This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 5/6, "Everybody's Business." Find more from that issue here.

". . . a Merrill Lynch 'Confidential Private Placement Brochure' distributed to selected Merrill Lynch investors proposes raising the money to acquire prime land at currently depressed prices, grow high-value crops, add processing facilities and sign supply contracts with food companies. The organizers say they hope to get a 20-25% return to investors annually. . . .

"It contends that most farmers have neither the finances nor the experience to switch from producing grain and soybeans to vegetables and other high-value crops and that farmers can't realize economies of scale through integrated farming. And most farms, adds Merrill Lynch, are neither large enough nor sufficiently capitalized to get supply contracts with major food companies."

Food & Fiber Letter

June 9,1986

This is Merrill Lynch's version of how American agriculture should be restructured to benefit an elite group of absentee investors. It is a dismal vision of a future that leaves no place for community values or stewardship of the land. Some specific investments for Texas illustrate what Merrill Lynch has in mind:

"Among the possible projects: a 12,800-acre potato production and processing facility in northern Texas or eastern Colorado, a Texas Gulf Coast shrimp hatchery and processing operation, and an 11,000-acre vegetable operation in the Rio Grande Valley."

If Merrill Lynch seriously intends to peddle its absentee-investor strategy for revamping agriculture in Texas, it will quickly discover that there is another strategy being pursued in this state. Instead of dismissing family farmers as outmoded enterprises incapable of fitting into a sophisticated, market-oriented food system, the indigenous Texas strategy says that a joint effort of government and small farmer-owned businesses can put together the necessary financing and expertise to allow small farmers and local communities to build tomorrow's agriculture on the democratic values of the family farm system. It is a vision of an agriculture economy in which those who do the work earn the profits, where ownership is decentralized in small- and medium-size businesses, and where profits are retained in the local economy.

A Born-Again State

In January 1983, after the election of Jim Hightower as Texas Agriculture Commissioner, a group of us took charge of a sleepy, go-along-to-get-along state agency. Since then, we have redirected the Texas Department of Agriculture (TDA), bringing in new staff, new constituencies, new ideas, and a new spirit. One of our goals was to make TDA a problem-solving partner to assist grassroots economic development.

We identified three broad areas in which a state department of agriculture could focus on making an economic and social impact:

Marketing. Government agriculture programs traditionally have been concerned almost exclusively with production rather than selling. We wanted to plug family farmers into markets — local, state, national, and even international. Our objective was to organize new marketing channels so that family farmers could sell their products as directly as possible to the ultimate buyer, bypassing some middlemen and thus getting a better price for their products.

Diversification. If farmers aren't making money on cotton, corn, and cows, then TDA should help identify commodities that are profitable for farmers to produce in Texas and design strategies for marketing those crops.

Agricultural Development. Since 75 percent of the consumer food dollar goes to the processors and marketers of food, it makes economic sense to help family farmers move into these ''value-added" enterprises. The role of TDA would be to assist in packaging such homegrown businesses.

Working in those areas, TDA has been able in a surprisingly short time (three and a half years) to launch dozens of successful projects with very little taxpayer cost. The sum is even greater than the parts, for the projects often complement each other, are structured from the start to allow for expansion, and are intended to result in forming whole new marketing systems.

For example, helping a farmer to diversify into the production of specialty crops could then encourage several other area farmers. With higher production volumes, these farmers could form an association to wholesale directly to chain store markets, and ultimately could build a cooperative facility for processing those crops. Overall, TDA's direct marketing, crop diversification and agricultural development projects add up to a statewide economic development program that already is generating millions of dollars in new wealth through small enterprises.

Marketing

Farmers traditionally have been asked to produce in great volume and to hope that a market and a fair price would exist for their commodities. We worked to reverse this notion: find a market willing to pay a fair price, ask farmers to produce for it, and help them sell directly into that market.

We started small and simple with old-fashioned farmers' markets. Drawing on the organizing experience of a new staff, TDA offered to work with any local government or citizens group interested in starting a farmers' market. We worked through city councils, county commissioners, "main street" projects, chambers of commerce, etc. Demand was strong. Even in our late-starting first year, 1983, the idea had enough appeal for us to launch four markets. In 1984 there were 17 markets, the next year there were 34, and in 1986 there are 48 markets, ranging from cities the size of Houston and San Antonio to the small towns of Cuero and Sweetwater. The markets are a success. Farmers can more than double the price they receive from a wholesale buyer, consumers pay less and get high quality produce to boot, and the local area retains the money that changes hands and gains the intangible boost of having a colorful, festive market.

Critics have complained that farmers' markets are not the answer to the state's agricultural woes, which is true, but they certainly are a big answer for the hundreds of family farmers who sell at these markets. Those producers will split around six million dollars in sales this year and average about a one-third increase in their net incomes over last year. Some farmers have even cut back their off-farm work in order to sell in two or three markets in their area. The beginnings of a statewide farmers' market network has great potential for spreading the word about the rewards of selling directly to consumers.

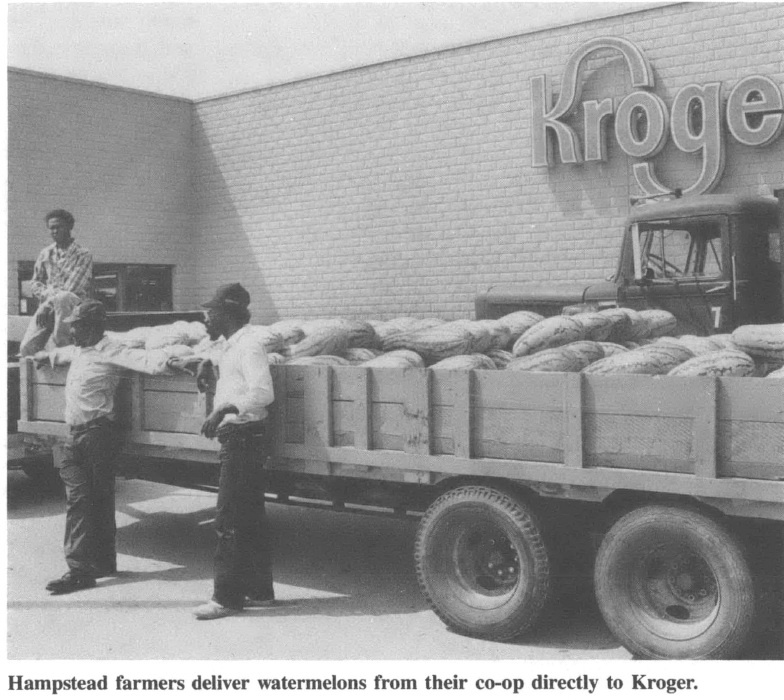

Another promising effort has been to organize cooperatives of farmers to produce specific commodities for sale directly to such lucrative markets as chain groceries, processors, restaurants, and governmental feeding programs. Our first major success was with a group of black farmers in Waller County, just outside of Houston. This is a county renowned for the quality of its watermelons, yet in recent years these farmers had seen 60 percent of their crop rot in the fields for lack of an outlet. They had sold the other 40 percent out of pickup trucks on the roadside, getting only one-to-three cents a pound.

Meanwhile, we learned that Kroger was hauling watermelons from Florida to sell at its 103 stores in the Houston area. Not good. We paid a visit to Kroger's produce buyer, asking why they were not buying locally. We learned (1) that Kroger couldn't be running up and down the road buying watermelons, (2) that they needed a substantial volume and (3) that they wanted a 27-pound melon. In response, we said (1) we'll organize a melon cooperative so Kroger could deal with a single supplier, (2) the Waller County farmers had enough melons rotting in their fields to meet Kroger's need, and (3) the cooperative would hold their melons back to 27 pounds. We gave them a taste, and they took a truckload.

In 1984, the first year of this cooperative, the farmers sold all of their crop to Kroger — 500,000 pounds. And rather than the one-to-three cents a pound they had been getting, they got seven cents, generating a 165 percent increase in their average net income. Consumers got a good deal too, because instead of paying $3.50 for a travel-weary Florida melon, they could buy tasty Waller County melons for $1.98. And the money they spent stayed in the local economy.

The sale was not a one-shot deal. Kroger liked this new marketing channel. In 1985 they bought one million pounds of melons from the cooperative and this year they will buy two million pounds. More important, based on the successful model of the Waller County producers, TDA was able to encourage other small producers to organize cooperatives as a way of tapping into direct wholesale markets.

Last year we worked to help a group of low-income Mexican-American producers organize as the Rio Grande Valley Farmers Cooperative. Our initial role was to link them into a sizeable retail market. Pathmark, a supermarket chain operating in five Northeastern states, became their first buyer, taking several truckloads of vegetables in the fall of 1985. Pleased with the cooperative's product and performance, Pathmark is negotiating to purchase from the Valley farmers this season. Not only does this open a market that otherwise would not be available to small producers, but it also offers a profitable market. Previously, Valley farmers have had to sell to one of a handful of local packers and shippers, generally receiving a very low price. By selling directly to Pathmark, they are getting around the middlemen and getting as much as three times the price set locally.

The cooperative's second buyer was Pace Foods, Inc., a San Antonio firm that specializes in bottled picante sauce and other packaged Mexican foods. Through our promotional work with Pace we learned that they were buying out-of-state jalapeno peppers during the fall and winter because they were unable to find a local supply during these months, even though it is possible to produce for the fall season in the Rio Grande Valley. The cooperative was able to move into this market niche.

The point is not merely that a number of farmer-owned marketing cooperatives have been successfully launched in the last three years, but that an entirely new system of food wholesaling is being established. In addition to supermarkets and food processors, such giants of the institutional food market as Sysco and Fleming are now interested in buying fresh supplies directly from local producers. TDA is helping Texas farmers break into the centralized procurement systems of these corporations by organizing a localized system that is easy for these firms to use and offers genuine business advantages for them.

Diversification

The prices that farmers are receiving these days for such staple commodities as wheat, rice, cotton, sorghum, and corn are generally far below the cost of producing them, which is a major reason so many farmers are going broke. One way to help farmers deal with the devastating impact of low prices on their income is to encourage them to diversify their operations by shifting some of their acreage to the production of higher-value specialty crops. Instead of simply being dependent on the prices of beef, hay, and milo, for example, an East Texas farmer operating 200-300 acres might convert some of those acres to blueberries, Christmas trees, or sweet grano onions. The farmer might put in a catfish pond or produce a flock of organic poultry. If he or she has the calling he might do it all.

TDA has tried to make diversification a real possibility for Texas producers by first identifying market interest in a local supply of these products, and then by finding "pioneers" with the vision, guts, and financial capacity to take the production risk.

Some alternative crops were already being tried on a small scale when we entered the picture. Blueberry production, for example, was being encouraged by Texas A&M's research and extension staff. A small number of East Texas farmers and nurseries have been producing berries the last few years for sale through pick-your-own operations and roadside stands. A TDA-sponsored marketing study concluded that Texas-grown blueberries had a potential commercial market of about $50 million annually, thus legitimizing the crops as worthy of serious consideration by East Texas producers.

As a start, TDA began working with supermarket chains. We piqued their interest in the Texas berry by holding blueberry tastings for produce buyers. In 1985, TDA's promotion staff generated newspaper and magazine articles about this new crop and appeared on radio and TV talk shows to let consumers know something new from Texas was on its way. In the summer of 1986, the first load of Texas blueberries was delivered to a Fort Worth-area supermarket where they quickly sold out.

About 15,000 pounds of berries will be sold directly from farmers to supermarkets during the year, with 75,000 pounds due in 1987, and this is only a scratch on the retail surface. With marketing possibilities from pick-your-own to frozen berries for institutional use, blueberries have the potential to become one of the state's largest horticulture crops.

My Turn: Closer to Home

I'm that curious sort of farmer that doesn't have a farm. My wife Pat and I sold the farm in August. We had 244 acres of mostly steep pasture land sort of farm, about five miles southwest of Rural Retreat, in Wythe County. We kept about 30 beef cows, about 100 ewes. We sold that farm because we were getting in debt, a little more every year.

The house we lived in won't be occupied. There won't be anyone from that house to give blood when the bloodmobile comes to Rural Retreat, or anyone to support the fire department or the rescue squad. There won't be anyone to play Rook or coon hunt with the neighbors. There won't be anybody to buy groceries at William's Supermarket in Rural Retreat from that house, or have feed ground at Rural Retreat Mill. In the past ten years, Rural Retreat has lost a hardware store, a department store, one grocery store, the Esso station.

It's not a nice thing to happen to a farm couple, either, when you've done it all your life and you think it's the finest thing a man and woman can do together, to farm. When you fail, there's depression that comes along, and all the friends that are still out there farming are a reproach to you.

— Buddy Mitchell, Virginia

Pinto beans — the simple frijole — is another item now catching the attention of farmers eager to find a profitable crop. In this case, TDA was starting from zero — there were not even experimental efforts underway to produce pintos in Texas for commercial sale. But the market for pintos is huge in our state, since the humble legume is a dietary staple for the three largest cultures: Southern Anglo, Mexican American and Afro-American. Texas consumers and food companies use 100 million pounds annually. Unfortunately for the state's farmers, practically all of the pintos sold in Texas are grown in Colorado.

In 1985, TDA started with a lone farmer in Ochiltree County willing to plant the first commercial crop. His is a large family farm operation, as they tend to be on the flat expanses of the northern plains of Texas. But like so many of his neighbors, he was losing money fast in the wheat and cattle business that dominates agriculture there. He rolled the dice with us and planted 400 acres of pintos. He made a good crop and TDA helped him market it to nearby Arrowhead Mills. He also made a per-acre profit far better than any other crop in that region.

The beauty of pinto beans is that they can be double-cropped or alternated with wheat, providing a second cash crop for farmers. Another advantage is that standard production equipment can be used, keeping the initial investment low. This year TDA is working with 150 farmers in Lamb County who are growing pintos and with area processors who are converting cotton delinting facilities to handle pintos. TDA will provide marketing assistance in finding buyers throughout the state.

These are just two of dozens of crops that can help family farmers shift from depending on monoculture or duoculture. TDA is also encouraging farmers to look at diversification into such crops as Christmas trees, organic produce, grains and meats, grapes, jojoba, oriental vegetables, native plants and Texas-grown nursery stock, crawfish, and apples, as well as such specialty crops as herbs, sprouts, and "boutique" onions.

In all of these cases TDA starts with the identification of a market, helping producers establish links to a buyer before investing in production. That might seem to be an obvious first step for a business, but it is one that has often been overlooked in agriculture, with the result that farmers produce a perishable crop, then beg someone to buy it from them at any price. Individual small- and medium-sized farmers have no entree into the offices of corporate buyers, so state government can perform a useful role by making that connection.

Agricultural Development

Food and fiber processing is an industry that offers an opportunity for grassroots economic development on a micro scale, and the chance to generate a major resurgence in a state's economy on a macro scale. To put it simply, hundreds of small locally owned processing facilities scattered throughout the state can generate hundreds of millions of new dollars and thousands of jobs for the state's economy. TDA estimates that every one percent of the current national food processing market represents 35,000 jobs, $3 billion in earnings, and $9 billion in economic impact.

State and local governments wanting to "develop" this kind of economic potential usually offer incentives to established corporations to move into their area. Governments have offered such bait as land, water, buildings, rail spurs, cheap labor, employee training, tax breaks, university research, zoning exceptions, and low-interest financing to entice some Fortune 500 firm to come make money from the productivity of local people and resources.

Rather than trying to lure conglomerates to Texas to process farm and ranch commodities, we asked, why not use the resources of government to help farmers and local businesses become processors themselves? By investing in our own people, not only would income and jobs be generated, but this new wealth would remain in the local economy.

In the Texas Panhandle, for example, in the town of Dawn, nine wheat farmers joined forces in 1985 to build their own flour mill. Their motivation was necessity, since wheat prices had deteriorated to a level below their cost of production. Plain wheat flour, which was selling for 26 cents per pound to wholesale buyers, was returning only five cents to wheat producers. TDA conducted an assessment of the demand for bulk sales of flour in the area and learned that a substantial market existed for locally produced, high quality flour to be sold wholesale to bakeries, restaurants, colleges and universities, tortilla manufacturers, etc. The nearest flour mill to this region is 250 miles away. Some of the buyers were interested enough in having a local supplier that they were willing to sign advance purchase agreements.

Based on this market assessment and on a cash-flow and income analysis that TDA staff prepared for the farmers, the Dawn flour mill project obtained financing and a groundbreaking ceremony was held just before Christmas 1985. The facility, which will produce 300,000 pounds of flour a day, will mill its first flour in early 1987.

In the national scheme of flour milling, the mill at Dawn is hardly significant, but in what it represents to the economy of the area and to the idea of grassroots economic development, a farmer-owned mill is a very big deal indeed. For top quality wheat, the mill intends to pay a premium price to other area farmers, representing a 50 percent increase in the farmers' share of the wholesale value. The mill is projected to generate $10 million a year in sales, 14 direct jobs, and 20 indirect jobs.

The idea of small-scale development is becoming attractive to many individuals and communities in Texas. Near the north Texas town of Childress, Minnie and Bill Bradley run a modest ranch called the B3R. They were fed up with selling their cattle for 55 cents a pound and buying beef for $3 a pound, so Minnie began investigating the possibilities of doing some of her own processing and marketing. TDA worked with the family helping them develop a sound business plan, then helping obtain the needed $940,000 in financing.

For this relatively small investment of capital (as compared to the meat packing industry), the Bradleys' present cow-calf operation will be expanded into a fully integrated meat business, specializing in high quality natural, corn-fed beef. They will expand their feed lot to handle 3,000 head of cattle a year; they will buy cattle from local ranchers and corn from local farmers; they will build a slaughterhouse and meat packing facility; they will have a retail outlet; and will sell their own brand-name meat to grocery stores and restaurants within a 45-mile radius of Childress. This one venture will create 40 new jobs and inject more than $2 million annually into the local economy.

In themselves, the B3R venture and the Dawn flour mill are not of national importance. But they demonstrate that by putting the business tools of market assessment, cash-flow analysis, and capital formation in the hands of people at a local level, a state agency is able to help people help themselves and to nurture the aspirations of hundreds of small- to medium- sized enterprises at home. In 1984 and 1985, TDA helped to generate $65 million in capital investment for grassroots enterprises that will produce first-year sales of $260 million when completed.

Keys to Homegrown Success

We are often asked — usually by people who are shocked that an agriculture department in Texas could initiate progressive programs and live to tell about it — how TDA got the momentum started. It takes commitment to the idea that government can help foster grassroots development. It requires recruiting people who believe in such development and who have the skills to do the necessary organizing and the stamina to face obstacles without getting discouraged.

It also takes patience. Building a progressive agricultural alternative for the future is a long-term process. Skepticism is rampant in the press, in the financial community, in the political world, and even in the farm and ranch communities. We had to start small and build by demonstrating success. There is nothing like positive results, even on a small scale, to win converts. Rhetoric is not enough, good intentions are not enough. We took a project approach and gave ourselves the time to take risks and nurture the projects we started.

The project approach is an effective way to marshal resources and focus technical assistance. The assistance TDA provides runs the gamut from market studies to promotional campaigns, to business plans, to management training, to financial packaging assistance. What works best is what is practical and suited to the needs of each specific enterprise.

When we began in Texas, there was no master plan at work, but there was a sense of urgency to prove that homegrown small enterprises can be a realistic avenue for economic development, not only for family farmers and rural communities but also for the state. Every day we fought the conventional wisdom that development means wooing mega-firms to Texas. But we also had that maverick "what-the-hell, give-it-a-try" Texas spirit working in our favor.

So we found allies. By using the good offices of TDA, we were able to open doors and get the cooperation of other folks — people in both the private and public sectors who could play a key role in making an alternative vision of economic opportunity a reality:

• a local independent banker in Colorado County whose bank financed the state's first agricultural development bond project, a farmer-owned rice dryer facility in Eagle Lake;

• the cooperation of the Texas Department of Community Affairs and the City of La Villa in providing funds to make low-interest loans available to local vegetable producers to build a grading, packaging, and processing facility that will have a projected payroll of over $1.5 million a year;

• the participation of private developers, the state highway department, and the state purchasing agency in TDA's "landscape with native plants" campaign;

• the Rouse company, through a locally owned shopping mall, providing space, tents, staff, publicity, and even clowns to help get the Austin farmers' market off to a dazzling start;

• a grant from the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department which makes it possible for TDA to begin a seafood marketing and promotion program.

These and hundreds of other people and institutions have been the crucial part of TDA's experiment in "homegrown" economic development. Don't let people tell you it is strictly bottom-line dollars and cents that sells a business concept. Certainly, business people do not want to lose money. Making a profit matters, but there are also other powerful motivators such as community loyalty, public relations, the challenge, fun, and sometimes just plain stubbornness that are part of the decision to go ahead with an idea.

Every step away from the "what is, therefore, must be" way of thinking moves us closer to finding creative, democratic, humane solutions to our economic woes. We have a small beginning here in Texas but it is an endeavor worthy of the effort.

Tags

Susan DeMarco

Susan DeMarco, former Assistant Commissioner for Marketing and Agricultural Development in the Texas Department of Agriculture, is currently doing consulting work. (1986)