Future Light or Feu-Follet?

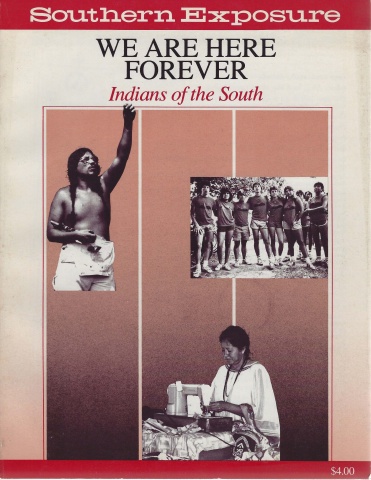

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 13 No. 6, "We Are Here Forever: Indians of the South." Find more from that issue here.

On July 18, 1985, the United Houma Nation, Inc., of Louisiana filed a petition with the United States Department of the Interior seeking federal acknowledgement of their status as an "Indian tribe." The petition is a 437- page document composed primarily of historical and cultural information, tribal governing articles, and membership lists. All this information is aimed at helping to prove the Houma are who they say they are - American Indians.

It is ironic that people who were recognized as a group by French explorers as early as 1682 now have to "prove" their identity to a government scarcely 200 years old. To non-Indians, the concept of federal recognition may seem perplexing; to many Indians, it is insulting.

Essentially, federal recognition is the establishment of a legal relationship between the U.S. government and an Indian tribe. This relationship imposes reciprocal responsibilities and obligations on both the government and the tribe. Although the tribe subjects itself to the authority of Congress, its status as "recognized" makes it eligible to apply for federal benefits and services. Federal recognition does not mean an automatic entitlement to government funds. The current regulations state that federally recognized tribes may be eligible for benefits and services although "requests for appropriations shall follow a determination of the needs of the newly recognized tribes" (emphasis added).

It was not until 1977 that the federal government began developing formal recognition procedures in response to an increase in the number of petitions received by the Bureau of lndian Affairs (BIA). This is the bureau within the Department of the Interior which administers and oversees most programs for federally recognized tribes. Seven criteria must be met. The first three elements are critical and usually the most difficult to meet. The tribe must prove:

1. historical identification on a substantially continuous basis as an American Indian tribe. This can be proven by identification as American Indians by: foreign governments; federal, state, and local authorities; federally recognized tribes or national Indian organizations; official records; newspapers; and scholars of history and anthropology;

2. habitation of a specific area by a substantial portion of the petitioning group, where members must be descendants of the Indian tribe that historically occupied that specific area; and

3. evidence of tribal political influence over the members, exercised throughout history and to the present.

The other four elements, while important, are relatively easier to establish. The tribe must provide:

4. copies of the group's governing documents,

5. a membership list,

6. a statement of proof that the membership is composed principally of people not members of other federally recognized tribes, and

7. proof that the group is not the subject of congressional legislation expressly terminating or prohibiting the federal relationship.

The evidence presented in the Houma petition to meet these criteria relies primarily upon the work of Jan Curry-Roper, Greg Bowman, and Jack Campisi. Both Curry-Roper's and Bowman's work was sponsored by the Mennonite Central Committee. Campisi's work with the Houma was in association with the Native American Rights Fund, based in Washington, DC, which represents the Houma in their petition efforts.

Curry-Roper traces historical references to the Houma to 1682. In that year, the French explorer LaSalle took note of the tribe's settlement located near present-day Angola, Louisiana. Curry-Roper documents encounters between the Houma and numerous other French explorers and officials including: Iberville (1699), Bienville (1700), the Jesuit missionary Gravier (early 1700s), and French governor del'Espinot (1764). The Houma coexisted peacefully with the French for nearly a century and, as a result, entered into no written treaties with them.

In 1763 England and Spain divided sovereignty over the Mississippi River,,_ Valley with England claiming lands east of the river and Spain claiming lands into the west. The Houma had contact with the leaders and representatives of both governments and were recognized as a distinct Indian tribe. Curry-Roper notes that the Houma visited English Major Robert Farmer in 1765 and that he gave them gifts. In 1771 British Indian agent John Thomas received an eagle tail feather from the Houma as a pledge of peace. In the 1780s British officer Thomas Hutchins made note of the Houma's existence near the Chitimacha Fork. The Houma's relationship with the English was not as amiable as that with either the French or Spanish. Again, as with the French, the Houma did not enter into any formal treaties with the English.

Curry-Roper presents evidence of contact between the Houma and the Spanish beginning around 1769. Indian nations living within 60 miles of New Orleans were invited by Spanish Governor O'Reilly to attend a meeting. Nine tribes attended, including the Houma. Houma oral history claims that the Spanish government gave the tribe substantial acreage near the present-day site of the town called Houma. Written evidence of this transaction is lacking, but Curry-Roper argues that Spanish Indian policy, which generally recognized tribal rights to possession of their lands, tends to support the Houma's claim.

Contact between the Houma and officials of the United States government, which had acquired the Louisiana Territory in 1803, is documented beginning in 1811. Governor W.C.C. Claiborne wrote of a visit paid him by the Houma chief Chac-Chouma. Claiborne acknowledged the tribe's existence and their reputation as a friendly tribe.

Favorable treatment by the United States officials was short-lived. In 1814 the Houma were denied their claim to lands given them by the Spanish. This violated the Louisiana Purchase Treaty which expressly called for honoring agreements made during Spanish rule.

The United States' failure to honor these agreements left the Houma without a secure land base. The tribe began moving to the less populated and at that time less desirable areas to the south. Houma members began purchasing tracts of land on an individual basis, largely in Terrebonne and Lafourche parishes.

Tribal leadership became decentralized as Houma communities adapted to the hunting-fishing economic lifestyle of the marsh environment. Settlements sprang up along the numerous bayous that meandered through lower Terrebonne and Lafourche parishes. Each community developed one or more local leaders, which represented a shift away from the traditional single-leader system which had prevailed in the tribe as a whole. Rosalie Courteaux is usually acknowledged by Houma members today as being the last single Houma "chief' before the shift to local community leadership. Most Houma trace their ancestry to one of Courteaux's seven children.

By the time anthropologist John Swanton visited the area inhabited by the Houma in 1907, seven distinct Indian settlements were in existence. Most of these communities exist today.

Swanton's visit marked the beginning of sporadic investigations conducted by the Bureau of Indian Affairs on Louisiana's Houma tribe. Most of the officials sent by the BIA were responding to pleas for assistance by individual Houma members and concerned non-Indians. No direct action was taken as a result of these investigations.

In 1932 Louisiana Congressman Numa Montet wrote to Charles J. Rhoads, then Commissioner of Indian Affairs, inquiring about the possibility of federal assistance for the Houma particularly in the area of education. Commissioner Rhoads responded:

A main objective in the work of the Federal government for the Indian is to bring him to the point where he can stand on his own feet in whatever community his lot happens to lie . ...

Without Federal aid the Indians of Louisiana exist free of the handicaps of wardship; to impose wardship upon them would be to tum the clock backward . ... We do not believe that for the Federal government to assume jurisdiction over the Indians of Louisiana today would be any kindness to these Indians.

The commissioner's letter reflects the assimilationist ideals typical of 1930s United States Indian policy. The letter also puts forth the rather dubious proposition that wardship "handicaps" Indians. This rationale was later used by the federal government to terminate its trust relationships with other American tribes in the 1950s which was the so-called "Termination Era" of United States Indian policy.

Lack of federal assistance notwithstanding, the Houma continued to carve out a home and a living in the Louisiana marshland. The relative isolation of the group actually helped them preserve some elements of their ancestry. These included kinship settlement patterns, crafts, folklore, native treatments using medicinal herbs and their Cajun French dialect.

The group's isolation also made it very easy for unscrupulous land developers and oil company representatives to erode the Houma's land base quickly. One technique commonly used m Terrebonne Parish during the 1930s was to have Indians sign documents purporting to be mineral leases. The documents were actually quit-claim deeds which transferred ownership interests to the non-Indians. Since outsiders knew that the Houma generally were neither English-speaking nor literate, tribal members became relatively easy targets for fraudulent land conveyances. The tracts of land privately held by individual Houma at least in Terrebonne Parish, were' almost completely lost during this period.

The bitterness felt over the loss of land rights was probably second only to the Houma's frustration at being denied the right to an education. Except for a few church-operated schools in the 1930s and early '40s, the Houma had no significant opportunities for formal education. Terrebonne and Lafourche parishes both operated segregated Indian schools on a sporadic basis in the 1940s. Not until the 1953-54 school year did the parishes become consistently involved in the education of Houma children. A new Indian school was built in Dulac in Terrebonne Parish, and the Lafourche Parish school in Golden Meadow continued to operate. However, until the 1960s, the Indian public schools in both Terrebonne and Lafourche parishes went through the seventh grade only and Indians were denied access to the public high schools.

As a result of a lawsuit filed on behalf of Houma children, a Louisiana federal court in 1963 ordered the integration of the Terrebonne Parish public schools. Integration was implemented on a staggered plan beginning with the public high schools. Rita Duthu (the author's aunt) became the first Houma to graduate from an integrated public high school in 1965. She graduated seventh in a class of more than 200.

Elementary schools in Terrebonne Parish were finally integrated in 1969. In that year, the Dulac Indian School was dismantled, floated on barges up the bayou and reassembled behind the school which white students attended (Grand Caillou School). In 1969, Indian, white, and black students were finally permitted to sit in the same classroom in Terrebonne Parish public elementary schools.

The 1970s were a period of political organization for the Houma. The Houma Tribe, Inc., had already been formed, and operated out of Golden Meadow in Lafourche Parish. The Houma Alliance, Inc., was formed in April 1974 and operated out of Dulac in Terrebonne Parish. The objectives of the two groups were different. The Lafourche Parish group concentrated primarily on adult education while the Terrebonne Parish organization focused on tribal economic development. The two groups finally merged on May 12, 1979, to form the United Houma Nation, Inc., governed by a 14-member council representing the five Louisiana parishes with Houma populations. Council members serve -year terms with the exception of the tribal chair, who serves a four-year term.

There are 8,715 Houma Indians listed on the most current tribal record. People with one-eighth degree or more Houma Indian ancestry may be admitted as tribal members. The Houma are the largest of Louisiana's five Indian tribes, the second most populous being the Chitimachas with 520 members. The other tribes include the Tunica-Biloxi, Coushatta, and various Choctaw bands.

Most Houma are employed in either fishing or oil-related industries. Commercial fishing or "trawling" for shrimp occurs year round in the Gulf of Mexico, but it is seasonal within inland waters. Since many Houma rely on smaller boats not suited for Gulf conditions, they are subject to seasonal restrictions. Houma workers in the oil industry hold positions ranging from "roustabout" and "rough neck" to production supervisors and safety directors. Roustabouts and roughnecks perform the heavy physical labor associated with oilfield drilling and production. Recent cutbacks in oil production combined with the seasonal nature of shrimping have reduced the number of stable, year-round jobs available to the Houma.

The contemporary language of the Houma reflects their longstanding relationship with the French. Cajun French is the first language for Houma born before 1960 while English is predominant in the latest generation. The Houma Indian language, part of the Muskogean linguistic group, is long lost as a native tongue. Extensive oral histories conducted during the 1970s revealed that only a few Houma words remained in the memories of the tribe's elders.

While the Indian language of the Houma is lost, several other traditional elements remain. According to research presented in the petition for federal recognition, traditional Houma culture can be seen today in their crafts, folklore, and folk medicine. Woodcarving and basket weaving are skills preserved by several craftsmen. Antoine Billiot of Dulac is one of the most prolific, using the palmetto plant for his basket and fan weavings.

Houma folklore collected by the authors in 1978 provides several examples of oral traditions that are shared with neighboring Indian tribes. Among the Houma, the feu-follet (false light) stories are told of lights that appeared in the night and misled people into the marshes. This is similar to the Choctaw's hash-okwa hui'ga (will-a-wisp) legend. The Choctaw boh-poli or trickster character is also present in Houma folklore, known by the French name loutain.

The traiteurs (treaters) play an important role in Houma folk medicine. Traiteurs may use both Christian and herbal treatments for the cure of the ill. While some of the herbal treatments may have been influenced by Europeans, the majority are of native origin.

Contemporary Houma culture is heavily influenced by Catholicism, first introduced by the French in the 1700s. In Terrebonne Parish, where some churches once barred Houma from sitting with whites, a Houma priest now leads a congregation.

The discrimination practiced in the church aisles was also practiced in restaurants, schools, and stores. Although the intensity of hostility toward Houma may gradually be decreasing, discrimination still persists.

Hostile whites use the derogatory term "sabine" to refer to the Houma. This term represents an attitude of people who refuse to acknowledge the Houma's identity as American Indians. One old Houma man explained the use of the word. "It's just that people had a word thay called the Indians, 'sabines.' It meant that the Indians were nothing. They weren't anything at all. That's the way they [non-Indians] wanted it. There were a lot of people who called me a sabine."

Tribal Chairman Kirby Verret feels that white hostility toward Houma only intensified their sense of Indian identity. "They say we are not Indians but look how they treated us. I say if we are not Indians then they made us Indians by the way they treated us."

The present drive for federal recognition is aimed, in part, at rectifying the effects of past discrimination. To anticipate what the impact of federal recognition might be, the Houma may look to other federally recognized tribes within the state.

The three federally recognized Louisiana tribes are the Chitirnacha, the Coushatta, and the Tunica-Biloxi. The Chitimacha have been recognized since the 1800s; the Coushatta did not receive federal recognition until 1973. The Tunica-Biloxi were the last Louisiana tribe to receive federal recognition. Eli Barbry, leader of the Tunica-Biloxi in the 1930s, went to Washington seeking recognition for his people. Forty years later, in 1974, a formal petition was filed during Joseph Pierite's tenure as tribal chairman. Meeting the strict genealogy requirements proved a major obstacle in filing the petition. In 1981 when recognition finally came, the new tribal chairman Earl Barbry witnessed the fruition of his grandfather's efforts. The Tunica-Biloxi have 230 members, according to the last roll taken in 1978. Forty-five percent of the Tunica-Biloxi live outside the state of Louisiana. The tribe is located in the center of the state, near Marksville, where it owns 134 acres.

Before the Tunica-Biloxi's federal recognition in 1981, the only federal program provided for the tribe was the Comprehensive Employment Training Act (CETA). With recognition, the Tunica-Biloxi were able to obtain over a million dollars in various program funds within the first year and a half of federal recognition.

One of the first and most essential programs made available through federal recognition was training and funding for the tribal government. Prior to recognition, members of the seven-member council served strictly on a voluntary basis - with no salaries and little or no training in the area of applying for federal and other grants. In April 1985, a new tribal center was dedicated. Working within the facility are 10 employees including Tribal Chairman Barbry and two other council members. The tribal government has stabilized as a result of staff training in the areas of planning and finance.

With funds from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the Tunica-Biloxi have built 11 new homes since 1983. The houses are titled to individual Tunica-Biloxi after the tribal government reviews applications. A title reverts to the tribe upon the individual's relocation or death.

The Indian Health Service provides health care to members living in the tribe's designated service areas of Rapides and Avoyelles parishes. The health program provides funds for an individual's medical costs after his or her own insurance coverage has been exhausted. A meals program for the elderly is administered by the tribe.

Barbry sees the future of the Tunica-Biloxi tribe being built on the development of Indian-owned enterprises rather than relying strictly on government aid. The Bureau of Indian Affairs Guaranteed Loan Program guaranteeing up to 90 percent of a loan amount offers potential for development of lndian-owned businesses. Barbry reports that the tribe is working on a two-million-dollar loan package to purchase a pecan-shelling plant in the area. He estimates that the plant ill employ 110 people - Indian and non-Indian. "The community has been very supportive. We hope that we can use the profits from our own business to provide services to our members living outside our service area," he says.

The Tunica-Biloxi have considered developing other businesses using the BIA loan program, including catfish plant and a food-processing plant. The catfish plant could provide jobs for 60 people directly with another 1,200 related positions in farming and shipping.

The Tunica-Biloxi have also been approached by less desirable developers, according to Barbry. Bingo games are big business in Louisiana and one management company promised millions of dollars in investments to develop bingo under the tribe's sponsorship. The tribe declined the offer.

Approximately 100 miles to the south of the Tunica-Biloxi live the Chitimacha. The tribe is based on the ony Indian reservation in the state, near the town of Charenton. There are 520 Chitimacha today, with 220 living the 283-acre reservation.

The only major service offered by e tribe before the 1970s was the Chitimacha Indian School. The school, for grades one through eight, been in operation from 1934 to the present. After the eighth grade, Chitamacha youth attend the local high school.

In the early 1970s things began to change, according to current tribal an Larry Burgess. Tribal election policies and procedures were developed with training from the BIA. Burgess identifies this process as a first step in attracting government money: "We had to put all the systems place first ... to learn to be accountable."

A tribal center was built in 1973 and there are currently plans to build a larger center. The tribal center employs 24 full-time staff. A Job Training Partnership Act (JTPA) program works to train and place tribal members in community jobs. The Chitimacha are able to provide an extensive health program for their members living within St. Mary's Parish. It includes transportation to and from medical care, financial assistance, and substance abuse and mental health counseling, as well as a referral service.

Various housing programs are also available. Seven new houses have been built on the· reservation. Some existing homes have been equipped with handrails and ceiling fans as part of a home improvement program. In June 1985 the Chitimacha Housing Authority was recognized by HUD, thus opening the door for the tribe to apply independently for other department programs.

Despite the strength of the Chitimacha's elementary education program, the tribe is able to provide little support for college education. As with the other two federally recognized tribes in the state, the Chitimacha offer assistance to students applying for BIA education funds. But these funds are very limited and have decreased in recent years. Another source of college financial assistance for Louisiana Indians is available through their association with United Southeastern Tribes, which distributes four separate $500 grants to students each year from among the pool of needy applicants.

Like the Tunica-Biloxi, the Chitimacha may apply for loans through the BIA guaranteed loan program. The tribe now provides technical assistance to individual members who seek loans to establish small businesses. In addition, the Chitimacha have considered developing a new pipe-fabricating business in the port of St. Mary.

None of Louisiana's federally recognized tribes currently operates its own tribal police force or court system. However, Chitimacha chairman Burgess indicates that funding approved in the summer of 1985 provides for a tribal police force which should help resolve law enforcement problems, particularly for crimes committed on the reservation where other local law officials have no jurisdiction. Also in effect since March 28, 1985, is the Louisiana Court of Indian Offenses, a judicial body created to serve the Coushatta and other Louisiana tribes who resolve to submit to its jurisdiction. Legislative history of the act creating this body is sparse and does not indicate how the court is composed or what its jurisdiction might be. Tribal chairman Larry Burgess notes that services must address the needs of individuals as well as the tribe: "If we cease to respond to the needs of the people on an individual basis or as a whole, then we don't need a tribal government."

Unity within and among tribes is essential to the progress of all Louisiana Indians. Tunica-Biloxi leader Earl Barbry stresses the importance of Indian unity. He says, "For the longest time tribes in Louisiana were divided, fighting against each other. With all the fighting, we can't make any progress. Now it's getting better."

Several organizations act to promote unity and improve communication among Louisiana tribes. The Inter-Tribal Council (ITC) was established in 1975 "as an effort in Indian self-determination," that is, Indians governing Indian programs. The ITC currently represents the five major Louisiana tribes: the Houma, Tunica-Biloxi, Coushatta, Chitimacha, and the Jena Band of Choctaw. The ITC assists in administration of statewide services including the Job Training Partnership Act and programs for the elderly.

The Institute for Indian Development (IID) in Louisiana was created in 1982 to provide technical assistance to the tribes. It includes the five tribes listed above, as well as the three smaller Choctaw bands located in the state: the Apache Choctaw, the Clifton Choctaw, and the Louisiana Band of Choctaw. The tribal chairman of each Louisiana tribe sits on the board of the IID.

When the Houma considered filing or federal recognition, they were unare of its advantages and disadvantages. Longtime tribal leader Helen Gindrat recalls that Coushatta leader Ernest Sickey "told us about some of the benefits but then reminded us that we'd have to compete with others on a federal level. He encouraged us to 'go for it.'"

Now that the petition for recognition has been filed, the Houma still have some questions as to exactly what federal recognition will mean if it should become a reality. Unfortunately, a great deal of misinformation is being exchanged in Houma circles. Perhaps the most common misconception is the belief that federal recognition will automatically translate into dollars for each individual Houma member. At the August 1985 Houma tribal council meeting, one council person repeatedly referred to the "settlement" money the people would receive while other individuals raised questions about possible land claims.

The belief that federal recognition means money in the people's pockets can distort the tribe's goals and inflate its membership numbers. Earl Barbry of the Tunica-Biloxi remembers how many non-Indians scrambled to get a piece of the pie once federal recognition was announced: "If we'd have put everybody on our rolls who claimed to be Tunica-Biloxi, we'd have had more Indians than the Navajos!"

The belief that federal recognition will automatically mean the return of land to the Houma tribe is also inaccurate. Land claims must be proved like any other claims. A federal statute, the Indian Non-Intercourse Act of 1790, invalidates all transfers of Indian land made without the federal government's prior consent. Federal recognition would give the Houma legal standing to file suit for land they claim was fraudulently taken from them, but it would not prove their case.

During the next five years, it is critical that the Houma tribe work to provide accurate information both to its membership along the bayous and to the bureaucrats in Washington. Helen Gindrat notes, "The petition process depends on how much information they [BIA] need and how fast we can get it to them. If Washington picks up the phone and there's no one here to answer, the process comes to a stop." She anticipates that due to limited staff the Houma may have some difficulty responding to requests for further information from Washington.

The priorities identified by the Houma for the future include health care, education, and housing- though not necessarily in that order. Chairman Kirby Verret stresses the importance of education to Houma youth:

We didn't have the opportunities for education in the past. If you wanted to get a high school diploma, you had to leave the bayou. Now we've got a chance at education and we've got to encourage the kids to go as far as they can. If we're going to compete with the white man, we've got to get the same tools. That means education.

Helen Gindrat points to the importance of health and housing: "If people can take care of their health and live in a decent house, then they can go on to other things." One of the "other things" Gindrat identifies is economic development. The Houma's potential for economic development may be strengthened through the BIA loan program available to federally recognized tribes. "We need to have people with business expertise, to identify what is practical and what's not," says Gindrat. The Houma considered development of a fishing cooperative in the early '70s. The project did not get off the ground, according to one Houma fisherman, because people were reluctant to risk some of their personal savings. "Everybody liked the idea but when it came time to put up some money, a lot of people had to back out."

A recent article in a New Orleans business newspaper reported that Louisiana was first in the nation in total seafood production by weight and second in seafood dollar value. Fortynine percent of the nation's seafood is harvested in Louisiana waters, according to the article. However, 84 percent of it is processed out of state and returned to Louisiana as someone else's product. One Louisiana official was quoted as saying that for every dollar of raw product, processing increases the dollar revenue by five to seven dollars. For the Houma, the significance of these facts and figures is that seafood processing is an industry the tribe may want to consider developing. And economic development on that scale would be virtually impossible without the federally guaranteed loan program available to federally recognized tribes.

What federal recognition may eventually mean to the Houma nation remains to be seen. The Houma clearly satisfy the requirements for federal recognition and should be acknowledged by the United States government. For the Houma, it will be important to keep federal recognition in perspective. Since an actual determination by the Department of the Interior and the BIA on the Houma's status may be years down the road, the Houma cannot afford to sit still and patiently place their collective eggs in the federal recognition basket. They must continue to do what they are currently doing - seeking out and developing other sources of support both from within the tribe and outside of it. Federal recognition is a realistic approach to helping the Houma become a self-determining tribe. It is not, however, a cure-all for the Houma's present-day problems.

The positive aspects of recognition are that it could aid in making economic development programs a reality. The seafood processing industry noted above offers tremendous potential, but without adequate capital or financial backing it is not likely to get very far. Recognition could stimulate the opportunities for educational advancement and vocational training. Both areas would help make Houma members truly competitive in today's job market.

One negative aspect of recognition is the possibility that the tribe may lose its resourcefulness in finding ways to "get along" if it develops the habit of looking toward Washington for all its needs. The danger is that Washington could, at any time, turn off the money supply. After all, only three decades ago the official United States Indian policy was to terminate trust relationships with all American Indian tribes. Further, the Houma should be aware that the United States has not always acted towards its "wards" in a manner characteristic of a "guardian" or trustee.

A recent United States Supreme Court case seems to indicate that, in some instances, the Indian tribes have no recourse against the federal government for breaches of the trust relationship. The case involved a suit by the Quinalt tribe in Washington state against the United States for money damages arising out of claimed mismanagement of forested reservation lands. The lands were held in trust by the United States for the "use and benefit of the Indian tribe." The Supreme Court in 1980 ruled that the tribe could not recover money damages for these actions since there existed only a limited trust relationship between the government and the tribe.

The point is that United States policy towards American Indians is often unclear and unpredictable. The Houma would be wise to recognize this before entering the "ward-guardian" relationship.

Why then should the tribe even bother with federal recognition if federal Indian policy is so unstable and the government's trustee actions (or inactions) can go unchecked? The answer is relatively simple: the potential advantages of federal recognition outweigh the disadvantages. Recognition is an opportunity to produce positive changes in the tribe's overall development. But if misconceptions about federal recognition predominate and people's expectations become unreasonable, federal recognition could become like the feu-follet of Houma folklore, leading the unwary deeper into the swamp.

Tags

Bruce Duthu

Bruce Duthu is a Houma Indian from Dulac, Louisiana, who practices law in New Orleans. Hilde Ojibway is a member of the Sault Ste. Marie Band of Chippewa and is from Lansing, Michigan. Since 1978 they have been collecting Houma folklore and helping with the tribe's efforts to secure federal recognition. (1985)

Hilde Ojibway

Bruce Duthu is a Houma Indian from Dulac, Louisiana, who practices law in New Orleans. Hilde Ojibway is a member of the Sault Ste. Marie Band of Chippewa and is from Lansing, Michigan. Since 1978 they have been collecting Houma folklore and helping with the tribe's efforts to secure federal recognition. (1985)