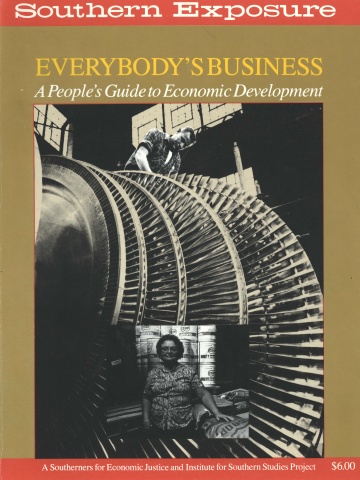

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 5/6, "Everybody's Business." Find more from that issue here.

Quick: Can you name an industry that paves its way through every county of the United States, creates employment for some 700,000 workers, and has by Congressional decree a concrete guarantee for a long and prosperous road ahead?

If you named the highway construction industry, you're right. Each year Congress appropriates billions of dollars to 50 state departments of transportation, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico in support of road building and maintenance. This money, raised in large part by the 1983 Gas Tax Amendment, reaches even the most economically depressed areas, providing welcome job opportunities from both the private and public sectors. However, despite the equal employment opportunity standards that come along with any federal money, the highway construction industry has historically offered very few opportunities to women.

In 1979 the Southeast Women's Employment Coalition (SWEC), based in Lexington, Kentucky, began investigating the hiring practices of private highway contractors and state departments of transportation. Realizing that the highway industry had a permanence that mining and manufacturing industries could never claim, SWEC Executive Director Leslie Lilly saw road work as an excellent alternative to the "pink collar ghettos" where women were traditionally underemployed and underpaid.

Across the nation, there are 1,634 miles of unfinished interstates, and 3,351 miles of secondary roads needing minor improvements. In addition, up to 80 percent of our primary road systems will need replacement within the next ten years.

Wages in the highway industry vary from area to area, but even the lowest starting salaries are usually double the minimum wage. Hourly rates for skilled workers, who often train on the job, move quickly into double digits, and overtime during summer months can make for some hefty paychecks. With its affirmative action and equal employment standards in place, highway construction looked like a perfect target industry for women trying to break the cycle of poverty in their lives.

Blatant Discrimination

SWEC's first step was to investigate the highway industry and the regulations governing it. By law, government agencies and private contractors receiving federal highway money must take affirmative action measures to hire women until they make up at least 6.9 percent of the employees in each job category. State highway departments are accountable to the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) for this goal, and private contractors receiving $50,000 or more of federal money through state contracts are accountable to the state's compliance office and ultimately to the FHWA.

Through Freedom of Information requests, the coalition obtained copies of state and private contractor reports documenting a pattern of blatant nationwide discrimination against women. Most of the equal opportunity reports filed with the FHWA listed only the total number of women workers, rather than a total for women in each job category. This meant that clerical employees "counted" toward satisfying the overall affirmative action goals. Even so, in 1980, the year of SWEC's initial research, women made up only 4.1 percent of the country's total private transportation work force. SWEC publicized these findings in a national press conference and also announced the filing of administrative complaints against the U.S. Department of Transportation and the U.S. Department of Labor's Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs for failure to enforce their own anti-discrimination regulations.

For several years, federal officials hedged on responding to the complaints, presumably hoping that SWEC would quit or disappear, along the pattern of many other advocacy organizations in the age of Reagan. Instead, SWEC has grown stronger, and since 1982 it has received a number of major grants earmarked for its efforts to improve women's access to highway construction jobs. Through this funding, SWEC has been able to create the Women's Opportunity in Road Construction (WORC) Project, and for the past three years a full-time staff has coordinated its advocacy and organizing efforts.

Under continuous pressure from the WORC Project and tradeswomen across the nation, federal officials finally began responding to SWEC's complaints and agreed to conduct investigations in a number of specifically targeted states. The results are already showing up, both on the statistical reports and on actual job sites. And although the highway industry has by no means become a major employer of women, some of the old roadblocks have been removed.

For instance, women comprised 20 percent of apprentices and 23 percent of on-the-job trainees on private construction job sites in 1984, while in 1972 only one percent of on-the-job trainees were women, and there was not even one woman apprentice in the entire nation. Despite this dramatic turnaround, women are still grossly underrepresented in most highway construction job classifications — except for clerical positions.

In 1984, women made up only three percent of truck drivers and carpenters, two percent of equipment operators, eight percent of unskilled laborers, five percent of semiskilled laborers, and one percent of supervisors and foremen. Says WORC Project Director Wendy Johnson, "It is obvious that men continue to be the primary beneficiaries of the training opportunities that lead to better paying positions." Overall, fewer than four percent of highway jobs in the skilled trades were held by women in 1984, and only an appalling one-fourth of one percent were held by minority women.

When interviewed, state transportation officials and private contractors alike moan, "We'd hire 'em if we could find 'em. But there's just not any women interested in this kind of work."

How to Get Your Foot Onto the Asphalt

Through its research and interviews with tradeswomen, Southeast Women's Employment Coalition (SWEC) has developed some practical guidelines for women seeking their first highway construction jobs.

If you want steady year-round work with regular hours, you might consider applying for a position with your state's department of transportation or its division office in or near your county. It may be listed under "transportation," "highways," or "roads and highways" in the state government section of your telephone directory. Call and find out what job openings exist and how to apply. Ask specifically about apprenticeship and on-the-job training opportunities, since many of these positions are set aside for women.

If you are told that no positions are available, wait a few weeks and call again, reiterating your interest. Employers like to hire the applicant who seems truly interested.

To land a highway construction job with a private contractor, you generally have to do a lot more legwork. These jobs do not usually show up in the classified ads. They are filled through the "good of boy" network, with job sites populated by cousins, sons, in-laws, and poker buddies. Watch your newspaper instead for announcements of highway contract awards; companies receiving large awards are likely to need more employees and may be required to hire a specific number of women.

Call your department of transportation and ask to speak to a contract compliance officer. Find out if any companies are seeking women applicants to satisfy conciliatory agreements.

If you have any friends or relatives working for highway construction companies, ask them to let you know when openings occur. Employers still prefer hiring through the "good of boy" network, even when the person hired is a "good of girl."

Many construction jobs, especially on large projects, are union jobs. Contact the union local for the craft you're interested in and find out how to join. Be aware, however, that unions fill jobs based on seniority, and it may be hard for a newcomer to "break in."

Talk to workers on job sites, asking about other construction work in the area. Drivers of trucks, taxis, and "chuck wagons" are also good sources of information about construction jobs.

When you go the job site, go early in the morning and be dressed for work. Take a hard hat (purchased at an industrial supply outlet) and your lunch since the foreman may hire you on the spot. Wear jeans or overalls, boots, and work shirts. Pin up long hair. Do not wear dangling earrings or bracelets; besides being inappropriate, jewelry can be hazardous around equipment.

Whenever possible, two or three women should go job hunting together. It is important to document what you are told when seeking jobs in order to support a possible discrimination complaint. If you are told the company is not hiring, ask when it will be hiring. If you are told to sign up at the union hall, be sure to do so and request that the contractor call the hall and ask for you. Ask about other locations at which the contractor may have work.

If you are told to come back on Monday, go back. Very few people are hired the first time. Even if you were not told to return, do so anyway to demonstrate your interest and determination. In addition, you can find out if new apprentices or employees have been hired since your last visit. If they have, ask why you weren't hired.

Once, when challenged to back up its claim that women were indeed interested in nontraditional work, SWEC placed a classified advertisement in the local newspaper. Dozens of women responded within days, saying, "Yes! I'd love to do this kind of work. Where do I apply?" Some said they "never knew women were allowed" to do highway construction. Most were employed in dead-end, low-paying jobs such as waitress, nurse's aide, factory worker, or secretary. They all saw highway work as offering them potential to develop valuable skills and earn a living wage. SWEC set up several informational meetings with the women who came out of the proverbial woodwork to respond to the advertisement. Referrals were made and a number of women began their job searches with confidence and an understanding of equal opportunity law.

One of the primary goals of the WORC Project has been the identification and organization of support groups for current and aspiring tradeswomen. WORC offers technical assistance to women and groups all over the country, educating them on equal employment regulations and encouraging creation of local strategies. As an organization, SWEC has always had a commitment to the development of grassroots leadership, and the WORC Project has been a key vehicle for achieving that goal.

Bittersweet Testimony

With the opportunity to come in contact with so many women in or interested in the trades, the WORC Project is collecting narratives of their experiences, good and bad, on and off the job. Johnson and WORC National Organizer Suzanne Feliciano encourages any interested women to contact them to share "evidence."

One piece of telling information generally attained during interviews with women who have been hired into construction jobs is that they know they were hired because the company "needed" them. "My brother said they wanted to hire a woman," says one laborer of the company that hired her. "I'd heard they needed a black woman," says a truck driver of two years. "So I went down and talked to the foreman and he hired me."

This is bittersweet news to WORC staff — good in that it is proof the rules are being enforced, bad since it implies contractors are only hiring women because they have to, not because they believe women can do the job.

Susan Jones of Sharpsburg, Kentucky has been working as a carpenter trainee for two years. Her company is involved in a conciliatory agreement that requires it to hire one woman for every five male employees. Once employed by a nursing home, Jones "decided I could use more money" and applied for her current position on advice of her boyfriend, also a construction worker. And is she making more money? "Oh, yes!" exclaims Jones, a single mother of two children.

Jones's experience on the job site has generally been positive. Although her first day was "scary," she quickly found the "job was a lot easier and the men were a lot friendlier" than she had expected. She eventually had problems with one co-worker, who resented her presence and called her a "black whore" in anger one day. Jones, who considers herself thick-skinned, was at first so deeply wounded by the remark that she felt she couldn't go back to work. Instead she took her grievance to the company's Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) officer, who told the offending employee that his language had no place on the job and that his job depended on it changing. Jones had no problems again.

Her testimony is a good indication that the system can do what it's supposed to do, but WORC Project investigation shows that discrimination — both on the basis of race and sex — is still rampant in the industry. In the comfortable embrace of Reagan's second term, U.S. Department of Transportation officials have once again begun ignoring SWEC's demands for action. Results of the promised investigations have never materialized. Says Johnson candidly, "We haven't heard anything from those jokers since December (of 1985). It's obvious that women's issues rank low on their list of priorities." Despite this slight, the WORC Project will continue to keep the Transportation Department high on its list. It plans to focus attention on the department's recalcitrance during congressional hearings in February, and it is considering additional legal and public education strategies to pressure state and federal agencies to live up to the law.

Meanwhile, the project has prepared a manual for women and groups seeking to break into construction. The manual, titled "Job Development in Highway Construction: A Road Map for Women and Advocates," offers detailed information and practical guidance on the structure of the federal-aid highway program as well as tips on the hiring process, particularly as it applies to women.

Some of the roadblocks are coming down, but a lot more must be removed before women truly have an equal opportunity to all the jobs in the highway construction industry. Next time you find yourself approaching the familiar orange sign warning you of "Men at Work" ahead, just take a deep breath, cross your fingers, scrutinize the crew closely, and thank the WORC Project if it isn't true.

My Turn: Closer to Home

The federal government must increase the minimum wage for all workers in the United States. Today the head of a family of three persons earning the federal minimum wage and working full-time lives $1,300 below the threshold of poverty. The current minimum wage is a subminimum wage. A fair change could remove as many as four and one-half million people from poverty and would require no additional administrative costs to the government. This is a vital anti-poverty measure that could do more than any other single, simple act to reduce poverty.

— Steve Suitts, Georgia

Tags

Glenda Conway

Glenda Conway, a former staffmember of SWEC, is a freelance writer and college English instructor in Kentucky. The manual, "Job Development in Highway Construction: A Road Map for Women and Advocates," is available from SWEC at 382 Longview Drive, Lexington, Kentucky 40503. (1986)