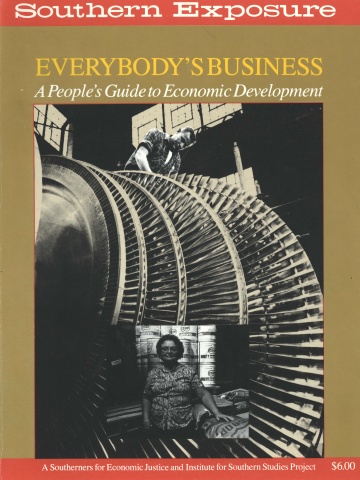

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 5/6, "Everybody's Business." Find more from that issue here.

Economic development is necessary because certain people or places are left out by the natural flow of the market driven economy. Economic development in a developed country like the U.S. rechannels parts of the mainstream economy to benefit these people and places. It is not the same as service delivery, which tries to tide people over until the big stream changes. Nor is it the same as those wholly political efforts to change the economic system. It is an immediate, incremental redistribution of economic opportunity and benefits. Significant redistribution of economic opportunity is really a task for government. Government sets the rules in the first place which determine whom the economy benefits and whom it does not. Governments determine what income and wealth are taxed, write regulations that assign infrastructure, health and environmental costs, and establish enforcement procedures. These policies are contested and negotiated among corporations, workers, environmentalists, consumers, local government officials, and citizen activists. The government policies that emerge from these negotiations shape the distribution of resources and opportunities.

Development, as redistribution, has rarely been an explicit policy issue. In fact, the amelioration of poverty has never been a primary concern. Rather, the national commitment to improve conditions in urban ghettos and places like Appalachia, Indian reservations, the rural South, and the Southwest has been temporary and shallow. Therefore, development organizations have had to develop strategies which can work outside government.

For the past ten years, the Mountain Association for Community Economic Development (MACED) has been trying to "do development" in Central Appalachia. In 1976, a group of community development corporations founded MACED to work with cooperatives and small businesses, giving technical assistance, making investments, basically trying to help small, locally controlled enterprises survive and, hopefully, expand. For several years, our development strategy was straight business assistance.

But small nonprofit development organizations with limited resources and authority need to look for opportunities to achieve some kind of scale in their day-to-day work. We realized that our technical assistance and loans, however welcomed by the immediate beneficiary, were not achieving much in the way of scale. We looked for ways to have greater impact. What we came up with, and are still experimenting with, is a development strategy based on "sectoral interventions."

We try to influence the way an important, existing sector or institution works, steering it toward serving the local economy better and benefiting people at the low end of the scale. We try to bring a public-minded perspective — a development orientation — to the sector, whether it is coal, or timber, banking, even water system management. In some cases, this involves "being a business," while in others it involves conducting research and speaking out on policy issues. In every case, we see what we do as experimental, responding to opportunities as they arise and to energetic people wherever they are.

Sawmills and loggers are important employers of poor people in the most rural areas. Any increase in hardwood sales from the area translates directly into additional days worked by underemployed people who are piecing together a livelihood when steady jobs are scarce.

Therefore, several years ago we established a specialized lumber component of our general small business investing activity, and hired a hardwood lumber specialist. At first we tried to promote secondary manufacturing in the industry, but potential entrepreneurs in our lumber industry had little relevant experience in these higher value added ventures. People in our area do know sawmills, and we received numerous proposals to invest in sawmills.

We made loans to several individual mills, but we realized these mills could not create a significant number of jobs. However, all small mills faced similar problems in gaining access to markets and using available information to make management decisions. If we could improve their market access for the higher grades of lumber, many mills could expand under their own steam.

The mills had no interest in forming a cooperative, so we established a subsidiary to buy, agglomerate, process, and resell the lumber of small eastern Kentucky mills. Since then, the company has been developing markets for loggers, promoting a variety of joint ventures, and making financial analysis software available to the larger mills. Recently we convinced a broker to move from Alabama to east Kentucky, where he is setting up a concentration yard. Through MACED he has access to raw material supplied by local mills and loggers. The mills and loggers benefit from new, larger, and more reliable markets. In another case, we act as an intermediary, helping small operators gain access to quality timber on federal land.

Our initial interest in banking was stimulated by our interest in housing. An analysis of mortgage lending in eastern Kentucky in 1980 showed that the 10-year, 30 percent down demand note was one of the most serious obstacles to affordable housing. We considered trying to start a savings and loan association or mortgage banking firm, but the potential mileage gained through an active consortium of these bankers looked much greater. Several leading bankers recognized the value of a consortium effort to improve lending practices and build a new banking climate in the region. We found other lenders were receptive to the idea, and support snowballed.

We hired a banking expert who drove all over the mountains and helped organize 94 bankers into a consortium. This consortium then became a link for the bankers to secondary markets. We held seminars with Freddie Mac not only to familiarize the bankers with Freddie Mac, but also to change Freddie Mac provisions that worked against rural bankers.

The consortium bankers who used to make housing loans that looked like demand notes now write regular, long-term, low down-payment mortgages. The consortium has issued two mortgage revenue bonds which brought over $46 million into the area in the form of below-market-rate mortgages, and these eastern Kentucky banks became a greater financial force within the state. Now we are talking with some banking leaders about ways to use innovative commercial lending to encourage potential suppliers to Kentucky's new Toyota plant to locate in the mountains.

The coal industry is another important sector in the region. In many areas, coal or coal-related employment is the main source of earned income. In recent years we have begun to look at the coal industry and its impact on communities in the mountains. We are trying to change the debate about coal policy, introducing the notion of "development" into discussions. We are trying to build up the public expectation that coal can and should do more for local economies, both by reinvesting in them and by encouraging stability.

Also, because growing unemployment in the coal industry is a serious structural problem, we are hoping to build the expectation that coal companies have a responsibility to unemployed miners. In a sense, we try to be a strong, supportive, "public-interest" voice of coal-field communities.

For years, everyone associated with the coal industry — coal operators, workers, and state and local policy makers — has said that competition and unstable energy markets limit what coal can contribute to local development. Heavy environmental and social costs associated with mining have pitted environmentalists against the industry, labor versus management. You were for coal, or against it, and state policy was almost always designed to promote more production. Even progressive policy makers felt they had no other choice, and yet the environment still suffers, local governments are always strapped for funds, and workers never know how long they will be working.

MACED analyzed future employment in coal, assessing past and present productivity increases. We examined the impact of coal on local development during the boom times of the 1970s, and we interviewed leading coal executives about their community responsibility. Our analysis showed that even during the boom times, coal was not contributing to long-term development. Work and income were distributed unequally in coal areas, and this skewed distribution prevented substantial growth in earned income from improving poverty rates or basic conditions. We argued that policies to promote more coal production are not developmental.

Our reports emphasize declining employment, even as production remains steady, and we urge greater acceptance of public and private responsibility to assist displaced workers, their families, and their communities. But the reports also emphasize that hard-won environmental and health and safety regulations during the 1970s forced the industry to absorb costs previously left to workers and communities. The coal industry did improve its community impact. Some redistribution of coal benefits and costs occurred.

Furthermore, our interviews with coal industry leaders suggested that industry attitudes also had changed during the 1970s, and there might be greater sensitivity as well as capacity to deal with social responsibility. Certainly, there is now a sound precedent for public oversight and accountability.

My Turn: Closer to Home

I have a 19-year-old son, who's married, and has a child, and at this minute he's 45 foot underground in Leslie county. I fear for his future, because Eastern Kentucky is only one industry, and that's coal mining. All the small businesses depend on it, and they can't work without it. My son, I've tried to get him to go to school, but he'd rather make the big money that the mining companies offer him. I would sell my farm up at the head of McIntosh Creek, and get anything I could get out of it, if he would go to college. But he would rather make the big money. As far as his future, I've talked to him, and I'd say by 30 or 35 years he'll have black lung, and he will then depend on social security. And I just don't see no future for him, nor my grandson, and that scares me to death.

— Joe Whitaker, Kentucky

As a development organization, we are arguing that these improvements should be extended to local development. We are trying to raise public expectations of the industry without sounding an anti-coal alarm in the region in which it is the primary source of work. Coal will continue to be produced in Central Appalachia, at a steady pace. The question is still who will benefit. We think that the political climate in coal states may have changed enough to up the ante and start requiring that large and small coal companies extend their more socially responsible conduct to include local development issues. Through research and policy debates, we hope to advance the notion that coal can be more developmental. But we also emphasize that promoting more coal growth will not address serious unemployment problems in the coal fields. Coal states need to direct more energy and creativity to these distressed areas, or they will lose good potential workers to massive outmigration.

A sectoral intervention development strategy has the potential to build positively on sectors that already have a major impact. You try to rechannel a stream that is already flowing — you try to change not one logger but many, not one bank but 100, not one coal company but standards for the industry. In a similar tack, urban-based community organizations have accomplished developmental goals in credit and banking with the Community Reinvestment Act, which holds financial institutions responsible for local investment. Also, urban community development organizations have acted as real estate developers and housing managers to redirect resources to their constituencies. San Antonio COPS, a community organization, pressures local government to direct a share of the city's growth to their poor neighborhoods. In each case, community organizers and developers found critical levers which could be used to gain benefits for poor people and poor neighborhoods.

The strategy has not been applied very often in business development or in rural areas. We are trying it out. Business development in isolated areas is tough, and changing public attitudes about the redistributive role of government is a long-term political project. In the short term, we find that working to make incremental changes in critical, existing sectors can be a pragmatic approach to development.

Tags

Cynthia and William Duncan

Cynthia and William Duncan work at MACED. (1986)