This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 5/6, "Everybody's Business." Find more from that issue here.

Watching television on July 30, 1985, Spring Hill Mayor George Jones first learned that General Motors would build the world's most expensive manufacturing plant in his middle Tennessee community, population 1,275. By that point, GM's Saturn plant had been the object of a seven-month industrial recruiting contest involving 1,000 sites in 36 states, a parade of governors bearing gifts, and impassioned pleas from chambers of commerce, local citizens, and school children.

Saturn didn't choose Minnesota, which offered tax concessions and other prizes worth $1.3 billion, or Kentucky, which legislated a $306 million educational aid package after word leaked out that GM considered the state's school system inadequate. Instead, it selected a sleepy town 30 miles south of Nashville. At the time, Spring Hill didn't even have a full-time police officer, fire fighter, or physician. The announcement, said Mayor Jones, was like something "falling from the sky."

The Deal

General Motors planned the $3.5 billion Saturn plant as its main bulwark against the Japanese car invasion. With significant assistance from the UAW, GM created the Saturn Corporation as a separate subsidiary to produce up to half a million subcompacts a year with about one-third the workers needed at similar GM facilities. Limited production is expected to begin in late 1989. When the plant reaches full capacity (some years later), GM claims that it will provide 6,000 direct jobs and 12,000 to 14,000 additional jobs among suppliers, service firms, groceries, eating places, and the like.

In choosing middle Tennessee, GM joined a South-bound migration of automakers that included a Nissan plant at Smyrna, Tennessee (just 30 miles from Spring Hill) and Kentucky's planned Toyota facility. Spring Hill lies within 500 miles of three-fourths of the U.S. domestic market. The area has a railroad, interstates, and the capacity to produce four million gallons of water daily.

Governor Lamar Alexander, who had already made Tennessee the U.S. leader in Japanese industrial investment, touted the state's "pro-business climate and its hardworking labor force" to GM. The state ranks 41st in manufacturing wages and 50th in per capita government expenditures, and it boasts a tax structure tailored for big business: a one-percent investment tax credit and no sales tax on industrial machinery, a tax exemption on finished goods, a low worker's compensation insurance rate, a low corporate income tax, no personal income tax, and a reliance on the sales tax for state revenues.

In a less than candid statement, Alexander boasted, "New York offered $1.2 billion. We didn't offer a penny." In fact, then-governor Alexander promised Saturn $50 million worth of roads, including a new I-65 exit and a connecting five-mile "Saturn Parkway" (much like that built for Nissan). Saturn will benefit from a proposed $135 million expressway loop south of Nashville. Spring Hill is getting a bypass, two stop lights, state-paid planners and engineers. Tennessee pays for water quality and regional impact studies. Saturn will receive and control $20 million worth of job training, with no requirement that Tennesseans be trained. And in 1986 the state legislature put caps on the realty transfer tax and mortgage fees that will cost the state a one-time payment of about $2.5 million and local government $75,000 each year.

Tennessee Revenue Commissioner Don Jackson predicts the state will get back $10 in tax revenues for every dollar spent on support facilities for Saturn, but Tennessee's experience with the Nissan plant in Smyrna has not borne out such optimism: the payback has been slow in coming.

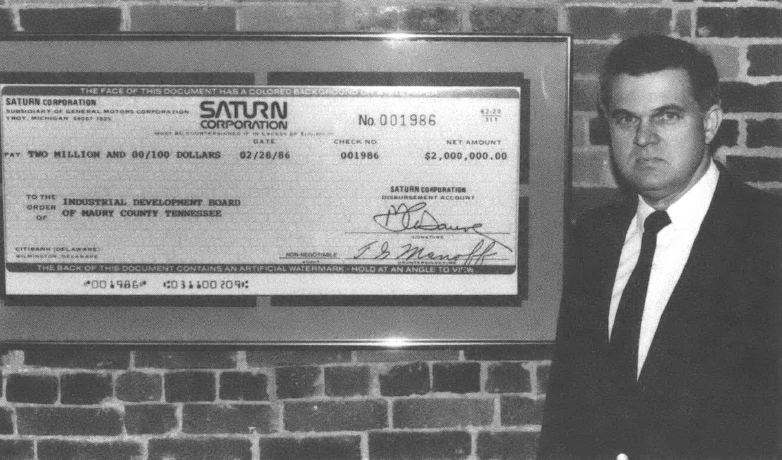

County Costs

Maury County, where Spring Hill is located, already has one of the lowest property taxes in the area. But Saturn hammered county officials into accepting an unprecedented 40-year in-lieu-of-tax agreement. The county industrial board will hold title to the site while Saturn pays $7.5 million to the county in 1986, about $3 million annually for the next 10 years, and then 25 to 40 percent of the standard property tax rate for the next 30 years. Autowatcher Ralph Nader estimates this tax break will cost Maury County almost $57 million in the first decade. Other critics put the loss as high as $100 million by 1995.

"More and more it looks like GM came to this rural area of Tennessee looking for a colony to exploit instead of a community to respect," said Nader.

"Let's be honest," said Spring Hill Mayor Jones in 1985. "We're the ones who are going to be dealing with the traffic and having our roads and our land and our homes torn apart. Nobody seems to be interested in Spring Hill."

Mayor Jones had to threaten to oppose needed zoning changes to force Saturn and the county to negotiate how much revenue the town would receive from their in-lieu-of-taxes agreement. With no commitment forthcoming, the city began the procedure to annex the Saturn site. GM then threatened to leave the county, but Mayor Jones didn't budge. Ultimately, the city agreed not to annex the plant, and county officials committed $250,000 annually to Spring Hill. Jones vows he will resume the annexation plan if the county fails to pay.

While the mayor is proud of his negotiations, he feels those between county and state officials and Saturn "were very poorly handled." He draws this analogy from his experience as a building contractor: "A lot of people underbid just to get a job. But when you've got to pay $1.25 to get a $1 job, you're taking one step backwards and it's not good business.

"It will be the people on fixed income who will suffer," says Mayor Jones. Martha Torrence, a leader of the Spring Hill Concerned Citizens Group, agrees: "We who are trying to continue here might have to move out of the area because of taxes." Two months after GM's announcement, land values had risen from $1,000 to $2,000 per acre to $5,000 to $10,000 per acre, with some acreage selling as high as $35,000.

Randy Lockridge, who farms 1,000 acres, declares that Saturn — named for the Roman god of agriculture — "will ruin farming in Spring Hill and have a negative effect in all of Maury County."

Whose jobs?

The consolation for Spring Hill's sacrifice of its traditional way of life was the promise of thousands of well-paid jobs. In September 1985, the Concerned Citizens Group began pressing GM to reserve at least 80 percent of the 6,000 Saturn jobs for area residents. But in November the group received a copy of a secret labor agreement between GM and the United Auto Workers. It revealed that "a majority of the full initial complement of operating and skilled technicians in Saturn will come from GM-UAW units throughout the United States."

In exchange for a guarantee of most of the plant's jobs, the UAW agreed to accept a wage structure below industry standards and to relax work rules, seniority rights, grievance procedures, and other provisions contained in its national contracts with GM. It's not hard to understand why the UAW signed the deal. There are some 54,000 UAW members laid off across the country, not to mention the 41,000 GM says it will lay off. Still, the unprecedented agreement has provoked a firestorm of criticism that the UAW gave up too much.

None of that matters to local officials who clearly expected jobs in return for generous tax breaks. Local employment will still increase dramatically, particularly in the service sector that accommodates the needs of the plant's work force; but the higher paying industrial jobs at Saturn seem destined for out-of-state UAW members.

One final irony: In late 1986, GM announced that the Saturn plant would be scaled back and provide about 3,000 jobs rather than 6,000.

The Bottom Line

Saturn embodies all the contradictions tied up in Southern-style industrial recruitment. Localities always hope that new plants will bring a fatter tax base, better jobs for area residents, significant community improvements, and an era of progress for the region. To secure these benefits, state and local governments take enormous financial risks and subsidize every step of a company's start-up — they build the roads, provide social and physical services, do the planning and growth management, subsidize the utilities, provide job training, waive the taxes, own the factory and land, and sometimes pay the initial wages.

In the end, the host community winds up with all the problems that have traditionally plagued the South: wages below the industry standard, tax rates so low that they harken back to the days of company towns, and a community and work force made perpetually concession-prone by the barrage of threats from their corporate "benefactor."

Lost in this vicious cycle is the key to responsible development: the same entities using the same resources could support locally generated forms of economic development which will hire local people, complement the ways of life of current residents, and build a stable local tax base and economy. As long as state officials persist in seeking the Saturns, this latter option will continue to get short shrift.

Tags

Carter Garber

Carter Garber is the coordinator of Southern Neighborhoods Network, a decade-old regional organization providing training, technical assistance, publications, and two bimonthly periodicals on community economic development and changing economic policy. (1986)

Verna Fausey

Carter Garber, Verna Fausey and Paul Elwood of Southern Neighborhoods Network wrote a longer version of this article for Southern Changes (December 1986) which is available with other materials on industrial recruiting for $5 from SNN, P.O. Box 121133, Nashville, TN 37212.

Paul Elwood

Richard Couto, Pat Sharkey, Paul Elwood, and Laura Green — all affiliated at the time with the Center for Health Services at Vanderbilt University — conducted an extensive evaluation of RCEC for the U.S. Department of Education in 1986. This article is adapted from that report. (1986)