This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 5/6, "Everybody's Business." Find more from that issue here.

One hundred years of "New South " development policies in South Carolina have made industrialists the "fourth branch" of government, especially in the upland counties that now straddle Interstate 85. As a consequence, workers remain unorganized, uninformed, and underpaid. The Palmetto State ranks 50th in per capita union membership, 50th in voter participation, and 48th in per capita income.

Since 1980, the Workers' Rights Project, more commonly known as WRP, Inc., has used a strategy of public education, worker mobilization, and political action to create a climate for employment reform. Begun as a project of Southerners for Economic Justice, it has evolved into an independent membership organization of workers led by a member-elected board of directors, with one full-time staff member and a lawyer on retainer. Its efforts, based in a small Greenville office, are financed by foundations, church funds, and local fundraising (20 percent), including members' dues, raffles, benefit concerts, and other high-profile events.

Over the past few years, WRP has demonstrated that educating the so-called beneficiaries of development policy — the work force — can reshape the ways that local government deals with industry. To get a flavor for what WRP is up against, remember that Greenville's elite has turned away more than one industry that paid too well or seemed too soft on unions (see Southern Exposure, Spring 1979). WRP's primary emphasis is getting information about employee rights to workers through leafletting, public hearings and presentations, "job rights clinics," a call-in service, and publications such as the "Basic Guide to Workers' Rights."

Surprisingly, several thousand workers have participated in WRP programs in this union-phobic region. In several cases, WRP members have even used concerted action techniques protected by the National Labor Relations Act to raise group concerns and change management policies.

Having an organization "in-place" at a time of crisis proved crucial to WRP's first major public policy victory. In July 1984, the organization was approached by 50 workers who had been fired by a vitamin manufacturer which, it turned out, was simultaneously seeking an $8.3 million industrial revenue bond from the city of Greenville. The company had replaced the workers with temporary help who were paid lower wages and denied traditional benefits.

As a means of pressuring the company to give rehire rights to the former employees, WRP and the workers waged a highly publicized fight against the city council's approval of the bonds. The workers were never rehired, nor was the bond issue stopped, but public outcry resulted in the subsequent adoption of progressive development guidelines. Companies seeking industrial revenue bonds must now reveal in the application process whether any layoffs or wage reduction efforts are planned, and they must agree to furnish reports every six months so that employment levels can be monitored.

LOCAL EFFORTS to improve the labor climate for workers inevitably lead to the statehouse. State law affecting industrial recruitment, "at-will" firing (employers in at-will states can fire workers on a whim, for good reasons, bad reasons, or no reasons at all), or use of polygraphs (lie detectors) are a few of the issues tackled by WRP's membership in the past five years. In 1985, WRP initiated an ambitious four-year "Job Rights Campaign" to educate workers about their existing rights, lay the basis for a statewide organization, and generate support for a major offensive to win new protections from the state legislature.

As a first step, WRP Director Charles Taylor announced a series of job rights workshops in key cities. The workshops, conducted by WRP attorney Stephen Henry, provided an overview of employee rights in South Carolina, so that workers could learn what rights they possess and how to get them enforced. The two-and-a-half hour sessions covered topics ranging from age discrimination to polygraph testing. In order to attract working-class participants, they were held at night and cost only five dollars. By the end of 1986, the workshop series had been enthusiastically received by about 50 workers in each of eight cities.

Four hundred workers, plus contacts from people in dozens of towns across the state who have requested various kinds of aid from WRP, is enough of a base to move ahead. As a focus for its legislative campaign, WRP chose the widespread practice of employer's firing workers who file for workers' compensation. "Retaliatory firing" had emerged as a central complaint among workers from industrial, service, retail, and government jobs. Although an estimated 5,000 South Carolinians are fired each year for filing workers' compensation claims, legislation to restrict retaliatory firings has been consistently shelved.

My Turn: Closer to Home

I'm a disabled machinist. I worked at General Bearing with a chemical called Rust Ban 392. It cooked the lower part of my left lung. No respirator, no mask, nothing of no kind. The company doctor recommended me to see a lung specialist, which I did. He wrote back and forth, to the company, trying to get them to take me out of the chemical, which they did not do.

It went on for 18 or 19 months. Then it got to the place that it was beginning to take my strength away from me. I filed for workers' compensation. When I did this, the company terminated me.

The companies tell you one thing, but they do another. As long as you can do their work, you're doing fine. But when you start complaining they call you a troublemaker, because they don't want to hear what you've got to say.

— Mattie Brown, North Carolina

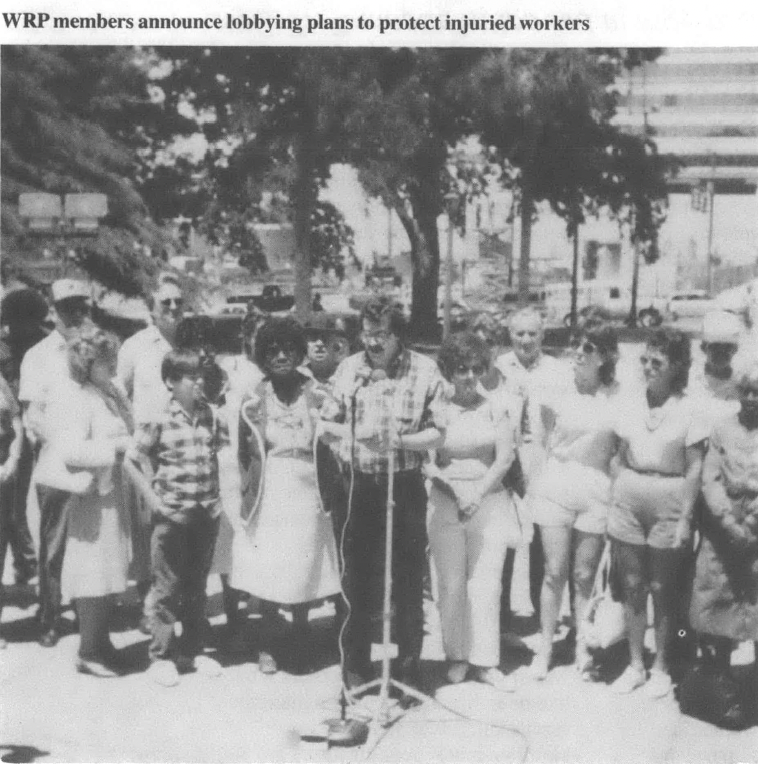

In late 1985, progressive lawmakers on a legislative committee studying workers' compensation invited WRP to help "get the public involved in the workers' comp problem." Amendments to strengthen a pending reform bill were drafted, and the committee held a series of highly visible hearings in Greenville, Charleston, Florence and Columbia. WRP helped identify victims to testify and turn out a crowd for the hearings.

Over 600 workers attended the hearings, and the media focused exclusively on the retaliation issue thanks to testimony of the victims. Some testified that in a "production-crazy" environment, injuries often result from running machines too fast. Others talked frankly of slipping into financial ruin after being injured at work. "You would not believe the nightmare we've been through," one victim said. "We are dead broke. My car has been repossessed and I'm behind on the rent. It's hard enough to deal with the fact that I'm 30 years old and may never work again. I'm asking you — no, I'm going to beg you — just pass a law that keeps employers from firing workers disabled on the job."

The captains of industry had targeted this bill for defeat from the beginning. South Carolina Chamber of Commerce vice president Lowell Reese described the effort as "labor unions and lawyer activists trying to create a 'welfare bonanza.'" During the hearings industrialists brought out the standard line that an antiretaliatory law would hurt industrial recruiting. WRP's Charles Taylor countered: "If a company demands the right to fire injured workers as a condition for moving into South Carolina, why in the world are we recruiting them?"

Publicity about the hearings got the anti-retaliation bill moving, and WRP kept the heat on through a letter and phone call campaign and a group visit to the statehouse at a crucial point. A new law that prohibits the retaliatory discharge or demotion of workers' compensation claimants finally passed. It is stronger than a similar law in North Carolina which only protects partially disabled workers who could fully recover and resume their original jobs. The reform measure became law in May 1986, an event that is incredible when one considers the pro-business economic climate in South Carolina.

GETTING A LAW on the books is no panacea; how well the law gets enforced is the measure of its success, and in this case it's too early to tell. Meanwhile, the opposition in the South Carolina legislature is not admitting defeat. At this writing in November 1986, some of the progressive legislators supporting the bill are under attack for "conflict of interest," because as attorneys they represent injured workers in compensation cases. WRP has jumped into the fray by researching and exposing the corporate ties of the opposition legislators; now it is mobilizing members to write letters on behalf of those under attack.

The inherent weakness in a litigation strategy, as anyone who understands workplace politics knows, is that employers can concoct whatever reason they need to dismiss an unwanted employee. In South Carolina, the burden for proving that a firing is related to worker compensation remains on the employee. But injured workers and their attorneys for the first time now have the means to get into court when an injured worker is fired.

More important than these preliminary gains is WRP's success at getting employees mobilized. The message: political education and action can produce greater citizen/worker power. In the anti-retaliation effort, many workers attended and testified at public hearings for the first time, wrote and called lawmakers for the first time, and observed a legislative session for the first time. For the long haul, that participation is itself more crucial than passage of the bill.

The workshops and issue campaign have also had the effect of developing new working relationships, and hence alliances, with community groups and statewide groups like the NAACP, AFL-CIO, and the Trial Lawyers Association. The success of the legislative hearings in Florence and Charleston especially demonstrated the value of coalition: blacks and whites participated in equal numbers and thereby contradicted the self-serving perception of local officials that the two communities had different agendas.

Encouraged by its legislative success and the participation at its ongoing series of job rights workshops, WRP is building the framework for a statewide chapter system with an elected statewide board of directors, all to be in place in 1988. It looks like South Carolina will be producing a whole new crop of economic justice experts.

Tags

Arlene Sanders

Arlene Sanders is a freelance writer. WRP's "Job Rights Guide" may be ordered for $2 from WRP, 1 Chick Springs Road, Suite 110-D, Greenville, South Carolina 29609. (1986)