Voices from the Past: This Great Profession

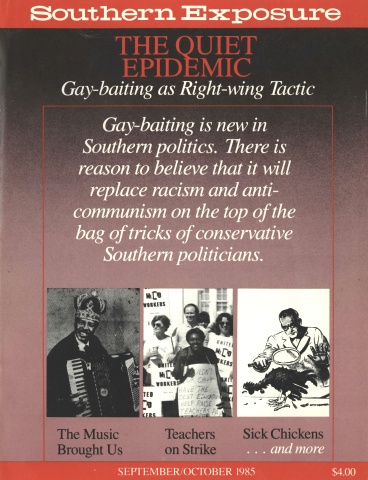

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 13 No. 5, "The Quiet Epidemic: Gay-baiting as Right-wing Tactic." Find more from that issue here.

I had from the beginners to the eighth grade, all in one room. Their ages ran from five to twenty. . . . The beginners were the most difficult of all to teach. I would bring my beginners up and teach them ABC's on the old dilapidated chart, used years and years before I came to Lonesome Valley. After I had gone over their ABC's with them, they went back to their seats and had nothing to do. They needed more attention than I could give them. Many of them fell asleep in the hot schoolroom. . . .

I knew how beginners had been taught in the Greenwood County Rural Schools in the past. I knew because I had been a beginner in this same type of school. I had been taught to read on this kind of chart, and I still knew everything on it from memory. . . .

When one of those little fellows I was trying to teach went to sleep, I let him sleep. What else was there to do? What else could I do when I was trying to hear fifty-four classes recite in six hours, give them new assignments, grade their papers? What else could I do when I had to do janitorial work, paint my [school] house, keep the toilets sanitary, the yard cleaned of splintered glass and rubbish, and try to make our school home more beautiful and more attractive than the homes the pupils lived in? . . .

[In the] morning when I got up, I was still trying to think of something to do with my beginners. I wanted to start today. . . . I went early and walked slowly along by myself and tried to think of a way. . . .

Then I started whistling. I walked along beneath the willows in the morning sun, whistling "The Needle's Eye. . . ."

"The needle's eye that does supply,

The thread that runs so true . . ."

What was the needle's eye? What was the thread that ran so true? The needle's eye, I finally came to the conclusion, was the schoolteacher. And the thread that ran so true could only be play. Play. The needle's eye that does supply the thread that runs so true. The teacher that supplied the play that ran so true? . . . Play. Play. Play that ran so true among little children, little foxes, little lambs! My beginners should play. Their work should be play. I should make them think they were playing while they learned to read, while they learned to count! That was it! I had it. Play.

When time came for my first beginners' class, I tore the big sheet from the Lawson Hardware calendar. I took the scissors from my drawer and sat in a semicircle with the class. Every eye was upon me. I cut the numbers apart, told or asked what they were, and handed them to the children. Then I cut the stiff backs of tablets into squares of approximate size. Taking ajar of paste, I pasted one number to one cardboard. Then I told the class to sit four to a seat (I had eight) and paste all the numbers and cardboard squares together.

While I went on with my other classes these children were busy. When recess came they wanted more to do — rather than go out to play. Some numbers were pasted sideways, but what did that matter? . . .

I drew objects on the board with which they were familiar — apples, cups, balls, and stick-figures of boys and girls — in groups of one, two, three, and four. When time came for the next beginners' class, I asked the children to identify the objects, first by name, which I wrote above the object, then by number, which I wrote beneath it. They were so excited they sat on the edge of the recitation bench, their bare feet tapping nervously on the floor. Then I reached for the stack of number cards and held them up asking the class to name the number. I was surprised they recognized so many.

The room was so quiet you could hear a pin fall. This was something they had never done — had never seen done — but they recognized it as an interesting way to learn. This was play.

Five years passed, during which Stuart finished high school and earned a college degree. Soon he was back in Greenwood County, the only teacher at Winston High School, a Tiber Valley school with 14 students.

Often I walked alone beside the Tiber in autumn. For there was a somberness that put me in a mood that was akin to poetry . . . Then a great idea occurred to me. It wasn't about poetry. It was about schools.

I thought if every teacher in every school in America could inspire his pupils with all the power he had, if he could teach them as they had never been taught before to live, to work, to play, and to share, if he could put ambition into their brains and hearts, that would be a great way to make a generation of the greatest citizenry America had ever had. All of this had to begin with the little unit. Each teacher had to do his share. Each teacher was responsible for the destiny of America, because the pupils came under his influence. The teacher held the destiny of a great country in his hand as no member of any other profession could hold it. All other professions stemmed from the products of his profession . . . It was the gateway to inspire the nation's succeeding generations to greater and more beautiful living with each other; to happiness, to health, to brotherhood, to everything!

Tags

Jesse Stuart

Jesse Stuart (1907-84), Kentucky poet, novelist, essayist, and sheep rancher, was first of all a teacher — a profession he entered just shy of his seventeenth birthday. Many years later he published The Thread That Runs So True, a memoir dedicated "To the School Teachers of America." (1985)