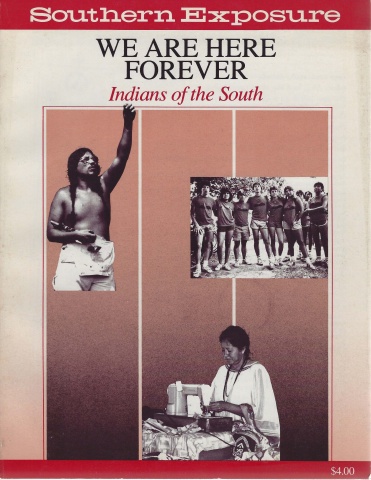

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 13 No. 6, "We Are Here Forever: Indians of the South." Find more from that issue here.

The voices of Native Americans of the South are not pleading; they are demanding. A small but potentially powerful force in the American Indian struggle for self-governance and self-determination, the indigenous people of the South continue to wage their 400-year struggle against the ceaseless efforts of Europeans to remove them from their lands - and from the collective national memory. Many of the current struggles are being waged in the courtroom - and the Indian people are winning. Southern Exposure has long been dedicated to reporting critical issues in our region and chronicling efforts by individuals and organizations to achieve social and economic justice. This survey of happenings in Indian country follows that tradition. We intend "We Are Here Forever" to serve as an educational resource, to be used by high school students, community activists, public officials, and educators.

Each of the contributors to this volume uncovers a piece of a complex history, a unique heritage, and the set of contemporary challenges confronting native peoples of the South. Besides just telling the story, we hope to challenge progressive thinkers and social change activists, both black and white, to deal honestly with issues of the rights of indigenous people, and to do so from an informed position.

When Southern Exposure began to lay the foundation for this special issue several years ago, we often heard the skeptical statement, "I didn't think there were any real Indians left in the South." The stereotypes about indigenous people embodied in that statement reflect the successful efforts of white America to obscure the reality of native peoples' existence and replace that reality with a series of myths that condone past genocidal practices and mask the current conditions which are the legacy of that past. But Indian people directed us to say, "We are here forever."

Early stereotypes, remarkable for both their ambivalence and their tenacity, have variously depicted native peoples as noble savages, bloodthirsty savages, drudging squaws, Indian princesses; Indians have been branded as sexually promiscuous, intemperant, imprudent, childlike, and in need of guidance or governance. But perhaps the most harmful myth of all is the one that denies the existence of lndian people as living, contemporary beings. The commercial media, our window to most of the world, reinforces these myths and images. Our educational institutions provide little more in the way of substantive information. Outside of university walls, information about Southern Indians is decidedly lacking.

The Indian people have had to contend with more than the psychological disadvantage imposed by myths that deny their existence. They have also had to ustain themselves through continual shifts in national policy - based largely on the codification of these myths. These policies not only have abridged Indians' rights as individuals but have posed a continual threat to their collective status as sovereign nations. The Indian people occupy a unique position on the national political scene. They cannot be considered just another "minority" group: as John Folk-Williams points out in "Readers Corner," their status as treatymaking nations is too well established in both legislative and judicial history. Yet the capriciousness of national policy and continuing land greed means that some North American natives today must still battle with the government to survive.

In spite of concerted attempts to have Native Americans disappear through forced assimilation, relocation, removal, and murder, the native population is on the rise. Three legislative factors - the promulgation of regulations for official recognition of tribes, the Self-Determination and Education Act of 1975, and the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 - all significantly increased the opportunities for Indian people throughout the U.S. to halt, through legal advocacy, the trend towards cultural and political (if not actual) extinction.

Perhaps the single most significant factor in this reversal is not legislation, however, but the leadership and participation of lndian people themselves. Previous efforts at reform have generally been led by well-meaning whites. Now the Indian people have organizations such as the International Treaty Council formed in 1974 to represent the traditional tribal view that emphasizes nationhood; the Ohoyo Resource Center, founded by Owanah Anderson in Wichita Falls, Texas, which has developed a comprehensive training program designed by and for Indian women to increase education and employment opportunities, especially within federal Indian agencies; and the Native American Rights Fund which has directed the energies of talented legal staff towards achieving belated justice for a number oflndian tribes. The Native American Rights Fund's record in the South alone is impressive: through its efforts the Tunica-Biloxi received federal recognition, the Catawba are moving ahead with a 144,000-acre land claim, and the Alabama and Coushatta, one of the tribes "terminated" by the government in the 1950s is suing for damages. T

he Indians in the Southern states, while sharing common concerns with Indians throughout the continent, bring a heritage and history peculiar to the region. Bearing the brunt of the initial European efforts to control the continent, their numbers were decimated early by the wars between the French, Spanish, and British; their social systems were undermined by brutal proselytizing efforts; their economic system was replaced by one that encouraged the destruction of the ecology and exacerbated conflicts with neighbors; and fatal diseases were introduced to which they had no immunity. Dave Wilcox documents this process in a look at the beginnings of alcohol and deer as trade items.

Three hundred years before General Tecumseh Sherman led his war of extermination against the Plains Indians of the West, small remnants of once numerous tribes had been herded into villages that could more accurately be called work-camps, to serve the needs of the Spanish invaders of the Southeastern coast. Robert Lynch traces one of the least discussed aspects of cultural imperialism perpetrated by Europeans - the origins of homophobia in the Americas. In this early era, Indian secular and religious practices of all kinds were considered abominable by the Christians, justifying the destruction of the native culture.

The early colonials and later the United States government did not simply condone but demanded the destruction of the "real" Indians and of their religious, social, and economic systems in order to make way for those of the "superior" Europeans. Continual warfare plagued native people during the formative years of the American republic until the final solution was proposed in the Removal Acts of the 1830s, forcing the exile of the five so-called "civilized tribes" - the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Cherokee, Seminole, and Creek - to the Oklahoma territory.

These tribes, who held the most desirable land and resources, posed a threat to the plantation society of the South. They had adapted to the slave-holding, patriarchial economy of the region; a small number held slaves themselves. Consequently they had retained much influence and power in the new economic order. In spite of intermarriage with the white traders and settlers, the status of these tribes as sovereign nations threatened to halt the expansion of white control over the region. Through trickery, military force, and outright defiance of its own laws, the government succeeded in removing the majority of the Indians then living east of the Mississippi into Oklahoma where contemporary wisdom decreed that no whites would want to settle, the land being deemed worthless. Yet remnants of these tribes remained in the South, retreating into mountains, swamps, and other protected enclaves. The Cherokee, the Choctaw, the Chitimacha, the Seminole, and the Miccosukee who remained in the South eventually received some federally reserved land.

While the history of how those nations fared in their transplanted homes lies outside the scope of "We Are Here Forever," the historic reunion between the Eastern and Western Cherokee at the sacred ground of Red Clay, Tennessee in 1984 was an opportunity to witness the efforts to heal a 147-year-old wound as the tribal councils met again for the first time since Removal. Marilou Awiakta gives us a deep appreciation of the healing process taking place there. And the Remember the Removal project, organized by the Cherokee Board of Education of Oklahoma in cooperation with the Eastern Band of Cherokee, highlights the current efforts by this divided nation to begin a process of spiritual and familial unification and to provide mutual political support.

Two politically significant events followed this historic reunion. In October 1985 Ross Swimmer, former principal chief of the Oklahoma nation, was appointed head of the Bureau of lndian Affairs. At the same time Wilma Mankiller, former deputy chief of the Oklahoma nation, became principal chief, rebuilding a tradition of shared leadership between men and women that had previously been submerged by the impact of European-style patriarchal rule on the political life of the Cherokee.

In spite of the removal efforts, many small or weakened nations were allowed by state governments to remain in the South because they constituted little or no threat to their surrounding white neighbors. Among these were the Alabama and Coushatta of Texas, various state recognized tribes in Virginia such as the Pamunkey, and the Catawba of South Carolina. But those remaining were quickly subject to suppressive state laws abridging the rights of all "free people of color." Political expediency and the survival of white supremacy demanded that the remaining Indian people be included in that category. In many states, Southern Indians after 1835 were no longer even legally classified as Indians. Those who had state reservation lands, as a number of tribes in Virginia did, were objects of virtual crusades to disprove their heritage - by pointing out their lack of pure "Indian blood" and their tendency to associate with free people of color - in order to gain white access to remaining reservation lands. Census takers began to classify these Indians as mulattos, negroes, or colored, terms which eventually were collapsed into black - and indeed many families did become and remain part of the African American community. Many did not, and their descendants, sometimes numbering fewer than 100, still reside on the state reservations established in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Today, the popular imagination accepts the notion that real Indians wear feathers, ride horses for transportation, and are safely tucked away out of sight on reservations where we may go and see them practicing their quaint cultures and living picturesque lives. This attitude fails to take into account the resulting impoverishment of those nations that resulted from the failure of the government to live up to its agreed-upon obligations to provide certain services. While fewer than 14,000 of the 188,000 Indians residing in the Southern states live on federal reservations, those who do have been forced to live a marginal existence as tourist attractions while the construction of dams and the strip mining and timber industries have changed the face of the land, making survival by farming, hunting, and fishing a virtual impossibility. Leslie Marmon Silko, prior to the 1984 election, interviewed an Indian woman identified only as Auntie Kie. She records:

The federal money which used to come to the Indian communities may have been labeled "assistance." But for the Native American people, that federal money wasn't "welfare" or "aid." It was money that has been owed to the Indian people for over 200 years. Another four years of Reagan will only get the United States farther behind in its payments on the Big Debt owed for all the land wrongfully taken and the damages resulting to Native Americans.

In a moving speech before the Florida state legislature, James Billie speaks of the Seminole nation's twentieth-century efforts to retrieve its people from from the hun tashuk teek, the "apathy," the "dependence on the unnatural" which has invaded their lives. "I was a product of another third world," he tells us. The Seminole are boldly using their sovereign status to circumvent state laws which would deny them the only opportunity they have had in four centuries to compete in a foreign economy. The history of defiance which gave them their name continues in Seminole country and once again the whites are up in arms. It is a continuing history.

Part of the requirement for Indians to receive their just due from the government is that they be recognized by the U.S. as “real.” Bruce Duthu and Hilde Ojibway examine the efforts to gain federal recognition and what recognition means to several Indian tribes in Louisiana. In a related story, Forest Hazel describes the particular status of the Indian people of North Carolina, where various state bureaucracies insist on classifying them as “other”— after first attempting to designate them as black or white. One of the few states which grant state recognition to Indians who are not federally recognized, North Carolina is home to the Lumbee, whom Bruce Barton, editor of the Carolina Indian Voice, calls “anthropological delights” because of their unique history. Their struggle for survival in hostile white territory embodied in historic Reconstruction-era guerilla warfare waged against the unreconstructed Home Guard; their establishment of an Indian Normal School in 1887, now Pembroke State University; and their sheer numbers make them a force to be reckoned with in Indian affairs.

In spite of the diversity of issues and histories presented here, there was among all the Native Americans we contacted no sense of themselves as a people whose culture had been "lost." None thought of themselves as relics of the past. Struggling with efforts to maintain and renew the best of their heritage, while accepting the challenges of the present complex era of threatened nuclear destruction that we all face, has forged dynamic communities. "We are here," they asked us to say. "We are just who we are. We have always been here and we are here forever."