial — “conservation” groups are popular, building on a tradition that includes the Soil Conservation Service, but the word “environmental” is less acceptable in a group name or slogan because it conveys images of intellectuals concerned about snail darters and the redwoods rather than people’s everyday lives.

Indeed, the central lesson in all the successful organizing campaigns we studied is the importance of connecting the “environmental” issue to its broader (1) public health, (2) economic, and/or (3) recreational consequences for a specific community or constituency. The battle around peat mining, or a nuclear waste site, or an offshore island development in Onslow County, or a toxic treatment facility in a Durham neighborhood may still be described in the mainstream press as an environmental controversy. But to build mass support for stopping these activities, each campaign had to educate thousands of local citizens about the destructive effects of such projects on their immediate lives. When residents heard the words “environmental damage,” they knew that their livelihood, their traditional lifestyle, and/or their family’s health was in jeopardy.

VALUES AND LEADERSHIP

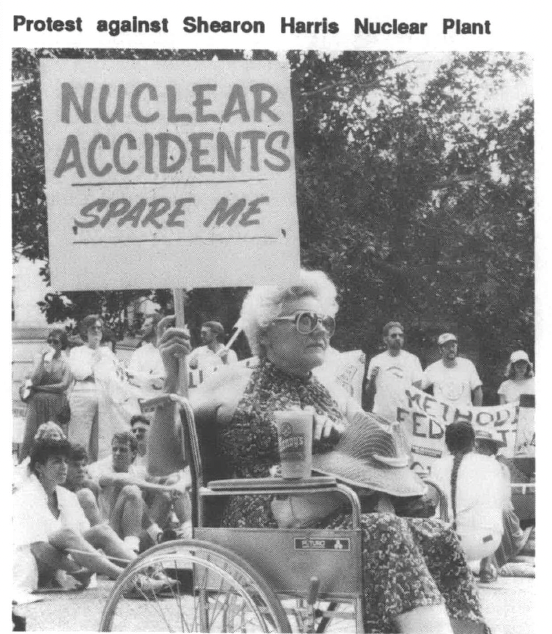

In virtually every situation we studied, the original activists were made to feel hopeless and isolated by the powers-that-be (elected officials, the media, regulatory agencies, etc.) to whom they first took their problems. They were put on the defensive, ignored, or called troublemakers; sometimes they were called liars or “a fringe element” or irrational, or were otherwise personally attacked and had their motives questioned. They were frequently told nothing could be done to change the problem they wanted corrected (stopping an expressway from coming through a Durham neighborhood, blocking the siting of a radioactive waste incinerator in Bladen County) or that everything possible was already being done to ensure that the problem was solved (the development on Permuda Island would not pollute the surrounding shellfish waters, the evacuation plan for the Shearon Harris Nuclear Plant was totally adequate).

Only the right mix of patience and persistence allowed the early “troublemakers” in these struggles to demonstrate that what some considered to be a private grievance was in reality a matter of grave public concern. Ultimately, they impressed the politicians with enough people, the bureaucrats with enough paper, and the media with enough drama to transform themselves from isolated victims into well-connected protectors of the American dream.

This positive posture of protecting the public’s health or the values of our forebears is a key ingredient in each success story we observed. A moral undercurrent in each of these struggles was both sustaining to its inner core of activists as well as compelling to a larger body of supporters and the public at large. It is also a crucial factor in building a positive momentum for those engaged in any struggle; it reinforces their sense of “rightness,” the urgency of their fight and, perhaps most important, a contagious conviction that they will ultimately prevail. People are attracted to a campaign that projects an upbeat attitude about its mission and its ultimate success. They are less inclined to help a group of beleagued naysayers who seem overwhelmed by their own despair.

The peat mining and Permuda Island struggles were especially successful in presenting environmental issues as crusades to protect the subsistence fisherman’s way of life against outside corporate interests. A low-income East Durham neighborhood gained the “moral” high ground and the public’s sympathy for its campaign against the continued operation of a toxic-waste recycling plant by pointing out that the plant would never have been allowed to exist in the wealthy sections of town. They protested their treatment as "second-class citizens” while defining themselves as protectors of the city’s public health. Inspiring individuals to believe that they can make a difference through collective action is critical to building the momentum and gaining the mass support needed to prove that change can in fact happen. Middle-class and upper-income whites are generally confident and indignant, convinced that they can get attention for an injustice done to them; too often, that self- confidence tricks them into thinking they can change anything on their own, without an organization. Alternatively, they may become cynical about the prospect of “fighting city hall,” but that cynicism is often just the flipside of a negative attitude or blissful ignorance about the fruits of engaging in organized struggle. Blacks are generally less tied into the system and more willing to fight for their rights, but they get weary of being asked to follow other people’s initiative without reciprocal support.

Lower-income, working-class whites are often the hardest to get involved. They are more pessimistic about change coming from the bottom up, having witnessed the favoritism and retaliation of the economic and political “bossmen” inside and outside the workplace. They may join the top-down Reagan revolution, but they need lots of support to take risks, especially against local authorities they may know casually. They are more likely to take such risks on environmental or other issues that threaten their family, their income, or their self- respect. To keep involved, they — like everyone else — need (1) positive reinforcement from their peers and, through the media, the larger community; (2) fun events that keep their spirits up and nurture solidarity; and (3) small victories that prove change can occur. Beyond all the talk about models and methods of organizing (including what follows below), the successful campaigns we observed hinged on the positive personalities and values of individuals who project a winning attitude toward small and large challenges and

who inspire others to take on tasks they may not at first believe themselves capable of doing. Gloria McRae of Citizens for a Safer East Durham, Anne Hooper of Carteret Crossroads, Steve Schewel of the People’s Alliance, and Lena Ritter of the Stump Sound Fishermen represent a spectrum of such personalities; it is noteworthy that many of these sustaining, energizing leaders — especially at the local level — are women. While men often get preoccupied with the power dynamics in a controversy and dominate the strategy discussions, women are frequently more in touch with the vision and deeper emotions that pull masses of people into action.

VISIBILITY AND EDUCATION

Making the controversies highly visible and a matter of public debate was another key part of the victories we studied. Issues in the campaigns were popularized and politicized; they demanded attention from people by being injected into as many public arenas as possible. Each arena had to then be persuaded with whatever special language it understood — politicians listen to voter power, the church to moral language and to its members, the courts to legal arguments; the media need drama, action, and authority figures; a group of hunters, blacks, or farmers wants to hear how the issue affects its members.

The mainstream press was used in a variety of ways to (1) publicize the issue and (2) pressure decision makers to address its solution. In a state like North Carolina — where a majority of adults in 63 of 100 counties have not finished high school — television, followed by radio, are the most persuasive forms of media. In general, reporters are overworked, competitive, ignorant of the issues, cautious about covering new or complicated topics, and in need of human drama and conflict that is news. Groups used a variety of methods to overcome these limitations and satisfy the press’s needs. The Stump Sounders gave boat tours for reporters (as well as for politicians and the regulatory agency staff) so they could witness the fragile nature of the environment around Permuda Island — and taste the oysters from the Sound.

By convincing a reporter with the New York Times to write an article about their struggle, the opponents of the Shearon Harris Nuclear Plant gained legitimacy in the eyes of the local media and forced them to cover their actions even more closely. The “hook” for the national media was how the fears over Chernobyl were affecting local reaction to power plants. In the peat-mining controversy, the press couldn’t resist the drama of a multibillion-dollar federal agency and Washington cronies like William Casey going up against a bunch of fishermen with loads of “character” —and the N.C. Coastal Federation played the story for every ounce of attention they could get. The opponents of the two proposed sites for high-level radioactive waste drew attention to the human side of their battle by staging a caravan expedition between the western and eastern sites, with press conferences all along the way.

While all these groups made effective use of the media, they paid even more attention to a public education program that went directly to the constituencies they wanted to mobilize or change, without the biased filter of the media. The fishermen used the two-way radios on their boats. Fact sheets were distributed to stores and churches. Barbeques, oyster roasts, picnics, auctions, and concerts became fundraising events as well as rallies to update and motivate people. Letter-writing campaigns to local newspapers and call-in shows for radio and television got the message out more generally. Two groups used videotape to record personal stories, expert testimony, and events that could not be easily duplicated but which could be rebroadcast to other gatherings.

The “public hearing” became the most important educational tool in the particular campaigns we surveyed. Whether they were called by government officials or by the citizens leading the opposition, these forums provided (1) a focus for organizing mass turnout, (2) a convenient format for the press to cover the issues in the controversy, (3) an almost mandatory platform for politicians, (4) an arena that easily puts the sponsor of environmentally risky business on the defensive, (5) an educational event on neutral turf (school auditorium or city hall) that attracts interested but undecided people, and (6) a chance for the environmental group to develop its outreach, public education, media, speaking, planning, and research skills.

With good organizing, these events gave conservationists an excellent opportunity to (1) put themselves on an equal footing to challenge the company and/or regulators, (2) impress politicians with the mass opposition to the project, (3) demonstrate to die uncommitted who came to the event the contradictions of the proposals, and (4) renew the commitment of the already convinced and allow them to enjoy the power of their collective voices.

POLITICAL PERSUASION

The public hearing was a useful format to master because the focus for citizen protest generally involved political bodies at the local level (city council, county commission) as well as agencies that were vulnerable to the demand for local “fact finding” hearings. Most citizens demonstrated a remarkable capacity to analyze the procedural or legislative powers of each agency and choose a strategy that took advantage of the group’s strengths and the agency’s weaknesses. (They often had friends within the agencies feeding them valuable information for such decisions.) Because these were popular citizen revolts that had mass appeal in local areas, the groups invariably chose to focus major attention on local political leaders who could in turn put pressure on the state or federal agencies. Once the local political leaders got on the bandwagon, it became easier for other politicians, as well as other citizens, to join the campaign.

The East Durham group decided early on that even though permitting plants to handle hazardous chemicals fell within the state’s jurisdiction, their best chance of action lay with the Durham city council. They chose a strategy that focused on the irrational (though technically legal) city zoning which allowed the plant to be in the neighborhood in the first place. And they chose the city council as their target because it was (1) most accessible to their members, (2) most vulnerable to publicity about the neighborhood’s problems, and (3) most easily pressured by other groups the neighborhood could rally to their side. Eventually, a defensive city council was forced to prove its commitment to East Durham by taking the neighborhood’s side in aggressive bargaining with the state over the permitting process, including the choice of location for the state’s public hearing. The council also rezoned the area, limiting the plant’s capacity to the point that it became uneconomical to operate.

In most cases, the environmental activists had ample amounts of sound research to bolster their side of any argument Fact sheets used in door-to-door canvassing, a pivotal community survey and policy report on the expressway’s impact in Durham, and the technical evaluation of GSX’s proposed hazardous waste facility in Scotland County, illustrate how action-oriented research can help in organizing. All the campaigns demonstrated in numerous instances the importance of thoroughly investigating the economic, political, corporate, legal, public health, and environmental sides to an issue as well as the personalities involved.

Understandable, well-documented technical information is obviously another key to success, but many groups fail to recognize that information alone will not win their fight. It rarely even persuades the bureaucratic agencies which supposedly monitor and enforce existing laws based on an evaluation of technical data. In reality, the agencies exist within a “policy-making framework” which is ultimately guided by political actors who respond to public opinion. Often these elected or appointed officials need technical data to support whatever policy decision they make, especially when that decision can be challenged in court by the losing side. But it is difficult to overestimate how flexible they can become in interpreting or reforming existing procedures or laws when they are pressed by a massive and sustained public outcry.

In the controversy over a proposed low-level radioactive waste incinerator, state officials first told residents of Bladen, Cumberland, and Robeson counties that there was little they could do to stop the facility from locating in the area. But after several months of organizing, the plant’s opponents gained so much local support, including from their county and statehouse elected officials, that the state environmental regulators were forced to hold a series of “fact finding” public hearings in the area.

Before the meetings, state officials were still saying that emotional arguments against the incinerator would carry no weight; however, after more than 5,000 people turned out for two hearings, the state’s secretary of human resources admitted he was impressed by the intensity of local opposition. “The laws, the rules, the regulations give no way to consider numbers of people,” he said, “but obviously numbers impress people in public life. They have some effect, but not as much as the information does.”

Several weeks later two agencies denied U.S. Ecology’s requests for the air pollution and radiation permits necessary to open the incinerator. The state used the poor environmental record of the company in other locations as a basis for denying the permits. U.S. Ecology said it would challenge the denials in court, arguing that the state has no set of specific standards for such rulings and that they were “politically motivated.” The company is right about the political motives behind the state’s action, but the bureaucrats were smart enough to build a well-documented basis for their decisions so that they could hold up in court.

The anti-incinerator leaders, who had first investigated and publicized the poor environmental record of U.S. Ecology in other states, had learned the lesson of combining useful technical information with aggressive grassroots organizing.

ORGANIZING

Direct organizing, door-to-door, person-to-person, is another key ingredient in these success stories. There is no substitute for going directly to the people who are affected by an environmental problem and educating/mobilizing them. That was the way new leaders in the peat mining and East Durham toxics campaign were identified — from direct, one-on-one contact, canvassing the area or constituency most affected by the problem, using a fact-sheet and spending a lot of time with the individuals who later became the backbones of these movements.

Very often environmental groups tend to identify a problem, research it thoroughly, attempt to publicize it through the media, and seek remedies through the appropriate governmental channels. They miss the most important ingredient — the human beings who can articulate how they are directly abused in a way that arouses others to sympathy and/or action. These primary or potential “victims” become the center of a media, public education, legal, and lobbying strategy because they can best explain in human terms how a complicated environmental issue connects to the welfare of real people. Thus the fishermen and their families, rather than the environmental experts, invariably took center stage in any strategy designed by the peat-mining opponents.

At the other end of the state, long-time residents of the coves in Haywood and surrounding counties became the backbone of the movement against siting a high-level radioactive waste facility in the mountains. The Blue Ridge Environmental Defense Fund and Western N.C. Alliance had begun working on the issue before a specific site was selected and before opposition mushroomed to include even real estate developers worried about the proposed facility’s impact on tourism and the second-home market. But without the broad support of average citizens, environmentalists — like realtors — can be isolated as “special interest groups” not in touch with the welfare of the general population. Spending the time to cultivate relations with native mountaineers, not just the retirees and newcomers, paid off for conservationists.

In each successful case studied, more than one “constituency” was intimately involved in the campaign; in fact, the constituencies were often quite diverse, and they ultimately gained strength through their ability to mobilize different parts of the larger community. The East Durham residents or Stump Sound oystermen may have been most visible in their respective struggles, but they understood the importance of maintaining working relations throughout their campaigns with other organizers and leaders working with other constituencies. Traditional environmental organizations, to the extent they were involved in the mass efforts at all, also understood that they were only part of a movement working for change.

In the East Durham case, a formal coalition emerged to tackle passage of a “Right-to-Know” bill in the city, using the explosion at the East Durham toxic facility as an example of its need. The components of this coalition (ranging from the Sierra Club to People’s Alliance to the local AFL-CIO) were also important in getting the existing facility closed down. They could turn out people for public hearings and use their clout with the city council in favor of the East Durham neighborhood. In a similar way, other groups in Onslow County and along the coast helped the Stump Sounders with lobbying support, press contacts, access to needed resources and information, connections with helpful state agency personnel, and a broader forum for public education.

In the fight over the U.S. Forest Service’s 50 Year Plan, an unprecedented alliance between local and statewide sportsmen clubs, national environmental organizations, and a network of activists concerned about different land-use issues (the Western N.C. Alliance) totally surprised the government with the amount of grassroots opposition and technical expertise they could throw against the Plan. When die nuclear waste site was announced for the same area of North Carolina, an even larger coalition proved too much for the federal government. With nearly universal opposition to the site in the mountains and another near Raleigh, the Republicans stood to lose two very close 1986 Congressional races (11th and 4th Districts) and the Broyhill-Sanford race for John East’s seat in the U.S. Senate. Similar political problems in other states apparently led Reagan’s Energy Department to come up with a technical excuse for suspension of their search for a waste site in the eastern U.S. (The Republicans still lost the Senate and two House seats in North Carolina.)

In all these fights, environmentalists were greatly strengthened by the involvement of other constituencies who could expand the issue beyond ecology to include jobs, the quality of life, and public health. These other groups also added the financial and people power necessary to go up against a well-endowed corporation or intransigent government agency. The converse of this is also true: When traditional environmentalists tried to confront Texasgulf over its pollution of the Pamlico River, the giant phosphate mining company ignored them at first; when fishermen began speaking out, Texasgulf defended itself aggressively and mobilized support from county officials, the local media, and its own workers who uniformly praised the jobs and tax revenues it brought to the economically depressed area. The broad base the company enjoys in Beaufort County means its local opponents will need a sharp focus for their reform demands and will likely need allies outside the region to exert pressure on state and federal regulators who are lax in their enforcement of existing regulations governing Texasgulf’s operation.

The successful stories in North Carolina demonstrated a variety of models for how public interest researchers, foundations, national resource groups and professional organizers can help local issue-oriented or political campaigns. In most cases, the key to success involved (1) strong local leadership that had its own base in the community or constituency and a sense of what tactics, language, goals — if not overall strategy — would best suit the people they worked with; (2) clarity on the part of outside groups as to what they could reasonably provide and what their own motives for joining in the fight really were; and (3) enough time and personal trust for the various actors to work out their respective roles, to get and give appropriate recognition, and to deal with each other as peers.

The point here is not that outside groups need to stand back and “let the people decide” in a vacuum. Rather they must listen intently to learn the peculiar dynamics of the local situation, and then forthrightly throw in their two cents, based on their experience. The process is much closer to a dialogue among equals than someone manipulating things from behind the scenes or passively waiting to be asked for advice on a specific detail. Todd Miller of the N.C. Coastal Federation, Lindsay Jones of the Western N.C. Alliance, Kenneth Johnson of the Rural Advancement Fund, and Len Stanley, formerly of the N.C. Occupational Safety and Health Project (NCOSH), all have very different personalities and organizing styles. But their successes in the campaigns we observed had a lot to do with their capacity to spend considerable time listening to local citizens, connecting that information with what they knew about regulatory agencies or organizing techniques, and offering a response or question that could carry forward the strategizing/ organizing process.

Lawyers, researchers, foundations, and Washington-based national groups can, and sometimes do, follow a similar pattern. The organizers mentioned above demonstrated how to be sensitive to local people without being patronizing. They acted as facilitators not in the mechanical sense of “training” others in the technology of organizing; rather, they became deeply immersed in the substance of the issue and the people affected, and they consciously sought to involve them in activities that drew on their individual or collective interests, insights, talents, and resources to carry the campaign forward.

Despite all our attention to human capacities, accidents can sometimes also play a key role. Several of the campaigns we studied were immeasurably boosted by a crisis or explosive incident that became for the public a dramatic symbol of what the controversy was all about The biggest was the Chernobyl meltdown in the Soviet Union which coincided perfectly with a renewed effort to keep the Shearon Harris Nuclear Plant from starting up; the plant received its final NRC staff recommendation for licensing and a shipment of fuel in the days just before and just after Chernobyl. A coalition that already had its fact sheets and basic strategy designed before the accident capitalized on the public fear from Chernobyl to launch a surprisingly successful multi-county campaign that forced the commissioners in one county to pull out of the official evacuation plan (the commissioners later reversed their vote), and caused a six-month delay in the opening of the Shearon Harris plant.

In another case, just before a major public hearing on the peat-mining controversy, heavy rains caused a rush of freshwater intrusion into the shellfish waters and forced officials to impose North Carolina’s first statewide ban on shellfishing. This temporary closing dramatically illustrated the impact on the fishing industry of the increased runoff that would result from the peat miner’s ditches. And with the fishing waters closed, more local people could attend the hearing.

The explosion at the Armageddon toxic waste recycling plant in East Durham riveted the attention of a neighborhood and the city on the hazards under their noses. In various ways, that explosion became the organizing symbol for the “Right-to-Know” campaign led by NCOSH, for the neighborhood battle against die plant’s continuing operation, and for the next city election.

In all the cases, as well as in the “not in my backyard” anti-toxic-dump fights, mass fear became an important ingredient in the success of negative campaigns which relied on mass pressure

to stop something from happening. In some cases, a positive symbol or incident can also sustain a major campaign. The Durham-based Congresssional campaign of Mickey Michaux gained notoriety, attracted dozens of conservation-minded volunteers, and took on the spirit of a movement because it featured a concerted biracial effort to put the first black North Carolinian in Congress since 1901. However, racially motivated fear among large numbers of whites outweighed Michaux’s positive campaign.

RACIAL DIVISIONS AND UNITY

The Durham experiences provided fruitful lessons for whites and black working together in political campaigns and neighborhood issues. In reality, the entire state is far more segregated than most whites and many blacks care to admit; personal or political relationships across race lines are quite exceptional. Racist comments and jokes are on the increase, and interracial collaboration is suspect among many blacks as well as whites. Even in Durham, the working alliance between the Durham Committee for the Affairs of Black People and the two white progressive political organizations is fragile.

Race plays a larger factor in environmental politics than many people suspect. Poor and minority communities are disproportionately selected for everything from landfills to hazardous and radioactive waste sites. On the other hand, many leaders in these communities are attracted by developments that promise jobs and money for the area, and they can seem uncaring about the environmental consequences of such enterprises. Sophisticated developers are smart enough to line up support for their projects from established black, brown, or Indian leaders, while casting environmentalists as selfish and uninterested in people of color. White conservationists, concerned primarily about recreational and quality-of-life issues, play right into this racial split by ignoring the call for help from minority communities faced with environmental problems (from energy bills to poor water and sewage systems to toxic dumps) and, on the other hand, by ignoring the deeper

economic and political disadvantages people of color keep struggling to overcome. When established black leaders in Durham County sided with the developers of the 5,100-acre Treybum mini-city, conservationists lost an indispensable ally. With little support from rural residents in the project area, their pleas for protecting the fragile watershed became an isolated cry, without political foundation. All across the South, such defeats could be reversed with stronger coalitions across race lines.

To make a multi-racial alliance work takes (1) constant energy, negotiation, education, and commitment; (2) a self- consciousness among the leaders of their limitations without, and strengths with, a coalition; (3) consistent delivery on promises made and holding up one’s end of the bargain; (4) a recognition of differences, including sometimes conflicting agendas; (5) a recognition of the power of racism in the history and contemporary life of the community and beyond; (6) education of the membership about the need for biracial partnership; and (7) lots of practical steps that aim to solidify personal and political relationships.

The East Durham neighborhood succeeded in involving both black and white members of its working-class community. The leadership that emerged from the door-knocking and early meetings consciously chose a biracial group of officers. While the president was black, the meetings were consistently held in a white church to keep whites comfortable about their “place” or “ownership” within the organization. (The church actually experienced a revival of membership because of its renewed identification with the community.) Blacks and whites made sure both races were represented when the group spoke at large public meetings. But they also recognized the racial divisions within Durham and assigned themselves by race to educate, lobby and convert leading politicians, political groups, civic clubs, etc. to their side. Under the pressure and daily experience of trying to save their neighborhood, awkwardness and prejudice gave way to humor and comradeship.

The key to breaking down racism seems to be to get whites involved in concrete working relationships with many (not one or two) blacks, and to recognize racism not so much as a moral issue but as the product of historical forces that have practical consequences for today. It works to limit the lives of blacks and, to a lesser extent, whites — including the possibilities that could be achieved by building on common economic and political interests. Racism is so entrenched, however, that is it unrealistic to expect too much change from one campaign where blacks and whites collaborate. Whites still make so many assumptions about their prerogatives of leadership

and about the correctness of their priorities that it takes a concerted effort to deprogram them. The fruits of years of anti-racism work by Robeson County’s Clergy & Laity Concerned emerged in its capacity to mount a mass-based interracial effort against the hazardous waste facilities cited for the Sandhills area. In contrast, the group nearby in Scotland County remained largely white, middle class, and preoccupied with legal and legislative remedies rather than grassroots organizing.

Getting whites to vote for black political candidates who are right on the issues is an important next step in reinforcing their anti-racist behavior and consciousness. The political process seems like remote terrain to the average citizen as well as to many dedicated environmentalists. But, inevitably, the activists in issue campaigns confront the fact that they can’t win without getting better public officials elected, and they can’t get them elected unless they understand how to use their strengths at the grassroots to register new voters, target key races and precincts, and turnout supporters on election day.

Non-partisan voter registration (VR) and get-out-the-vote (GOTV) efforts, regardless of race, are most successful where there are strong issues that motivate people. Of course the momentum of such work is either strengthened or undercut by the positions and leadership of the candidates in the

election, but to some extent issue-oriented VR/GOTV work built around an issue rather than a candidate can succeed. It is even more successful where an organization or education program has a continued presence and can (1) analyze precinct results over several years for improved targeting, etc.; (2) recruit an ongoing base of volunteers; (3) develop a communications program to educate targeted voters about the role of elected officials in their lives, including their role on key issues identified as of major concern to the targeted group; (4) refine a work plan, timetable, and logistical system adapted to the peculiar demography, institutions, leadership, and culture of the area; and (5) develop stronger relations with a broader number of leaders in the community who can be supportive of the VR/GOTV work.

These ingredients for success apply to efforts targeting whites (such as the League of Conservation Voters’ work) or those aimed at blacks. Many blacks and whites we interviewed said it doesn’t work for whites to try to register blacks, and that the real place for whites is in the white community. With great difficulty at first, the SANE group in Charlotte proved that white volunteers can register and get blacks to vote in targeted precincts. But their success pointed out the need to carefully coordinate strategies with existing voter leagues, as well as the continuing frustrations and disagreements that result from whites working in black areas. In larger areas, there may be several groups that traditionally work on registration and turnout in the black community. So the involvement of white-majority coalitions, like NCEC (North Carolinians for Effective Citizenship), or white volunteers from groups such as SANE can be quite complicated and confusing.

As in the cases where several different groups are involved in an organizing project, it frequently helps if the recognized leaders of the overall campaign set the tone and parameters for the participation of different groups. In political campaigns, this means that the candidate and his/her campaign manager can exert considerable influence in setting the stage for outside or new actors to participate in voter registration or voter turnout efforts. In both the Mickey Michaux race, where the League of Conservation Voters took an active role, and in the mayoral election of Harvey Gantt in Charlotte, where NCEC cut its teeth alongside several white-led neighborhood groups, it was crucial that the candidates themselves made the involvement of diverse groups a positive step in the higher goal of electing the “first” black to a major office. In a way, they preempted the role of the established black voter leagues to place their election and their evaluation of registration/tumout needs above the control of these groups.

VOTER CONTACT TECHNIQUES

Phone banks, canvassing, and targeting of precincts are not only a key part of black political empowerment; they are essential ingredients for environmentalists to use in identifying and mobilizing sympathetic white voters. In Durham, white progressives successfully sued for the computer tape of the elections board, allowing them to sort names of registered voters not only by precinct or race, but by age, date the person registered, or date they last voted. In one race, the People’s Alliance of Durham targeted areas that had a large number of newly registered whites (probably in-migrants) to canvas for progressive-minded voters who might be unfamiliar with local political issues. In another, they produced lists of those whites who registered as Democrats in 1984 — when it took a higher measure of liberal commitment to identify with the party of Walter Mondale — and used that list in canvassing for the 1985 mayor’s election.

Here’s what they did in another case involving a liberal white woman against a conservative white man in a 1986 primary race that was expected to have a low turnout. They generated a print-out, by precinct and address, of households with women between 18 and 60 who had voted in the 1985 municipal election, another low-turnout race. These Democrats were considered habitual voters and potential supporters of a woman candidate. (Women over 60 were targeted for special mailings.) The print-out had each woman’s name in bold print and the names of the other registered Democrats in the household listed under hers. One set of volunteers looked up the phone numbers using a city directory; another set made calls from multiple-phone offices, where they could compare notes about what approaches worked best and generally get support for a tedious, sometimes difficult task. The candidate was introduced along with her key issues, and the voter was asked if she (or he, if a registered male voter answered the phone) thought the candidate seemed like someone worthy of support. The response was ranked from 1-5, depending on the strength of the voter’s opinion for or against the candidate, and in the final two days of the campaign many of those with a 1 (strongly for) or 2 were called again to make sure they went to the polls or had a ride if they needed one. The candidate, Sharon Thompson, beat her opponent by 55 percent to 45 percent.

FROM ISSUES TO POLITICS

To succeed, this kind of precinct-level organizing makes extensive use of many volunteers working a few hours a week over a short period of time. In many ways, such partisan political activity is a natural place for the energies of people who have become involved in crisis-prone organizing around back-yard conservation issues. Most of the participants in these community battles do not consider themselves activists. Their lives are filled with family, work, recreation, volunteer work with a club, the 4-H, or church. Electoral politics is not a priority. But if they see that a few hours of their help for a specific candidate will make a difference on issues directly affecting them, and if they are directly asked to help, many of them will make the transition from participants in an issue fight to periodic volunteers in electoral politics.

In many cases, the leaders in the fights we surveyed became very active in politics as a result of witnessing the power elected officials have over the issues affecting their lives. Gloria McRae became active in the East Durham Democratic precinct and eventually its chairman. Lena Ritter coordinated several events in the Stump Sound area to promote the candidacy of two county commissioners (who won) and a state senator (who lost by 700 votes). In May 1986, Jacquelyn Scarboro, a leader in the effort to get Chatham County’s commissioners to withdraw from the nuclear power plant’s evacuation plan, invited U.S. Senate candidate Terry Sanford to a political rally in the county, prompting him to make increased local control over the siting and safety of nuclear power plants an issue in his campaign. The fishermen and environmentalists fighting the peat-mining plant represent other examples of how issue-oriented controversies have led people to become involved in county, state and national politics.

Our study of environmental controversies shows that most people (1) are motivated by local problems, and (2) do not readily transfer their activism from one issue to another, nor from issues to electoral politics generally. However, they do make the connection between their special issue and the fact that elected politicians have control over its fate. Hence there is great potential for linking environmental activists to specific electoral campaigns and then to broader political work. But the issue-oriented coalitions are frequently not able to help make this transition. As ad hoc efforts, they dissipate without conscious work to build on the collective experiences and range of talents of the people involved.

It takes sustained organizations — following most of the points listed above for effective non-partisan groups — to recruit a steady stream of members and/or volunteers into political activity. Political parties attract a limited number of people with different personalities and experiences from those of people motivated by specific issues and grievances, the life blood of groups like the National Abortion Rights Action League, NAACP, People’s Alliance, and the Onslow County Conservation Group.

Carteret Crossroads, a nonpartisan conservation group in coastal Carteret County, represents an example of the minimal level of organization required to keep a network of members and volunteers informed of issues and local politics. The group cut its teeth several years ago in a campaign to stop an oil refinery from being located on an island next to the state port at Morehead City. With each new plan for developing the island (coal port, liquified natural gas facility, ammonium hydroxide storage tanks), the group had to remobilize its supporters and mount enough public pressure to change votes approving the projects by both Democratic- and Republican-majority county commissions.

In the course of these battles, Carteret Crossroads built up a membership, credibility in the larger community, press contacts, and political sophistication. Although it now rarely calls general membership meetings (outside the context of a specific issue fight), it has an active steering committee, a few task forces, and a newsletter that keeps a large list of supporters and members informed of land-use and conservation issues. It issues periodic “alerts” or special bulletins, such as the one urging members to write letters and attend a public hearing in the area on the regulations of storm water runoff. Its leadership is also consciously reaching out to other constituencies in the county, such as the agricultural community, and is moving beyond crisis-response organizing to tackle larger policies, such as county guidelines for the protection of groundwater.

Like many of the other groups we observed, Carteret Crossroads has succeeded in (1) politicizing conservation and development issues through specific public controversies and ongoing public education, (2) cultivating a core of sophisticated leaders whose views are sought by the media and elected officials, and (3) creating mechanisms to keep a network of supporters and members informed on issues and ready for action. While the group is nonpartisan, it has learned how to use the political arena to win on specific issues. And its members and leaders take an active role as individuals in political campaigns, drawing on the network of contacts and on expertise gained through the organization.

New groups like Carteret Crossroads are cropping up all the time. Nearly all remain fragile entities, dependent on shaky finances and strong personalities. But they offer some of the best promise for involving otherwise politically inactive white North Carolinians in a process that increases their commitment to social change, organizational skills, and exposure to working with diverse groups. From these many struggles and groups comes the foundation for greater change in local power structures and in the state as a whole.

Tags

Bob Hall

Bob Hall is the founding editor of Southern Exposure, a longtime editor of the magazine, and the former executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies.