Staging a Good Time

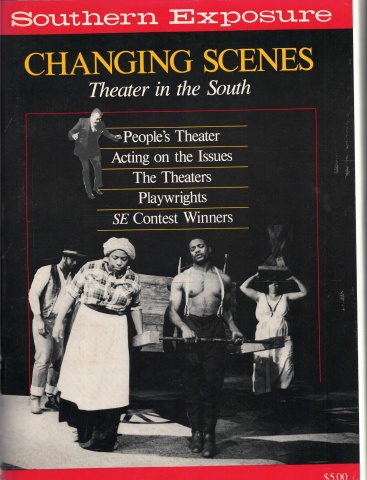

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 3/4, "Changing Scenes: Theater in the South." Find more from that issue here.

When we think of the word “theater,” the first image that comes to most people is probably that of a building; second, a stage; then of actors, costumes, scripts, lighting, on down the line to critics’ reviews. Yet in the South, in particular, because of the relative smallness and isolation of its communities, theater has been, and in many ways still is, a generic term that encompasses a multitude of performing arts.

In that sense, theater predates the British colonization of this region, this country. Most Native American tribes used pageantry in elaborate rituals to pay homage to nature and the change of seasons, to celebrate marriage and birth, to pass the spirits of the dead from this world to the next.

With the arrival of the colonists, the Native Americans brought their pageants to treaty negotiations, complete with costumes, music, and dance. They used pantomime to teach the colonists about the planting, harvesting, and preparation of native foods.

As in every culture since humans learned to communicate through words and images, storytelling —religious, tribal, or family-based — was a fundamental way for generations to pass on history and information as well as to entertain.

As the colonists moved west to the Appalachian region, storytelling was combined with traditional Scotch-Irish music into folk songs. They were tales of love as in “Wagoner’s Lad,” of death as in “Railroad Boy,” or of the faithfulness of a dog as in “Old Blue.”

“Ye Bare and Ye Cub” — “bare” meaning bear — was the first documented scripted theatrical performance in the country, dating to 1665. Unfortunately, in that era “the theater” was considered immoral and actors degenerates. The two Virginia men who attempted to perform “Ye Bare” were arrested on the spot.

Charleston’s Dock Street Theater — the South’s oldest and still operating today — opened in 1736, but another generation would pass before theater, proper, would be accepted, and professional companies and houses were established in Northern cities in the 1770s and ’80s.

The South was not devoid of theatrical entertainment outside of Charleston before then, however. Medicine shows may have been the first advertising use of musical and theatrical performances — the hawking of patent medicines. And circuit-riding preachers often enthralled audiences with stories, songs and news from other towns they had visited.

On the old plantations, slaves served as a source of entertainment as well as labor. Their night-time songs and dances drew the attention of the slaveholders, their families and friends, who found the slaves’ energetic performances far superior to anything they could find in town. By the 1840s white entertainers adopted elements of the slave “shows,” painted their faces black, and took to the Northern stages as minstrels. It was one of the first — but certainly not the last — example of white Americans exploiting black culture.

During the same period, circuses began to flourish in the South. The earliest recorded American circuses in the early 1700s offered the public little more than a glimpse at a few thenexotic animals — a camel, a lion, a bear. Over the next century, acrobats, equestrians, “wild” animal trainers, and of course minstrels were added to the shows, and the South — New Orleans, in particular — became a winter haven for the troupes.

“Floating circuses” on the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers became the rage in the mid-1800s. Entire

shows were housed and performed on huge boats. Although showboats were expensive to build, by using cheaper water routes they reduced the cost and effort of transporting the animals, performers, tents, and sets from city to city. One of the largest and most popular, the “Floating Palace,” seated 1,800 people in a gas-lit, heated, and sumptuously furnished gallery overlooking a regulation circus ring and stage.

Circuses, like most other forms of mass entertainment, came to a standstill during the Civil War. Decades passed before the South recovered economically and socially to the point that theater once again encompassed the “proper” as well as the folk performing arts.

Today, the variety of theater in the South is surely comparable to any other region of the country. Major theatrical production companies stretch from Atlanta to New Orleans and from Louisville to Richmond, and almost every mid-sized town has its own community theater. Scattered throughout the region are mimes, jugglers, puppeteers, and of course drawling storytellers who delight audiences from the smallest hamlets to the urban arts centers. And, as reflected throughout this issue, the South has an enthusiastic, talented and growing corps of performing artists and theater companies that are tapping the region’s distinct culture, history, and politics for unique and innovative productions.

Most of these artists are struggling, as artists always have. But at least they don’t have to worry about getting arrested for practicing their craft like the two Virginia performers were in 1665.

Tags

Rebecca Ranson

Rebecca Ranson is a playwright who is a native of North Carolina. The author of over 30 plays produced in many cities across the country, Ranson bases most of her work on voices of the oppressed. (1986)