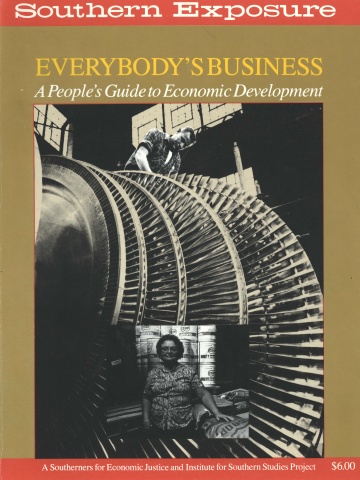

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 5/6, "Everybody's Business." Find more from that issue here.

Worker-owned enterprises are an example of the "alternative economic development" that many church groups are beginning to promote. Martin Eakes is director of the Center for Community Self-Help, a nationally known support group for worker-owned businesses in North Carolina. In a recent interview he talked about how churches can support this emerging movement.

Southern Exposure: Your program has been helping start worker-owned enterprises for the last six years. What makes them different from conventional businesses?

Martin Eakes: When you start a worker co-op, you're trying to create a culture within a business that is contrary to the dominant economic culture in society. You're basically trying to set it up so that as people learn things and grow into management positions, they come into a system that says you need to be accountable and responsive to the other people in the workplace.

SE: So you 're trying to change values?

Eakes: Completely. If you start small businesses that are focused on taking entrepreneurs and developing a business, you end up 50 years from now with the same set of problems that you had before. You have leadership that is responsive only to profit. People who have come through that workplace don't feel any responsibility to other people.

SE: Are there any assurances that you will be successful in changing values?

Eakes: The co-op model doesn't guarantee that you'll have an environment in which people can learn and teach. All it does is offer the possibility. A co-op is a structure that permits some kind of educational process to take place. It doesn't have to take place, and in fact it won't take place if you don't have leaders inside the business who are interested in playing the traditional role of management as well as being teachers.

Right now, we spend so much time just trying to help these small businesses survive that there has not been as much attention on educational development as we would hope. Many of the worker-owned firms started have been marginal businesses in low-profit or marginal industries; a cut-and-sew operation in the garment industry is a good example. You're always struggling just to survive. And because our primary focus is on the empowerment of the workers in that firm, we've given less attention to the critical need for management. In some ways we and other co-op groups have not fully recognized the critical role that leadership plays, even within a democratic context.

As a result, you do a lot of trial and error as a business, you do a tremendous amount of learning on the job. Frankly, unless they have a lot of grant money, most firms can't survive the cost of very much trial and error because of the market constraints from their competition.

SE: Where do you find management who will buy into a cooperative value system?

Eakes: People willing to come to the workplace as teachers are going to be coming out of some kind of value-based motivation. It's my feeling that the best place to search for potential managers for social justice enterprises is through the churches, particularly in the South.

A lot of people view the churches' primary role in an economic development enterprise as providing capital, which is very important. In North Carolina, there's not a single low-income co-op that has not received assistance in some form from the Campaign for Human Development, or the various agencies of the Methodist, Presbyterian, or Episcopalian churches.

But the place where the churches really have potential — and have not done anything thus far — is in attracting the leaders out of their own membership who could essentially be missionaries to the workplace, to a setting where people won't have to separate their work-life goals from the value system they practice through their religious activities.

SE: How would an interested church group know where to start?

Eakes: Co-ops can offer the opportunity and the linkages. For instance, we've got an opportunity right now for a great worker-owned business that would be able to market and distribute low-priced women's clothing. The sole thing lacking in that enterprise is a manager who's experienced in retail management. We need a network of churches that can say, "We're going to poll our membership for people who are early in their careers or later in their careers and who want a challenge where they can really teach people in the workplace and not just have the constraints of trying to make as much money as possible."

That's exactly what we need — some kind of system that can recruit people of good will to come and provide training and teaching. It would have to be a consortium of churches who have pooled their talents, and it would be a very gradual process. It would be like the church-sponsored housing work where people first go out and actually put bricks on a piece of ground. They've got to see the concrete effects of the work they do. Then they are able to come in and play a more significant role.

One idea I've had is to work with churches to try to build factories — basically a private, church-sponsored public works program. Through our credit union, we could help finance the materials to build these factories. Church volunteers could get involved, meet workers who are struggling to make a go of it, and perhaps gain a better vision of how their skills could be used.

The problem now is not a lack of good will; it's a lack of knowing what to do. There are lots of people interested in making an impact on what is truly a crisis of unemployment and underemployment, especially in rural areas. But they just don't know how to use their skills. Some kind of church program that gets people involved at an initial point, and then helps move them into management and leadership and teaching roles within a business would be wonderful.

SE: You've been known to criticize the concept of "empowerment of the poor." What do you mean?

Eakes: To say that we're trying to empower the poor seems to me to be very shortsighted. I can't count the number of people I know who grew up in dirt poverty, who have been empowered, who have become managers of small businesses, and who are more oppressive of their work forces than the people who were not "empowered." Power can be used for either good or for bad. If we build our ideology around trying to empower the poor (and that's what we talk about), then we've missed the critical half of bringing about economic justice — which is trying to maintain some sense of compassion, some sense of responsibility for those who remain poor once you have become empowered.

I'll give you an embarrassing example. There was a worker-owned firm that used the ideology of empowerment in reopening a shut-down grocery store. A very uplifting change of attitude. People started to view themselves in a wholly different light than they had before as workers in this grocery store. In time, the group of workers decided what they really wanted to do was to buy another grocery store, so that half of the worker-owners could go to that store and hire new employees who would not be owners. The ultimate goal was to split enough times so that every one of the initial worker-owners could become a single capitalist owner of a grocery store. Now on one level, that is empowerment like none of us have ever seen. But it illustrates how weak the concept of empowerment without more really is.

SE: How do you nurture alternative workplace values?

Eakes: In North Carolina, we have worked for the last six years on the premise that individual cooperative firms that are not linked together cannot survive as a teaching culture. That's because they exist in a system that does not value the teaching and development of leaders who may end up being competitors. You crack through that by having a network of firms.

You have the firms come together outside of their own setting, preferably twice a year. You need some process which takes people out of the day-to-day thinking about their jobs and the pressure of making a profit, which allows them to share their vision with people struggling with the same problems form other communities. We've found that when people get together with workers from other worker-owned firms, they tend to talk and to dream about their vision. Our goal, though, is not just to dream, but to go about doing something concrete.

Tags

Southern Exposure

Southern Exposure is a journal that was produced by the Institute for Southern Studies, publisher of Facing South, from 1973 until 2011. It covered a broad range of political and cultural issues in the region, with a special emphasis on investigative journalism and oral history.