Two Generations: A Horse

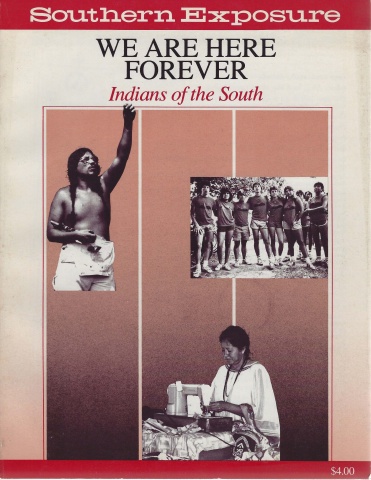

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 13 No. 6, "We Are Here Forever: Indians of the South." Find more from that issue here.

My father's stories sometimes crop up in my work. They become pieces of the written story, like a finger that points the way, or a leg that helps the story to walk. Sometimes they are the heart, giving the writing its oxygen and blood.

He wrote down the story of the black horse and turned it over to me. I suspect it was to make sure that I got it right at least once, because I not only fictionalize, but I have my own memory of the stories and how I heard them, and my own version of the truth.

I no longer think of my writing as "telling the truth." Adhering only to facts limits the work, and I wonder if truth-telling is possible, given how human perception works. Writing is a way to uncover and discover a new truth. It comes from, and speaks to, the deepest wellspring of the human being, the place that is the source of our inner knowledge, intuition, and instinct. Fiction clarifies the world without muddling life with the bias of fact.

"The Black Horse," in my father's style, is wonderful and rich in texture. He thought I would "fix" it for him. I felt it was whole in itself, but I had been wanting to write about Shorty for years. I wrote several drafts of a poem about that horse; not one version worked. For months I looked at my father's story. When my father wrote of Grandfather falling, drunk, off the horse and how the horse stayed with him, I remembered my grandfather riding in one night during an Oklahoma lightning storm. I watched, afraid, from the window. Years later, the incident became a poem in my first book:

Silver light down the dark sky

stops the man we love

and fear between heartbeats.

It's dark.

The place where he stood

is empty with night.

Behind the fences,

nitrogen and oxygen

are splitting apart.

—from "Remembering the Lightning"

I remembered, also, reading my father's story, how my father broke and trained horses later at a ranch south of Colorado Springs, and how he put me on their backs as extra weight. When he wrote of bronc riding, I pictured all the rodeos we attended, Casey Tibbs the star, girls in gold lame Western pants, my uncle Jake who is a farrier and specializes in rodeo horses.

My dad mentioned Nathan Woodward, the man who married my aunt Louise, who grew cotton and winter wheat, who told me once about the death of my grandfather’s red mules and his land loss during the Depression. Last summer my daughter Tanya and I walked through a long and dark corridor of cedars to the cemetery in Martha, Oklahoma, to visit his grave.

In my memory, also, I could see my father studying math and English. I pictured Will, who sin my story as that student. He is at least half my father. And hearing the men speak Chickasaw has turned through my bones all my life. I knew there was something here that I wanted to write. I laid aside my father's story in order to get close to what I wanted to say. What I noticed about "The Black Horse," his story, was that at the end there was a difference between what my father said and what I had heard in the past. For instance, I know that things were not too good for Indians in the territory. The time was right after the oil boom which resulted in loss of Indian lives and land. It was right after statehood,in 1907, which my Chickasaw grandparents never acknowledged. It was just prior to the Depression. And the majority of lndian Territory stories were violent and fearful ones; it was my father who told me about the night riders coming by and his father concealing a gun as he walked out of the house to meet the men on horses.

The allotment where my father lived as a boy is now the Ardmore airport. I have heard how it once looked, where the black pasture was, the water. But I created the story around the land I remembered from childhood and family visits. I added the history I remembered from some reading, and an incident related to me by Carol Hunter, an Osage scholar of that time period. I added the illegal timber industry that partially created the dustbowl. I added my cousin Coy Colbert and his maps of our lands that are currently leased out by the BIA with no payment to the tribe. The story grows to become a story of Indian life and land.

"That Horse," in my version, is mostly fiction based on history, on my father's stories, on my own experience. I had to let my father's story go in order to write it. His story is his. My story is mine. My grandfather would have another way of telling it. Together we created an illustration of how the oral becomes the written, how life becomes a story, how new angles and layers of information create a form of energy that lets the story enter.

It was through my father's imagination that the writer in me was nourished.

The Black Horse: Shorty

By Charles Colbert Henderson

The horse traders used to come by in a wagon leading the horses behind the wagon. Some of them would be riding horses or driving them. They would go around the country and trade horses or anything else they might have.

If they had a horse you thought might be better than yours, then you and the horse trader would start to talking trade. Sometimes it would take a day or two to make the trade, and this was because he would always want something else. That was called "boot." It would usually be money. He might say that he would trade his horse for yours if you gave him $25 to boot, maybe less or maybe more. It always turned out that he would want something, for that was the way he made his living.

One day a horse trader came by our house and had several horses he wanted to trade. We always had several horses in the horse lot. This time my dad didn't want to trade, so they just talked and the horse trader had dinner with us. My dad had known him for a long time. He was leading a little colt behind the wagon, and after a while of talking and visiting they went out to the wagon. This man did not want to lead this young horse around the country, because he was about a year old and it wasn't good for him to be exerted that much.

He wanted money for the colt, and they bartered for quite some time. Then Dad went to the horse lot and caught a horse and led him out. He was tied to the wagon and the little black horse was untied and led to the barn. He was not put with the other horses. Instead he was put in a stall and fed oats and hay. He was given special treatment from that day on. When he put on some weight he was the blackest horse I ever saw and was slick and shiny like silver. He flashed in the sun when he ran around the lot. He was not ever let out with the other horses in the pasture. He stayed in the barn except when dad took him out for water and walked him around the place. He got gentle and was brushed often to keep his coat shiny.

He was something special to my dad, and he wouldn't let us kids have anything to do with him like we did with the other horses. He was my dad's horse and we all knew it. We rode all the other horses and fed and watered them and used them like all animals were used on the farm. If we wanted to go to the other end of the farm, or take water to the working hands, we would just jump on a horse and carry the water to them. I was small but we had a stump that we would get on and from there we could get on the horse with ease.

Shorty grew into a very good animal; however, he was not as large as most of the horses on the ranch. He was stocky and strong. He was quite fast for a short distance. He stood out in the presence of other horses. When he was about three years old, my dad began his training. With a rope and a halter he was being taught to lead and to react to the halter (called "halter broke") and he got to the point where he would just follow my dad all around the horse lot and all over the place. He was very gentle and never kicked or objected to any of the kids petting him. They could walk under him and he would stand perfectly still, as if he were afraid of hurting one of them. That was quite different from the way the other horses acted. They did not want anyone bothering them. So all the kids liked Shorty very well.

When it came time to break Shorty to ride, we all thought that would be a good show. Dad had put the saddle on him several times before then and let him walk around for some time with it on and he didn't object, like most young horses do. They usually buck and pitch a lot when first ridden. In fact, it took a bronc rider to ride some of them. My oldest brother Rip was a good rider and could ride bronc hors very well. But he was no match form) dad, who was as good a bronc rider as there was in that country at that time. He was also the best horse trainer in the country.

The time came to ride Shorty. My dad saddled him and led him out to a lot that was vacant of any animals. We all gathered on the fence to watch. I mean all: my mother, my sisters, and us boys. Well, we were somewhat disappointed, I guess, for we were expecting to see a good bronc-riding show. My dad put on his spurs, pulled down his hat so it wouldn't blow off, pulled Shorty's head around to the mounting side and held it while he put his boot in the stirrup and gracefully swung on top of the horse, and settled in the saddle ready for the worst.

He was surprised, for when he turned Shorty's head loose, Shorty just looked around and started walking around the lot. Dad would rein him in all directions around the lot and started him to trotting and then into a gallop and the horse obeyed as if he had done this all of his life. He never did buck and was very smart and learned all there was to learn in record time. It wasn't long until he was a good roping horse and from that day on he was my dad's working and riding horse.

I know of the time my dad drank too much when he was out checking the cattle west of the town of Berwyn. He got drunk and fell off Shorty. Well, he went to sleep and Shorty stayed with him all night, just waited until Dad woke up and rode him home.

If my mother didn't like the things we did she never said anything before us kids. That way we never knew if it made her mad or not. I never saw her angry in my life. Even so she would tell us, if we did something we were not supposed to do. She would tell Dad and usually that was enough for us. He did all the correction and punishing of us children.

Dad was training the horse all of the time. On the weekends there was always a group of ranchers getting together and having calf- and goat-roping for money. They would all put in so much money for entrance fee. The one with the fastest time roping and tying an animal was the winner. It was a lot of fun and it was seldom that one cowboy would win more than once. They were all about even in this event. It would last all afternoon and everyone would have fun. There was always someone selling pop and lemonade, cookies, and hot dogs.

Dad rode Shorty and he grew better all the time. Some of the ranchers would let other cowboys ride their horses to rope on, but Dad would never let anyone ride Shorty except him. He would not let Rip ride him to rope off of. He was a one-man horse.

Once Dad rode Shorty up to the house and dropped the reins as he always did, for he knew the horse would be there when he got back. Well, I was a cowboy too; I had ridden all the gentle horses and I was at the age I thought I was pretty good and in control of everything. I went out and got on Shorty and was going to ride him. He was all right as long as we were around !he house and barn. I took him out in the pasture for a gallop. That was my mistake, for instead of just a gallop he started to run and I could not stop him. He clamped down on the bridle and bit and it did no good for me to pull on the reins. I could ride him without any trouble. I just could not stop him. I thought about jumping off, but that was dangerous so I stayed on him, all the while trying to stop him. By the time I came by the house the first time everyone was watching. Well, my dad hollered at me to bring him by the barn and I knew he would grab the reins and stop him. I did that and when we came by, my dad could not catch the reins and we were out to another pasture. There was a pecan grove in this pasture, and I decided that I would run Shorty into a tree and stop him. Well, he was smarter than that. He would just go around the trees and keep on going. By this time I was beginning to panic and all I wanted to do was get off that crazy horse.

In the meantime, my dad had gone to the barn and caught the old blue horse and here he came, and I guided Shorty close to him. Shorty was getting pretty tired and so was I. And Dad just rode up beside us, caught the reins, and stopped him. He started to lead him back to the barn, and he asked if I was all right and I said I was. Well, I knew by the way Dad looked at me that I wasn't going to be so good in a little while. I said I wanted off and would walk to the barn. He told me to stay on the horse. When we got to the barn he unsaddled Shorty and took the reins to the seat of my pants. I knew I deserved the thrashing and took it like a man should.

Later on we were moving a herd of cattle from the river bottom during a flood. We had been gathering them since four in the morning. We had them all and were moving them to higher ground and Dad rode up beside me and smiled at me and said, "Would you like to ride Shorty?" I knew it was supposed to be funny, but somehow it was not. I told him that I would never ride Shorty again. He laughed and rode on up the side of the cattle.

Nathan Woodward was helping us with the cattle. He smiled and said to me, "Everything is all right, Pete."

Everything was all right for we got about 400 head of cattle out of the bottom and if we had not there would have been a lot of them that drowned. It flooded for a week or so. From then on my work got harder and the hours got longer. But that is how it goes on farms and ranches. The work was hard but I never minded it.

As I look back, I think I really liked the work. There was always something that needed to be done and there was always time to play. If we wanted to go fishing, I can't remember any time that my dad would say no. When we asked him if we could go fishing, he would say it was all right and give us a time to be back. We never failed to be back when he said, or close, for we didn't have watches and neither did he. We knew that there was work to be done and that if we did all of it we would be able to do the things we wanted to do, like fishing, hunting, swimming in the river. We had a lot of kids in the country and we were always getting together and playing games and such things that kids did.

Shorty lived a long time and died of old age.

That Horse: 1921

By Linda Henderson Hogan

The dream men wore black and they were invisible except for the outlines of their bodies in the moonlight and the guns at their sides. Will walked slowly behind them until their horses turned and began to pursue him. He could not run and they had no faces in the dark.

It was early morning and his heart was pounding like the horses' hooves. The crickets were singing but there were no birds. Will pulled on his jeans and boots. Outside, mist was snaking over the land between trees and around the barn. It absorbed the sounds of morning. The rooster crowed as if from the distance.

The horse trader stood beside his wagon talking to old man Johns. He had arrived in Will's dreamtime with his horses of flesh tied behind the wagon; an older paint, a white stocky work horse, two worn-out mules, a drowsing bay, and the black colt. Will eyed them while he walked to the barn.

Will's father stood leaning against the rake as if he'd been caught hard at work. It was clear by the way he stood that he didn't want to trade.

"I been to Texas and all over." The trader removed his hat and wiped his forehead with a rag, though there was a chill in the early morning air and ghosts were flying from the breathing mouths of horses.

"Picked up that bay over there in Tishomingo."

Will stood just inside the barn, watching the men and listening.

"How's the Missus?" the trader asked as he pulled back the lips of the bay to show Mr. Johns that her teeth were not worn down.

"Just fine."

"The boys?"

Mr. Johns was not interested in the bay, but he put aside the rake and helped the trader through the steps of his work, lifting her leg to examine the hoof. The horse pulled away and twitched the men's touch off her back. She already knew what Will had begun to suspect, that a danger lies in men's hands, that whatever they touch is destroyed. She shook their bitter taste from her lips.

After the men went indoors, Will looked over the horses. He was curious about the contents of the wagon, the leather pouch alongside ropes and horse blankets, the extra saddle and burlap bag bulging with trade goods.

In the kitchen, Josie served the men thick slabs of bacon and cornbread with eggs. Will sat quietly. His brothers had gone to put up a fence at Uncle Roy's so it was a silent morning without their loud boots hitting the floor, without the young men's disordered conversation.

"I got this black colt too young to travel. Comes from real good stock."

"I got no need for a colt. It don't look too young to travel."

"You can give me that work horse out there - it's nearly broke down anyway, see the sway of its back? And give me five dollars to boot, I'll give you that colt. An Indian around here has need of a black horse."

Steam boiled up from the kettle. Josie held her hands in the heat of it.

The trader continued, "Picked up that colt from that new white sheriff over in Nebo County."

"That so? Haines?"

"That's the fellow. The colt's too young to travel."

"Haven't got five dollars anyway." Will's father rubbed his chin. ''All I have is dried meat."

"That'll do."

Will didn't know where the riders came from or where they were going. All that year, his father rose from his bed at night and went outdoors, his pistol concealed at his side. He ex- changed words with the men who rode out of the darkness, or he fed them or gave them money, or offered them fresh horses for their journey.

Sometimes they sat around the table like bandits, all of them dressed in black, their dark horses hidden in the trees. Or they sat on the front porch where they would not disturb Josie and the boys, or Will, who was supposed to be studying arithmetic. The men sat with their boots up on the rail, their chairs tilted back on two legs. Will heard the words again about the sheriff, oil accidents, manhunts. Heard the whiskey bottle hit against a glass and return to the table.

About this time, a Choctaw family named Hastings who lived nearby had all disappeared except for the grandmother who was declared mentally defective. She was taken away, protesting in Indian that the sheriff and deputy had murdered her sons and daughters, and that the government officials wanted her land and the mineral rights. The sheriff who hauled her off did not understand the language she spoke. He said she was crazy as an old bear because her family had gone off to Missouri after work and jobs and left the old woman behind. The grief of it was about to kill her, he said, and she'd be better off in the hospital up in the city. But James Johns and old man Cade, a fullblood, heard the old woman’s words and understood. They knew she never lied and she was sane as a tree that had watched everything pass by it.

“She’s crazy, all right,” lied Cade to the sheriff. “Says there’s ghosts on the place.”

Afterwards, when they went to the hospital to talk to her, she agreed to stay there until it was safe to return to her allotment land. They didn’t tell her that the land was already torn up and that it spit blue flames into the night from the oil works and that the small pond she had loved was filled in with earth.

In the hills there were the bodies of Indians, most of them wrapped in blankets, the smell of whiskey on clothes of even those who were known teetotalers and Baptists.

Mr. Johns's face hardened, but he set to work. His routine included brushing the horse, Shorty, until the black fur was like water reflecting the sun. He kept him separate from the other horses as if they would give the men's secrets away to that one who had been owned by Sheriff Haines. The horse heard only the voice of James Johns. As it grew, it was enchanted by the man's voice and tales. Mr. Johns allowed no one else near the black horse.

He grew muscular, that horse, and his stamping hooves shook the ground.

One day the Indian agent arrived at the door. Mr. Johns said to Will, "Don't you ever forget that the only goal of the white men is to make money." And he went out like he had nothing but time and stood on the front porch and looked squarely into the agent's face.

The young man was fair-haired, like corn silk, and had flushed cheekbones. He gave a paper to Mr. Johns. "You are good honest people and you have been wronged. If you sign this you will be repaid for your damages over there by the Washita."

Will thought the young man looked sincere enough.

"I don't sign government papers," said Mr. Johns.

"Uncle Sam's been real good to you, hasn't he? Just your 'John Henry' is all you need."

"No, I don't sign them."

A week later, Mr. Johns returned a check the agent mailed to him, knowing that to cash it would legally turn his land over to the oil men.

The riders on their shadowy horses arrived like the wind. Will heard the horses out in the trees and wondered if the agents were stalking the house around the boundaries.

There were more men than usual. There were even a few older gray-haired men, those who wanted to go back to the old ways. They were talking about dangers and people missing from their lands and homes. They sat at the table with an open map of Indian lands, and when the door crashed open one of them hurriedly tried to fold it away.

Will went pale with that crashing and there were demons of terror in him when Betty Colbert rushed in. She was in a terrible state. Josie, about to offer her some coffee, backed off when she saw how Betty's face had darkened, how her hair was wild and her eyes furious.

Betty was breathing like a runner. "You men tell us we're in danger and don't tell us anything else that's going on and then you go off at night leaving us alone with just a gun. To shoot who, I want to know?"

Will was already in the room. He was drawn in by the angry power of this woman whose voice came from the house of wind up in the hills.

Mr. Johns said, "Your house is protected, Miss Colbert. My older boys probably followed you here to make certain you are safe."

And though he was carried into it, Will had a feeling beneath his heart that he wanted to cry. His brothers were not helping uncles after all but were out there at the edge of the clearing, watchers in the dark, hidden from the thin lights of houses.

"This didn't used to be such a hard country," Betty Colbert said. She sat down, almost in tears. "Then they go and cut down all the timber and the young people disappear when they get old enough to sign over their land. Like Mr. Clair's son showing up in England with those oil men. Kidnapped all the way to England. Then the best land is turned to oil so we can't even feed the animals or us."

So the women went to work too and Josie sat up alternate nights with Will out on the porch, hiding the pistol in the folds of her skirt while James was riding patrol. But here and there a body would turn up, in the lake or hidden beneath leaves the wind blew away.

In the white fire of noon, the air slowed. It was a beautiful summer day and in the light there were no hints of any danger.

Will's brothers had gone to the rodeo where they rode bareback broncs and roped cattle to earn extra cash. Last year Dwight paid a two-dollar entry fee and won the $40 bull-riding purse. Ben lost more money than he made gambling on the horse races and he accused the horses of being cursed and went to pick up the dirt from their tracks, while the white men called him a "crazy Indian." But he had known all the horses and each one's flair for speed and sure enough in the shadows of the horses, he found lizards with new green tails. He threw back his shoulders: "You whites are all fixers."

Will thought of this as he stood beside Shorty, the black horse. The horse was motionless with slow dark eyes. Mr. Johns had been training Shorty all spring and summer and the horse was proud as a nighthawk.

Will's hair was slicked back. It was as sleek as the horse. He thought how Shorty was like silver and not a skittish bone in his body. He'd ride that beautiful black horse to the rodeo and sit straight like his father and be proud of the way his shirt sleeves billowed in the wind. He'd keep the mighty energy of the horse reined in just enough to pull back the wide strong neck like a show horse.

He put the bit in its mouth, the red wool blanket on the back of the horse, and led him outside the fence. The horse was quiet and passive even after Will's weight was on him. "Gittup!" Will hit him with his heels and tightened his knees.

The black horse stood there a moment, then he was like a fire going through straw, burning and moving all at once. He turned in circles while Will leaned forward to hold on, his legs without stirrups unable to hold the horse's body.

It was a delirious sparring match for the black horse, raised to be invisible in the dark, trained to James Johns's body, hypnotized by words to know all the stories of humans, even those of a boy's pride and vanity.

Will tried to run Shorty into the trees to slow him down, but the black horse cut a tight corner and veered off again before Will could leap down or grab a branch. The branches slapped at Will until he was forced to bury his face deep into the black mane and wait for the horse to tire, but Lord, the entire earth would be threadbare before one muscle on that animal wore out, and Will tasted blood on his lips. The horse was the wind or a river and Will was only a leaf on its current.

Will didn't know how long his father had watched before riding up alongside Shorty and stopping the wild horse from his dance of fire. Shorty's fur was damp and smelling like hay and Will and the red blanket slid down.

"I told you, stay away from that horse," said Mr. Johns and he whipped a leather strap against Will's leg while Shorty snorted and whinnied and stamped the ground like he was laughing.

Later, the rodeo still going, Will sat over his schoolbook and thought what his act might have cost. He hadn't known his father was guarding their house in the daylight or that the Willis house had been dynamited the day before.

It was not that Will was down at the heels about missing the rodeo or being humiliated by that horse but that he was learning too young about fear and hatred. The Indians thereabouts had just begun to learn not to trust the agents. They were slow to understand that white people speak words they don't mean when they want land or money, that when they say life, what they mean is death. The more Indians that began to understand this, the more deaths there were. The gods had lost their ways and all Will knew was that the midnight cries of birds terrified him and he woke sweating in the night when the riders passed by.

It was an unseasonably cool year and the pasture was not rich and green, so one morning Mr. Johns woke the boys early to drive their uncle's cattle and their own few head to better pasture.

They'd been under surveillance by the Uncle Sam officers, especially now that Dwight was about to turn the age when he could sign over the lands the oil company already held down by the river valley, so Ben and Josie remained at the place with an uncle while Will rode along with the heavy plodding cattle.

Will looked tired with dark circles under his eyes. In the saddle he was slumped as if he were sleeping in the few warm rays of sun. They rode past the Hastings' place and he thought about the old woman sitting in the hospital wrapped in a shawl of hope.

All the deaths had taken their toll on everyone. Mr. Johns had been thinking of moving the family out and letting the agents and crooks and leasers have all the allotment land, but each night when the darkness fell, after he vowed to himself that they would leave, he found himself again saddling Shorty or sitting at the door listening for strangers. And Josie said she wouldn't leave any place again and what would become of the boys moving on all the time to escape the Uncle Sam agents.

James Johns rode up alongside Will and touched the side of the boy's knee. And felt amazed at the life and warmth· of him. Will felt a promise in the heavy hand.

"Son, I was just wondering if you'd like to ride Shorty."

That damn horse laughed. Will saw it. That horse laughed, and the cattle moved a little quicker toward the pasture and the clouds brightened and there were flowers in the fields.

Tags

Linda Hogan

Linda Hogan is a Chickasaw. She is the author of Calling Myself Home, Eclipse, and Seeing Through the Sun. "That Horse" is included in a collection by that title from Acoma Press in New Mexico. She has recently moved to Minneapolis where she teaches in the American studies and American Indian studies program at the University of Minnesota. (1985)