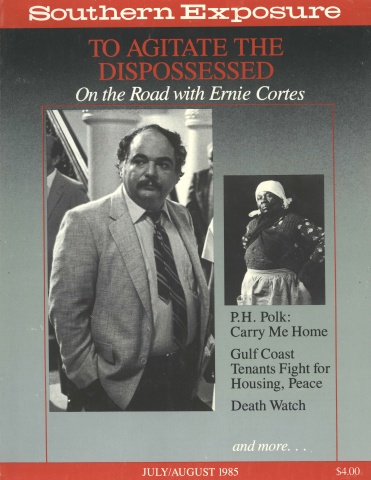

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 13 No. 4, "To Agitate the Dispossessed: On the Road with Ernie Cortes." Find more from that issue here.

On a cold November night late last year, Beverly Epps made history. As her fellow tenants looked on, Epps became the nation's first black woman resident of a public housing project to be named executive director of a local housing authority. "It feels very good to be part of history, but will it buy my Christmas presents?" Epps responded, in typical low-key fashion, to the appointment. During the same meeting of Louisiana's Jefferson Parish Housing Authority, tenants of Marrero's Acre Road housing project also celebrated the selection of Patricia Landry, another Acre Road resident, as its manager.

The two appointments, made by an all-male, mostly white, politically appointed housing authority, capped a string of victories won by the Marrero Tenants Organization (MTO) in 1984. Forceful protest, dramatic organizing, and attention-grabbing tactics are helping Marrero tenants roll back a decade of corrosive neglect of their housing project and win sweeping gains in their battle to secure decent housing. Throughout much of the organizing effort in 1984 a nucleus of tenants active in MTO, mostly black women, maintained as a priority their insistence that women who live in the project be afforded positions of leadership in managing their own living conditions.

Their unrelenting pressure on the white-controlled and male-dominated parish and HUD political establishments cracked the veneer at least enough for racist and sexist barriers to slip. Today, the four white and three black housing authority members interrupt each other at their monthly meetings to heap praise on the work being done by Epps and Landry to upgrade conditions in the Marrero project.

The parish authority is appointed by the seven-member elected parish council, and blacks account for less than 20 percent of the registered voters in the parish, which experienced substantial growth in the 1960s and 1970s as young whites fled to the suburbs mainly hoping to avoid school desegregation in New Orleans. About 1,000 residents live in the 200 units of the Marrero project, less than 30 minutes from downtown New Orleans.

One month before the historic November meeting these same tenants, joined by a New Orleans area cross-section of social-justice activists, grabbed the media's attention by marching across the Greater New Orleans Mississippi River Bridge — the first political march ever made across the bridge (see SE, Nov./Dec., 1984). That walk climaxed a three-day protest march by Acre Road tenants from their project on the west bank of the Mississippi River to the front door of the regional office of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) on Canal Street in downtown New Orleans.

The three-day march for "Housing and Peace," the most spectacular MTO project of the year, was made possible by months of intense, skillful organizing and protest against a multitude of inefficiencies and alleged illegalities in the management of public housing in Jefferson Parish. From the early part of 1984 on, the Marrero tenants were in the news almost daily — vocalizing demands, formulating charges of mismanagement, uncovering examples of horrendous neglect, and winning victories on the streets, in the courts, or with parish authorities and HUD officials.

After almost a decade of crying in the wilderness, Marrero tenant leaders are as suspicious of HUD as of the local housing authority. "I don't trust those HUD folks any more than I trust the white political establishment that makes up our local authority," MTO leader Rose Mary Smith tells her group time and again.

Until early 1984, the Jefferson Parish Housing Authority's monthly meetings were usually conducted in the law offices of former authority attorney Nathan Greenberg of Gretna. Council members routinely made appointments to the authority more to fulfill patronage obligations than because of candidates' qualifications or because of their dedication to bettering the plight of the less fortunate in the community.

For years Rose Mary Smith and her small band of tenant activists usually didn't know about the authority meetings until they were over. And if they attended, the authority went into executive session.

As far back as 1976, HUD, responding to tenant complaints, chided the authority for not having an organized maintenance program. In August 1984, when a damaging tenant-prompted management analysis was released by HUD, the authority was still being scolded for lack of an organized maintenance program.

Last year, tenants began chanting their litany of past and accumulated needs: lack of maintenance, leaky roofs, doors that wouldn't close, broken window panes they couldn't get replaced, insect infestation despite the fact the authority for years had illegally collected a pest control fee, worn out appliances, court-ordered evictions obtained by the housing authority to pressure tenants for back rent, poor exterior lighting, lack of concern on the part of authorities for unsightly junked automobiles, trashy streets and overgrown vacant lots, erratic and often changing rent calculations, a nonexistent waiting list for vacancies, the inability to find key authority workers such as the executive director and project manager and maintenance staff, and, still unresolved, the contention of tenants that utility charges are excessive and illegal.

With the exception of a still lingering battle over the utility charges and adoption of an acceptable utility allowance schedule, nearly all of the complaints outlined by tenants in early 1984 have been resolved or are on the way to being resolved.

Rose Mary Smith, Patricia Landry, and Beverly Epps see HUD's years of silence and the authority's legacy of inefficiency as part of a greater, more deeply rooted problem of a male-dominated, sexist approach to governing. "As long as many of the tenants of Acre Road were poor black women with children, and single parents, there wasn't much reason for the male-dominated HUD regional office, the male-dominated council, and the male-dominated housing authority to pay any attention," Smith says. "They figured we might come out on occasion to an authority meeting and try to reason and they would smile and be nice to us and we would go home and they could get on with their little club."

By 1984 Smith and the others had had enough. Eager for change, they were quick learners when Pat Bryant of the Gulf Coast Tenant Leadership Development Project came along to share his organizational and protest skills. "It didn't take much to turn that spark we had into a big old fire," Smith says. "We were ready to take to the streets and march and protest and make a presence at the authority meetings. And I'm proud of the fact it was still the women in the project with the children; only now, in 1984, we had some skills and we were fed up with being nice and being smiled at. We were not smiling back and it didn't take HUD and the parish very long to figure that out and when they figured that out a whole lot of things suddenly started to change."

In August 1984 — before the march — HUD released the lengthy management review of the Acre Road Housing Project. The damning document cited 38 major deficiencies in parish housing management, some that had remained uncorrected for 10 years. The review also recommended that, "Unless positive changes are made within the next six months, action should be taken to replace executive staff and the board of commissioners [the housing authority] as necessary."

The impetus for that management review came out of a stormy two-and-a-half hour faceoff in April 1984 between tenants and some top assistants of HUD regional director Richard Franco at the authority's offices in Marrero. But almost four months of unrelenting pressure by tenants — aided by veteran tenant organizer Pat Bryant — had been necessary to coax Franco's people out of the New Orleans office and into the project.

Once there, Franco's lieutenants were bombarded by an angry litany of past and present ills in the area of public housing management in Jefferson Parish. "We have been remiss in not being attentive to your problems in the past," John Warrick, a general engineer for the HUD regional office, told the tenants during that milestone April showdown. "I personally feel HUD has been negligent, but this is a new day and the ball is now in our court and it is our responsibility to help you," he said.

When the management review was finally released it revealed, among other things, that HUD had allowed the parish authority to be more than four years late in submitting a revised utility schedule as required by federal regulations.

This battle, by one relatively small group of tenants in one housing project in the Deep South, takes on national significance given what is happening to the country's public housing. The Marrero tenants say the very existence of public housing is endangered. Funds for housing have suffered greater cuts than those of any other program under the Reagan budgets. According to tenants, Reagan came into office planning to abolish public housing entirely, either by selling it to private landlords or demolishing it to make room for commercial investments. Protests by tenants nationwide forced the administration to back off these plans, and now Reagan has proposed selling public housing to the tenants themselves.

The Marrero tenants say what is happening in their community provides the real answer to housing problems — keep the government in the business of financing housing, but let the tenants run it.

"We can manage our housing better, more economically, more efficiently than the bureaucrats who have been messing up things for so long," Smith says.

In contrast to their attitude in years past, the local media have become perhaps obsessively fascinated with the small Marrero project, the tenant leaders, the housing authority, and the larger symbolic implications of what the media see as a classic struggle between poor, powerless, largely disenfranchised tenants and the white-dominated, insensitive parish political structure. Since March 1984, 56 stories about Marrero tenant struggles have appeared in The Times- Picayune/The States-Item, published in New Orleans and the state's major daily newspaper. The vast majority of those stories have been lengthy and prominently displayed, spread across the top of major metro news pages, carrying six-column headlines. That constitutes a lot of ink in a major daily newspaper for a housing project of about 1,000 tenants in a parish with a minority black population and where no blacks hold locally elected office (with the exception of one black state court judge sitting in Gretna, the parish seat).

Central to public and media awareness of the tenants and authority has been Pat Bryant, a former staff member of the Institute for Southern Studies. Bryant now directs the Southeast Project on Human Needs and Peace, an endeavor sponsored by the Southern Organizing Committee for Economic and Social Justice (SOC), War Resisters League Southeast, and the SOC Education Fund, to help develop grassroots movements for social change that join local and global issues. Beginning in early 1983, Bryant, Rose Mary Smith, and others in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama formed the Gulf Coast Tenant Leadership and Development Project, which provides support, technical and legal assistance, information, and leadership training for tenant councils along the Gulf coast. A veteran organizer, Bryant is articulate, intense, and capable of finding and nurturing would-be tenant leaders and helping them develop the self-confidence to press demands for reform.

Bryant rankles many officials from HUD on down. He also gets arrested from time to time — twice in recent months: once as part of a South Africa demonstration in New Orleans and more recently at a housing protest march in St. Charles Parish, upriver from New Orleans. He is supremely confident of his positions, more knowledgeable of HUD rules and state laws governing public housing than most officials, and possesses a country-preacher oratory zeal when needed.

Smith, Landry, and others had been laboring with the MTO for more than 10 years when they joined forces with Bryant and two other long-time New Orleans organizers who helped form the Gulf Coast Project — Jim Hayes, now president of the National Tenant Organization (NTO), and Ron Chisom. After getting the Gulf Coast Project launched, at the coaxing of Smith and Landry Bryant directed his organizing energies at the Marrero Project. "I quickly grasped that conditions there were deplorable; that neglect was rampant and that tenants there had been crying in the wilderness for a decade with no one listening," Bryant said. "They needed long-overdue help and they needed it fast and I felt if we could score some successes there, those successes could galvanize tenants in other projects along the Gulf Coast to start organizing and start asserting their rights, especially in New Orleans with its 90,000 long-neglected tenants."

By the end of 1983, the MTO began mapping its strategy to score quick victories, using a full arsenal of weapons including petitions, marches, pickets, and boycotts. The pressure the MTO was able to exert was enhanced by Bryant's ability to convince the media that the situation was worth their attention. And so, like a slumbering giant rudely awakened from a long hibernation, the Marrero housing authority suddenly found itself in early 1984 under serious siege.

In March 1984, tenants stormed a meeting of the housing authority and top HUD officials at the federal agency's Canal Street offices to demonstrate their anger at being consistently excluded from housing authority decision-making sessions. Tenants wanted to press demands in front of HUD and local authority members for new management, correct billing for rent and utilities, and badly needed repairs. As federal guards showed up to oust the demonstrators, HUD called off the meeting. Two days later tenants stormed a second meeting and left shortly before the arrival of federal guards, again summoned by HUD.

Those two meetings quickly resulted in tenant lawsuits in Orleans and Jefferson parishes, alleging violations of the state's open meetings law. The suits were filed by tenant organization lawyers Yvonne Hughes and Clare Jupiter. Jefferson Parish judge Floyd Newlin and New Orleans judge Revius Ortigue, Jr., came down on the side of the tenants in April and May, ordering the housing authority and HUD to open all their sessions to the tenants and the public.

Judge Newlin ruled that tenants clearly have the right to picket, threaten a rent strike, and press for reform in housing management. He also told the authority it could not avoid the open meeting law simply by taking the Jefferson body to Orleans Parish to meet with HUD. In addition, he threw out a countersuit by the authority's former lawyer, Nathan Greenberg, who had sought an injunction to stop tenants from picketing the housing authority offices in Marrero and publicly threatening a rent strike.

Also in March, after several picketing sessions at the authority's office, white executive director Joseph Werner bowed to insistent tenant demands and resigned. "Beautiful," said Rose Mary Smith. "We are very happy." Tenants maintained that they could hardly ever find Werner and that when they did he was insensitive to their needs. In a parting salvo, Werner said, "If the tenants would take care of the appliances and contents of their homes, without abusing them, we would not have the problems which they complain about today." According to the HUD management review, most of the 38 major deficiencies in management occurred while Werner was at the helm.

In April, over the intense objections of tenants, the housing authority named Joseph Jones as the new executive director. Jones, who is black, had been project manager for years under Werner; tenants said that he, too, was rarely available because of his fulltime job as a parish deputy. Rose Mary Smith tried to unseat Jones immediately, alleging that his choice had been made illegally by the board while meeting in executive session in Greenberg's law office, a meeting from which tenants were barred.

A week later, then-authority chair Pascal Scanio confirmed to this reporter that Jones was hired during a closed meeting, a violation of the state's open meetings law. But the authority went back into a special meeting a week later and rehired Jones. By July, Jones was in hot water with HUD for failing to furnish data needed to unravel the tenant allegations of utility overcharges. John Warrick, HUD's resident engineer, said that what Jones had provided amounted only to "mumbo jumbo." Parish district attorney John M. Mamoulides, angered by Scanio's admission of a blatant violation of the open meetings law in the initial selection of Jones, subpoenaed authority records. After reviewing the records he declined to prosecute, but in a sharply worded letter told the housing authority to get its house in order.

Also in April, HUD acknowledged the seething unrest in Marrero and Franco sent his top lieutenants into the project. That landmark session led to the comprehensive management review released later in the year.

By the end of August, tenants were given an audience with Franco and his top chiefs at the HUD offices. This session was a far cry from the previous occasions when Franco had called out the federal guards to oust them. It was at this meeting that Franco said, on the record, he would go to bat for them in Washington if they proved their case for utility rebates.

August also marked the release of the damning management review, which reads as a chilling litany to the years of accumulated abuse. One section of the report shows that for years the authority had illegally charged tenants one dollar a month for pest control, a service which HUD rules require to be provided free of charge. Rose Mary Smith says that she and others had known for years that the pest control fee was illegal and time and again their complaints fell on deaf ears. The authority is now awaiting HUD approval of a $48,000 item in its new budget to rebate tenants for the overcharges.

Meanwhile, tenants in Marrero and elsewhere on the Gulf Coast were turning their attention to national housing policies and priorities. They launched a petition drive calling on Congress to authorize the building of 10 million new housing units over the next 10 years. The petition said that this could be done for $60 billion a year and asked that the funds be obtained by cutting this amount from the military budget. They also asked that $40 billion be spent over two years to upgrade existing housing, with the jobs this would create going to unemployed people in the housing projects. In September, fresh from his election in Miami as head of the National Tenant Organization (of which MTO is a charter member), Jim Hayes addressed tenants on the Gretna courthouse steps, telling them he had appealed to HUD secretary Samuel Pierce for help in correcting utility overcharge problems in Marrero. He also announced that NTO had voted to conduct a national petition drive asking for funds for housing instead of bombs.

During September and October, tenants kept up the pressure for the removal of Jones through pickets and demands at housing authority meetings. On October 15, the authority fired not only Jones but also its attorney, Nathan Greenberg, and its accounting firm, replacing it with one of the area's few all-black accounting firms. Earlier in the year, during the court fights over the closed meetings, Greenberg had confided to this reporter that for almost a decade he had been successful in maintaining tight control over the housing authority, maintaining for it such a low profile that few in the parish even knew it existed. But he ruefully acknowledged then that Bryant had ignited a long-smouldering spark of dissent among tenants, had captured the media's attention, and that as a result he himself was losing control. Several months after his departure, Greenberg informed the new authority lawyer that he personally owned old authority records and legal documents and that the authority would have to pay him a fee if its staff wanted to see these papers.

By October, with Jones and Greenberg gone, tenants began a serious push to get Beverly Epps named executive director. HUD regional director Franco sent a letter to parish officials defining a position of interim director that was clearly tailored for only one man in the parish: Community Development director Emanuel Brown. In an angry showdown, tenants charged that an interim director was not needed, and that Epps, who had served as project manager during the short and stormy tenure of Jones, was more than capable and more than ready to take on the duties of executive director.

Franco would not back down. Shortly after that meeting, Jefferson Parish President Joseph Yenni "loaned" Emanuel Brown to the housing authority (at the request, he said, of both HUD and the authority), mainly to tackle the awesome task of responding point by point to the management review within 30 days. Tenants vowed to stage a dramatic protest. That vow quickly was translated into plans for the historic three-day, 15-mile "March for Peace and Housing."

With their lawyers poised to rush into federal court in an instant to raise constitutional questions, Smith, Patricia Landry, MTO vice president Verna Brown, Bryant, and other organizers took a positive public stance that the march would take place. The executive director of the Mississippi River Bridge Authority, Thomas Short, went on record as saying that if tenants got parade permits from the Jefferson Parish sheriff's office as well as the Gretna and New Orleans police departments, he would give them permission to walk across the bridge beginning at 10:30 a.m. on Monday, August 29, 1984.

Several local councilmen later told reporters privately that Short made the commitment in print after Bryant and Smith met with him and bombarded him with constitutional issues which they were prepared to raise in federal court if he tried to stop them. But, the councilmembers said, Short also made the commitment fully expecting tenants to fail in obtaining the other specified permits. "He walked right into a trap and didn't know it. He just wasn't sure on those constitutional issues if he had a solid position, but after he went public first, everybody else got scared and fell over themselves to grant permits," noted one councilman who refused to be identified.

The major disappointment in the march was the small turnout of only 110 marchers. Bryant had hoped that at least 1,000 people would join in, including tenants from Texas, Kentucky, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Florida. That did not materialize, but a group did come from Chattanooga, Tennessee, a city where blacks are pushing for public housing reform.

Bryant says part of the problem was that in the final days before the march, too much of his energy was diverted to the negotiations and away from organizing participants. "I think that was part of their strategy," he commented. "I think stumbling over each other and granting all the permits so easily, they felt the next best weapon they had was to hold down the number so they could say, 'Look, all this fuss over 100 or so people.' So I think they decided to keep us tied up in meetings over the route right up to the eve of the march, knowing we wouldn't have time left to get out the troops."

The march was precedent setting, both because previously powerless people had forced authorities to let them cross an attention-getting major bridge that had not been used by social-justice marchers before, and because the action joined tenants' local demands with national issues. Responding to a television reporter's question about how the issues of housing and peace were related, Rose Mary Smith responded, "What we are saying is that poor tenants in public housing cannot have repairs made to our homes or have enough public housing built as long as our government throws away billions of dollars on war."

The march attracted enormous publicity. The Times-Picayune/The States ltem, besides assigning this reporter to cover the whole march on foot, printed maps showing the route for each day's segment. On October 29, 110 tenants, singing "Ain't Gonna Let Nobody Turn Us Around," walked off the bridge about 12:15 p.m. onto Camp Street in New Orleans. Except for a charity jogging race the two previous years, this was the first time the span had been partially closed for pedestrian use and the first time ever for political protest. At the foot of the bridge about 50 New Orleans project tenants were waiting with banners held high, and they joined the protesters for the final leg of the march and the hourlong rally.

Not quite a month later, on November 28, the Marrero tenants rejoiced as Beverly Epps was named executive director, replacing Brown who had been on loan as interim director. At 42, widowed and the mother of five children, she has lived in the Acre Road Project since 1966.

Reaction from the regional HUD office was swift and punitive: on December 3, five days after the appointment, HUD chief Franco notified parish officials and the housing authority that he was withholding federal rent subsidies to the housing project to protest the naming of Epps. In a December 3 letter to Jefferson Parish president Joseph Yenni, Franco said: ". . . the recent decisions of your appointed housing authority board of commissioners to hire three inexperienced persons or firms to administer the public housing program does not appear realistic nor in the best interest of all the parties concerned . . . we are dismayed that the board has chosen to take the same type of irresponsible action which was the basis of our comprehensive review, therefore we are at this time withholding payment of operating subsidy to the low rent housing program."

It couldn't have been much clearer. Franco was saying he wasn't going to let HUD money flow into a housing project being managed by two black women and with its accounts being administered by a black CPA firm.

In the end, Epps and Landry stayed; the black CPA firm has a contract and now the authority is thinking of suing the white CPA firm it hired because they are refusing to turn over records showing how HUD modernization money was spent in 1982 when Joe Werner, a white, was executive director, Greenberg was lawyer, and the authority was all white.

"After the dismal record of the past two executive directors which has created serious problems for this authority and HUD, how can anyone suggest that I am not capable of handling all the duties?" Epps commented.

Authority member Victor Gabriel, a white Marrero investment counselor, was working on a compromise that would keep Epps on as executive director. But at an authority meeting on December 12, amid charges of racism and sexism from the tenants, Gabriel's plan foundered, failing to get support from other housing authority members and further eroding his own standing with tenants.

There were several reasons for the tenants' anger. Gabriel wanted to cut Epps's salary from $21,156 — the amount paid the two previous male directors, one of whom resigned under fire and one of whom was fired — to $16,800. He proposed also to restrict her management responsibility to only the Marrero project of 200 housing units and not all the units in the parish. Gabriel suggested further that the authority hire a chief administrative officer — at a salary of $18,156 — who would have authority over Epps and who also would be in charge of managing the approximately 1,500 units of privately owned, federally subsidized housing in the parish.

On December 13, Franco announced he was restoring the subsidy because he had received assurances that the authority would vote to demote Epps and hire a chief administrative officer. But on December 16, this reporter quoted high-ranking HUD legal staffers in Washington as saying that Franco did not have authority to cut or threaten to cut subsidies and was exceeding his authority in interfering in the local authority's choice of an executive director.

In numerous directives and statements, HUD has long encouraged local government officials to name tenants to positions on housing authorities and also to name tenants as project managers. HUD Washington attorney Joe Gelletich also said Franco did not have authority to withhold the rent subsidy because the local authority was late in submitting answers to the 38 management deficiencies listed in the review. At the same time authority member Eugene Fitchue, a black, said he would fight Gabriel on the HUD-backed compromise intended to demote Epps.

Meanwhile, the tenants were, reaching out to seek support from a broad range of groups in the New Orleans area. The day after Gelletich's opinions became public, there was a march in front of the HUD offices in New Orleans to demand that Franco be fired and replaced by Crystal Jones, a young New Orleans black woman active in tenant protests and a specialist in urban studies. Joining the tenants on the march were labor organizers, members of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) and the local Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador (CISPES), organizers for the NAACP and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), members of the Socialist Workers Party, and others. In Washington, lawyers specializing in housing issues contacted by Bryant huddled with top ranking HUD officials, threatening them with federal lawsuits.

Against that emotional backdrop, the local authority met on the night of December 19 in the parish council chambers in Gretna to try to resolve the Epps issue. Some 30 uniformed and plainclothes police officers ringed the meeting room. Chief Deputy Wallace Moll said they came because Gabriel had warned there might be demonstrations. Two parish councilmembers, Lloyd Giardina and James Lawson — who both said later that they were afraid the ill-timed Gabriel compromise would touch off a protest firestorm in the parish — intervened with Franco. With a subdued Gabriel conceding defeat, the housing authority in swift action rejected the compromise, restored Epps to her full authority at full salary, and agreed to advertise for a comptroller who would serve under her at slightly less pay.

At the helm for more than six months, Epps has reduced delinquent tenant rents by more than 30 percent, a fact that brings smiles to authority members who know those figures look good at HUD offices. New street lights have been installed at the project with the help of revenue-sharing money obtained by councilmember Lawson. New maintenance director Robert Drake, a young black man who works closely with Epps and Landry, found many gas dryers had dangerous connections that could explode, took them out, and got emergency HUD money to replace them. Epps made arrangements with Sheriff Harry Lee, the nation's first popularly elected Chinese-American sheriff, to borrow inmates under guard to come to the project to cut grass and pick up trash. She also persuaded parish officials to tow away junk cars that tenants had complained of for years.

Most importantly, earlier this year, for the first time in four years, HUD approved modernization money for the project. "That is nothing short of a strong vote of confidence for the job that Beverly Epps is doing as executive director,'' George Kelmell, the white chair of the local authority, said at a recent meeting.

The transition of local project power from the insensitive leaders of the past, who didn't live in and seldom visited the project, to tenant activists in leadership roles was symbolized at a recent workshop. Epps, Drake, and Landry hosted a one-day seminar at Acre Road on proper installation and maintenance of heaters and dryers. The workshop was attended by housing authority directors and maintenance directors from five parishes and HUD's regional office.

Midway through 1985, the long-overdue revised utility schedule still has not been adopted. Time and again, HUD has rejected proposed schedules submitted by the local authority in response to the management review. HUD has rejected the schedules mainly because tenants want electric dryers and air conditioners included in the utility schedule portion for which HUD provides payment subsidy. Tenants take a pragmatic position: dryers are essential to clean, well-kept families; air conditioners are essential in an area largely developed over swamps, below sea level, and in one of the most humid regions in the country.

HUD maintains that such appliances are not allowable, as they are not standard features of apartments. Marrero tenant leaders refuse to back off on that issue and the local authority — challenged at almost every turn for much of 1984, publicly embarrassed over the management review, and under fire from HUD, parish officials, and tenants — continues to submit for HUD approval utility schedules including the questioned appliances.

Another major unresolved issue which the Marrero tenants refuse to abandon is their claim that at least since 1980 — in the absence of a revised utility schedule as ordered by HUD — they have been systematically overcharged by about $2 million for utilities by the local housing authority. In late 1984, however, HUD released its own utility analysis of the Acre Road Project for the same period and asserted that tenants collectively owe the housing authority $100,000 and that the authority owes the tenants less than $100. Tenants, as expected, loudly rejected those findings and indications are that eventually the issue will wind up in federal court.

While the issue of utility charges lingers unresolved, tenants are still pushing for what they consider another vital unfinished item on their 1984 agenda: the appointment by the parish council of a tenant to the local housing authority. Rose Mary Smith, with the backing of MTO, has openly campaigned for her appointment, and Franco is on record in correspondence with Jefferson Parish President Joseph Yenni urging the appointment of a tenant to the seven-member authority.

Smith and her followers vow to keep up the fight to get her placed on the housing authority and prove their case for utility rebates. Despite Gabriel's appointment to the housing authority board, tenants hope their cause may be aided by the recent addition of a comptroller to the executive staff of the housing authority. He is William Offricht of Metairie, Louisiana, a retired regional HUD official who spent much of his public career in the assisted management housing branch of the federal housing program. Working closely with Epps and Landry, Offricht and the tenants hope that after establishing a routine he will be able to find time to tackle the long and tedious job of analyzing past records to answer, once and for all, the lingering utility overcharge issue.

In the meantime, Smith and other MTO leaders are sharing the stories of their victories with other tenant groups throughout the South and are urging peace groups, church activists, and others to join them in their demands that national resources be used to build housing and meet human needs instead of preparing for war. Tenants from all three states served by the Gulf Coast Project provided leadership at two regional workshops sponsored by SOC that brought together diverse groupings of peace and justice activists, both black and white. In the spring of this year, Rose Mary Smith was a featured speaker at the April Actions for Jobs, Peace, and Justice in Washington. She urged those assembled to oppose further cuts in federal funds for housing and to support the tenants' demands for 10 million new housing units. "There is no shortage of resources," she said. "All that has to be done is take it from the Pentagon."

Meanwhile, Bryant, Smith, and other MTO leaders have turned their immediate attention to aiding the protests of other tenants, in three small projects in St. Charles Parish, about 30 miles away from New Orleans. A recent protest march against the dilapidated conditions of the houses resulted in the arrests of 34 people, including children, on charges of obstructing traffic on River Road in Hahnville. Some of the protesters spent the night in jail. Those arrests prompted Kristin Gilger, bureau chief of the River Parishes Bureau of The Times-Picayune/ The States-Item, to criticize local police sharply in her weekly column. She remarked that public housing problems in St. Charles Parish go beyond rats and roaches in apartments, holes in ceilings, water faucets that don't work, and the unfair ways in which rents are calculated and utilities assessed. "The real issue is dignity. The tenants want a say in the way the housing projects are run and they want to feel that their views are respected and valued," Gilger said.

St. Charles Parish tenants were frightened and angered by the controversial mass arrests, but they have bounced back and claimed a major victory when parish housing authority director Jaynard Peychaud resigned on May 28. Peychaud gave no reason for his sudden resignation, but he has been under fire from HUD — as well as tenants — for unfair rent calculations, neglect of basic maintenance of the units, excessive utility charges, and a general lack of sensitivity on the part of him and his staff.

Patricia Batiste, president of the St. Charles Parish Tenants' Organization, says, "This is a victory. We have been misused long enough." She says tenants are also demanding the firing of housing authority employee Nancy Carter and will urge that a tenant be named to replace Peychaud.

Surprised by the sudden resignation, St. Charles Parish tenants rejoiced and then pressed on with plans for a protest march on June 1. As a response to the earlier arrests, the march took on importance. Says Pat Bryant, "We had to press forward because we had some folks down there who were intimidated by the arrests. We had to organize this march quickly and make it bigger and more historic to show them that we have right on our side and the cops, who they have feared all their lives, don't have the power to stop a legal freedom of expression."

The idea for the march quickly took shape. It would begin at the point of the earlier arrests and include a walk across the Hale Boggs Bridge, the newest span across the Mississippi River, upriver from New Orleans. This time, the parish sheriff's office promised protection and no more arrests. But soon there was a new obstacle: a state transportation official who said they couldn't cross the bridge because of federal laws forbidding pedestrian activity on any part of the interstate system — the bridge is the only completed portion of new spur I-310. The state said it risked millions in federal highway funds, even though the bridge isn't yet connected to the interstate system.

Thursday, with the march two days away, Clare Jupiter sued for a federal injunction to stop the state from denying access, alleging a denial of freedom of expression. On Friday a compromise was arranged, and Saturday morning saw about a hundred activists, with state police escorts, make the five-and-a-half mile walk from Hahnville to the Destrehan Plantation.

"It was beautiful," says Patricia Batiste. "We feel like we made history. We have won a victory they will never forget."

Rose Mary Smith agrees: "That is what we wanted in Marrero and by hard work and determination we got it," she says. "We will prevail in St. Charles Parish and eventually in every project along the Gulf Coast because we have right and we have God on our side."

Tags

Richard Boyd

Richard Boyd is a staff writer with the Times-Picayune in New Orleans. (1988)