The Veil of Hurt

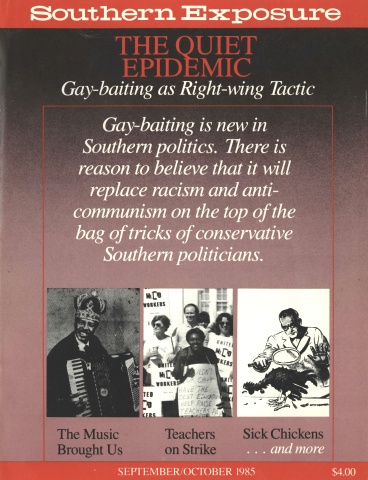

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 13 No. 5, "The Quiet Epidemic: Gay-baiting as Right-wing Tactic." Find more from that issue here.

I had completed all of the requirements for the Ph.D. at one of Virginia's state universities, including a first draft of a dissertation. The first two readers of the paper thought that the second chapter was particularly good, and was probably publishable as an article in one of the scholarly journals; needless to say, I changed that chapter hardly at all in the next draft. Between the time that the professors read the first and second draft, they came to believe that I was a homosexual.

My whole graduate program collapsed at that point. The chapter previously thought publishable was savaged. The paper was not good enough — could not be revised. Although the professors did not directly confront me with their prejudices, they conveyed their sentiments through indirect comments and incongruous criticisms of the paper itself. I was cold-shouldered, blacklisted, and all but thrown off campus. My adviser strongly resisted writing any kind of reference for me. Finally, he wrote something (insisting that it be confidential): obviously a "He was a student here, but I hardly knew him" kind of letter that could not possibly be of any value to me professionally. Having spent many years preparing for a professional career, but with no faculty support for my aspirations, I am now all but unemployable. I do not have any significant prior work experience.

I finally found a job as a clerk in a local department store. It did not take the spying and inquiring store detective long to reach the belated conclusion of the professors. He quickly spread his suspicions among other store employees. Young employees were told to avoid talking to me. I became the subject of vicious and unrelenting gossip. Insulting stage-whispered remarks were made for my benefit. Although the job wouldn't tax the intellect of a junior high student, I found that I couldn't cut it. Fearing for my sanity, I quit after two months.

I have now been unemployable

for many months. Leaving aside the issue of homosexuality, no one wants to hire an applicant with advanced graduate training for an unskilled position. I have now developed a love-hate feeling for Richmond and the Commonwealth. The many virtues of our area are all but cancelled out for me by the narrow-minded, self-righteous, mean-spirited, intolerance of all too many of our people.

— anonymous letter to the Richmond City Commission on Human Relations

Like the citizens of most American communities, particularly in the South, most proper Richmonders pretend that homosexuals could not possibly be native to their charming and innocent city, and that in the unlikely event that such people were to find themselves in our community, they would be treated like all visitors, with the most charitable of Southern civility.

According to a survey of the views of homosexuals in Richmond, Virginia, which we conducted in 1984, nothing could be further from the truth. In conjunction with the Richmond City Commission on Human Relations, we sampled opinions from 508 diverse individuals living or working in Richmond who identified themselves as gay, lesbian, or bisexual. Our questionnaire asked for a variety of information about their personal characteristics; their encounters with discrimination, harassment, and abuse; their confidence and trust in sundry community services and institutions; and the extent to which they publicly disclose their sexual orientation. Eighty-two percent of the respondents were white.*

The results of our study, like the words of our anonymous letter writer, suggest that many gays and lesbians see life in Richmond as anything but charitable and civil. One of the key items of the questionnaire asked each respondent to summarize his or her experience with mistreatment in various aspects of Richmond life. The answers indicate that discrimination occurs with astonishing frequency (see table 1).**

It is important that the highest number of complaints occurred in basic areas of life: public accommodations, employment-seeking services, routine health care, educational institutions, and opportunities for religious counseling. Finding and keeping housing proved to be the most substantial problem for many homosexuals. Thirty-two percent reported discrimination in getting and/or holding rental housing as individuals, followed by 23 percent who reported discrimination when they tried to rent housing with a roommate of the same sex. In almost every instance, white homosexuals reported more problems attributable to their sexual orientation than did black homosexuals. The small number of people reporting problems with lending institutions is due principally to the feet that few had sought loans from such institutions.

Discrimination in the workplace was the second major item of concern listed by our respondents (see table 2). Almost one-third — 31 percent — reported they were not treated as equal among heterosexual co-workers. Twenty-eight percent said they were harassed by co-workers and 25 percent reported being harassed by supervisors. There were seven specific forms of on-the-job discrimination, harassment, or intimidation in which 15 percent or more of the respondents reported incidents.

Perhaps the most alarming finding in our study was the extent of violence against gays, lesbians, and bisexuals (see table 3). A third of the sample — 156 people — said that they had been physically attacked or intimidated by heterosexuals in some fashion at least once because of their sexual orientation.

Because of the reported prevalence of discrimination and violence, the attitudes of the local government as a protector of civil rights are especially important in this study. Unfortunately, the respondents to the survey expressed extreme dissatisfaction with their treatment by public officials in Richmond (see table 4). Eighty-seven percent thought their concerns were never or rarely addressed adequately by city government. Similarly, 84 percent felt that they are treated unfairly under existing laws, and 78 percent said they receive less than equal treatment from local law enforcement officials.

The study also shows a disturbing degree of alienation and distrust for the law, local government, and the heterosexual community. It should come as no surprise that 16 percent of the sample said they were very alienated from Richmond's heterosexual community, and 70 percent felt at least some alienation. When asked to compare the quality of life in Richmond with that in other cities, just over half of our respondents rated Richmond in some degree unfavorably.

We consider one finding of our study especially disappointing. Among those institutions the respondents singled out as culpable are two in which anti-discrimination statutes are unlikely to have any measurable effect: religious institutions and the families of gays and lesbians. How can we expect fair and compassionate standards of treatment from government if justice is withheld by the very fountainheads of moral law?

The study gave no explanation for one surprising finding. Black people consistently reported lower percentages of mistreatment based on their homosexuality. We have three possible explanations. First, black gays and lesbians may attribute some discrimination to their race instead of their sexual orientation. The survey did not ask questions which could separate the two forms of discrimination clearly. Second, whites may be more aware of discriminatory acts based on their homosexuality because they have higher expectations of democratic pluralism in the community. Third, the white community as a whole may be less tolerant of homosexuality and therefore more prone to engage in or permit discrimination.

Faced with discrimination, the vast majority of the respondents to the survey reported that they find it necessary to modify their behavior to avoid unfavorable reaction from the larger community (see table 5). Even when dealing with financial institutions, three-fifths said they changed the way they behave to try to avoid discrimination. Four-fifths said they had to alter their behavior in their family or workplace.

Since 1983, three similar studies have been conducted elsewhere, and all lend credence to our findings. The first, conducted by the Alexandria, Virginia, Human Rights Commission and the Alexandria Community Gay Association, used a questionnaire adapted from the one used in Richmond. The results were astonishingly similar (see table 6). The other two comparable studies are one undertaken in 1984 by the National Gay Task Force, which combined data from 1,420 gays and 654 lesbians in seven cities; and "the Boston Project," a survey of 1,340 gays and lesbians in Boston. One parallel between the Richmond study and the surveys of other cities was the shocking rate of violence reported against gays and lesbians. In Richmond, 35 percent of males and 28 percent of females reported being attacked because of their homosexuality; in Boston, the figure was 25 percent overall; in the study of seven cities, 28 percent of males and 36 percent of females reported being the victims of violence.

Striking as the results of the Richmond survey are, it is likely that many of the numbers presented here underestimate the actual magnitude of the problem for at least two reasons. First, only 21 percent of our sample said that they reveal their sexual identity publicly, and the rest consequently may escape some malevolence at the hands of heterosexuals. For example, our survey showed that those who are openly gay at work have more than twice the risk of being attacked physically or verbally. Second, many victims of discrimination repress their memories of insulting or painful episodes.

The report to the Richmond City Commission on Human Rights concludes with recommendations of a number of steps that should be taken to bring unqualified citizenship to sexual minorities. The responsibilities entailed in meeting these recommendations fall to government, commerce and industry, the media, health care providers, educational institutions, labor unions, professional associations, religious institutions, family members, and gays and lesbians themselves.

First and foremost, we must have federal and state human rights laws which protect everyone, including homosexuals. Next, we need to repeal all present laws which single out homosexuals for disadvantageous differential treatment and those laws which seek to regulate private sexual behavior among consenting adults.

Essential too is that we offer realistic sex education to children, including the facts about homosexuality. Similarly, we must educate and train our police and other human-services workers so that they may carry out their responsibilities in a more equitable manner. Also essential is establishing local working committees of homosexual leaders with the police, housing industry, religious institutions, and so forth. And there is a crying need to create the means to control violence perpetrated against the homosexual community.

Finally, we must in more imaginative ways encourage the families of homosexuals to assume responsibility for finding out more of the facts about homosexuality, renouncing the myths and prejudices about gays and lesbians, and attempting to offer greater understanding and support to their homosexual family members.

Whatever the flaws of this particular inquiry, our fondest hope is that it and studies like it elsewhere will serve our communities by stimulating informed dialogue. Our further wish is that this dialogue may lead us closer to freedom for those who have been excluded, with no diminution of the liberties of others.

Notes

* The findings presented here are excerpted from the original 106-page report presented in April 1985 to the Richmond Commission on Human Relations.

** Percentages throughout this article are based on the numbers of people who gave answers to given questions. Inapplicable or missing data are excluded.

Table 1. Percent Reporting Discrimination in Selected Community Spheres

Total Race

White Black

% % %

Private Rental 32 34 25

Renting with Same-Sex Mate 23 24 13

Restaurant Services 23 24 18

Employment Services 21 23 19

Routine Health Care 18 18 17

Education/Schools 18 18 13

Hotel/Motel Accommodations 18 18 15

Buying a Home 15 19 1

Religious Counseling 17 19 4

Mental Health Services 14 15 12

Public Housing 11 5 11

Transportation

(taxi, plane, bus, train, etc.) 10 10 7

Emergency Health Services 6 5 6

Banks/Savings and Loan 6 6 5

Funeral/Burial Arrangements 5 5 4

Food Stamps 4 * *

Rape Counseling 3 * *

Welfare/Public Assistance 3 * *

Credit Card Companies 4 * *

Mortgage Companies/Private

Lending Institutions 3 * *

* Percent of those reporting discrimination is less than 5%

Table 2. Percent Reporting Selected Types of Discrimination in the Workplace

Total Race

White Black

% % %

Not treated as equal among

heterosexual co-workers 31 34 17

Harassed by co-workers 28 28 28

Harassed by supervisors or superiors 25 25 25

Didn’t get a job you were qualified for 24 25 23

Difficulty maintaining job security 22 17 23

Didn’t get a promotion you deserved 21 21 21

Fear for your physical safety 18 17 21

Fired or asked to resign 14 14 14

Lost customers or clients 14 14 12

Received poor work performance

evaluations 14 14 11

Received unfavorable job references 13 13 12

Difficulty getting a desired transfer 11 9 12

Barred from practicing your trade or

profession 7 6 9

Table 3. Percent Reporting Being Attacked or Abused

Total Sex Race

Male Female White Black

% % % % %

Ever Been Attacked 33 35 28 33 30

Table 4. Perception of Treatment by Local Government

Total Race

White Black

% % %

Gay/Lesbian Issues Never or Rarely

Adequately Addressed by City

Government 87 88 80

Receive Less Than Equal Protection

Under Current Law 84 87 73

Receive Less Than Equal Treatment

From City Police 78 78 76

Table 5. Percent Reporting They Alter Their Behavior In Order To Avoid Negative Reactions

Total

%

Family 79

Workplace 79

Religious Institutions 76

Public Accommodations 76

Educational Institutions 75

Recreation 73

Neighborhood 72

Retail Services 71

Legal Services, Courts 66

Government Services 65

Health Services 63

Housing 62

Financial Institutions 61

Table 6. Comparison of Reported Discrimination in Richmond and Alexandria

Richmond Alexandria

% %

Not Treated As Equal Among Heterosexual Co-workers 31 30

Harassed By Co-Workers 28 29

Harassed By Supervisors or Superiors 25 29

Discouraged From Renting with Same-Sex Roommate 23 19

Restaurant Services 23 20

Disclose Their Sexual Orientation to Everyone at Work 21 16

Hotel/Motel Accommodations 18 20

Routine Health Care 18 20

Tags

Edward Peeples

Edward Peeples, Jr., teaches preventive medicine at the Medical College of Virginia and is former chair of the Richmond Commission on Human Relations. (1985)

Walter Tunstall

Walter Tunstall teaches psychology at St. Leo College. (1985)

Everett Eberhardt

Everett Eberhardt, a civil-rights lawyer, is a research specialist for the Commission on Human Relations. (1985)