This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 13 No. 6, "We Are Here Forever: Indians of the South." Find more from that issue here.

During the eighteenth century, the Creek Nation attempted to placate the United States government, serving as soldiers in defense of landholdings in Georgia and even cooperating with the planter economy that flourished in the coastal states by returning fugitive slaves. But the colonists were deter- mined to drive the Creeks out of the coveted lands of the Southeast. By the 1750s, the Creek nation had become two separate nations. The Seminole, a Creek word meaning fugitive, runaway, or rebel had joined the remaining native peoples in the then-Spanish territory of Florida. They were joined by fugitive slaves, and together they established a formidable army. Beginning in 1812, The U.S. government sent waves of soldiers to uproot the budding nation from Florida. They were unsuccessful. During the Removal Era, the government did succeed in deporting most of the Seminole to Oklahoma, but a remnant remained, refusing to yield. The Seminole are proud of their history of resistance. The price they paid has been impoverishment.

In May 1985, James Billie, chair of the tribal council of the Seminole Tribe of Florida, delivered the following address to the Florida State Senate Finance, Taxation and Claims Committee about Governor Bob Graham's demand that tribally owned smoke shops charge the 21-cent state sales tax on cigarette sales to non-Indians. Claiming that the state is losing $15 million in tax revenue from the smoke shop sales, committee chair Bob Crawford (D-Winter Haven) called the tax break granted the tribe by the state in 1978 a "highly inefficient" way to "help" the Indians. The committee voted to make no changes.

The Seminole, it seems, have aroused the ire of the state and many of Florida's white citizens by turning a profit with cigarette sales and the operation of bingo parlors, two enterprises which net $8 million annually. Just 28 years ago the Seminole of Florida, who claim the distinction of being the only tribe that the U.S. Army was unable to defeat, were granted tribal sovereignty, a legal status which exempts them from state statutes and regulations, other than criminal. They are, in effect, a nation.

The Seminole defend their money-making activities based on their increasing financial independence and the overwhelming needs within their nation for essentials like health care, housing, and education. Further, they are keenly aware that their sovereign status is under attack through efforts to sway public opinion against them by making the issue appear to be a moral one. Cries of potential corruption permeate discussions about the huge sums of money earned by the tribe, and Florida journalists and politicians openly question the ability of the Indians to manage their own affairs without the aid of state regulations.

The Seminole's stance is echoed throughout North America as state attempts at regulation threaten to erode Indian efforts at self-governance and self-sufficiency. James Billie, however, does not dwell over long on the legal issue of sovereignty, but emphasizes the pressing need to address the economic and spiritual needs of the people of the Seminole nation.

Mr. Chairman and distinguished members of this committee, allow me to thank you for this opportunity to make this presentation today on this issue of great importance to the 1,600 members of the Seminole Tribe of Florida.

In these times when this great deliberative body is faced with such major issues as the protection of coastIands, the future of higher education, and, most importantly, the management of our state's growth into the next century, I am most appreciative of your commitment of valuable time today to consider the impact of the proposed legislation on the oldest, yet smallest, of Florida's constituencies - one that in numbers represents less than four days of the population growth of this state that you are striving to manage this session.

I am James Billie, chairman of the Seminole Tribe of Florida. I have been elected and reelected by the members of the Seminole Nation and I have seen my responsibility as chairman to provide the necessary leadership, like you, to prepare my constituents for the twenty-first century. I'll admit to you that we both have a long way to go.

In addition to my own testimony today, I have brought with me some members of my tribe who I believe will present you with perspectives beyond what I am able to articulate: Judy Baker, who is a successful businesswoman; Tina Osceola, a young woman who has a dream of attending law school; Elsie Jean Bowers, who runs our health department; Betty Mae Jumper, who was our first and only tribal chairwoman; our housing director, Eloise Osceola; and Winifred Tiger, the tribal director of education.

I could speak today to you about the history of the Seminole Tribe in Florida - our dealings with the federal government and our dealings with the territorial and state governments of Florida during this century and the two before it. But you have read the history books and I'm sure you are familiar with the policies of deceit and the wars our grandparents fought, including the longest Indian war the United States was ever involved in. I could speak today about the treaties broken, black slaves taken in, about families spilt into a nation divided by the geography of convenience. But I won't. It's not my intention to burden you with the sins of your ancestors. It's not my desire to play upon the white man's guilt.

What I intend to speak about today is the history of the Seminole Tribe of Florida as I personally know it; the history of my lifetime, or at least since I can remember - the modem-day development of the Seminole people from the war years on, the phases our people have gone through and are going through.

I was very fortunate in my younger years. I was forced off the reservation, as some of you probably were forced out of your homes and hometowns by our nation's commitment in Vietnam. It gave me an education beyond the reservation that helped me develop a perspective that is difficult to describe - because unlike you, I was a product of another third world, believe it or not, a third world, totally within the boundaries of the United States. The transition to Southeast Asia was not difficult for me, but certainly the return home was.

The only way I can describe my perception of the attitudes of my people upon my return, or certainly a large percentage of them, is a Seminole word Hun Tashuk Teek. The closest definition I could find in Webster's Collegiate for this word is apathy: lack of interest, indifference, lack of desire to set or achieve a goal. This state of mind is still apparent among some of my constituents, but - to quote the greatest civil rights leader of our time - "I have a dream!" And each man, woman, and child of my tribe shares that dream. My people are moving toward that dream and the revenue to the Seminole Tribe that we are debating today is as important a component of the fulfillment of that dream as any I have to give you.

As I indicated, apathy, in the modern perspective of the Seminole Tribe, has been the prevailing attitude. Apathy brings despair. Despair brings dependence, dependence upon the unnatural. I shouldn't have to tell you about the alcohol and drug problems among my people. I have a dream that these won't be issues in our next century - or better yet, decade. But as leader, chief, chairman of my people, I must address the problems as I see them.

When I campaigned for the privilege to lead the Seminole Tribe, I saw many problems that related to this Hun Tashuk Teek. The most dangerous problem I saw was drugs, in the sense of abuse, but as much so in the sense that it was an easy opportunity to elevate oneself to the values of the non-Indian world - an easy way to get rich, if you will. Upon election I came to the state of Florida and asked you to build me a police force. You didn't have the funds. Cigarette sales gave us the funds to build a police force and while I can't say we've won our war on drugs, I can say that, like you, we've made significant strides. Our police have seized planes, made significant seizures, and continue to make drugs and druggies an unwelcome part of our reservation. In doing so, we prevent this poison from paralyzing not only our youth, but yours as well.

Hun Tashuk Teek is becoming an attitude of our past in other ways, as well. Selling beads and wrestling alligators, while still an important part of our economy, are not the pinnacle of our dreams for economic development. Our children are developing role models. In this very room sits a full-blooded Seminole Indian who is a member of the Florida Bar - an incredible achievement when we consider that a little more than 20 years ago we were barred from the public school systems in this state. We have two members of the tribe now with master's degrees, 10 more who are college graduates, 15 with associate degrees, a registered nurse, and three paralegals. We have 10 students enrolled in college now and 51 more who want to attend.

Before we sold cigarettes, our high school drop out rate was 68 percent. Yes, I said 68 percent. In our entire tribe in 1977, before we sold tobacco, less than 10 percent of our entire tribe were high school graduates. I have a dream that my children and the children of my tribe will not ask if they can go to college, but will ask the same questions your kids ask you: should I go to Harvard or Yale, or Florida or Florida State, or FIU or FAU, Broward Community College or the University of Miami. The revenue from our tribal taxation of cigarettes is making that not only possible, but reality.

There's another term I wanted to discuss this afternoon that I couldn't find in Webster’s Collegiate, but I know each and every one of you has either heard it or used it in your regulatory oversight of banking and insurance in Florida. The term is "redlining." [Redlining is a practice by which banks mark off - redline - certain areas on the map; they refuse to make mortgage or business loans within this territory.] Perhaps my use of this term will shed new light on its origins. The term "redlining" describes, better than any other term I have heard, the entire original purpose of the reservation system of lndian tribes in this country. It certainly did and has worked to our disadvantage. I would encourage those of you who sit on the commerce committee to ask of the banks and insurance companies that you regulate, how many loans or policies are sold on our reservations. The original purpose of reservations, and I must defy anyone who challenges me on this, was not to protect Indians but to separate them, to prevent our assimilation, to disallow equality.

But alas, the reservation system is our economic boom of the last six years, I'll admit. Not, however, without battles in the courts and on other fronts such as this one. We are catching up to the rest of society but we still have a long way to go.

I've been asked to provide the state with figures on where the money from our cigarette sales goes. I'm pleased to have the opportunity to tell you.

Every man, woman, and child who is a member of the Seminole Indian Tribe receives a dividend, quarterly, from our business interests: cigarette sales, bingo, cattle production, land leases, etc. Remember, the federal government required us to organize as a corporation in 1957, and my constituents are stockholders in that corporation.

Some years ago, the state was kind enough to allow our children to attend the public schools in the counties where we live. This was great in Hollywood and tolerable at our reservations in Brighton and Immokalee and Tampa. The middle school and high school students on the Big Cypress Reservation can tolerate, as well, an hour-and-a-half drive to school in Clewiston. But we don't ask this of our preschoolers and primaries. Cigarette revenues help support our own elementary school at Big Cypress. Since our ability to sell cigarettes came about in 1978 the quality of life has improved dramatically for my people, my constituents, [who] even though [they are] a small portion of the whole of this state, [are] your constituents, too.

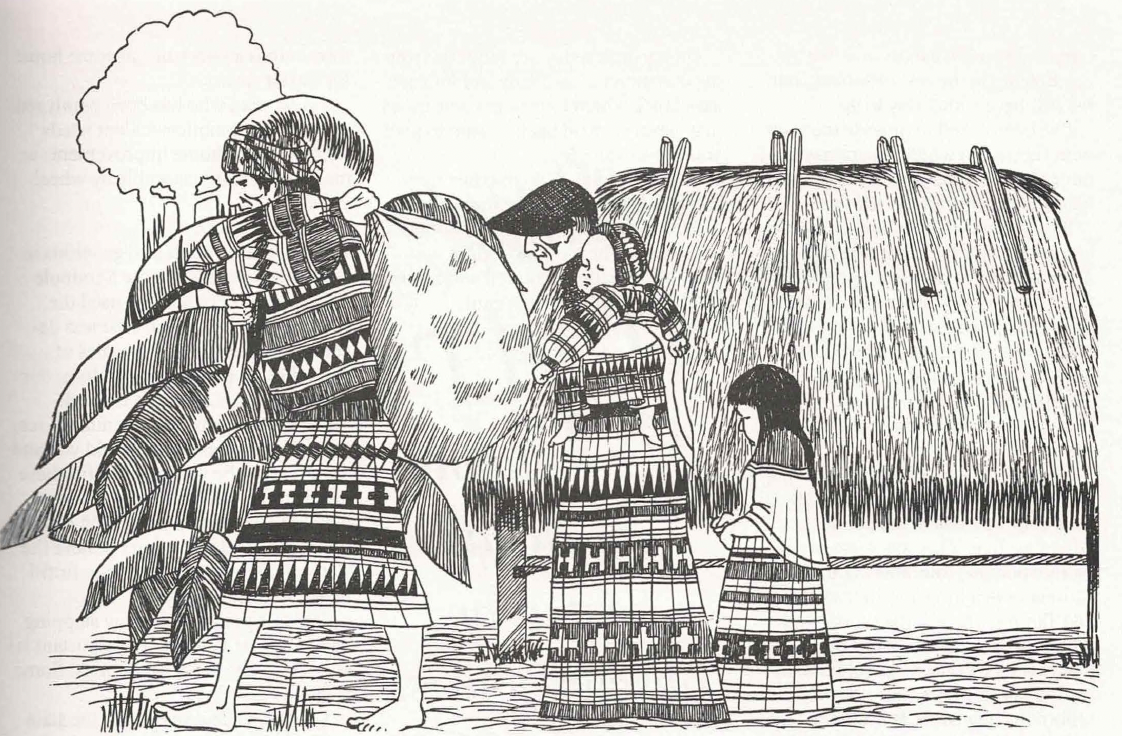

In those six years our employment rate has increased by 20 percent, while our population has grown by more than 25 percent. We have built more than 250 new housing units since 1977 and reduced substandard housing by 75 percent. You should know that I and many of my people came into this world living in chickees [grass and bamboo huts].

This redlining which kept us an obscure tourist attraction, selling beads and wrestling alligators for so many years, is now working to our advantage - it has given us a dream.

Look at our budgets. In 1957, when we organized to comply with the Bureau of Indian Affairs standards, our entire tribal budget was $50,000. Even with federal grants, which are becoming more and more scarce today, prior to cigarette sales our budget in 1977 was less than $500,000. Now it tops $7 million.

On my desk today are requests from my constituents for loans and for cash assistance which I know in some cases may never be paid back. I want to give you a few examples:

• A man wants to go into business for himself. He has a dream. He's conquered the apathy, but the redlining still exists. The bank won't talk with him. He asks if my council and I will stake him to buy enough cattle to start a herd. Cigarette money makes it possible for us to do that.

• An unmarried mother of four asks the council for $300 to buy her children new clothing for school.

• An old woman asks for $1,600 to have cataract surgery so she can see again.

• A man whose son is attending Brigham Young University asks for travel fund so his son can come home for Easter recess

• A woman who has been paralyzed from an automobile accident needs $600 worth of home improvements to make her house accessible by wheelchair.

And the list goes on.

You see, rich aunts and generous in-laws are scarce among the Seminole Tribe and our council has used the revenue from our tribal business development, including our sales of cigarettes, to parent our children, our tribal members, who are in need.

If you take away our revenue source, our self-determination, would you and the governor be willing to fulfill these basic human needs? And if you were, how long would you be willing to continue that handout? I don't believe the state could or would be able to fulfill these needs I describe.

One last point prior to my stepping back for your vote on this important issue. The issue is not all dreams! Some is fact.

Less than a few years ago, the state of Florida's Department of Business Regulation came to the Seminole Tribe with a problem - a major problem that they indicated was depriving the taxpayers of this state through illegal activities millions upon millions of dollars. The problem was bootlegging of cigarettes from states which don't have high taxes on them. To assist the state in its enforcement effort toward bootlegging of cigarettes, the tribe agreed to: (1) buy from state approved distributors; (2) create and use a special stamp denoting Florida Indian cigarettes so as to allow the state to track the origin and distribution of cigarettes; (3) provide the state with knowledge of the exact numbers of sales on the Reservations; ( 4) limit to three cartons per sale; and (5) comply with Florida laws regarding enforcement of sale to those persons of legal age.

In return, the state agreed not to oppose our cigarette sales on the reservation.

Today, as in history, I find myself before you wondering if you will ever live up to the agreements you've made with my people.