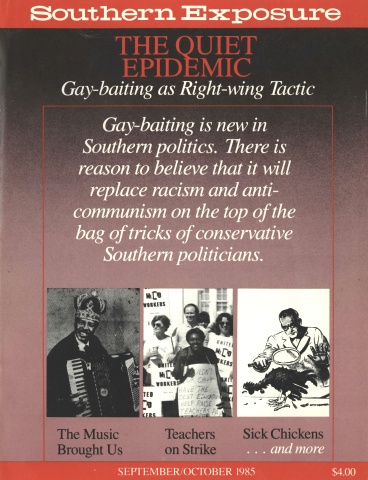

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 13 No. 5, "The Quiet Epidemic: Gay-baiting as Right-wing Tactic." Find more from that issue here.

"Power and authority are not the same. Those who hold the power to control people may not have the authority to do so. . . ."

The quotation was neatly taped to the cover of the scrapbook Wilhelmina Armour had just pushed across the table to me. The insurgent concept, couched in calm, reasonable terms, seemed to fit Armour perfectly. Here was a stern black woman who chose her words carefully and diplomatically, yet had become the center of a stormy education workers' strike in the heart of the South.

Armour is the president of the St. John Association of Educators (SJAE), an organization which pulled the sleepy Louisiana parish of St. John the Baptist into the twentieth century. In a region of America where unions are scarce and strikes as frequent as August snow, the St. John teachers' strike generated amazing public support and changed the political dynamics of the parish forever.

Petrol on the Bayou

St. John the Baptist Parish is a strip of land that hugs the Mississippi as the river winds its way through Louisiana spilling into the warm Gulf waters. Its rich delta soil and steamy summer heat made it productive sugar cane terrain for over a century. For years the lives of its inhabitants were shaped by the plantation economy, with most people finding themselves tied to the endless misery of cane production. Black laborers chopped cane in the subtropical heat until the long wooden handles of the cane knives were worn smooth.

During the 1950s several dramatic changes began to occur in the economic and political structure of the parish. Petrochemical corporations such as Du Pont began to construct gleaming plants along the river's banks, taking advantage of the proximity to oil and gas sources, cheap labor, and the river's transportation and dumping potentials. This process was hastened by a state government eager to overlook the pollution of the river in exchange for modem work for their constituents, as well as an occasional bribe. These factors, accompanied by the mechanization of agriculture, shifted the economic and, ultimately, the political life of the parish.

By 1980 the livelihood of St. John residents had been radically transformed. As early as 1960 over 30 percent of the parish's workers were engaged in farm and food production, mostly in the low-wage sugar industry. By 1980 this had dwindled to only 8 percent with less than 2 percent of the workforce directly employed in agriculture.

This shift in occupations was matched by the construction during the 1970s of an imposing elevated interstate highway through the vast swamp separating New Orleans from St. John. The highway contributed to the migration of many whites to the cities of Reserve and LaPlace on the east bank of the river.

These economic changes began to alter the racial and income contours of the parish. Twenty-five years ago St. John had a slight majority of blacks. By 1980 whites had grown to 62 percent of a total population of 32,000. The median income spiraled to more than $20,000 annually, a figure twice as high as that of many neighboring parishes. This prosperity was shared by a segment of the black population which found employment in the higher paying chemical industry, although one out of four black families in the parish still has an income below the federal poverty level.

River Lords and Vassals

For decades the government apparatus was dominated by the Montague family of St. John, which presided over its plantation and sugar refinery in customary Southern aristocratic fashion. At the head of the Montague oligarchy was J. Oswald Montague, superintendent of schools. Some St. John residents took to calling him "Cape Longue," translated from Creole as "Long Coat," an allusion to his alleged practice of filling his coat with silver coins to purchase favors. Over the years he had managed to turn the school system into a powerful patronage machine. Wilhelmina Armour recalls, "He ruled everything . . . and many people owed their jobs to the Montagues . . . they controlled the power in the parish." Political opponents of Montague would on occasion find that ballot boxes were being tossed into the river or votes openly purchased. Montague's influence stretched from the school board to the parish council; his empire embraced all spheres of St. John residents' lives, creating a tightly ordered political structure that resisted grassroots democratic change.

As the economy changed, the plantation and aristocratic form of rule began to erode. Fewer people owed their livelihood to the Montagues and subsequently the Montague influence began to diminish. Yet no single political faction emerged that could exercise the same sweeping power as the old order, and the superintendent's office continued to wield a powerful influence. During the last decade some school board members ran on mild reform platforms, but the board remained more of an appendage to the school superintendent than a governing body. Armour bristles at the suggestion that the appointive superintendent's office was subordinate to the school board. "For years it has been sort of a dictatorship, a political thing," says Armour. "As far back as I can remember the superintendents that I work under just stayed in office until they died." Board member Martin Bonura argues that the present superintendent simply ignores board decisions. "He has the control over the board," says Bonura.

In recent years the board has been split into two factions, referred to by insiders as the "big five" and the "little five." The big five generally served the interests of the present superintendent, Albert Becnel, who has held the position for 21 years. It was the defection of one of the "big five" members to the "little five" side that set the stage for an almost farcical power struggle within the board during the ensuing strike.

The Strike

The St. John teachers' strike began during the sweltering heat of late August 1984, and continued for eight tumultuous weeks. At the center of the battle was the St. John Association of Educators (SJAE), an affiliate of the Louisiana Education Association.

The initial dispute with the board was over a promised wage hike, but soon the right of the SJAE to collective bargaining became paramount. During the summer of 1984 the teachers had joined in a campaign for a tax increase to benefit education, with a commitment from the board that they would receive a 5 percent wage increase, the first in five years. Later that summer it became clear that the superintendent and the board were not going to issue a raise, and soon the strike was on.

Wilhelmina Armour's rise to the presidency of the SJAE was sudden. The previous president had resigned for personal reasons, and Armour was serving as secretary for the group when she volunteered to negotiate with the board prior to the strike. The membership was sufficiently impressed with her leadership that they elected her president immediately. Although the local and national press referred to the strike as a "teachers'" strike, in fact less than half of the employees who struck were actually teaching. More than 400 "support workers" — janitors, cafeteria workers, secretaries, and bus drivers — joined the SJAE overnight and went out on strike with the teachers. The support workers were represented on the "crisis committee," the principal executive body of the SJAE, and voted on all issues during daily meetings of the whole organization. While only one-third of the initial SJAE members were black, a majority of the support workers were black, giving the strike strong roots in the black community. Reflecting on the role of the support workers, Armour points out, "The support workers did help the strike in that, had the bus drivers not gone on strike, they would have brought those children to school. Had the secretaries, the cooks, and the janitors not gone on strike, I imagine they would have had some semblance of learning going on."

Community support for the strike astonished everyone in this conservative right-to-work state. The decidedly anti-union New Orleans Times-Picayune ran a front page poll that indicated the majority of St. John residents favored collective bargaining for the teachers. Support came from a myriad of parents' groups and labor unions in the parish, as well as teachers' organizations around the state.

The depth of the support was owed to several factors. First, the unwillingness of the school board to enter into meaningful negotiations created a tremendous amount of bad publicity. Because of the dispute within the board and between factions of the board and the superintendent, board meetings were chaotic and frequently deadlocked. On several occasions the teachers and parent groups attended board meetings, only to have the board go into executive session in order to meet privately. A local ministers' group, state legislators, and even Governor Edwin Edwards offered to negotiate the dispute, only to be rebuffed by the board.

While this kind of behavior has become a hallmark of Louisiana's chicken-coop politics, the new residents were aghast at the open incompetence and corruption of their governing bodies. Board member Bonura claims that the new white arrivals formed the mainstay of teacher support, along with the black population. It became clear that patronage was harming the quality of education. Armour observed that the board had "created a monster that this community has long been disgusted with, but nobody did anything about it." Adding to the board's image difficulties, it hired two notorious anti-union consultants who counseled board members to refuse to allow collective bargaining. The SJAE, on the other hand, came to be recognized as more concerned than the board with education and the welfare of the students. Their demands appeared to be a vehicle for changing an education system anchored in a hopelessly antiquated mode of government.

On October 17 the school board issued an ultimatum: return to work by Friday or face termination. "Of course this frightened a number of them [strikers] and they began to trickle in," says Armour. "What we were afraid of was that as they trickled in this would break the strike."

The board agreed to hold a referendum on collective bargaining for teachers in January, and although the legality of such a referendum was questionable under Louisiana law, the strikers took the offer. "As an alternative we agreed," says Armour, "but that was not the consensus of all the teachers, including myself. At no point did I try to influence the teachers, until the night before. I felt that many of them had gotten despondent, they were beginning to feel it financially, even though they had gotten loans. Many of these people were the sole support of their homes and they were beginning to feel it."

Unfortunately for the SJAE, the state supreme court later ruled that the referendum was illegal, and the issue of collective bargaining and unionization went back to the board. But during the strike the SJAE devised a strategy to respond to this contingency. They initiated a campaign to recall selected board members, including former SJAE president Martin Bonura.

A sufficient number of signatures was gathered to secure recall elections for six board members; however, a court ruling threw out three of the petitions. Armour believes that if new board members are elected the possibility of winning collective bargaining might increase. Apparently the current members consider their positions stable. Since the end of the strike they have embarked on a series of school closings and staff layoffs, which have met with sharp community opposition.

Aftermath

Whether or not the St. John teachers' strike was a success depends on the criteria used to evaluate it. There were small accomplishments often overlooked by the media's focus on personalities and issues rather than the organizing process. For instance, the strategy of involving all education workers — not just the teachers — in the action played an enormously important role. Aside from doubling the strikers' numbers, the strategy brought in several hundred black workers and their families, providing a solid base of support in the black community. By the end of the strike nearly one out of 20 workers in the parish was directly involved. This approach had repercussions even on a statewide level. For the first time in history the support workers were given full voting rights at the state convention of the Louisiana Association of Educators; and a St. John support worker was promptly elected vice-president of the state organization.

Given the strictly segregated nature of parish life in previous years, the importance of racial unity among education workers cannot be overestimated. For years two education associations existed side by side in the school system, for the most part racially segregated. The strike overcame those differences and undermined prejudices to the point that a predominantly white teachers' group elected a black woman (Armour) as its leader. This new-found unity is already being tested by the board through a series of personnel transfers which resulted in white teachers and administrators being replaced by blacks, exacerbating racial tensions.

In addition, Armour claims that a new generation of leaders emerged through the daily mass meetings of the SJAE where all decisions were debated and voted upon. This experience with direct democracy was the first for many who had endured decades of powerlessness.

There is evidence that the strike generated a more confrontational attitude in other segments of the community. Recently a group of St. John High School students staged a walkout, protesting the transfer of school administrators. Similarly, the recent St. Bernard Parish and Mississippi teachers' actions appear to be part of a wave of Southern organizing efforts sparked in part by the St. John experience.

Finally, Armour insists that the strike was not focused exclusively on collective bargaining. Initially the teachers asked only for their raise and the reinstatement of some threatened benefits. They were not interested in unionization. The teachers were seeking representation in the decision-making process, says Armour, and their experience with the board convinced them that they needed an agreement in the form of a binding contract. "I often equate this to the American Revolution," says Armour, "like the colonists that had the position of no taxation without representation. The teachers were doing the same thing . . . we had no say, no input at all."

Despite the failure to gain collective bargaining, all sides agree that the education workers are a new force in parish politics. Even Bonura, one of the teachers' recall targets, admits the strike served a progressive role. "In a sense the strike was a good thing," says Bonura. "It woke up people."

Understanding the outcome of the strike requires acknowledging that it became substantially more than what appeared on the surface. The transformation of the St. John strike from a modest wage request to a major political upheaval was the result of several factors. Initially, the extensive alteration of the economy eroded the power base of the old autocratic ruling structure, the plantation aristocracy. A vacuum occurred as the social class of small merchants competed with or battled against the continuing power of the education patronage machine. While the manipulators of this machine assumed it retained its ability to coerce and control the public's behavior as the Montagues had done, in fact it had lost a great deal of power and outgrown its function. It lacked the economic coercive powers the Montagues had wielded through controlling their plantation, refinery, and government hirelings. Just as the invading petrochemical industry had torn asunder the economy of die parish, the resultant development of new social groups and democratic expectations began to tear asunder the political life of the parish.

At this juncture, a crisis was waiting to happen. The precarious power of the school board was challenged by the growing number of residents impatient with the politicization of education, and by the education workers' increasing desire for control over the work process. In the ensuing factional dispute between board members and the superintendent, the strikers managed to surface as the most competent leading body. A new economic structure demanded a new decision-making process, and this demand was at the heart of the strike.

If the gauge for a successful strike is the ability to secure a favorable contract, then the St. John effort was a failure. But if success is gauged by the achievement of the organization in upsetting the old political order, securing changes in government policy, overcoming racial divisions, and uniting diverse groups of workers in preparation for future conflicts, then the strike was a sterling victory.

Tags

Lance Hill

Lance Hill is an activist/journalist living in New Orleans. (1985)