When the Government Said, “Let’s Put On a Play”

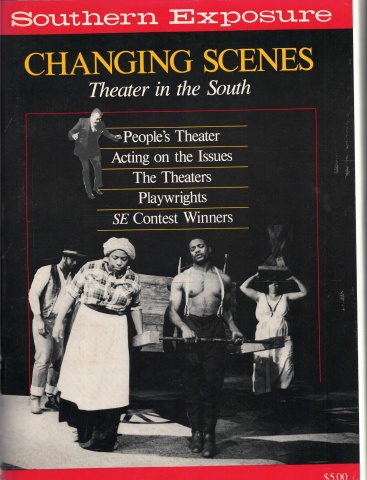

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 3/4, "Changing Scenes: Theater in the South." Find more from that issue here.

It is President's Day, June 10, 1936, and 40,000 Arkansans have gathered to welcome Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt to Little Rock. In the city 's giant amphitheater, the Roosevelts view the work of the local Federal Theatre unit, America Sings!, a moving historical pageant, a life and times of the state of Arkansas.

Through song and story the sweeping spectacle takes its audience through time from the retreat of lndians before the land-lusting pioneer, the development of the plantation system and slave culture, the devastation of Civil War and Reconstruction, the clash of agriculture and industry, the call to the first World War and, finally, the crash of 1929.

That pageant typifies, in many respects, the Southern response to the controversial Federal Theatre Project (1936-39), one of the more creative expressions of Roosevelt's far-reaching New Deal. During its brief tenure, the project put thousands of theater professionals back to work, giving them new hope and the dignity of working for their dole. Significantly, it was America's first substantial if ill-fated experiment in subsidizing the arts.

Such pageants — along with children's theater, folk plays, rural drama, marionette productions, and the vaudeville — most visibly characterized the Federal Theatre' involvement in the South. The project's Southern legacy can be seen in developments as diverse as the prolific pen of playwright Paul Green, Tampa's unique Spanish Theatre, and the lively community theaters of Carolina.

Theater in the South "developed slowly" compared to other regions, recounted the project's national director Hallie Flanagan in her memoirs. It barely got on its feet before cutbacks in appropriations from the project' parent agency, the Works Progress Administration, shut down all but most productive theater units. By 1937 many of the South's units had been slashed altogether, hurt by the lack of local WPA support or by the units' failure to attract community interest.

In 1936 relatively few theater professionals had signed up for relief in South, a prerequisite for employment in the project. From Washington's perspective, this should have nixed most Southern involvement in the project from the onset. The Federal Theatre Project and the WPA, which coordinated the nation's vast relief effort, generally were designed to serve strictly as relief and employment enterprises. At the project's closing in 1939 Senator Josiah W. Bailey declared, "The object of the WPA is relieve distress and prevent suffering by providing work. The purpose is not the culture of the population."

But Flanagan had other visions — visions that often conflicted with official WPA policy but whose outcomes were almost always positive. She intended to make the Federal Theatre a critical success, to put the project at the forefront of theatrical achievement and experimentation. She also dreamed of exploring and developing the dramatic material of all of America's indigenous regions. To some extent, Flanagan's dreams foreshadowed the regional theater movement which dominates the American stage today.

Flanagan, with her boss and former Grinell College classmate WPA Administrator Harry Hopkins, envisioned the blossoming of what he called "free, adult, uncensored theater." As other New Deal programs and social activists aimed to bring about political and economic democracy, some artistic intellectuals hoped that this theater project would nurture a new cultural democracy, introducing the stage and working people to one another. Flanagan had directed Vassar College's Experimental Theatre and had been the first woman awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to study European and Russian theater, and she encouraged plays with a "vital connection" to the immediate problems of people in the audience. At its high point the Federal Theatre Project entertained a weekly audience of 350,000, often bringing free entertainment to recreation centers, settlement houses, and hospitals, among other places.

As Flanagan saw it, the Federal Theatre would be less a national theater than a network of autonomous regional theaters; these groups would not only bring art to traditionally underserved communities but would also interpret and record the culture and fabric of the American landscape itself, enriching the lives of its people.

In the South Flanagan saw "rich dramatic material in the variety of peoples, the historical development, the contrasts between a rural civilization and a growing industrialization, such material practically untouched dramatically."

With a few notable exceptions, however, that material would remain untouched. Southern participation in the Federal Theatre Project was, on the whole, a limited undertaking relative to that in other regions. Indeed the South's experience with the Federal Theatre experiment is significant as much as for what it did not produce as for its achievement.

Ironically, the plays which did treat Southern issues and which might have enlightened its people were rarely produced in the region. Detroit factory workers evidently gained more from Paul Green's Let Freedom Ring, when it was produced in that city, than the Carolina mill workers it dramatized, for the play was never produced in the South. Turpentine, by J.A. Smith and Peter Morell, a play about the tyrannical conditions of the Southern labor camp system, was not staged in the region. Nevertheless it produced no small ire below the Mason-Dixon Line. In the play, produced by the Harlem Negro Unit, black workers in a Florida turpentine camp rise up against the white bosses who have practiced economic and sexual exploitation against them and their families. Savannah's weekly Naval Stores Review and Journal of Trade called the play a "malicious libel on the naval stores of the South" when it played New York in 1936.

Nationally, the often controversial "Living Newspapers," would emerge as the Federal Theatre's hallmark. This dramatic medium, reminiscent of the agitational-propaganda ("agitprop") theater of Russia and Germany in the 1920s, took the form of a newspaper, exploring all sides of the day's important social and economic issues. A script would introduce a social problem and then call for its solution. The project spawned a dozen or so Living Newspaper scripts which were produced and reproduced in theaters throughout the country, each unit incorporating local geography and circumstances into the production.

Such Living Newspaper productions as Power, which called for public ownership of utilities; Triple-A Plowed Under, a play about the crisis in agriculture; and Spirochete, a look at the threat of syphilis, raised the eyebrows of those who interpreted the medium's inherent questioning of the status quo as communistic.

Despite their national popularity, Federal Theatre records show that only one Living Newspaper, One Third of a Nation, was produced in the South, by the progressive New Orleans unit. The play — inspired by Roosevelt's famous statement, "I see one-third of a nation ill-housed, illclad, ill-nourished" — exposed the deplorable housing conditions of cities. In New Orleans the play was adapted to explore housing conditions there.

Nationally, the Federal Theatre Project spearheaded the growth of black participation in the theater. While blacks and whites primarily participated in separate Federal Theatre units, the project introduced a few mixed-cast productions amidst some controversy. And for the first time, blacks in the pioneering Negro units outside the South were given the chance to develop their skills at directing and playwriting. Despite its temporary nature, the position of blacks in the theater improved under federal auspices. These units also resisted traditional "bandanna and burnt-cork casting" (which relegated blacks to stereotyped roles), choosing instead to adapt classics reinterpreted through black culture with all-black casts (Voodoo Macbeth in New York, Swing Mikado in Chicago).

Black theater units thrived in urban centers outside the South such as Chicago, Seattle, New York, and Boston, producing material which took a first, cautionary glance at the experience of blacks in America's history. But in spite of the significance of such "problem plays" as Walk Together Chillun, Turpentine, and Sweet Land — plays that began to explore seriously the Southern black experience — they were not viewed on Southern soil. Clearly the South of the late 1930s was unready or unwilling to take such a critical look at itself. Instead, the few black theater personnel in the region concentrated on the traditional black media — minstrel shows and musical reviews.

But this is not to diminish the significance of the Federal Theatre Project in the South. In rural areas where many had never seen a performance of any kind, the value of the project was immeasurable. What Flanagan reported of the project's national reception in Federal Theatre Magazine in 1936 was especially true for the South: "The great majority of our performances are given to audiences which rarely have an opportunity to see theatrical entertainment with living actors. These include CCC [Civilian Conservation Corps] camps and state institutions, and audiences in small cities and rural communities, granges, etc. many of which have no regular entertainment except what they devise for themselves, and most had not, until Federal Theatre came, seen a play with living actors for five or ten years."

In the South's cities, the projects played in existing theaters, charging a nominal admission to the mostly middle-class audiences that attended. Sometimes the productions revived theaters that had been closed, and they often gave new vitality to community theater groups.

The shape that Federal Theatre projects took in the South, as in other regions, depended on the availability of out-of-work theater veterans and the kinds of skills they brought to the project; the attitudes of local WPA administrators, the vast bureaucracy that oversaw the theater and other arts projects with wildly varying degrees of sensitivity and aptitude; and the quality of resources that already existed within communities.

The Atlanta unit came closest to hitting the South where it lived. It did so with Altars of Steel, a play by Alabamian Thomas Hall-Rodgers that explored the rise of the steel industry and the South's new political economy. The play depicted the giant "steel " absorbing the independent mill owner of the South, and raised the sensitive issue of absentee ownership.

Striking so close to home, Altars of Steel drew both darts and laurels. Flanagan herself assessed it as the Federal Theatre Project's "most successful play " in the South because it was "the one written for and about the South. . . . Audiences crowded the theater for Altars of Steel. They praised the play. They blamed the play. They fought over the play. They wrote to the papers: 'Dangerous propaganda!' or 'Dangerous! Bah! If this is propaganda it is anti-communistic! Those who like their plays limited to lilacs, lavender, and old lace, moonlight and roses, pale perfumes or circus lemonade — stay away!'"

The Atlanta Constitution understood the significance of a local production of a play grappling with pertinent regional issues. It bragged that Altars was "as great a play as was ever written. It is as daring as anything the stage has seen. It is superbly produced, perfectly acted and it is not in New York, London or Leningrad. It is here in Atlanta at the Atlanta Theatre."

Such controversy was inevitable. In the play, the forces of communism, capitalism, and liberalism are pitted against one another, but none of the political philosophies clearly triumphs. For example, the capitalist mill owner relaxes safety standards in his mill, causing an explosion which kills 19 men. Although the workers riot, a Communist union organizer, generally depicted as irrational and frenetic, fails to gain their support and eventually is shot by a National Guardsman.

The play also treaded on a regional soft spot: the industrialization of the traditionally agricultural South. It galvanized the community to take note of the project's activity and generated important, if sometimes negative public comment. According to Gilbert Maxwell, an actor on the project, "The main trouble with Atlanta was it did not support the theater. [With Altars] we turned them away night after night. We expected controversy, but we also thought it would draw enormous crowds . . . we did draw enormous crowds."

Besides taking on political and economic issues, the play was significant for breaking new artistic ground as well as demonstrating that striking but low-cost productions could be created. The stipulation that 80 percent of Federal Theatre money be used for salaries mandated low production costs. Josef Lentz's ingenious stage design — the entire play takes place atop a giant cog, literally representing steel shafts as well as the giant threat of steel — attracted national attention.

In some rural Southern areas, the Federal Theatre created programs of community drama. According to Flanagan, "The object was not to put on plays but to get plays out of the people themselves." The residents responded, wrote Flanagan, with their own folk art: storytelling, folk songs, and dance. Children were encouraged to make puppets and create dramas for them. Older people told tales from their own youth.

In bringing together theater professionals and audiences who had never seen theater, the Federal Theatre Project fostered a remarkable cultural interchange. Herbert Price, who directed rural community drama in the Southern region, was dismayed by rural poverty but was galvanized to act. He wrote of Federal Theatre audiences in what he called the "black ankle belt " because "their feet are still in mud." "They live in indescribable want, want of food, want of houses, want of any kind of life. . . . Their only entertainment is an occasional revival meeting, so when I get excited, tear around and gesticulate, they think it's the Holy Ghost descending upon me. It isn't. It's a combination of rage that such conditions should exist in our country, and chiggers [pesky, skin-burrowing insects], which I share with my audience."

For their part, audiences opened up under the new experience of participating in theater. When Price later brought theatrical entertainment to flood victims in Tennessee, he reported, "The refugees were completely carried away. The children loved our show. The mothers and fathers showed their appreciation by joining in a community sing when our program closed. One picture that remains is that of a mother nursing a baby at her breast, entirely lost to everything but the performance."

In addition to bringing theater to new audiences, the federal project strengthened and amplified existing theater. In North Carolina the Federal Theatre took up residence at the University of North Carolina under the direction of Frederick Koch, who as director of the innovative Carolina Playmakers there had developed a system of strong community theaters throughout the state. By plugging into this ready-made structure and working with 18 of these groups, the project was able to improve production standards and to build a base of community support in a state with few professional theaters.

In July 1937 the North Carolina project also spawned the historical outdoor drama, The Lost Colony, performed in coastal Manteo in a new theater built by the Works Progress Administration. Paul Green's now well-known drama was performed 75 times during the project's tenure and continues to this day to tell the story of the first English settlement on Roanoke Island. [see article, p. 37]

Through the Federal Theatre, Paul Green took his stories of the South to communities all over the country.

Louisiana's New Orleans unit, like the one in North Carolina, benefitted initially from the existence of an established theater structure, the Le Petit Theatre du Vieux Carre. This troupe was recognized as one of the more serious and daring of the Southern dramatic units. In 1938 this unit produced the single Southern production of a Living Newspaper.

The Federal Theatre's obligations extended to helping the fading vaudevillian, minstrel, and marionette workers in New Orleans and throughout the South. These stage veterans had suffered a dual blow. Besides finding themselves out of work, they also found themselves artistically out of step as the long-established vaudeville circuit disappeared. But under federal guidance, these performers briefly toured once again, visiting schools and other institutions in Louisiana and providing welcome entertainment and a needed community service. In New Orleans Flanagan encountered Hermann the Magician, "an elderly gentleman whose formal morning coat was covered with medals." He told her, "I have played before audiences all over the world and have received decorations from royalty, but I have never enjoyed audiences as much as these . . . crowds."

In Florida the Federal Theatre Project established a dynamic Spanish-Cuban unit in Tampa, accommodating the city's large Hispanic population. It was the only Spanishspeaking federal troupe and produced Spanish operettas, musicals, and dance. The unit also restored the luxurious Rialto Theater, built in the 1920s to showcase Spanish stars.

Here and in other major Southern cities, revenues from in-town productions allowed companies to take road shows — classics and musicals — to outlying high schools and into remote areas to the rural poor.

Audiences' unfamiliarity with live performances was evident. Flanagan — who often visited productions — reported from a little community called Watchula, "We played musical comedy and no one laughed. The director went out and said 'What's the matter? Why don't you like it? Why don't you laugh? Why don't you clap?' An old lady said, 'We'd like to laugh but we're afraid to interrupt the living actors. It don't seem polite. We'd like to clap, but we don't know when. We don't at the pictures.'" In another Florida hamlet Flanagan saw "an old man barefoot, helping children from an oxcart, [who] said, 'They may be pretty young to understand it, but I want they should all be able to say they've seen Shakespeare — I did once, when I was a kid.'"

In Texas the Federal Theatre established the successful Dallas Tent Show Theater, which made use of the state's large contingent of out-of-work tent-show and circus performers. Its "playhouse on wheels" traveled to playgrounds, parks, and CCC camps, offering variety and marionette shows. Similarly, units in Dallas and Fort Worth took one-act plays and marionette productions to schools and parks. But by mid-1937 lack of local support and tightening federal funds had closed the unit.

In time, the entire Federal Theatre suffered the same fate. Federal Theatre veteran and now well-known actor John Houseman later wrote, "As the Great Depression lifted and the economy began to pick up under the stimulus of an approaching war, the Federal Arts projects became superfluous and politically embarassing. The Federal Theatre was liquidated, buried, and largely forgotten in the new excitement of World War II."

Politics played no small part in the project's demise. The Texas units, for example, had suffered from a conservative state WPA administration which resisted all but the most innocuous plays. Flanagan recounted the words of one administrator: "Do old plays. We don't want to get into the papers. Do the old plays that people will take for granted and not notice.''

Between 1938 and 1939 the Federal Theatre became the subject of congressional investigations on un-American activity. The anti-red attack was taken up by politicians who opposed New Deal programs in general, and who saw the arts in particular as an inappropriate arena for the American government. The controversial Living Newspapers and the project's association with radical theater unions made it a convenient scapegoat for the House Special Committee on UnAmerican Activities, led by Texan Martin Dies, who claimed the project was infiltrated by Communists. The little evidence the committee uncovered was flimsy and largely erroneous, but extremely damaging anyway. Fearing that its Congressional appropriations were a risk, the WPA sat quietly while the Federal Theatre came under fire from Congress. The agency failed to defend the project's record and hoped that a single sacrifice would satisfy opponents of the overall relief effort. The fight against the project in Congress was led by Clifton A. Woodrum, chair of the House Committee on Appropriations, whose declared aim was to "get Uncle Sam out of show business.'' Despite a valiant lastminute effort by Flanagan, with support from leading stage personalities and theater critics, the project was voted out of existence on June 30, 1939, by an act of Congress.

The Federal Theatre's impact, however, cannot be denied. True, in the rural South, with its few professional theaters or actors, the project was clearly less experimental than in other regions, and its few serious dramatists were more isolated and rarely received the acclaim affored those in the nation's major arts centers.

But if they lacked critical success the Southern theater units were certainly a human success, bringing art to people who had never before experienced it, revitalizing spiritually depressed communities and restoring the dignity of hard-working theater professionals. While it failed to probe seriously the cultural forces that drove and perhaps hindered the South, the Federal Theater took on a form in the region that surely reflected existing Southern culture and conservatism and took an important step toward realizing Hallie Flanagan's grand vision.

Tags

Beth Howard

Beth Howard, a native of North Carolina, is a writer and editor now living in Washington, D.C. (1986)