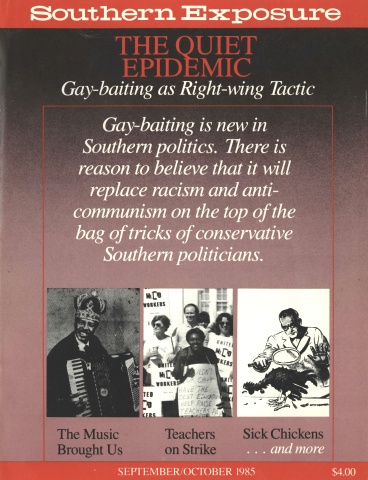

Gay-baiting in Southern Politics

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 13 No. 5, "The Quiet Epidemic: Gay-baiting as Right-wing Tactic." Find more from that issue here.

Gay-baiting is new in Southern politics. There is reason to believe that gay-baiting will replace black-baiting as the meanest article in the bag of tricks for conservative Southern politicians. Certainly the white Southern electorate, considerably less provincial and less prejudiced against blacks than before the Civil Rights Movement, and the increasing participation of blacks in regional politics, means that any black-baiting today, especially in a statewide campaign, must be far subtler than before. This is hardly the case with gay-baiting.

Mississippi 1983

In Mississippi the gubernatorial campaign in the fall of 1983 had been quiet. Attorney General Bill Allain, the Democratic candidate, was way ahead in all the polls. No one predicted a Republican victory in this state whose last GOP governor was chased out of office in 1875 at the end of Reconstruction.

Less than two weeks before the election, all hell broke loose when three black drag queens in the state capital of Jackson produced sworn statements, supported by results from lie detector tests, charging Allain had frequently paid them for sexual relations over several years. Allain immediately denied the charges as "damnably vicious, malicious lies." Outgoing Governor William Winter said he "couldn't recall a race of such vicious attempted character assassination and personal attack."

Nightly appearances on statewide television by the drag queens in question made their accusation the principal issue, or at least incident, of the campaign. Sworn statements by Jackson police officers saying they had seen Allain cruising in areas frequented by black male prostitutes provided additional evidence that the attorney general had crossed racial as well as gender lines in his sex life. Allain, divorced since 1970, had never remarried, while Leon Bramlett, the Republican candidate, had been campaigning all along as "a family man."

The voters of Mississippi were confused over what and whom to believe. Allain had been a popular attorney general, noted especially for his advocacy for consumers. The charges against him were powerful stuff — "real gutter politics . . . can't get much gutterier," according to one longtime observer of Mississippi politics. But the role of Concerned Citizens for Responsible Government, a group organized by top Bramlett supporters, in locating the drag queens and then paying their expenses during several days of overwhelming media attention to this incident not only raised serious doubts about the truth of the charges but also stirred up some backlash against Bramlett. Hinds County (Jackson) supervisor Bennie Thompson, a black Democrat, said at the time that most voters saw the incident as "a desperate roll of the dice on behalf of the Republicans." Concerned Citizens for Responsible Government replied that they were trying to spare Mississippi the embarrassment it had suffered only a few years earlier over the career of Congressman Jon Hinson. Elected to Congress in 1980 after denying allegations of homosexuality, Hinson, a Republican, was later forced to resign after his arrest for attempted sodomy in a House office building men's room in Washington.

On election day, Mississippi voters elected Bill Allain their next governor. He won easily, but not by the 20-point margin predicted before the emergence of the three black drag queens. But what to make of the effect of gaybaiting on this election in Mississippi? The consensus, according to Kirk Phillips, chair of the Democratic Caucus of the Mississippi Gay Alliance, is that the charges of sex with black men lost Allain some votes, but not many: "A lot of people couldn't fathom it at all. A lot of people didn't believe the accusations or didn't want to believe them, and a lot of members of the local gay community think the charges were probably true."

Texas 1984

Gay-baiting erupted into attention in Mississippi in 1983. In Texas in 1984 it mainly simmered. The office in question was a United States Senate seat open by retirement of the incumbent; and the object of the gay-baiting, from the spring primary campaign through the November general election, was Lloyd Doggett, a liberal Democrat.

It started during the last two weeks before the May primary. Kent Hance, the most conservative of the Democratic candidates, who has since switched to the Republicans, pointed out on a number of occasions that Doggett had the endorsements of the gay political caucuses of Houston, Austin, and Dallas, and also that of Lesbian and Gay Democrats of Texas. (These four gay groups had indeed endorsed Doggett.) In the general election campaign, from early summer on, Republican candidate Phil Gramm, a congressman who had himself first run as a conservative Democrat before switching parties, picked up Hance's themes that Doggett was soft on homosexuality, labor unions, and military matters.

It was an incident from back in May that turned up the heat on gay-baiting in Texas. The Alamo Human Rights Committee, a gay organization in San Antonio, gave Doggett a $604 contribution, $354 of which had been raised at a male strip show. Doggett later returned the contribution when he learned how it had been raised and when it began to surface as a campaign issue.

Months later, in August, the Gramm organization ran a saturation radio advertisement campaign using a tape in which a woman announces she is going to talk about "gay rights, male strip shows, traditional family values, and the Texas Senate race. And gay rights. Lloyd Doggett actively sought and received the endorsement of gay and lesbian groups and supports the gay rights bill which would give homosexuals special status before the law. It would also make them eligible for a hiring program previously reserved only for minorities. Homosexual groups in San Antonio even had the poor taste to hold an all-male strip show to raise money for Doggett." Following up on the radio campaign, Gramm accused Doggett of "undermining family values" and "pandering to homosexuals."

In what one observer described as "an unusually negative campaign, even for Texas, where cactus and barbed wire are as common in politics as on the plains," gay-baiting was only one of several points of the attack Gramm made on Doggett. But it seemed to be the charge that threw Doggett most off balance. The Democrat's usual response was that he was not for special status for gays, but didn't plan to engage in a campaign of hate against them and supported the idea of protecting them against job discrimination. "Given the choice between a candidate who opposes job discrimination for gays and one who supports cuts in Social Security, I think I know where Texans will be anytime," Doggett argued.

Lloyd Doggett was mistaken. Phil Gramm, along with Ronald Reagan and a horde of fellow Republicans, won in Texas. Many observers say the effect of the gay-baiting on the outcome of the election was, as in Mississippi, hardly decisive. According to Janna Zumbrun, founding co-chair of Lesbian and Gay Democrats of Texas, gay-baiting "was a factor and hurt Doggett, but, considering the Gramm landslide, it was only one of several factors accounting for his loss."

In the wake of November's conservative victory in Texas came a decided defeat for gay politics in Houston. In January 1985, conservatives forced a referendum on a city ordinance prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in municipal employment practices. (Chapel Hill, North Carolina, whose 1975 personnel ordinance prohibits job discrimination on the basis of "affectional preference," is the only Southern jurisdiction with such gay rights legislation in place.) After a strong campaign by Republicans and business interests and a low turnout by progressive and even gay voters, the anti-discrimination ordinance was repealed by a vote of 82 percent to 18 percent. Lee Harrington, past president of the Houston Gay Political Caucus, reports that the Houston referendum fight lacked the "real intentional meanness" of the Gramm campaign against Doggett. Harrington believes that the defeat in Houston, a city with a reputation more progressive than it deserves, stemmed from the prevalence of more misinformation than could be combatted and reveals the extensiveness of the gay educational, as well as political, agenda.

The referendum raises questions about the future of progressive as well as gay politics in Houston. Annise Parker, current chair of the Gay Political Caucus, reports increasing death and bomb threats left on the telephone answering machines of gay and lesbian activists. She also reports some distancing occurring between local straight politicians and the gay community. But she believes that, despite the referendum results, the gay community still has lots of friends and the progressive electorate is still strong. Former Gay Political Caucus chair Larry Bagneris anticipates a tight battle between Mayor Kathy Whitmire, a leading advocate of gay rights, and her conservative opposition in the city elections in November 1985. Annise Parker agrees that the campaign will be rough, but notes that Houston voters are fairly sophisticated: "Whitmire has been gay-baited in the past, both times when she has run. And both times she has won."

Tags

Joe Herzenberg

Joe Herzenberg is a gay political activist and former town council member in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. (1985)