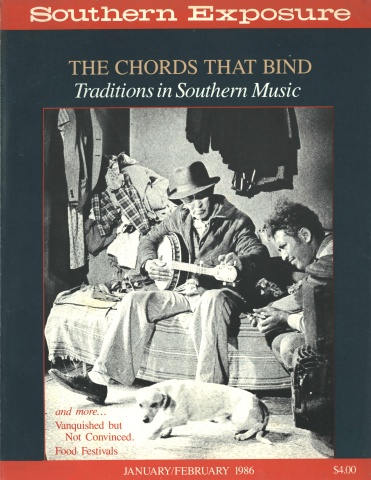

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 1, "The Chords That Bind." Find more from that issue here.

In researching "Food Festivals," the authors logged over 75,000 miles by car, bus, plane, and boat. In addition, they have the world's largest collection of food festival T-shirts.

While smacking our lips at our favorite annual chicken barbecue — given by the Cutchogue (New York) Fire Department — we realized that there must be thousands of local food celebrations and festivals all over the country. Many of these festivals have gained nationwide recognition, and tickets for some have to be ordered as much as a year in advance. Food festivals combine the excitement of a celebration with the fresh taste of local foods and the honesty of homemade preparations. In an era of potato flakes and imitation bacon bits, it's comforting to have the real thing.

We admit a certain bias toward festivals that have a small-town character, those that close down the town for the weekend or that involve all the schoolchildren in painting shop windows and making posters. We think that festivals are most fun when the music gets people moving, the parades bring cheers from the sidelines, and the cooking contests make local heroes of housewives.

Most food festivals are stand-up affairs, where you go from booth to booth and sample different foods using the same ingredient (as at the Garlic Festival) or different preparations of the same food (as at the Boudin Festival). Some festivals have sit-down meals in addition to the booths (as at the Maine Egg Festival), and a few are in themselves a meal (notably the dinner at the Shaker Kitchen Festival and the Bradford Wild Game Supper). Some are all-you-can-eat affairs (the Chincoteague Oyster Festival), but most are pay-as-you-go. Food varies from booth to booth, but somehow the crowd always knows: Head for the booths with the longest lines or biggest crowds, for they will usually have the best food.

Festivals range in length from one day to two weeks. We have never spent more than two days at a festival, but there are families who come for the weekend or whole week. It's not unusual to see a section of the park or fairgrounds set aside for campers. Festivals are ideal entertainment for everyone. There's almost always something special going on for children, but there are also events and activities for retired people, locals, tourists, singles, and teenagers. Many festivals have a midway, often set off to the side. Almost all have at least one stage, for concerts, contests, and award ceremonies. Starting in the 1970s many festivals added a foot race; some of these are officially sanctioned but all attract an astonishing number of runners. Some festivals are agricultural fairs, and have judgings for the best-looking livestock or produce. Often festivals include competitions that mean a great deal to the people in the region, like the ox pull at the Maine Egg Festival or the garlic topping in Gilroy, California. A great many have eating contests, races against time that are usually a little embarrassing but always a lot of fun. Other festivals have zany events like bed races or crazy costumes. We've also seen our share of tractor pulls, mud hops, and tug-of-wars. Most festivals have beauty pageants; after all, what kind of a festival would it be without a queen to kiss winners, award trophies, and generally assure that everyone has a good time?

Flea markets and crafts booths are standard features at festivals, and they vary in quality. Sometimes sales stands offer a chance to buy a unique country-made item, but more often than not the things for sale are from commercial kits or are so similar that they appear to be. We've also noticed that antique cars, old fire engines, and early farm equipment are big stuff. The parades are frequently a chance to sport these items, along with huge pieces of modern agricultural equipment, combines and tractors. These are usually interspersed with high school marching bands, waving politicians, floats, and beauty queens in Corvette convertibles.

What you can expect from an hour or a day at a festival depends on your interests. Some festivals zero in on a local specialty. Some, such as LaBelles's Swamp Cabbage Festival in Florida, call attention to a food that remains unknown to most of the country. Many festivals celebrate a particular raw ingredient — apples or rice or pecans — while others involve a prepared item such as Louisiana's boudin (a sausage), or North Carolina's barbecue (chopped pork in a vinegar-based sauce).

Food festivals are fun. They celebrate harvests and bounty. They are America letting loose for a party.

World Catfish Festival

Belzoni, Mississippi

Barking fish, mud puppies, bullheads, whisker faces — regardless of their local names — catfish are caught and eaten in many parts of the United States. In Mississippi and other delta states, they are also farmed. And in Humphreys County, Mississippi — the self-proclaimed catfish capital of the world — over 22,000 acres of ponds produce millions of pounds of fish each year. The state's governor declares in his annual proclamation, "There is no greater delicacy than Mississippi farm-raised catfish . . .," and goes on to declare the first week in April as Mississippi Farm-Raised Catfish Week. The highlight of this week is the annual catfish festival hosted by the town of Belzoni, the county seat.

On a sunny April day we drove north from Jackson (75 miles) across flat, often flooded countryside. Small houses and farms were set back off the road; flowering trees graced side yards. We drove through towns called Yazoo City, Craig, Louise, Midnight, and Silver City, heading for a celebration of the fish that Craig Claiborne has described as "the finest freshwater fish in America, including pike and carp." Over 20,000 people come to Belzoni for the festival, and though many are involved in the catfish-farming industry, others come because they like catfish, especially this farm-raised variety.

The courthouse lawn was the focal point for the festival. In the pond in front, kids angled for wooden toy catfish. The streets were turned into a bazaar. The 10,000-meter Catfish Classic had been run at 8:30 that morning, and runners were still milling around with their numbers pinned to their chests. Crowds were gathering all morning — bus tours from Jackson, families in station wagons and pickups. A school bus stopped near the festival center to take passengers on a tour of the catfish ponds and factories. While the runners received their awards, others were buying their tickets for the catfish dinner. On the side lawn a crowd gathered around a man playing the glass harp, and in front of the courthouse Minnie Simpson's School of Dance was presenting the "Catfish Follies."

Behind the courthouse, we marveled at the quantity of food being prepared for the dinner. Catfish fillets by what seemed like the ton were being dusted with cornmeal and dipped into hot fat until they were crispy deep-fried curls. Balls of cornmeal dough were also deep-fried into crunchy, almost greaseless hush puppies. The midday catfish dinner was being served, and people passed along the food route to pick up their platters of catfish, hush puppies, cole slaw, and Coke. They ate at long standup tables and as they dispensed the obligatory ketchup onto their catfish fillets, they discussed the festival, the catfish, and the weather.

Is farm-raised catfish better than river catfish? There's no question that raising catfish in manmade ponds and feeding them grain removes some of the uncertainty of eating catfish. Many kinds of catfish are scavengers, and they eat whatever is along the bottom. Nicknames such as mud puppies and mud cats tell the story: Caught catfish is often tough, fishy, and gritty or muddy-tasting. The catfish at Belzoni are developed from a variety of channel catfish — a predator, not a scavenger — and are fed a steady diet of grains to develop a sweet flavor. They are harvested at optimum sizes and quick-processed, often frozen, then shipped to over thirty-five states. The people at our lunch table said they felt the farm-raised fish were fresher and had a pleasanter taste. They are also easier to cook, since they come to market already skinned. (Catfish are difficult to skin because of the barbs along their sides and because the skin adheres very tightly to the flesh.)

The flesh is moist and delicate, and the fish lends itself to a variety of preparations. For many people, especially those in Belzoni that day, farm-raised catfish represent the food of the future: tasty, versatile, and inexpensive. It is a food worthy of celebration, and Belzoni comes through with a first-rate toast to the county's newest and most profitable industry. Preparing catfish the way it is served at the festival is simple, but to be authentically Southern, use only white cornmeal.

The World Catfish Festival is held in Belzoni every April. All events take place on a Saturday, on or near the courthouse lawn, except for the tours to the catfish farms. If you want to take a free tour (and we recommend it), sign up early in the morning — the first bus leaves at 10 a.m. The catfish-and-hush-puppy lunch is served from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m.; tickets ($4.50) are available at the festival. Otherwise there are no admission charges. Parking is on side streets or in local lots.

Belzoni is about 80 miles north of Jackson, on U. S. 49W. For more information write to the Belzoni Chamber of Commerce, P. O. Box 268, Belzoni, Mississippi 39038; or phone (601) 247-2616.

Fried Catfish Fillets

3 pounds catfish fillets

1½ cups white cornmeal

Vegetable shortening or oil for deep-frying

Wash and dry the fillets. Place the cornmeal on a sheet of waxed paper and coat each fillet with the meal; add shortening or oil to a deep-fryer or deep pot until the temperature reaches 375 degrees; add 2 or 3 fillets at a time and deep-fry until golden on both sides, about 3 to 5 minutes. Remove and drain the fish on paper towels while you continue to fry the remaining fillets. If the oil temperature drops below 375 degrees F, allow it to reheat before adding the next batch of fish, and don't add more than a few fillets at a time or the temperature will drop too much and the fish will be greasy. Serve hot, with freshly made hush puppies.

Pink Tomato Festival

Warren, Arkansas

Bradley County, Arkansas is the "Land of Tall Pines and Pink Tomatoes." It is also a land of hot sun, rich soil, and abundant moisture — all favorable conditions for growing large juicy tomatoes. The tomatoes from Bradley County are pink; that is, they are picked when the blush of ripeness begins on them, spreading in a faint star from the blossom end of the fruit. The tomatoes are weighed, graded by hand, and shipped to the Midwest. By the time the refrigerated trucks reach Ohio, Illinois, and other points north, the tomatoes are fully ripe and ready to be eaten.

The people in Warren — the Bradley County seat — are proud enough of their tomatoes to celebrate them every year at harvest time. Upwards of 70,000 people have come annually since 1956 to buy large quantities of tomatoes—bushels of them, in fact — so they will have enough to can for the coming year. They also come to Warren to eat fresh, vine-ripened tomatoes, to tour the tomato fields, to watch the tomato-eating contest, perhaps even to enter the tomato toss, and certainly to enjoy the All-Tomato Luncheon. This is the time each June when Warren paints the town "pink."

Tomatoes have been grown commercially in Arkansas since the 1920s, and today they represent a $7.5 million crop, half of which is totalled up annually in Bradley County. There are about 400 tomato farms in the county, utilizing about 48,000 acres. Visitors to the festival can take a free tour of some typical tomato fields to see how these fleshy vines are coaxed to grow between networks of cord in rows spaced about six feet apart. Their roots are heavily mulched with soil and the mulch covered with black plastic, so that the vines appear to be sprouting from long dark pillows. The irrigation lines run below the plastic mulch, so these pampered plants receive a steady trickle of moisture, allowing them to form plump juicy tomatoes while their roots stay warm under a soil blanket. The harvesting is done by hand each year and usually takes from five to six weeks.

The year we attended the festival, the organizers of the event were in a bind. The harvest was late because of a cool spring, so there would not be enough tomatoes to sell at the festival. To make matters worse, they had to use tomatoes from Florida for the tomato-eating contest and also for the tomato toss and the tomato bobbing. During the eating contest, the participants — especially the perky Miss Arkansas, Mary Stewart — grimaced at the thought of eating non-Arkansas tomatoes, and perhaps that is why even the winner only managed to eat two of the required four pounds in the given four minutes.

At the All-Tomato Luncheon, there were reports of people having been sent out to the fields in search of ripe tomatoes, in the hope of preparing some of the dishes with those Arkansas beauties. Well, they did manage to find some cherry tomatoes for the salad, and although they were a little more green than pink, they had that distinctive Arkansas flavor. The rest of the luncheon consisted of their pink-gold juice, a fresh tomato juice (in welcome contrast to the canned variety); ham with Bradley County sauce — a thick sweet-and-sour tomato-based sauce; green tomato beans with toasted almonds, which consisted of chopped green tomatoes cooked up with tender green beans (unfortunately from a can); "tomarinated" carrots — cooked carrots in a zesty tomato vinaigrette; and tomato finger rolls — light dinner rolls with a hint of pink. For dessert, there was the "heavenly tomato cake," a brownie-like chocolate sheet cake with a tomato-based chocolate icing. The cake was very good, even though an outsider would be hard-pressed to guess there were tomatoes in it.

During the luncheon there is a lot of talk about how wonderful Bradley County tomatoes are and how good tomatoes are for the county's economy. There are even some small jabs at inferior Florida or California tomatoes, which are picked green and gassed until they turn red (but remain unripe, as any supermarket shopper knows). The speeches — all by local officials and county agents — are brief and entertaining. Then the luncheon comes to a close with the auction of the boxes of tomatoes. Since this is a fundraising event the bids are usually high, and if the buyer is a man he often gets a bonus kiss from Miss Arkansas.

The Pink Tomato Festival in Warren is held to coincide with the pink tomato crop in early June. Festivities take place from Thursday to Saturday, with most events on Friday afternoon and all day Saturday. There are no admission charges; parking is on a side street, wherever you can find a spot. The All-Tomato Luncheon is held at noon on Saturday; tickets are $5.50, and may be purchased in the morning at the municipal building, across the street from the courthouse. The County Extension Service runs free tours of the tomato fields. Buses pick riders up right after the luncheon; otherwise, all events are held in the middle of town, mostly at the Courtsquare (in front of the courthouse). Local farmers sell tomatoes there too.

Warren is in south-central Arkansas, about 90 miles south of Little Rock, at the intersection of Routes 4, 15, 8, and 189. For a schedule of events write the Bradley County Chamber of Commerce, Municipal Building, Warren, Arkansas 71671; or phone (501) 226-5225.

Green Tomato Beans with Toasted Almonds

1/4 cup slivered raw almonds

1/4 cup butter or margarine

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/4 cup chopped green tomatoes

4 cups hot cooked green beans

In a saucepan, sauté the almonds in the butter over low heat until golden brown, stirring occasionally; remove from the heat and add the salt and tomatoes. Pour the tomato mixture over the beans in a saucepan and mix well. Serve at once. Serves 6.

Boggy Bayou Mullet Festival

Niceville, Florida

"Mullet? Where I come from even the cats won't eat it." This is what one man from Florida told us. Of course, in some parts of the state the shoreline is muddy and so the mullet, which are bottom feeders, taste a lot like what they eat. Elsewhere mullet are often considered trash fish, but along the Boggy Bayou on the Florida panhandle mullet are a staple food — eaten for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

During the second weekend in October the friendly people of Niceville hold a festival to show the rest of the world just how tasty mullet can be. A mixture of crafts booths and food stalls fill the fairgrounds, so you can wander down the aisles and sample the fried mullet from one booth, move along to buy a tee-shirt or handcrafted leather belt from a traveling crafts person, then step up to another booth where they might be serving smoked mullet. You can, of course, eat hamburgers and Polish sausages at the festival, but most people seem to crowd the mullet booths.

The Florida mullet is the migratory Mugil cephalus, commonly called the black, silver, or striped mullet because of the long black lines that run the length of its body. It has a tapered nose that broadens out to a flat, wide head. When it feeds along a shallow bottom its tail points skyward. The mullet can make a rapid switch from salt to fresh water by making a chemical change in its body that science has yet to understand. It leaves the Gulf of Mexico and swims up the shallow bayous each year to spawn. If caught with its delicate roe, the mullet commands a very high price. Unfortunately there is no roe at the festival, and few people eat it down here, perhaps because it has been part of the northern trade for so many years. When Floridians here do eat the roe, they usually deep-fry it.

Sport fishers catch their mullet with cast nets. They stand in waist-high water or lean from a pier and wait for a school to swim by. Then they fling their nets out in a graceful sweep. There is commercial fishing as well, mostly seine boats that go out into Choctawhatchee Bay for their catch. The Boggy Bayou has been an important center for mullet production for over a century, although the harvest has declined since its peak during the Depression, when large quantities of mullet were sold fresh, packed for shipment, or salted down for later use. People down here are trying to revive the industry, and hope they can again interest consumers in their versatile fish. The festival is part of this effort.

The Boggy Bayou Boys — a local sportsmen's club — fix the mullet in two very appealing ways. They've been doing it since the festival began in 1977, and they assured us that they will be there in years to come. The fried is the most popular, and it's easy to see why. They head the fish, split it open, and remove the bones. Then they butterfly the fish, dust it faintly with a mixture of flour and cornmeal, and fry it in vegetable oil. The fish emerges virtually greaseless and very crisp, especially around the edges. It's served with just hush puppies, or on a platter with cheese grits, beans, and hush puppies.

The smoked mullet has also been headed, cleaned, and boned. It's then sprinkled with lemon juice, Worcestershire sauce, and melted butter. The fish is given a "heat smoke" — a combination of smoking and cooking — for an hour to an hour and a half. When the fish starts to change color, the cooks baste it with more of the lemon juice mixture. The mullet ends up as a very moist, lightly smoked fish — not at all salty because it hasn't been cured first. We found that the white meat on the fish picks up the smoky flavor divinely, while the dark meat seems to retain more of its fresh fish taste.

Most of the mullet at the festival is fried, but one enterprising stand, with a wonderfully aromatic barbecue pit, prepared barbecued mullet sandwiches: Pieces of smoked mullet were placed briefly on the pit, then served up on a bun with a spicy tomato-based barbecue sauce.

The grounds of the festival are shaded by giant live oaks, and large round tables are placed conveniently near the food booths so that you can rest your plate and drink while you are eating. One part of the lawn is a center for recycling the beer and soda cans that usually litter most festivals. Although thousands of people attend this festival each year, a comfortable, small-town feeling pervades. On stage there is a bang-up performance by the Golden Eagles, the high school band — so large it must include the entire school population. There's other entertainment too, including country music, clogging, jazz, and rock. This festival has no rides but does feature the expected beauty pageant, foot race, and evening dance. The festival organizers tend to refer to this as a party, and explain that they try to follow the example of the mullet: "the plentiful fish of the area which has, over the years, given so much for so little."

The Boggy Bayou Mullet Festival is held the third weekend in October in Niceville, at the old Saw-Mill site — a large city park just to the north of town. There is some entertainment on Friday night, with dignitaries and opening ceremonies. Most activities are on Saturday starting at 8 a.m. (though when we got there at 9, not a whole lot was going on yet). The Golden Eagles kick things off on Saturday with an hour-long concert. After that most people seem ready to eat some mullet. A fried mullet plate runs about $3. Cokes, barbecues, hamburgers, and snow-cones are also for sale at various booths. The music goes on all day and into the night as well.

There is no admission charge; parking is well-organized in a large field adjacent to the festival site. Large shade trees have benches underneath for cooling one's heels after lunch. There are bleachers in front of the stage. Although the Mullet Festival draws upwards of 150,000 people (over the three days), we never felt crowded or jostled.

Niceville is on the Florida panhandle about 60 miles east of Pensacola; take Route 85 south off 1-10. For further information write or call Boggy Bayou Mullet Festival, Inc., P. O. Box 231, Niceville, Florida 32578; (904) 678-3099.

Deep Fried Mullet

From the Boggy Bayou Festival, here is T. H. Lovell's recipe for fried mullet.

2 pounds mullet fillets

Salt and pepper to taste

Cornmeal for dusting

Oil for deep-frying

Rinse fillets, then dry thoroughly. Season with salt and pepper, then dust generously with cornmeal; heat oil in large pot or deep-fryer to 350 degrees F; place half the fillets in the pot, being sure not to crowd them. Fry with skin side up first, for about five minutes, until nicely browned; then turn and fry skin side down for five minutes until brown. Drain on paper towels while you fry the remaining fillets. Serve with cheese grits.

Yambilee

Opelousas, Louisiana

The Yambilee is one of the oldest harvest festivals in Louisiana, first celebrated in 1946; and it's held in Opelousas, the third oldest town in the United States. Although called yams, these delicious copper-skinned tubers are really sweet potatoes, and they've been something to celebrate since 1690, when European settlers found Native Americans eating them. Already "tested" by the Attakapas, Alabama, Choctaw, and Opelousas tribes, the tasty, nourishing sweet potato became a favorite food of the French and Spanish colonists.

Yambilee has become a permanent part of the lives of the people in this Acadian city. "I grew up with Yambilee," said Bill Bourdier, president of the thirty-eighth annual festival. "My first year I was in the children's parade, and, with eight other kids, we pulled a float. Then there was a torchlight parade and a Yamba parade (all black people). The Yamba parade was always the best one."

Things are different now. There is only one parade, the Grand Louisyam Parade. But a wide variety of events are now included that probably weren't a part of Yambilee's past: a talent show, arts and crafts, a diaper derby, a children's costume contest, and a senior-citizen dance. Most important are the exhibits, the yam auction, and the coronation of the yam queen and king. Neighboring "royalty" — queens from other Louisiana festivals (International Rice, Shrimp, Rayne Frog, Swine, and Orange) — are invited to the festivities. The yam auction is a big fundraiser. The Queen of Yambilee auctions off a box of the best (Centennial variety) yams. Bidding is competitive, and the winner usually gets a kiss in addition to a box of potatoes. The exhibits include agricultural displays, homemade foods, and the fanciful "yam-i-mal." The farmers bring in boxes of beautiful sweet potatoes: Gold Rush, Golden Age, Heart of Gold, Jewel, Centennial, and Travis are the big varieties. Centennial is the most popular and to our palates the best. It is the favorite variety to grow because it has a high sugar content, is disease-resistant, and offers a high yield. It's a mighty good-looking tuber, with a smooth skin and firm orange flesh that bakes to a sweet intensity that never becomes cloying. The Centennials that we saw on display at the fair (and that we took home with us from the festival) were truly beautiful specimens, making the sweet potatoes that we can get from supermarkets seem crude and course.

As with most harvest festivals, there are competitions. Cooked yam dishes are a popular entry in the home economics department. Although they sounded good and looked appetizing, they were unavailable for sampling. The most popular competition to enter is the Yam-i-mal, which has five classes — four-year-olds through senior citizens. Yam-i-mals must be made from one odd-shaped sweet potato that resembles an animal, left in its original shape and color. "Add feathers, construction paper, pipe cleaners, playdough, or such to complete the animal appearance; but remember that the least amount of decoration added, the better," say the contest instructions. Some of the more entertaining creations were an armadillo, a turkey, a dinosaur, an elephant, and a mouse. The prize winners are then used as centerpieces for the Royal Luncheon, at which baked Louisiana yams are served.

Unfortunately, we didn't find many sweet potato dishes to eat at the Yambilee, other than yam cupcakes and fabulous sweet potato pies, which were available at several booths. We sampled them all and would be hard-pressed to have a favorite, though we did slightly lean toward the ones at the Ebenezer Baptist Church Matron's Society booth. Bill Bourdier told us about another Louisiana treat: a yam in a bowl with a rich gumbo poured over. We later tried that combination and recommend it highly.

On the midway were many rides, games of skill and chance, and other side-show attractions. With over 35 years behind it, the Yambilee is good entertainment. We would have preferred more yams, though; and we would like to have been able to come circa 1955 (before the Yamatorium was built), when the festival really took over the town.

The Yambilee is held in Opelousas near the end of October. Although the festival kicks off with a talent show on Wednesday, most events don't start till Saturday; the exhibits open that day as well. The yam auction and the Louisyam parade are on Sunday. All activities take place on the Yambilee grounds. Sweet potato pies and other foods are for sale on the grounds; a pie costs about $1. There is plenty of free parking. No admission is charged to the exhibits or grounds, but some events — such as the Royal Luncheon and the Grand Ball — have modest ticket prices. Tickets are sold on the grounds (at the Yambilee office) or by mail from the Yambilee (see below).

The Yambilee grounds are located just west of town. Opelousas is on U.S. 190 about 60 miles west of Baton Rouge. For more information contact the Louisiana Yambilee, Inc., R O. Box444, Opelousas, Louisiana 70570; (318) 948-8848.

Old-Fashioned Candied Yams

This is a recipe adapted from one given out at the festival.

10 medium sweet potatoes, peeled

1 cup sugar

1/2 cup brown sugar

1/2 cup butter or margarine, melted

1/2 cup dark com syrup

1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

1 teaspoon ground nutmeg

1/4 cup water

1 cup shelled pecans

Preheat the oven to 450 degrees F; slice the yams like thick french fries, then place in a large casserole. Add the sugar, brown sugar, com syrup, butter (or margarine), spices, and water. Cover and bakefor45 minutes. Just before serving, remove the cover and sprinkle the pecans on top. Bake for an additional 10 minutes, then serve. Serves 6 to 8.

Tags

Carmen Taffolla

Carmen Tafolla is the author of To Split a Human: Mitos, Machos, y la Mujer Chicana on Chicanas, racism, and sexism, published by the Mexican American Cultural Heritage Center of the Dallas Independent School District. (1986)

Carole Berglie

Alice Geffen edited and wrote the introduction to the classic The American Frugal Housewife, by Lydia Child (Harper & Row, 1972). She is the author of A Bird Watcher's Guide to the Eastern United States and has written and edited a series of nine major books, The Spotter's Guide. Carol Berglie is cookbook editor of Barrons Publishing Company.