A Letter to Workers' Art Groups

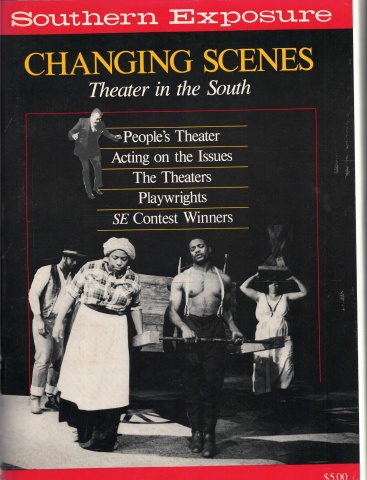

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 3/4, "Changing Scenes: Theater in the South." Find more from that issue here.

Although many of the grassroots theaters profiled in this issue were born in the 1960s, the idea of people's drama had surfaced in the 1920s, too. Radical intellectuals then had turned their attention to creating and using popular art forms to capture the imagination of workers and to organize them. In the September 1929 issue of the progressive magazine New Masses, editor Michael Gold sounded this appeal to workers' art groups, hoping to unify them into a national league:

Under the surface, in capitalist America, there is quietly growing a Workers' Art movement.

It has no manifestoes, it is not based on theories, it springs from life itself.

It fulfills a need; it has grown out of necessity. It is as much a part of revolutionary history-in-the-making as [the Communist-led] Gastonia [textile strike] or the [Communist Party] Daily Worker.

There are at least 50 small workers' theater groups functioning in American cities and towns.

There are over a hundred workers' cinema clubs which produce, in little halls and clubrooms in industrial towns, programs of novel moving pictures with their own cooperative projection machines.

There are at least 25 workers' choral societies meeting several times a week, some of them numbering, like the Freiheit Chorus of New York, a total of 600 members.

I have tried to figure it out; and my conservative conclusion is that 50,000 revolutionary workers in America are connected with some local group for the discovery and practice of Workers' Art.

I know that the bourgeois intellectuals sneer at this spontaneous urge toward workers' culture, and obstruct it wherever they can.

Every week in the office of the New Masses, we receive at least a dozen letters asking us to suggest suitable oneact workers' plays, short movies, recitations and choral pieces.

We have been unable to satisfy this demand. The reason is that the field has not been organized. It is a commentary on the situation that the most popular piece that was printed in the New Masses during three years was the oneact play by Harbor Allen, named Mr. God Is Not In. This play has been presented at least 20 times since its printing.

It is time this work were organized. It is valuable work. It is a way of reaching the youth of America. It is a way of reaching the workers in places where pamphlets and speakers do not penetrate.

It is a way of capturing the mind of hundreds of thousands of workers in a simple, natural way.

The bourgeois little theater movement is already a national force; here we have another, ready to our hand.

One need not wait until the official leaders see the necessity of such organization. They will not do so for a long time.

Let us organize now, despite the novelty of it all. Let every group engaged in workers' cultural activities take this first step:

Send in a brief report of your membership, your recent activities, and your future needs to the New Masses.

We think we can help. It is possible we can form a national league to join up with the world organization of workers' art.

We may be able to work out a repertoire of workers' movies. We may be able, if there is enough support, to publish the much-needed book of workers' one-act plays.

There are many other jobs to be done. The first step is for the secretary or most active member in each group to write us a full report. We will be glad to give regularly one or two pages of the magazine to such reports, and to begin planning a national program for the future.

Let us hear from you. Even if there is no group, write us your views as an individual. No theorizing, etc.; we want concrete, practical ideas for work. This is a big thing; Germany has a workers' theater society with a membership of a half-million. Something less gigantic but as useful is possible here. But everyone must write us at once. Let us see first where we stand.

In the months that followed dozens of worker groups responded, especially theater companies. New Masses regularly set aside a page or two for these letters, which came from as far as England as well as from theater groups and workers' clubs in America.