Facing South: Rebels in Law

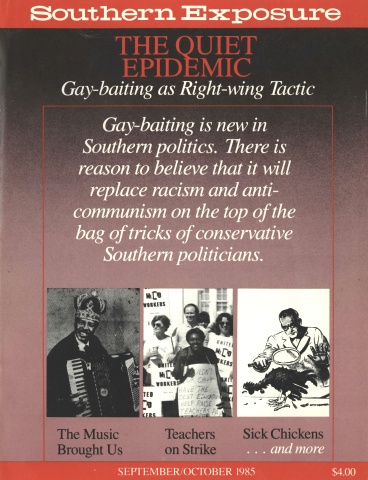

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 13 No. 5, "The Quiet Epidemic: Gay-baiting as Right-wing Tactic." Find more from that issue here.

Two years ago, Laurie Fowler and Vicki Bremen, then recent graduates of the University of Georgia Law School, knocked on doors of Atlanta law firms. What they wanted was shingle space for a practice in the emerging field of environmental law. "You don't want to be with us,'' they were told. "We're on the other side. We represent the defendants."

Fowler and Bremen were determined to use their legal skills on behalf of the environment, not industry. They saw a need for legal assistance to those confronting Georgia's environmental problems — a result of the state's rapid growth. In-state population increased 20 percent between 1972 and 1982, while the city of Atlanta witnessed some $3.7 billion worth of new construction projects in the first half of 1984 alone. With Georgia already ranked 20th nationally in generating hazardous waste, Bremen and Fowler decided it was time to do something: they opened a Georgia branch of the Legal Environmental Assistance Foundation, or LEAF.

Originating in Birmingham, Alabama in 1979, LEAF is the South's only regional public interest environmental law firm. It was founded in response to the Sunbelt's burgeoning environmental problems — water pollution, waste disposal, and energy use, all part and parcel of the region's rapid expansion. The LEAF chapters — located in Tallahassee, Florida; Knoxville, Tennessee; Birmingham, Alabama; and Atlanta — share a common board of directors, regional grant money, and some projects. But each office raises most of its own funds, has its own members, and chooses its own cases, focusing primarily on local problems.

Thirteen-year Georgia resident Vicki Bremen was a registered nurse when, at age 40, she decided, "I wanted to refocus my career" on health-related environmental issues. The Sierra Club veteran saw law school as the best way to get involved. There she met 25-year-old Laurie Fowler. Finding a close match between their philosophies and aims, they decided to team up to tackle environmental law.

Fowler and Bremen see Georgia LEAF as a watchdog, ensuring compliance with federal, state, and local codes. But, says Fowler, it's not easy to get public and private sectors to work together unless they are "prodded with a stick." That's what we sometimes have to do, she adds.

Little more than a year after its founding, Georgia LEAF has one staff attorney (Bremen), an office manager, more than 200 paying members, and a lot of volunteer help. The chapter's organizational members include such groups as the Atlanta Sierra Club, which pays a set fee for legal consultation and representation. And the two attorneys have been very, very busy:

• Georgia LEAF helped North Georgia residents win a temporary restraining order against the federal Drug Enforcement Administration's program of spraying the controversial pesticide paraquat on marijuana crops. The DEA must now produce an environmental impact statement.

• In response to complaints about the spraying of two potent herbicides, tordon and velpar, by the U.S. Forest Service on northern Georgia, LEAF produced a citizens' manual on pesticide regulation in order to provide Georgia residents with information on their legal options.

• Representing a citizens' group in White County, Georgia, LEAF won a court verdict preventing Oglethorpe Power Company from stringing high voltage lines across a scenic and historic stretch of the Sautee Valley. • Georgia LEAF furthered the campaign to deny an operating license to Georgia Power Company — the state's largest utility — for its Vogtle nuclear power plant on the Savannah River by raising unresolved health and safety problems and excessive rate hikes before the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

• LEAF recently drafted strengthening language for a weak Right to Know bill already introduced in the Georgia legislature.

In addition, Bremen drafted a report on the 50 municipal waste sites in Georgia that appear on the U.S. Superfund inventory. "The purpose," she says, "is to highlight the problems for the state legislature." The group has also been involved in controversies surrounding soil erosion and sedimentation, utility construction financing, and acid rain.

Has all this activity had any effect? "Georgia Power must now think before acting," Bremen and Fowler assert, "and the state environmental protection division knows we won't go away." Robert Kerr, director of the Georgia Conservancy, calls LEAF "a catalyst" and an "excellent" concept, but feels it's too soon to foresee LEAF'S impact. "They are taking on some controversial issues, ' ' Kerr says, "and there's a place for that in Georgia."

"One thing about the Southeast," says Bremen, "there's still time to make a difference.

LEAF can be contacted at: 1102 Healey Building, 57 Forsyth Street, Atlanta, GA 30303; (404)688-3299.

Tags

Lincoln Bates

Lincoln Bates has contributed environmental pieces to Oceans, Westways, Coastal Journal and others. (1985)