Liberating Our Past

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. XII No. 6, "Liberating Our Past." Find more from that issue here.

“A new synthesis awaits the pen of a historian with another world view, fresher insights, and perhaps a different philosophy of history.”

— C. Vann Woodward, 1971

Regions, like people, undergo constant change, and the most dramatic shifts often lead to alterations in self-understanding. Every time we “start over,” we begin to see and explain ourselves a little differently. In the 15 years between 1954 and 1969, the American South experienced a painful and exhilarating struggle for social liberation that was long overdue. That many-sided movement stimulated a less visible but equally complicated and hopeful struggle to set the region’s history “free at last.” This volume is a progress report on the continuing effort to liberate the Southern past.

The people doing the liberating over the past 15 years span several generations, and even continents. Many have received formidable professional training; others have informed themselves in public libraries. But all — through reading old letters and conversing on front porches — have learned from Southerners whose lives have been distorted or dismissed by earlier historians.

The personal odysseys of these liberator-historians differ widely, but as the answers to our recent survey indicate (see pages most credit the Freedom Movement with shaping or crystallizing their commitment to explore a pluralistic, often contentious, always changing South. It’s no accident that such pioneers of this non-elitist perspective as C. Vann Woodward and John Hope Franklin joined a delegation of scholars in the Selma-to-Montgomery March of 1965, nor that many of the writers in this volume participated in one aspect or another of the movement. For just as the Freedom Movement challenged the moral authority of the Southern establishment, so too it called into question scholarly research and popular images of a Southern past that considered no one but white elite males as worthy of attention. And just as the movement inspired individual courage and fostered an environ- ment in which people found themselves taking actions they never dreamed possible, so too a new spirit of experimentation and eagerness prompted a generation of historians to document the roots of a dynamic, activist South — one propelled as much by the revolts and daily struggles of common people as by the economic or egotistical motives of the elite.

With varying degrees of subtlety, the old view projected a harmonious, hierarchical society in which most people found their place according to their color, gender, or class, and kept their mouths shut. “An old fashioned Southern plantation,” wrote Charles Morris, “was one of the purest, sweetest, and most agreeable types of social life ever known.” According to Morris’s 1907 book The Old South and the New, “The black man alone may thank the institution of slavery. Through it, he passed perhaps along the easiest road that any slave people ever passed from savagery to civilization. . . .”

On the other hand, Morris continued, “poor whites . . . largely devoid of education, formed the most undesirable part of the population, many of them living in a state of vice and degradation.” As for the proper place of women: “. . . the mistress of the Southern plantation and through emulation, Southern women generally, was exalted as in no society in the world.”

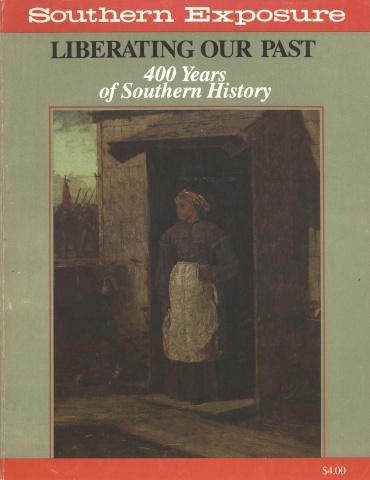

Like Winslow Homer’s painting on the cover, the essays in this book adopt a radically different vantage point toward our collective heritage. People long considered non-actors on the basis of race, class, or sex move to center stage; and the authors who bring them to life have a keen awareness of the often unpredictable relation between past and present.

“Like all historians, I look at the past from a perspective that flows from my personal experience,” writes Jacquelyn Dowd Hall (whose preliminary work for a special edition of Radical History Review formed the core of this collection*). Hall expresses well the interaction of the activist scholar with her subject in the preface to her book Revolt Against Chivalry: Jessie Daniel Ames and the Women’s Campaign Against Lynching:

Certainly, my interest in the movements for racial and sexual equality was enhanced by the ways my own life has been touched and changed by those struggles. I was not drawn to the anti-lynching reformers of the 1930s, however, in a search for political antecedents or exemplary heroines. On the contrary, at the outset the preoccupations of these women seemed quite alien to my own way of viewing the world. Yet in the mysterious alchemy of author and subject, I found myself confronting women who were indeed my forebears.

This book is designed to help more of us confront our forebears. The synthesis C. Vann Woodward hoped for in the early ’70s remains elusive; but the plethora of research from the last decade alone, as represented by the sample bibliographies scattered herein, is truly impressive.

Like many of the works listed, the pieces in this volume are generally more descriptive than analytical or theoretical. Several articles, for example, point to the widespread use of vigilante violence in the region; the far-reaching consequence of this practice for the development of a relatively weak, race-oriented infrastructure of voluntary associations in the working-class South remains to be fully analyzed. Jeffrey Gould’s study of how class and race intertwined in late nineteenth-century Louisiana is a step in this direction.

Similarly, while several articles here reflect our richer understanding of the lives of Southern women, black and white, they only begin the more difficult analysis needed for a feminist theory and practice that unites women from diverse cultural and racial backgrounds. Other essays here illustrate the blend of traditional scholarship with new documentary sources and research methods, including oral history, which students today can carry even further. Indeed, we offer a sampling of the research topics and interdisciplinary approaches that intrigue present historians but which may require a future generation to pursue.

Previous Southern Exposure articles and special editions have drawn on what’s new in the study of our past. We invite you to review the list on pages 108-09 and the inside back cover to add issues that are still in print to your library. This volume is offered as a further testament to the diversity and tenacity of human struggle in this region for more than 400 years, and as a challenge to others to carry on the task of liberating our past. It comes with an invocation that one of our historians has derived from Mother Jones and inscribed above his desk: “PRAY FOR THE LIVING, AND FIGHT LIKE HELL FOR THE DEAD.”

* The seed for “Liberating Our Past” was a planned special issue of Radical History Review on Southern history. That issue was cancelled for financial reasons, but we give thanks to the editors on that project — Leon Fink, Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, Robert Korstad, James Leloudis, Sue Levine and Harry Watson — for allowing us to take up where they left off.