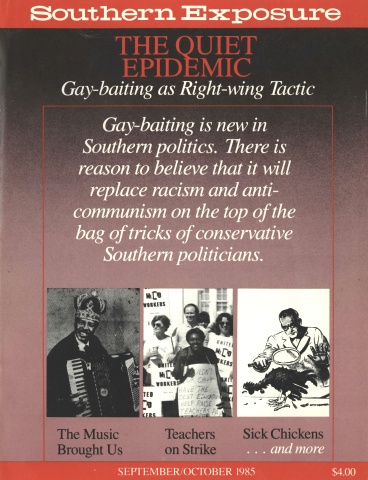

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 13 No. 5, "The Quiet Epidemic: Gay-baiting as Right-wing Tactic." Find more from that issue here.

French-speaking Louisiana is involved in an exciting cultural and linguistic renaissance as Cajuns and Creoles, once dangerously close to complete acculturation, begin to reclaim their heritage. The Western world as a whole has found it difficult to avoid the homogenizing influence of American culture, yet America has failed to reduce its own diverse ethnic and cultural heritages to pabulum, largely because of the resiliency of the individual cultures. This failure, however, must also be credited in part to the deliberate, concerted efforts of visionaries who foresaw that the trend toward a bland, standardized society would one day break down and prepared for a time when America would recognize the value of its highly seasoned cultural stew. As early as the 1930s, Louisiana French society was encouraged to maintain itself as an example of cultural and linguistic tenacity. The ideal vehicle for this effort, expressing both language and culture, was Cajun music.

Most of Louisiana's French population descend from the Acadians, the French colonists who began settling in eastern Canada at Port Royal, Acadia, in 1604. Very quickly, they came to see themselves as different from their European forebears, and for a century thrived in their new homeland. In 1713 England gained possession of the colony and renamed it Nova Scotia, and in 1755 the British Crown deported the Acadians. After 10 years of wandering, many Acadians began to arrive in the French colony of Louisiana, determined to recreate the cohesive society they had known in Acadia. Within a generation, these exiles had so firmly reestablished themselves as a people that they became the dominant culture in south Louisiana and absorbed the other ethnic groups around them, with a cross-cultural exchange that produced a new community, the Cajuns.

It is doubtful that the Acadian exiles and earliest French settlers brought musical instruments with them to colonial Louisiana. Melodies came with them, but instruments of any kind were rare on the early frontier. However, even with houses to be built, fields to be planted, and the monumental task of reestablishing a society, families would gather after a day's work to sing complaintes, the long, unaccompanied story songs of their French heritage. They adapted old songs and created new ones to reflect the Louisiana experience. They sang children's songs, drinking songs, and lullabies in the appropriate settings and developed play-party ditties for square and round dancing. These songs expressed the joys and sorrows of life on the frontier. They told of heady affairs and ancient wars, of wayward husbands and heartless wives; they filled the loneliest nights in the simplest cabins with wisdom and art.

By 1780 musical instruments began to appear. The violin was relatively simple and, played in open tuning with a double string bowing technique, achieved the conspicuous, self-accompanying drone which characterized much of traditional western French style. Soon fiddlers were playing for bals de maison, traditional dances held in private homes where furniture was cleared to make room for crowds of visiting relatives and neighbors. The most popular musicians were those who could be heard, so fiddlers bore down hard with their bows and singers sang in shrill, strident voices to pierce through the din of the dancers. Some fiddlers began playing together and developed a distinct twin fiddling style in which the first played the lead and the other accompanied with percussive bass second or a harmony below the line. From their Anglo-American neighbors they learned jigs, hoedowns, and Virginia reels to enrich their growing repertoire which already included polkas and contredanses, varsoviennes, and valses a deux temps. Transformation in fiddle and dance styles reflected social changes simmering in Louisiana's cultural gumbo.

In the mid- to late-1800s, the diatonic accordion, invented in Vienna in 1828, entered south Louisiana by way of Texas and its German settlers; it quickly transformed the music played by the Cajuns. This loud and durable instrument became immediately popular. Even with half of its 40 metal reeds broken, it made enough noise for dancing. When fiddlers and accordionists began playing together, the accordion dominated the music by virtue of its sheer volume, an important feature in the days before electrical amplification. Limited in its number of available notes and keys, it tended to restrict and simplify tunes. Musicians adapted old songs and created new ones to feature its sound. Black Creole musicians played an important role during the formative period at the turn of this century, contributing a highly syncopated accordion style and the blues to Cajun music.

Eventually, dance bands were built around the accordion and fiddle, with a triangle, washboard, or spoons added for percussion. Some groups added a Spanish box guitar for rhythm. They performed for house dances and later in public dance halls. By the late 1920s, musicians had developed much of the core repertoire now associated with Cajun music.

At this point, the unself-conscious pursuit of cultural and social rebuilding was jarred off its course by a series of events that brought Cajuns and Creoles into closer contact with the rest of the world: the discovery of oil in their homeland, World War I, the advent of mass media, and improved transportation. State and local school board policy began imposing compulsory English-language education and banned French from the elementary schools. In south Louisiana, French culture and language were slag to be discarded in the rush to join the American mainstream.

Class distinctions which had appeared early in Louisiana society were heightened by Americanization and the Great Depression. The upwardly mobile Cajuns offered little or no resistance to what seemed a move in the right direction. Money and education were hailed as the way up and out of the mire. Being "French" became a stigma placed upon the less socially and economically ambitious Cajuns who had maintained their language and culture in self-sufficient isolation. The very word "Cajun" and its harsh new counterpart "coonass" became ethnic slurs synonymous with poverty and ignorance and amounted to an accusation of cultural senility.

The Cajun music scene in the mid-1930s reflected the social changes. Musicians abandoned the traditional style in favor of new sounds heavily influenced by hillbilly music and Western swing. The once dominant accordion disappeared abruptly, a victim of the newly Americanized French population's growing distaste for the old ways. Freed from the limitations imposed by the accordion, string bands readily absorbed various outside influences. Then the advent of electrical amplification made it unnecessary for fiddlers to bear down with the bow in order to be heard, and they developed a lighter, lilting touch, moving away from the soulful intensity of earlier styles.

By the late 1940s, commercially recorded Cajun music was unmistakably sliding toward Americanization. Then in 1948 Iry Lejeune recorded "La Valse du Pont d'Amour." He went against the grain to perform in the old, traditional style long forced underground. Some said the young singer from rural Acadia Parish didn't know better, but crowds rushed to hear his highly emotional music. His unexpected popular success focused attention on cultural values that Cajuns and Creoles had begun to fear losing.

Iry Lejeune became a pivotal figure in the revitalization of Cajun music; his untimely death in 1955 only added to his legendary stature. Following his lead, musicians like Joe Falcon, Lawrence Walker, Austin Pitre, and Nathan Abshire dusted off long-abandoned accordions to perform and record traditional-style Cajun music. Local music store owners pioneered a local recording industry that took up the slack left by the national record companies which had abandoned regional and ethnic music in favor of a broader, national base of appeal.

The effects of revitalization were immediate but varied. Cajun music was stubbornly making a comeback, but not without changes brought on by outside influences superimposed during the previous decade. To remain a legitimate expression of Louisiana French society, Cajun music would need to revitalize its roots. Yet tradition is not a product but a process. The rugged individualism which characterized frontier life has been translated into modem terms, yet its underlying spirit persists. The momentum of recent developments will carry traditional Cajun music to the next generation. Meanwhile, a steady stream of new songs shows the culture to be alive again with creative energy. Fiddler Dewey Balfa is prominent among the current generation of musicians who want the culture and music to breathe and grow — but also to stay clearly within the parameters of tradition. Balfa and his brothers have been an influential force in the Cajun music renaissance.

The Balfa Brotherhood

Every school day, a few dozen children from the countryside around Basile, Louisiana, pile into a schoolbus driven by one of the most respected folk musicians in America. Since the early 1960s, Dewey Balfa has been an important figure in the movement to preserve the traditional ethnic and regional cultures. He and his brothers formed the core of the Balfa Brothers Band which brought Cajun music to folk festivals all across America. Their sense of tradition was based on a rich musical heritage which ran in the family. Balfa says, "My father, grandfather, great-grandfather, they all played the fiddle, and you see, through my music, I feel they are still alive."

Balfa's father, Charles, was a sharecropper on Bayou Grand Louis in rural Evangeline Parish near Mamou. He inspired his children with his great love of life and of music. Will, Burkeman, Dewey, Harry, and Rodney grew up making music for their own entertainment in the days before television. Unlike some other traditional musicians, who learned to play in spite of their parents, the Balfa brothers did not have to sneak to the barn to play the accordion or unravel window screen wire for makeshift cigar-box fiddles. The Balfa household swelled with music after the day's work, and children were encouraged to participate with anything they wanted to try to play. Spoons, triangles, and fiddlesticks were important first steps to teach rhythm. Fiddles, however, took time to master.

When I was little, as far back as I can remember, I always loved music. Of course, we didn't always have instruments around, but I would take sticks and rub them together pretending to play the fiddle and I'd sing. So my late father said to my mother, "I want to buy a fiddle for Will because he's always pretending to play with those sticks. " We had an old neighbor who had a fiddle that he didn't play much. So one day my father traded him a pig for the fiddle. And that was the first fiddle I had. Later, when I had learned well enough to play dances, I ordered another one from the Spiegel catalog. I paid nine dollars for that one.

— Will Bolfa [his preferred spelling]

The Balfa Brothers Band came much later.

Dewey was younger than me. When he started playing, in fact, he learned on my fiddle. Then, when I got married, I took my fiddle with me, so he bought himself one and continued to play. One day in 1945 or 1946, he came to my house with a fellow named Hicks. He was the one who owned the Wagon Wheel Club, and he lived next to my father, who came with them. They came with a flask of whiskey, and I had given up drinking and music in those days. They had me take a drink with them. I didn't know what they were after. We talked a little. Later, he said, "Get your fiddle." I said, "My fiddle? But I'm out of practice." Hicks said, "Get your fiddle. I want to hear you and Dewey play together. " And that was the beginning of the Balfa Brothers Band. If it hadn't been for that, I would have left my fiddle in the closet.

I found my fiddle and took another drink to warm up. We played two or three songs and Hicks said, "You 're going to come play for me next Saturday night. " I said, "Oh, no, I can't go. " I just had my old Model A, and the club was on the other side of Ville Platte from here. He said, "Yes, you all come, you and Dewey." That was before he made his big club. So we started going, Dewey and I and one of our friends who played guitar with us. We were three. Two fiddles and a guitar. We would go every Saturday night to play until midnight for five dollars apiece. Sometimes, when it was time to stop, they would pass the hat and pick up more than we had already made, so we played on until near dawn. We played for some time like that. We had no amplifiers. We just played acoustic. Dewey was working offshore, and he said, "We're going to get together a real band." He went out and bought a set of amplifiers. Then we were really set up.

— Will Bolfa

In 1964, Dewey Balfa served as a last-minute replacement on guitar to accompany Gladius Thibodeaux on accordion and Louis "Vinesse" Lejeune to the Newport Folk Festival. An editorial in the local newspaper commented condescendingly on the notion of festival talent scouts finding talent among Cajun musicians, and predicted embarrassing consequences if indeed Louisiana was so represented in Newport.

I had no idea what a festival was. They were talking about workshops, about concerts, and I didn't have the slightest idea what those were. I've always loved to play music as a pastime. I've always looked on music as a universal language. You can communicate with one, you can communicate with a whole audience at one time. But then, here I was going to Newport, Rhode Island, for a festival. I had played in house dances, family gatherings, maybe a dance hall where you might have seen as many as 200 people at once. In fact, I doubt that I had ever seen 200 people at once. And in Newport, there were 17,000. Seventeen thousand people who wouldn't let us get offstage.

— Dewey Balfa In 1967, Dewey told Newport fieldworker Ralph Rinzler that he felt it important to present his own family's musical tradition. That was when the Balfa Brothers Band was first invited to perform at the Newport Folk Festival. The brothers, who had not played together for some years, were a little rusty, but they quickly got a great deal of practice at festivals all over America, Canada, and eventually France. The group — composed of Dewey and Will on fiddles, Rodney on guitar, Rodney's son Tony on drums or bass, occasionally Harry or Burkeman on triangle, and accompanied by various friends like Nathan Abshire, Marc Savoy, Hadley Fontenot, Robert Jardell, or Ally Young on accordion — became known in folk circles far and wide as proud representatives of their native culture. More important, they brought this renewed pride back home to Louisiana, to their people who had carried the stigma of sociolinguistic inferiority for years.

When we first started going to the festivals, I can remember people saying, "They're going out there to get laughed at." But when the echo came back, I think it brought a message to the people, that there were great efforts being made by people who were interested in preserving the culture on the outside. But a lot of people don't realize that they have a good cornbread on the table until somebody tells them.

— Dewey Balfa

Dewey's timing could not have been better. The creation of the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL) in 1968 testified to a changed cultural climate. CODOFIL chair James Domengeaux focused initially on political maneuvers and language education but soon became convinced of the importance of the culture in preserving the language. The first Tribute to Cajun Music festival, presented March 26, 1974, and sponsored by CODOFIL in cooperation with the Smithsonian Institution, was deliberately planned to capture the local audience in an unconventional setting to call attention to the music that they had come to take for granted in smoke-filled dance halls. As a participant, Dewey had other motives.

It was a festival for the people. It was a lesson for the cultural authorities. At the time, I wanted for those people who hold the reins of the culture to be exposed to the Cajun music experience so that they could see what the people felt about their own music when presented in such a prestigious setting. I wasn't worried about the audience, because I had been in front of audiences before. I knew what the reaction would be out there. You can feel the response of the people when you 're playing. But the people who have the power of decision-making, I could never get them to see what music means to the people. I could never get in front of them to play, so we got them to stand backstage, and I think that festival did it.

— Dewey Balfa

The festival has made cultural heroes of its performers and, in the same motion, placed them within easy reach of the people, offering alternative role models for young musicians. The importance of this alternative to music imported from the outside was the basis for Dewey's message.

I can remember doing workshops away from home. People were so amazed by the music, and when I'd tell them about the culture, they just couldn't believe it. And the question would always come up: do you think that this music, language, and culture will survive? And I had my doubts because there was nobody who would work in the fields and come back and sit on the porch or sit by the fireplace and play their instruments and tell stories from grandmother and grandfather. Instead, kids would come back from school and do their homework as fast as they could and then watch television. A lot of artificial things, instead of the real, down-to-earth values. And I thought that the only way it would survive, could survive, was to bring this music into the schools for the children. I never thought it would happen, but I kept pounding and pounding at the door until finally I got a grant [a Folk Artist in the Schools grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, sponsored by the Southern Folk Revival project in Atlanta]. I feel that the program has done a lot of good. It has alerted a lot of children that this is not just so-called 'chanky-chank' music. It's a music of the people, played by the people for the people.

— Dewey Balfa

In spite of their tremendous influence on the national scene during the 1970's, the Balfas lived quite ordinary lives back home in Louisiana. Their popularity had little effect on their everyday lives. Will operated a bulldozer for Evangeline Parish, Rodney and Tony laid bricks, and Dewey still drives a schoolbus and has a discount furniture store.

I've been playing music for over 40 years and I've been married for 38 years, and I'm still with the same woman, still play the same music. I've always loved music, but I always played my music and came home. There are some musicians who like to drink and run around, and I like to drink a bit, but then I like to come home. I've always been like that. I would go out and make my music, make my money, and go home. I love my wife, my children, my grandchildren. Those are what I live for.

— Will Bolfa

In 1978, Dewey's brothers Will and Rodney were killed in an automobile accident in Avoyelles Parish near Bunkie while on a family visit. In 1980, his wife, Hilda, who had always provided him with a secure home base from which to work, died of trichinosis. Though these personal tragedies in Dewey's life affected him very deeply, after a period of mourning for each he resumed his work, marked by a certain feeling of urgency about preserving the ground they had gained together. In recognition for his musicianship, as well as his eloquent spokesmanship in behalf of the traditional arts and cultural equity over the years, Dewey was awarded the National Heritage Award in 1982 by the National Endowment for the Arts. He carries the spirit of the Balfa Brothers with Rodney's son Tony and a family of friends who help lighten the load.

Mr. Rinzler asked me at a festival one time, "Do you realize how many lives, how many people the Balfa Brothers have affected through the years of music?" I said no. And I really had no idea. We were promoting the group. We were promoting the culture. We never thought that we were bringing the music to different people and different places. We always thought that the music was bringing us.

— Dewey Balfa

Tags

Barry Jean Ancelet

Barry Jean Ancelet is a folklorist at the University of Southwestern Louisiana in Lafayette. (1991)