Mixed Marriage

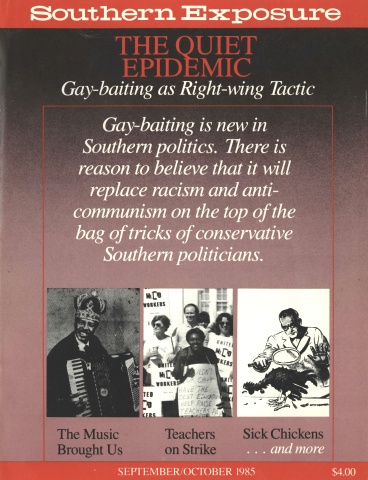

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 13 No. 5, "The Quiet Epidemic: Gay-baiting as Right-wing Tactic." Find more from that issue here.

Her greatest pleasure, bless her heart, is watching me eat. Just last week she dropped by the house with some homemade pickles. I opened a jar, sat down in the kitchen, and proceeded to make her happy. My mother-in-law makes great pickles.

"Yum, yum," I said.

She looked at me adoringly and began puttering about the kitchen, closing cabinet doors I had left open. For some reason open cabinet doors make both her and my wife nervous. It's not the only thing they have in common.

I love my mother-in-law. It's un-American I know but I just can't help it. She is such a charming Southern lady and so is my wife, Dixie. They are very much alike. Two black-eyed peas in a pod who have managed to convert me, a yankee, to the Southern way of life.

If only they wouldn't talk.

The English have a saying, a bit of homespun advice given traditionally to young men contemplating marriage: "Take a bloody good look at her mother, lad." Good advice, but I would add: "And take a bloody good listen to her, too."

My mother-in-law is a slow talker. A Southern slow talker and that is the worst kind. If the 1988 Olympics have a slow talking competition, you will see her on TV. She will be the lady with the gold medal around her neck singing the national anthem. They will have to slow the music way, way down for her. Otherwise, by the time the music ends she will be somewhere around "the dawn's early light" pronouncing every syllable clearly, distinctly, and s-l-o-w-l-y.

"Good pickles, Mom," I said.

"Thank you, honey," she drawled. She was examining some of the plants and flowers Dixie had everywhere in the kitchen. It's another thing they have in common — plants. They buy them, trade them, transplant them, talk about them, and, as they say in the South, "Smell of them."

"You know," she began, pausing for a breath, "I — was — just — wondering — about — these — flowers."

"Whaddabout 'em?" I asked.

"Well," she cocked her head and made a sucking sound through her teeth, "they — just — don't — look — like — they — are — doing — very — well."

I bit my tongue, trying desperately not to interrupt.

"So — I — was — thinking," she continued, "that — maybe — they — would — do — better. . ." "Ifwegavethemsomewater," I blurted out rudely.

"No," she said. "They — seem — to — be — moist — enough. (Pause) What — I — was — thinking — about — was — that — maybe — they — would — do — a — little — better. . ."

It was agony. I could feel the muscles tensing up across my shoulders, my toes curling inside my shoes.

". . . if — they — were — closer — to — the — window. . ."

I leaped to my feet and began moving the plants to the big window sill.

"That — way — they — would. . ."

"Getmorelight," I said, making my third trip.

". . . take — advantage — of. . ."

"Morelight," I said, putting down the last plant."

". . . the — morning — sunshine."

My pulse was pounding, my forehead beaded with perspiration. These confrontations take a lot out of me. As the years go by she is either talking more slowly or I am becoming less patient. Maybe both.

Unlike her mother, my wife is not a slow talker, but she does have that negative Southern way of asking questions. "Are you not tired?" she will ask. I never know what to say. A simple "yes" or "no" seems to leave the question still in doubt. To prevent confusion I usually answer with a declarative sentence. "I feel rested and well," I respond a bit self-consciously.

We had some friends over for dinner a while back. They used to be friends. Now, I'm not so sure. While Dixie was clearing the dessert dishes she asked, "Who would like coffee?"

Several of our guests said they would. But not me. I had had my quota for the day. As Dixie picked up my dish she asked, "Do you not want coffee?"

"Yes," I answered.

A few moments later Dixie put down a cup of coffee at my place. "I don't care for any, Dixie," I said.

"You said you did."

"No I didn't," I insisted.

"I'm sure you did," she stated.

"She's right," one of our female guests said. "I heard you."

"You heard wrong, my dear," I said, forcing a smile. "Dixie asked, 'Do you not want coffee,' to which I answered 'yes.'"

"So why did you change your mind?" she asked.

"I did not change my mind," I said a little too loudly. The conversation across the table stopped suddenly. I forced another grin. "If Dixie would have asked, 'Do you want coffee?' I would have said 'No.' However, what Dixie did in fact ask was, 'Do you not want coffee' to which I answered 'Yes.'" To my surprise I found myself on my feet, gesticulating wildly.

"Calm down," Dixie whispered.

"I am calm," I sputtered. "Just trying to make a point."

Our guests were deliberately not paying attention to us. I suppose they thought they were witnessing a major marital crisis.

If it had ended there, everything would have been all right. Dixie and I had survived numerous tumbles down "Communications Gap" in the past. We always landed on our feet laughing about it. Not this time. I sat back down and began a conversation with the guest on my left when I noticed Dixie was still standing behind me.

"Do you not want coffee, or what?" she asked.

Something snapped inside me. "No, I do not want coffee," I bellowed. "Or maybe I should say, 'Yes, it is coffee I do not want.' No coffee for me. Yes, on the no coffee question." I was on my feet again pointing to the coffee cup she held in a trembling hand. "I have a negative desire for that."

The evening went downhill after that. People began yawning and looking at their watches. "Would you look at the time." "Where has the evening gone?" "I'll bet the babysitter is wondering about us."

After our guests left, Dixie and I cleaned up in a strained silence. I hummed a few bars of "Yes, We Have No Bananas" but she paid no attention to me.

We went to bed and lay quietly, back to back, for several minutes before I ventured a hand over to her side beneath the sheets. She responded with a squeeze. Good woman. "Would you not like to fool around?" I asked.

She laughed, turned on her side and nuzzled my neck. "Are you not too tired?" she asked.

Tags

Chap Reaver

Chap Reaver, Jr., is a 50-year-old chiropractor who lives in Marietta, Georgia. When he sent us this story he wrote that he and Dixie have been married for 25 years and are perfectly compatible except for the language barrier. He said, "I don't think I can last much longer unless we get this worked out. Please buy and publish this story. You will be saving a good marriage." (1985)