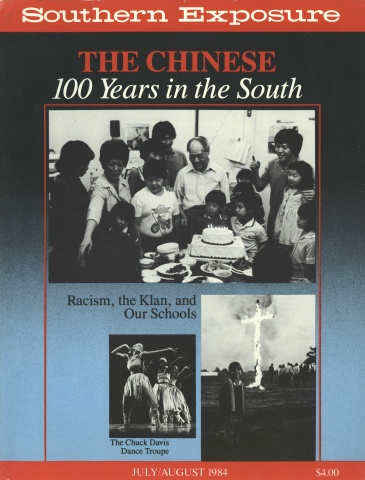

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 12 No. 4, "The Chinese: 100 Years in the South." Find more from that issue here.

In this special section, Southern Exposure explores the history and the presence of Chinese in the South. While growing numbers of Asian people are currently migrating to the region, Chinese have lived here in small numbers for more than 100 years. They are the descendants of laborers originally recruited after the Civil War by unreconstructed Confederates and capitalist speculators seeking cheap labor to work on their railroads and plantations after chattel slavery was outlawed. In this practice, the recruiters imitated Europeans who, throughout their colonies, used East Indian and Chinese labor.

The descendants of the early Chinese settlers are scattered throughout the South, where they occupy an uneasy position between black and white. Although both Chinese and African-Americans have faced oppression, discrimination, and disenfranchisement, they have remained estranged — sometimes even when they share a common ancestor — and they have failed to unite to pursue common political and economic goals. Their common legacy as exploited laborers in this country and as colonized people in their ancestral homelands has been insufficient impetus to overcome the “divide and conquer” tactics of the dominant culture.

The overwhelming impact of the laws defining race and regulating race relations in the South have led to a common perception of the region as biracial. The perception has most recently been reinforced by the dramatic events surrounding the Southern Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ’60s and the rise of black consciousness which followed. The repressive laws and customs which these twentieth-century movements seek to overturn were originally designed to support the doctrine of white male supremacy which provided the foundation for the South’s plantation economy.

To retrieve the hidden history of the nineteenth-century Chinese immigrants to the Southern United States, Lucy M. Cohen conducted an exhaustive search of missionary records, newspaper accounts, census and ships’ logs, and plantation and commercial association records. We have excerpted here from her new book, Chinese in the Post-Civil War South: A People Without a History, to provide information on the background and consequences of the Southern movement to replace black with so-called “coolie” labor after the Civil War. Cohen, who focuses on Louisiana, also interviewed descendants of nineteenth-century Chinese immigrants who still reside in Natchitoches to trace the role that “race” has played in the disappearance of this group of Chinese from public record.

Using a different approach, Third World Newsreel, with a philosophy of filmmaking as political action, trained its cameras on another group of Chinese settlers in the South. Their pioneer documentary effort, Mississippi Triangle, filmed in the Mississippi Delta by a tri-racial crew, explores the complex relationship that evolved among Chinese and African-Americans and whites. Adria Bernardi, who was present at the film’s premiere in Clarksdale, Mississippi, recorded the reactions of some of the Chinese viewers who had also appeared in the film.

While it is clear that the racist practices spawned during the plantation era are still active in the continued political and economic subordination of African-Americans, their impact on other people of color in the South is less visible. Yet a true picture of race relations, and more importantly, a blueprint for progressive change cannot be developed without expanding our understanding of the roots of racial oppression and the impact of racism on all people.