"The Earth Is Us": A Case of Sacred Right

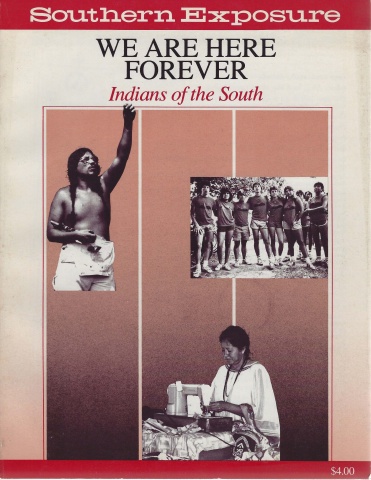

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 13 No. 6, "We Are Here Forever: Indians of the South." Find more from that issue here.

"Somewhere in this world, I want my Indian peoples to be heard. No matter how small a group they are, every one of them has the right to be who they are."

—Phillip Deere, Muskogee-Creek Medicine Man, Fourth Russell Tribunal, 1980

There is a place called Moyoane just outside of Washington, DC, on the Maryland side, that is an Indian sacred site. Many people might have seen Moyoane from the lawn at General George Washington's stately old home, Mount Vernon, as Moyoane lies just below it, a spot now containing some 20 acres.

Moyoane is the ancient capital or ceremonial grounds of the Piscataway Nation, the aboriginal people of the Potomac Valley, whose villages once spread over the sites of the present U.S. Congress, Supreme Court, and White House (where not long ago workers building a swimming pool found Indian remains).

There is an old, medicine-holding family of the Piscataway Nation in the immediate area of Moyoane. Their name is Tayac and they have inherited, through the generations, the "hosting" responsibility over the sacred site. There are about 100 self-recognized Piscataway people. The Tayacs are a principal or "chief-naming" family with a highly personal and religious intensity about the sacredness of Moyoane.

"Moyoane is what we have left," said Chief Billy Red wing Tayac, 50, who remembers coming to Moyoane as a boy. Billy's father, Chief Turkey Tayac, an Indian elder of renown before his death in 1978, held religious ceremonies at Moyoane since early in this century. "We [the Piscataways] were forced, in one way or another, to give up almost all our land," Chief Tayac said. "But we never gave up Moyoane."

Chief Tayac can give a comprehensive history of the progressive loss of land endured by the once 12,000- strong Piscataway Nation. He can recount the way the "Southern gentry from colonial times on parceled out Piscataway land," how "English-type manors and halls became the Southern plantation," how "everything, a man's wealth was measured in cotton," and how Indian generations were scattered throughout the East Coast so that "many are only now coming back out to their Indian identity, or the idea I like, 'de-Angloizing.' "

As with so many Indian groups, the Piscataways were dispossessed of most of their territory within the century of their contact with European immigrants. The fact that they had never negotiated treaties directly with the U.S., only with the British, left them without legal recourse in the new republic and their involvement in the Tecumseh wars and later the Underground Railroad brought them the enmity of Southern white society. According to Chief Tayac, the Piscataway people helped black slaves escape the South in the mid-1800s.

"Most of our people were beaten down. They felt as a conquered people. Many didn't want to identify as Indians. They didn't want to participate as Indians. You need to understand the pervasive racist mentality to appreciate what I tell you. It was: if you're not white, you are not a human being. Over the years, many Indians gave up being Indian, started saying they were Italian, or Arab.

"It was that 'White Gentry' mentality. I can remember it just as a child, they treated everybody else as a sort of inferior. They stole the land from the Indian people and brought blacks over here and made plantations. They couldn't get the Indians to work as slaves for some reason. Indians died or ran or fought. The white person at that time saw the black person as a farm animal, but he saw Indians as wild animals. They had to get rid of them, because they couldn't convert the Indians to slaves. So what they had to do, they went all the way to Africa and ripped other tribal people out of Africa - people who were black - brought them here for profit and they were slaves. They took their religions away from them, ripped them from their land. At least we Indians were on our own land."

By the tum of the present century, only a few Piscataway families attended the seasonal ceremonies at Moyoane. "later, it all fell on Turkey. He became the one to do everything, keep the ceremonies going, our spiritual relationship to our sacred place."

The Moyoane Burial Ground area had come into the hands of what Tayac calls "Southern wealth." The owners, however, recognized the Tayacs as a family with rights to their ancestors' burial grounds, especially as the numbers of ceremony participants were diminishing. "The burial ground, that's where our people are buried. That is like our Garden of Eden, our Jerusalem, our Wailing Wall. We couldn't give that up. And it is our land. We have never ceded that site. That's where we come from. That's the start of us."

The Tayac family, through Chief Turkey, are the inheritors of the Moyoane site in the Indian traditional way. "It is very important to us," ChiefTayac said, "where, how, we bury our people. This is the strongest part of our tradition we have left, that and our four sacred ceremonies, which we come together for at Moyoane, too, in their season.

"In our belief, well, we are so connected to this earth. The more we think as Indians, how the old people taught us, well, it was that this is very, very holy, how a person's remains were handled."

Moyoane is a well-documented burial site, however, and several times this century, archaeologists and others from the Smithsonian and other institutions have come to dig there. "I saw many of our remains come out of there when I was a boy. I remember how it hurt. It still hurts," Chief Tayac said. "For every step that that person took in his life, for everything he ever touched or she ever touched, every word she spoke, everything - all the blood of her body, her hair, her teeth - everything. That's all that's left of that individual. That's their remains. And nobody should have the audacity to take these persons' remains, especially if they were buried according to their beliefs, and dig them up and put them on display."

Chief Tayac said the institutions took nearly 7,000 skeletal remains from Moyoane before a member of the family that owned the site decided the 20 acres should be given to the Indians and the digging stopped. Shortly after, however, the friend died, and now two separate foundations and the National Park Service share jurisdiction over the area.

In the 1960s and '70s, political movements and religious revitalization encouraged many young Indians to go back to their cultural roots. Respect for the long-standing traditional families and vocation for the Indian spiritual ceremonies multiplied. The seasonal ceremonies at Moyoane were drawing upwards of 300 people.

Said Tayac, "Turkey knew so much that other Indians wanted to learn, and then the Indian political awareness exploded in the early 1970s. Our ceremonies started to grow again. Many Indians want to come back to our religion."

Trouble developed with the foundations and the Park Service, who expressed support for the Tayac family's use of Moyoane but balked at its use by the larger gatherings of local and regional Indians.

Once in 1973, a park ranger attempted to detain Tayac, his son Mark, and a group of Indians for gathering surface artifacts from the site and a confrontation ensued. The Indians were soon surrounded by more than a dozen patrol cars and an eight-person armored helicopter.

"I didn't want to see anyone hurt," the chief said, "but I couldn't see what right they had to regulate me on that piece of ground."

Subsequent years have brought many struggles between the Piscataway and the various authorities, some demonstrations, congressional hearings, and even a law, the breakthrough step in the fight to bury Chief Turkey in his beloved Moyoane, as he had requested on his death bed. Chief Turkey died in 1978 and was buried at Moyoane by congressional action one year later, in November 1979.

"The problem is the racist attitude," Tayac said. "My religion is real and it is tied to this site, but the society doesn't want to recognize that. They are afraid of Indians, of too many Indians, because we believe the way we do and because they are afraid of a land claim over this region. They are worried about clouded titles if we Piscataway want to press a land claim law suit under our aboriginal title here. But all we ask is that they take the 20-acre Moyoane site out of the public lands and protect it properly, not plowing parts of it like they do now, and give us private access during ceremonial times."

Chief Tayac is a serious man and his issue has national implications for hundreds of tribes across North America. Burial site conflicts are notoriously emotional in Indian communities, where there is a strong distaste for "graverobbing" as an insult and a desecration. Tayac has made his case in Congress under the basis of the 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act. The Tayacs have even traveled to Geneva to charge "attempted ethnocide" before international agencies concerned with human rights of indigenous peoples.

Chief Tayac is an affable man, calm and deliberate. I had the opportunity to visit with him at a ceremony in Moyoane years ago. It was a gathering of more than 100 people, at which a young Apache/Nahuatl man got his Indian name. Tayac feasted the people on that occasion and supervised the doings.

Among the people present were Indians from many places in North and South America. Tayac believes in pan-Indian religious ceremonies. "Nowadays, we move so much. Many Indian tribes intermarry. If there are Indians and friends in our area who care to join us, I welcome them. My feeling is, we are small numbers in our Indian groups, we should share these things."

I remember a walk with him to his father's grave. He was in good spirits that so many of the clan had turned out. A tall, round-shouldered man with two long braids hanging to his chest, Tayac wore that complete sense of belonging that gives a ceremony serene feelings. People ate and talked and told stories, some sweated in the lodge, children played and then a circle was made where the young man got his name, where he told of his people, where the chief took him into the tribe.

The four sacred colors flew from a staff near the grave, which had a well-attended look, grass worn around it, tobacco pouches. A Mohawk man who had walked along felt the moment and pulled some sweetgrass, laid it on the grave. Tayac nodded.

On the way back from the grave, the chief talked about how it was done in the old ways. Interviewed recently, he mentioned it again. "It's important that people know," he said.

Chief Billy Redwing Tayac: "Now the way it was done in those days a person had two burials. When a person died, they would many times be first put on a scaffold, in an isolated place, away from the village. A person would then be on that scaffold three or five years, time for the flesh to be taken by animals, the weather. At the end of that period, they would have a feast of the dead. There was a medicine man with extremely long fingernails. This medicine man would go over and remove all the remaining flesh from the bones. It wouldn't be much but it was all gathered, taken care of. Then the family would take the skeleton over. They would put it in a common grave in a flexed position. That's the second and final burial. Very holy."

Overlooking the burial field on that October day, surrounded by fields of corn already harvested, Chief Tayac talked about terminology. "There are a couple of words I don't like. I don't like the word prehistoric. Because prehistoric puts Indians in the time of the dinosaurs. And that is not true. The word that should be used is maybe pre-Columbian. When you use the word prehistoric people think of lndians as ancient beings similar to the caveman. That's also not a true image.

"Another phrase is 'ancient burial ground.' They call an Indian site that, where someone was buried maybe 80, 100 years ago. But there are Catholic burial sites around here where no one has been buried in that long and they are still called cemeteries.

"Bones, the word bones, too," Tayac said. "I like the word 'remains.' This is what is left of the person. It is not just bones. One has to think, what about every time that person moved their finger or held a baby, or went to pick corn, or went hunting, or tried to help his or her family. People have to understand. Every action, every ounce of hair, every ounce of blood, every ounce of bone, everything - that's all that is left of that person on this earth. Not of the spirit, but on this earth. And that is sacred as the earth is sacred. The earth is us. That's what these people don't want to understand."

He put an Indian logic to work on the why: "I've thought it out for years. And I'll tell you what the problem is. These people left their ancestors. They left their ancestors in Europe or in the case of black people, were forced to leave them in Africa. And they crossed the ocean. They broke their ties with their ancestors' earth. Their ancestors are over there in Europe, and you see those advertisements - fly PanAm to Italy, to Germany. Return to the home of your ancestors. They say: 'Walk the streets of your ancestors.' That has meaning to them. They haven't been here long enough for their ancestors' bones to be mingled in the earth here, which our ancestors' bones are, from the beginning of time. The earth is us."

Tags

Jose Barreiro

Jose Barreiro is an editor for Indigenous Press Network, a computerized news service on international Indian/Indigenous affairs. His people are Guajiro from the Camaguey region of eastern Cuba, to which he returns frequently for renewal. (1985)