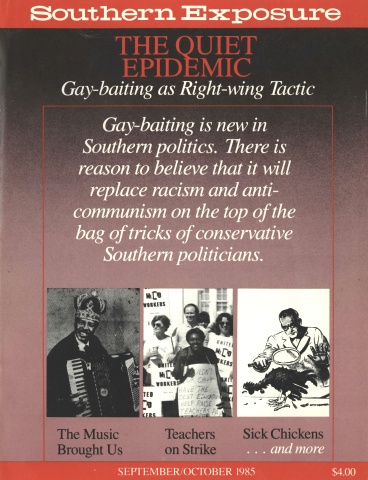

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 13 No. 5, "The Quiet Epidemic: Gay-baiting as Right-wing Tactic." Find more from that issue here.

In a dramatic demonstration of militancy, courage, and frustration, Mississippi school teachers went on strike early in 1985 for the first time in that state system's history. The February walkout spread to involve more than 9,000 strikers — over a third of all Mississippi teachers — and 466,000 schoolchildren.

Mississippi's history of entrenched segregation and alleged misuse of school fund tax appropriations — in the face of little allowed response by teachers — left many surprised by the depth and frustration of the strike.

"Yep. The strike was our final card, after years of political abuse, lies, broken promises, threats, low wages, no health insurance, little or poor equipment, and fear," said one striker. "Jones County started it and then we all voted with our feet. I saw a new breed of teacher in Mississippi. People who said they would never do such a thing as strike went out on the picket line."

A sore point in the ongoing struggle has been the allocation of funds from state appropriations to public education. State officials argue that several attempts have been made to raise revenues for teacher salaries over the years, but teachers argue that they never get the money.

A case in point is the hot debate which raged in 1966 on whether to legalize liquor in the state or to continue the hypocrisy of being a dry state. The legislature legalized liquor, the state became the official bootlegger, and the money from this "sin tax" was to go to teachers. The liquor profits went into a general fund. Reportedly, the teachers never saw a penny.

Similarly, when the sales tax was increased in 1968, income taxes were raised, and a state withholding system was started for the first time. Teachers were to get a $1,300 raise. Again, strikers argued, these monies ended up in the general fund and never got to teachers' paychecks.

Under Governor William Winter's administration, the Education Reform Act of 1982 declared that the "commitment of the people of Mississippi to this program has been underlined by the investment of a very substantial additional amount of their taxes. It is our responsibility to ensure that we get our money's worth." This sweeping attempt at reform involved implementing a statewide kindergarten program, a compulsory education law, revised high school graduation requirements, and new teacher certification requirements. It also suggested timidly that "the teachers, to the extent possible, should receive salaries that are at least equal to the average of the salaries received by teachers in the southeastern United States."

This meant that a new teacher entering the system with a bachelor's degree would make $11,475 a year. If a teacher pursued a doctorate and continued to teach for 17 years, she or he would be eligible for a top salary of $19,825. This salary could be supplemented by the local school district; this supplement ranges from $4,803 in Claiborne County to nothing in Tunica County. The average county supplement is about $600.

During the next gubernatorial administration, Governor Bill Allain found a loophole in the reform act's suggestion that the raise be "to the extent possible." Allain, who was put into office with the support of teachers, nevertheless claimed that Mississippi was too poor to raise teachers' salaries. Allain contended that continued tax increases would result in an erosion of public support for education and further economic decline in the state. As a result, salary increases were again denied, instigating a stand-off between the governor and the legislature on the one hand, and a majority of the teachers, some parent-supporters, and the Mississippi Association of Educators (MAE) on the other. The teachers and their supporters were especially angry that in the first legislative session of 1985 the lawmakers had voted themselves a $6,000 pay increase.

Since the beginning of integration, wealthy whites have established private schools or "academies" with student bodies increasing to 20 percent of the school-age population. Legislators are the ruling class, as it were, of the entire state. A majority of their kids are sent to private academies — blatantly racist, all-white, right-wing fundamentalist schools; 60 percent of private academies in the state are not even accredited. Yet these Mississippi "public servants" refuse to fund education for black and poor children.

Judy Barrett, veteran teacher, president of the Bay St. Louis Teachers Association, and first-time striker, calls the legislative action the "Mint Julep Law." In an interview at the Bay St. Louis Pizza Hut (one of many local businesses that supported the teachers' strike), Barrett and Peggy Dutton (communications person for the teachers' group) talked about the strike:

Judy Barrett: "It's more than just a raise in my paycheck. The whole future of public education is at stake. If something doesn't happen now, there will not be enough teachers to open school in August. If you were offered $11,000 here and $20,000 coming from a surrounding state, which would you take? Dedication does not put meat and potatoes on your table."

Peggy Dutton: "Yes, and I want my profession to be valued. Whether it's a dollar and cents value, an impact on the system, or the fact that I am producing the most important product Mississippi has. I want a dollar and cents value put on my profession. Say, look, you are worth something to me."

Judy Barrett: "We all need more money to get by. But more important, I see this as a move among Mississippi teachers for self-respect. For power."

Peggy Dutton: "We have been a powerless bunch all along. We have been described as docile. This is the first time teachers have moved to gain that kind of power and I think that it is a tremendous advantage to the children we teach. I don't think it's good that kids are being taught by people who feel powerless. The kids see us that way. I think the kids will gain when we go back into the classrooms as a group of people who stood up for what was right and made people do what they should have done a long time ago. We won the day we walked out of the classroom."

On March 12, in the middle of the strike, Alice Harden, a young black woman — a product of Jackson schools, a teacher, and president of the MAE — addressed her colleagues: "Ours is a struggle we cannot and must not lose, and in this struggle we have one advantage, one strength so great and powerful that it means we cannot lose our struggle. We have one another."

In her "Letter to Mississippi Teachers," Harden wrote, "The 20th Century finally caught up with the state of Mississippi and we, the Mississippi Association of Educators, brought it here. . . . The times of passive acquiescence are over. Those times are gone forever — and we will not allow them to come back. We stood up to the Governor and the Legislature, and we said, 'We will have justice. We will not participate in the demeaning of our profession or of the children and communities we serve.' They said, 'Accept things as they have always been.' We have answered them with strength, unity and determination to change the system forever."

Was the system changed fundamentally? No, even though legislators were forced by the strike and public pressure to vote a $77.6 million teacher pay and tax plan which amounted to an increase of $4,400 in teachers' salaries over a three-year period.

The impasse continued as Governor Allain vetoed the pay increase bill. At first the MAE called for upholding the governor's veto because the bill contained a harsh, outrageous, and presumably illegal anti-strike provision that would apply not only to teachers but any civil servant. But when MAE organizers finally pushed the strike forward, Hinds County (Jackson) chancellor Paul G. Alexander found the MAE and its officers in contempt and threatened them with fines and jail sentences for encouraging teacher walkouts.

On March 19, the MAE decided to call off the strike and back the legislature's attempt to override the governor's veto, contending that any pay increase was a victory. The anti-strike language of the law could and would be tested in court, they said.

What, then, did change during this struggle? The teachers themselves. Never again will they be passive or support a governor like Allain who turns his back on them. They have experienced a unity, and an understanding of how racism has hurt everybody, and they built a new degree of self-respect.

What changed was the mindset of the public and definitely of its teachers. No longer will they allow the ruling class legislators to go unchallenged. As Alice Harden reminded MAE members: "United and strong we will return home to fight the current battle and begin to win the long-term struggle in which we are engaged."

Tags

Trella Laughlin

Trella Laughlin is a native of Jackson, Mississippi, and graduated from Central High School its last year as an all-white school. She has been a college professor and is a journalist and activist. (1985)