Kids Are Work: Six Ways Child Care Creates Good Jobs

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 5/6, "Everybody's Business." Find more from that issue here.

Child care is a legitimate community economic development (CED) strategy for low-income women. Yet funders, economic development practitioners, local officials, and even women's advocacy organizations often deny requests for financial and technical assistance from child-care providers and advocacy projects. Why this opposition? Says Sophia Bracy Harris, executive director of the Federation of Child Care Centers of Alabama (FOCAL):

"Men, as well as women, are conditioned to believe child care remains the mother's responsibility, rather than a service absolutely critical to society. It is seen as women's work and thus not valued in economic terms. Furthermore, we lack the models of how child care can be translated from family providers to viable businesses. But not only is child care a critical service and a business, it is an industry that women can take control of."

1. Creates Jobs and Income

Child-care jobs are entry-level jobs, suitable to the skills and educational levels of most low-income women. Some critics of child care as a CED strategy argue that such entry-leval jobs are a poor alternative to public assistance. But child-care jobs also provide opportunities for personal growth and mobility. Many child-care workers in the 36 community-based centers belonging to the Rural Day Care Association of Northeastern North Carolina, for example, began as CETA or JTPA trainees, went on to earn their GED, and eventually qualified for the national Headstart Program credential. Child-care workers often develop their skills and later become center administrators or managers of their own centers or home-based businesses.

Child care is a demanding occupation, requiring women to develop a wide range of skills and knowledge that can be translated to other employment situations. Such skills include expertise on infant and child development, children's diseases and illnesses, food preparation and nutrition, first aid, activities planning, record keeping, and interpersonal skills.

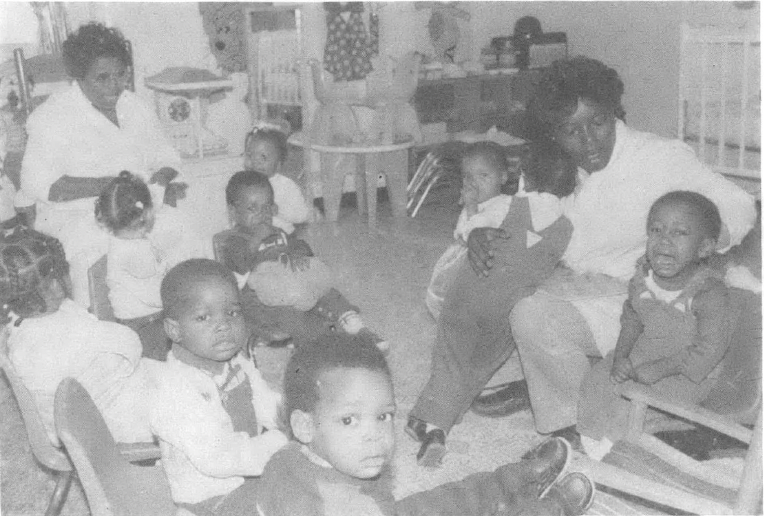

Child-care ventures are also labor-intensive operations, with the potential to create large numbers of jobs. Most state licensing laws require ratios of one adult child-care worker for every four to six children. The 36 community child-care centers in northeastern North Carolina, for example, employ 170 women, all jobs created within the past five years. Though this record cannot compete with Perdue, Inc., whose poultry processing plants in the region employ 3,200 (mainly women) workers, these child-care jobs are vastly superior in their opportunities for training and mobility, in their security, in their relative freedom from health hazards, and in their social importance.

Besides the staff jobs, child care makes it possible for low-income women to work. In northeastern North Carolina, 60 to 75 percent of the 1,900 children served through the Rural Day Care Association's centers come from single-parent households. It is reasonable to conclude that most of these mothers would have great difficulty in securing reliable, decent, affordable, and full-time child care were it not for the Rural Day Care Association's centers. At any point in time, therefore, approximately 1,000 poor, minority women are able to work because their children attend community child-care centers.

Politicians understand the link between child care and economic development, as a recent incident in North Carolina graphically demonstrates:

Alternatives for Children, a community-based organization in Gates County, opened two day-care centers in 1977 following two years of hard work. Situated in the far northeastern corner of the state, the county is poor and primarily black. Most of its residents commute to neighboring Virginia for work. Until 1981 Gates County had no industry.

In 1981, the North Carolina Department of Human Resources told Gates County that it had no more money to support its day-care centers. The centers were almost entirely dependent on state subsidies. Parents were notified by the Department of Social Services that the centers would close in ten days. Meetings were set up with local and state officials, but to no avail.

The next week, Governor Jim Hunt came to Gates County to cut the ribbon for the county's first industry, a cut-and-sew plant which, incidentally, was hiring all women. Local dignitaries were not the only participants at the ceremony. The 50 children served by the centers also came, bearing signs which read, "DAY-CARE FOR WORKING MOTHERS, KEEP OUR DAY-CARE CENTERS OPEN." The governor promised that he would do what he could. That next week, Alternatives for Children was told that the state had found enough money to keep one center open. And somewhere close to 25 mothers were able to work at the new apparel plant.

The Home-Based Provider Network

The vast majority of child care in this country is delivered by home-based providers. (North Carolina law generally limits home-based care to five full-time children; most states have similar limits.) Though serious questions about the quality and even adequacy of this type of care are raised, parents often prefer home-based care. It can provide more flexible operating hours, it may be geographically convenient, sick children can be more readily cared for, it is generally cheaper, and the setting is more intimate than center care.

From the provider's perspective, the licensing requirements of home-based care are less strict, complex, and costly. The provider can turn her own home into an income-producing asset while caring for her own children as well. Finally, home-based care can serve small numbers of children and requires only minimal investments in furniture and equipment.

Like most marginal small businesspeople, home-based providers usually lack the resources and the time to obtain extensive training in child development, business management or financing. However, an umbrella support organization like the Community Improvement Coalition of Monroe County, Georgia can provide such training, technical assistance, and advocacy, much as the Rural Day Care Association and FOCAL provide these services for center-based providers.

Located near Macon, Georgia, the Community Improvement Coalition of Monroe County serves as the sponsoring agency for 20 home-based providers — all low-income black women. Because this group is able to serve as a sponsoring organization, the home-based providers can participate in the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Child Care Food Program. This means that each provider is reimbursed approximately $2.20 per child for meals. For a provider serving five children, this program provides an additional $212 per month for five children, or $2,544 per year.

The sponsoring organization's responsibilities are not burdensome. It must regularly monitor the nutritional content of the food as well as provide training in child nutrition. The benefits to the sponsoring organization are ample. The Community Improvement Coalition receives $50 each month for each provider enrolled. With 20 home-based provider members, this means $1,000 per month for the organization. This $1,000 can support a staff person who can both oversee the nutritional programs of the home-based providers and provide training in child development.

Broader roles are possible for the community-based sponsoring organization. It can provide health screening, with reimbursement from the Medicaid-funded Early Period Screening and Diagnostic Testing (EPSDT) program. Technical assistance in marketing, business management, financing, and ongoing program enrichment can be offered. A resource library of toys and other learning aids can be developed. Finally, the support organization can establish quality control mechanisms to strengthen the reputation of each individual provider.

Home-based care need not simply be a form of income supplementation for women. ASIAN, Inc., a community organization based in San Francisco, estimated in 1981 that a provider serving six infants and toddlers who participated in the USDA Child Care Food Program could net $15,000 income per year. Though the going market rate for home-based care in rural areas in the South is probably two-thirds of the rate estimated in the California study, a $10,000 net income in 1981 dollars is still a substantial income for most low-income women.

Finally, child-care operations require little capital investment for the number of jobs they create. The estimated cost of opening a center that serves toddlers in northeastern North Carolina is currently $8,000 to $10,000. In almost every case, facilities are donated, loaned, or leased, and renovations are achieved through volunteer labor and free materials. Thus a job can be created at a unit cost of approximately $2,200. In contrast, the unit cost of creating a job at a worker-owned hosiery mill in North Carolina in 1984 was approximately $17,000.

Income supplements should be a critical component of any women's CED strategy, particularly in rural areas. Child-care ventures can effectively supplement the incomes of low-income women by providing opportunities for part-time work, particularly in home-based situations. Not only do home-based providers get actual cash income through fees, but they can reduce their income tax payment by deducting on a prorated basis some normal living costs as business expenses, as well as by taking depreciation allowances on equipment, appliances, and furnishings. Such supplements often mean the difference between mere survival and a decent standard of living.

2. Fits into a Growth Industry

There is no question that a growing demand for child care exists. Nationally, over nine million children under the age of six have mothers in the labor force. Projections for 1990 yield almost 3.4 million more children under six with working mothers, a 38 percent increase since 1980. In the years between 1970 and 1984, the percentage of children under three with working mothers rose nearly 30 percent; that increase was 95 percent for children under one year of age.

Corporate America recognizes the profit and growth potential of the child-care industry. Kinder Care, based in Montgomery, Alabama, owns and operates more than 1,000 centers nationwide. Other for-profit child-care companies with exceptional growth records include Daybridge Learning Company (a subsidiary of ARA), Gerber Childrens Center (a subsidiary of Gerber Foods), La Petite Academies, and Children's World (a subsidiary of Grand Met USA). These four companies each own and operate hundreds of child-care centers.

Moreover, this demand is fueled by both the private market and a public subsidy system. Two-parent professional working families create a rapidly expanding private fee market, stimulated by child-care tax credits at the federal and sometimes the state level. Public funds from the federal Social Services Block Grant program and from state appropriations help to support child-care slots for low-income children. Though woefully inadequate, such public funds provide a source of income for community-based centers and individual providers serving low-income, particularly female-headed households. It is important for low-income communities to capture these public funds which, in some states, can go to for-profit providers, or which fail to reach the community at all when no certified centers exist.

3. Serves Low-Income Community Needs

The lack of decent and affordable child care is frequently the greatest barrier low-income women face in securing employment. After pleading and begging their mothers, neighbors, aunts and grandmothers to babysit one more time until other arrangements can be made, women often are forced to quit working. In 1983, two-thirds of the women in the labor force were either single, widowed, divorced, or married to a man whose income was less than $15,000. A great proportion of these women headed single-parent households. In 1983, one in five children lived in a single-parent household. This number is projected to increase to one in four children by 1990. It is clear that low-income women sorely need decent, affordable child care for their children if they are to go to work.

The problem also exists for working-class families, caught in the squeeze between ineligibility for public subsidies and the unaffordable fees of center-based or other quality child-care arrangements. Although they usually can afford to pay, even middle-class families often cannot find satisfactory child-care arrangements, particularly for infants.

The need for child care is both a quantity and a quality issue. There are 22,000 licensed child care centers in this country today, about half of which are for-profit operations. Assuming that each center serves an average of 25 children, this means that 550,000 children are now attending child-care centers. Surely those remaining 8.5 million children under six with working mothers are not all adequately served by the extended family, individual providers, or exempt church-run centers.

4. Develops Management and Entrepreneurial Skills

A CED strategy seeks to develop opportunities for increasing the management and entrepreneurial skills of low-income community members. Child-care center managers frequently come from the ranks of child-care workers, community activists, or concerned parents. Home-based child-care providers are, in fact, independent, self-employed small businesspeople. There are few other opportunities in low-income communities for women to develop the skills needed to manage or own ventures that are self-sustaining and sometimes even profitable.

An Effective Voice of Unity

Northeastern North Carolina is poor. Seventeen of the 18 counties represented by the Rural Day Care Association have poverty levels higher than 20 percent. Though black people are 40 percent of the population of this region, they comprise 90 percent of those living in poverty. Such poverty is perpetuated by poor schools and high dropout rates, inadequate health programs and disproportionately high rates of illness, and "economic development" efforts which manage only to recruit more low-paying, labor-intensive industry into the area.

In the late 1970s, grassroots efforts to create and provide child care for poor families existed through a patchwork of black community-based child-care centers. Directors of centers separately struggled to raise the funds to obtain certification for the Title XX child-care slots that help low-income families to afford child care. At the same time, many of the northeastern county social services departments were returning child-care funds to the state, citing a lack of need for this money.

In 1978, center directors met with other concerned people — parents who worked for minimum wages miles from home and who could not afford child care, teachers hoping to better prepare black students for public school, and child-care workers frustrated by the lack of adequate resources and facilities. The creation of a united voice for child care — the Rural Day Care Association — emerged from these meetings. Today, the Rural Day Care Association is guided by its board of directors — child-care center directors from each of the 18 counties included in the association. Some of their accomplishments are listed below.

Development of a strong alternative delivery system of child care. In 1977, there were seven certified child-care centers providing subsidized care in all of northeastern North Carolina. Today there are 36 certified centers serving 1,900 children and their families, including five new Headstart programs. These centers have directly created more than 170 much-needed jobs in the region. Moreover, it is estimated that these 1,900 slots bring in $3.8 million annually in subsidies to the region. The 170 workers add nearly $2 million in payroll, while those mothers who otherwise would not be able to hold down jobs bring in approximately $10 million to the region. In sum, the Rural Day Care Association delivers more than $12 million to northeastern North Carolina, and also provides summer child care and health services to 45 children of migrant workers in two counties.

Local, state, and regional advocacy for increased child-care funds for the region. The Rural Day Care Association challenged the state's annual allocation of child-care subsidies on the basis of population density rather than need. This system traditionally benefitted North Carolina's growing and more prosperous metropolitan areas, at the expense of poorer rural areas. As a result of advocacy efforts, the Office of Day Care Services initiated a special project in 1981 to develop child care programs in underserved areas of the state. Ten counties in the northeast were targeted and $300,000 was set aside for start-up grants. 1984 was the first year that each county in the northeastern region used all of its child-care allocations. And in response to local advocacy efforts, many counties have requested additional funding. Finally, in 1985, the state legislature changed the formula for allocating child-care funds so that 50 percent of the allocation is now based on need. It is estimated that the northeastern region of the state is now eligible for more than $2 million in additional child-care subsidies.

Education of Public Officials. The Rural Day Care Association has also challenged local governments to support child care. One association board member convinced the city of Roanoke Rapids (home of the J.P. Stevens labor union fight) to apply for a child-care center startup Community Development Block Grant. The grant was written and approved, a new center was built, and the center is run by a charter member of the association's board.

Education of local officials about the importance of child care has been a priority of the Rural Day Care Association. Sprinkled throughout the hundreds of members attending the association's annual membership meeting are county commissioners, city council members, state legislators and even a Congressman or two. Northeastern North Carolina Tomorrow, a regional commission which generally focuses on traditional economic development strategies, has elevated the issue of child care from a "welfare problem" to a viable development approach. The commission's plan of action now includes a resolution to develop funding for community-based child care in the region.

5. Promotes Community Control

One primary goal of a CED strategy is to increase the control of a low-income community over its resources and institutions. Nothing is more important to the future of a community than the development of its children. Most communities have little control over the schools that their children attend. They can, however, readily control the community's preschool institutions by creating community-based child-care centers or by bringing home-based providers into a community-supported network.

In northeastern North Carolina, community child-care centers have provided an opportunity for women to develop skills which are then used in other economic and political arenas. To survive, these centers have to act as effective advocates before local and state governmental bodies and with local social services agencies. The experience of public advocacy for child care has been critical to the development of minority women leaders in the region. In Alabama, for example, the Federation of Child Care Centers devotes much of its resources to its Black Women's Leadership and Economic Development Project, believing that change at the local level, in child care or in any other facet of life, will come about only if community people realize their own power and potential.

6. Stimulates Ancillary Businesses

In developing a comprehensive CED strategy, the community must look at the potential of any venture to create spinoffs that it can own and operate. Child-care ventures have the potential to generate service ventures such as food preparation, health screening, and transportation; and production ventures such as the manufacturing of toys, playground equipment, and furniture. The Rural Day Care Association of Northeastern North Carolina, for example, is studying the feasibility of a playground equipment manufacturing venture to help support its operations. The idea came to the association after it realized that it had paid hundreds of dollars for a piece of playground equipment that can be made for less than $20.

The Barriers

In sum, child-care ventures make good sense as projects for low-income women. But why has development been so limited? What are the barriers to creating child-care ventures in the face of growing demand, clear-cut need, and ability to pay?

The first and possibly most important barrier to the development of community-based child-care ventures is attitude. Child care is not perceived as a legitimate economic development venture and thus it is denied assistance from those church, foundation, and government funding sources that give money to economic development projects. This attitude stems from the belief that as women's work, child-care jobs are not real or remunerative jobs. There is no question that child-care providers are poorly paid. All work, however, that was originally provided by unpaid labor in the home is poorly paid. In fact, child care pays as well as most manufacturing jobs held by women in the South.

Other barriers to the development of community-based child-care providers include:

• the difficulty of locating suitable facilities available for center-based care;

• the costs of acquiring, renovating, and equipping centers relative to the resources available to the community;

• the detailed government regulations which affect the start-up, acquisition, and ongoing operation costs;

• the government licensing regulations and processes which greatly discourage potential child-care providers;

• the rising cost of insurance coverage;

• the lack of knowledge needed to start up and operate a child-care facility; and

• the low wages, social value and self-esteem associated with child-care work.

Strong support organizations for child-care providers can overcome these barriers. But their establishment will require the commitment of local providers and concerned citizens, as well as the financial support of churches, foundations, and other community-oriented funding sources. The payoffs can be substantial. Not only has the Rural Day Care Association of Northeastern North Carolina, made it possible for more than 1,000 single parents to work, but its advocacy has meant millions of dollars more for subsidized child care in a poor remote region of North Carolina.

Tags

Deborah B. Warren

Deborah B. Warren is the community economic development specialist for the Legal Services programs in North Carolina. Information about the Rural Day Care Association was provided by Carol Solow, now working in Seattle with the Washington Association for Community Economic Development. This article originally appeared in a special edition of Economic Development & Law Center Report on women. This Spring, 1986 issue is available for $3 from the National Economic Development Law Center, 1950 Addison Street, Berkeley, CA 94704. (1986)